Magdalena River turtle

| Magdalena River turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| From Medellin, Colombia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Pleurodira |

| Family: | Podocnemididae |

| Genus: | Podocnemis |

| Species: | P. lewyana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Podocnemis lewyana Duméril, 1852

| |

| |

| Range in red | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Podocnemis coutinhii Göldi, 1886 | |

The Magdalena River turtle or Rio Magdalena river turtle (Podocnemis lewyana) is a species of turtle in the family Podocnemididae,[3] which diverged from other turtles in the Cretaceous Period, 100 million years ago.[4] It is endemic to northern Colombia, where its home range consists of the Sinú, San Jorge, Cauca, and Magdalena river basins.[5]

The species has been classified as "Critically Endangered" by the IUCN in 2015 and is considered the most threatened species of the family Podocnemididae.[6][7] In less than 25 years, the species exhibited a population decline of over 80%.[4] The decline is attributed to habitat destruction, pollution, over-harvest, commercial exploitation, hydrological changes due to electrical generation facilities, and climate change.[5] While early conservation attempts were unsuccessful or unenforced, there has been a resurgence in studies aimed at discovering the most effective approaches.[8]

Description[edit]

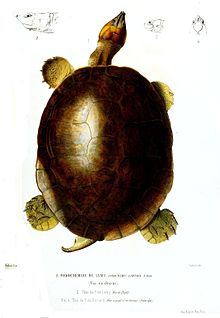

Magdalena River turtles exhibit sexual dimorphism.[9] Both males and females have a shell composed of shield-like plates that are primarily brown in color.[4] Their necks extend to a robust head.[4]

Males have grayish-brown head scales, while females display head scales more reddish-brown in color.[9] Adult males, on average, weigh 1.6 kg and measure 24.6 cm in carapace length.[6] Whereas females, on average, weigh 5.6 kg and measure 37 cm in carapace length.[6]

The species is regarded as having a mostly herbivorous diet, however opportunistic insectivorous behavior has been observed.[9] At times, juveniles pursue piscivorous behavior.[9] Average life span is 10–15 years in the wild.[6]

Ecology[edit]

Reproduction[edit]

Magdalena River turtles are iteroparous.[5] Males sexually mature at 3–4 years old, while females mature at 5–6 years old.[6] Females nest in the sandy riverbanks that result from areas of shallow water.[8]

There are two nesting seasons: December–January and June–July.[8] It is unclear if individual females nest during both seasons in the same year.[4] Higher egg counts are observed in the June–July nesting season.[8]

While average egg weight is significantly greater in the December–January nesting season.[8] Therefore, researchers have proposed it is equally vital to protect both seasons, as egg weight is positively correlated to hatching weight.[8]

Average clutch size is 22 eggs.[4] The embryos within the eggs have temperature-dependent sex determination.[10] The species' pivotal temperature (Tpiv), incubation temperature that produces 1:1 sex ratio, is 33.4 °C.[10] Incubation temperatures below the pivotal temperature produce a greater percentage of male hatchlings, while temperatures above produce a greater percentage of female hatchlings.[10] Concerns have been raised about the effects of climate change on this evolved developmental strategy.[10]

Movement[edit]

Among freshwater turtles, podocnemidids have among the longest aquatic migratory patterns, rarely leaving the water except to bask.[7] Their average home range spans between 10.3 and 14.6 ha.[6] Movement patterns are predicated on sex, body size, food availability, habitat quality, season, reproductive status, and life stage.[7]

Seasonal movements are most prominent due to changing water levels.[7] Research has shown increased movement to deeper waters, likely as a result of climate change.[10]

Conservation[edit]

Threats[edit]

As of 2018, 37% of all freshwater and terrestrial turtle species found in Colombia were classified as "Threatened".[11] Despite legislation passed in 1964 aimed at protecting these species (Ministry of Agriculture Resolution No. 0214-1964), their populations have continually decreased.[11] While many anthropogenic factors have contributed to the decline of Magdalena River turtles, over-harvest and climate change are the most prominent.[5] Over-harvest results from human demand for Magdalena River turtle consumption.[4]

Locals believe that feeding on the turtles offer many medicinal qualities.[4] These include easing pregnancy recovery, curing diseases, boosting strength and longevity, and creating natural aphrodisiacs.[4] Climate change has led to discernible changes in temperature-dependent sex determination and movement patterns.[10][7] It has also contributed to nesting site flooding and other habitat alterations.[7]

