Lèse-nation

Lèse-nation, also lèze-nation, was a crime defined in France in connection with the French Revolution. It means an offence or defamation against the dignity of the nation. Both, the name as well as the corresponding law regarding the crime of lèse-nation, go back to the law relating to the crime of lèse-majesté. Both were adapted by the revolutionaries during the French Revolution, so that the focus was no longer on the monarch but on the nation. The English name for lèse-majesté is a modernised borrowing from the medieval French, where the phrase means a crime against The Crown. In classical Latin laesa māiestās means hurt or violated majesty. In the context of the name lèse-nation, it means a crime against the nation.[1]

The law regarding the crime of lèse-nation was in force between 1789 and 1791. It was immediately after the proclamation of the sovereignty of the nation, in the aftermath of the Tennis Court Oath from 20 June 1789, that the foundation for the law regarding the crime of lèse-nation was laid. On 23 June 1789, the National Assembly announced that it will prosecute as criminals all those who, individuals or bodies, attack its existence or the freedom of its members.[2]

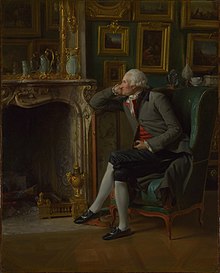

Almost over night, a new crime was invented. Or as Charles-Élie, Marquis de Ferrières, put it: "We suddenly saw the appearance of a new crime unknown to our fathers, a crime of lèse-nation." [3]

The events surrounding the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789 played an important role in the development and implementation of the law. Since the Storming of the Bastille, many denunciations, and the ghost of the complot, obliged the National Assembly to face the problem of the political incrimination. Quick action was required.[4]

Protection for the Revolution[edit]

The law regarding the crime of lèse-nation was introduced in the early days of the French Revolution. It came into force on 23 July 1789 by decree of the National Assembly. It describes intentions that harm the nation and was modelled on the traditional crime of lèse-majesté as if to better illustrate the transfer of sovereignty. The law was introduced to protect the Revolution and its values. It also defined what the nation is. By taking into account the emerging regime's increasing fears of a counter-revolution, it became one of the most important legal measures at the beginning of the Revolution. In the long term, however, not. The weak judicial effectiveness of the law regarding the crime of lèse-nation contrasted with its political ambition. It explains its brief existence since, from 1791, the term crime contre la chose publique (crime against public affairs) was preferred, a criterion of all political justice.[1]

What is a crime of lèse-nation?[edit]

A crime of lèse-nation is to disregard, by will and by fact, the inviolable rights of the nation. Or in short, according to the revolutionaries: The criminals of lèse-nation are those who want to maintain the old despotism and aristocracy. And Maximilien Robespierre reminded his fellow revolutionaries in a speech on 25 October 1790 when it came to introducing new laws and establishing the judiciary: "The tribunal that you have formed must be endowed with courage and armed force, since it will have to fight the great ones, who are enemies of the people." [5][6]

It was defined that crimes of lèse-nation are attacks committed directly against the rights of society. There are two types: those who attack the nation's physical existence, and those who seek to vitiate its moral existence. The latter are as guilty as the first. Crimes of lèse-nation are rare when the constitution of the state is strengthened and the government established, that is, if the government is able to enforce the state's monopoly on the use of force. At this point, however, the young nation was still in the process to form up. Under the constitution of 1791, the crime had to be judged by the Haute Cour Nationale.[7][8]

The who's who of the Ancien Régime in the dock[edit]

The most prominent personalities who were accused of the crime of lèse-nation were: Charles Eugene, Prince of Lambesc, Charles Marie Auguste Joseph de Beaumont, Comte d'Autichamp, Victor François, Duc de Broglie, Charles Louis François de Paule de Barentin and Louis Pierre de Chastenet de Puységur. The only death sentence passed under this law was that of Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras. The Marquis de Favras was sentenced to death on 18 February 1790. The next day, he was hanged on the Place de Grève in Paris. The execution of this judgment is regarded as the first experience of political justice of the French Revolution.[2]