While anthropogenic causes are most pronounced, several life history factors contribute to the Magdalena River turtles endangerment, as well.[5] High rates of mortality are seen in eggs, hatchlings, and juveniles.[5] Despite their high rates of survival as subadults and adults, their slow, r-selected growth means it takes a while for those stages to be reached.[5] They also require multiple habitats, one for nesting and another for feeding, which result in strenuous migrations.[5]

Conservation approaches[edit]

The most commonly used conservation approach for Magdalena River turtle conservation is "head-starting".[4] However, research efforts have been focused on finding more effective means on conservation, as understanding of the turtles' endangered nature is relatively novel.[11][6] A study that compiled 16 ecological knowledge criteria of Colombian freshwater and tortoise species suggested that the Magdalena River turtle should receive top conservation priority.[12] Studies are applying faster demographic modeling and surveying to better understand the species and establish practical conservation efforts.[5][11] Faster demographic modeling of the species' vital rates is focused on analyzing the contributions of each life stage and intrinsic growth rates (r).[5] Surveying has shown that local Magdalena River turtle consumption habits have changed and knowledge of their ecological role has improved.[11] This suggests that community-based strategies, including distribution of educational material, is proving effective in the conservation effort of Magdalena River turtles.[11]

References[edit]

- ^ Páez, V.; Gallego-Garcia, N.; Restrepo, A. (2016). "Podocnemis lewyana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T17823A1528580. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T17823A1528580.en. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Podocnemis lewyana, Reptile Database

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Magdalena River Turtle | Podocnemis lewyana". EDGE of Existence. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Paez, VP; Bock, BC; Espinal-Garcia, PA; Rendon-Valencia, BH; Alzate-Estrada, D; Cartagena-Otalvaro, VM; Heppell, SS (2015). "Life History and Demographic Characteristics of the Magdalena River Turtle ( Podocnemis lewyana): Implications for Management". Copeia. 103 (4): 1058–1074. doi:10.1643/CE-14-191. S2CID 86119167.

- ^ a b c d e f g Páez, Vivian; Restrepo, Adriana; Gallego-Garcia, Natalia (2015-07-01). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Magdalena River Turtle". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Alzate-Estrada, Diego A.; Páez, Vivian P.; Cartagena-Otálvaro, Viviana M.; Bock, Brian C. (2020). "Linear Home Range and Seasonal Movements of Podocnemis lewyana in the Magdalena River, Colombia". Copeia. 108 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1643/CE-19-234. S2CID 213305810.

- ^ a b c d e f Ceballos, Claudia P.; Romero, Isabel; Gómez-Saldarriaga, Catalina; Miranda, Karla (2014). "REPRODUCTION AND CONSERVATION OF THE MAGDALENA RIVER TURTLE (Podocnemis lewyana) IN THE CLAROCOCORNÁ SUR RIVER, COLOMBIA". Acta Biológica Colombiana. 19 (3): 393–400. doi:10.15446/abc.v19n3.41366. hdl:10495/11230.

- ^ a b c d Paez, VP; Restrepo, A; Vargas-Ramirez, M; Bock, BC (2009). "Podocnemis lewyana Dumeril 1852- Magdalena River Turtle". Chelonian Research Monographs. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Gallego-García, Natalia; Páez, Vivian P. (2016). "Geographic Variation in Sex Determination Patterns in the River Turtle Podocnemis lewyana: Implications for Global Warming". Journal of Herpetology. 50 (2): 256–262. doi:10.1670/14-139. S2CID 88271464.

- ^ a b c d e f Vallejo-Betancur, Margarita M.; Páez, Vivian P.; Quan-Young, Lizette I. (2018). "Analysis of People's Perceptions of Turtle Conservation Effectiveness for the Magdalena River Turtle Podocnemis lewyana and the Colombian Slider Trachemys callirostris in Northern Colombia: An Ethnozoological Approach". Tropical Conservation Science. 11: 194008291877906. doi:10.1177/1940082918779069.

- ^ Forero-Medina, German; Páez, Vivian P.; Garcés-Restrepo, Mario F.; Carr, John L.; Giraldo, Alan; Vargas-Ramírez, Mario (2016). "Research and Conservation Priorities for Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles of Colombia". Tropical Conservation Science. 9 (4). doi:10.1177/1940082916673708.