A Swiss baron in the dock[edit]

However, the most famous person accused of the crime of lèse-nation was Pierre Victor, Baron de Besenval de Brunstatt, a Swiss military officer in French service. His case became exemplary. Not only because he was a foreigner, a close friend of Queen Marie Antoinette, and one of the first accused of the crime of lèse-nation, but also because of his fame and his famous friends who campaigned for his release, such as the Marquis de Lafayette, Jacques Necker and the Comte de Mirabeau. What was ultimately important for the baron's survival: These gentlemen also enjoyed respect among the revolutionaries. Furthermore, the baron was represented in court by the best and most prominent French lawyer at the time, Raymond Desèze, who later also defended King Louis XVI in court. The court was deeply impressed by Desèze's plaidoyer. The plaidoyer was even published and was considered a reference in court cases regarding the crime of lèse-nation.[9][10][11][12][13][14]

On Monday, 1 March 1790, the Baron de Besenval was acquitted in the crime of lèse-nation. A verdict that was not without controversy. Quite a few saw this judgment as a courtesy judgment for the baron's influental friends.[10][15]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Sciences Po – Les Presses: Jean-Christophe Gaven, Le crime de lèse-nation – Histoire d'une invention juridique et politique (1789-1791), en ligne, consulté le 30 janvier 2024

- ^ a b Ugo Bellagamba: Jean-Christophe Gaven, Le Crime de lèse-nation. Histoire d'une invention juridique et politique (1789–1791), Criminocorpus, Comptes rendus, mis en ligne le 13 février 2018, consulté le 30 janvier 2024

- ^ Collection des Mémoires relatifs à la Révolution française – Charles-Élie de Ferrières: Mémoires du Marquis de Ferrières – avec une notice sur sa vie, des notes et des éclaircissements historiques par MM. Berville et Barrière, tome premier, livre III, Baudouin Frères, Imprimeur – Libraire, rue de Vaugirard, 36, Paris, 1821, p. 166

- ^ Jean-Christophe Gaven: Le Crime de lèse-nation. Histoire d'une invention juridique et politique (1789–1791), Association des Professeurs d'Histoire et de Géographie (APHG), compte-rendu de lecture / Révolution française, dimanche 14 mai 2017, en ligne, consulté le 30 janvier 2024

- ^ L'Assemblée du District des Cordeliers: Extrait des registres des Délibérations de l'Assemblée du District des Cordeliers, 20 avril 1790, de l'imprimerie de Momoro, Paris, 1790, pp. 12–13

- ^ Maximilien Robespierre: Opinion à la séance du 25 octobre 1790, Moniteur, op. cit. (7), t. VI, p. 211

- ^ Roberto Martucci: Qu'est-ce que la lèse-nation ? A propos du problème de l'infraction politique sous la constituante (1789–1791), Déviance et Société, Vol. 14, numéro 4, 2018, p. 390

- ^ Dictionnaire de L'Académie française: Crime de lèse-nation, 5ème édition, en ligne, consulté le 30 janvier 2024

- ^ Raymond Desèze: Plaidoyer prononcé à l'audience du Châtelet de Paris, tous les services assemblés, du Lundi 1er mars 1790, par M. Desèze, avocat au Parlement, pour M. Le Baron de Besenval, accusé [accusé du crime de lèse-nation], contre M. Le Procureur du Roi au Châtelet, accusateur, chez Prault, Imprimeur du Roi, Quai des Augustins, Paris, 1790

- ^ a b Journal de Paris: L'affaire de Besenval, Numéro 225, supplément au Journal de Paris, Vendredi, 13 août 1790, de la Lune le 4, de l'imprimerie de Quillau, rue Plâtrière, 11, Paris, supplément (no. 59)

- ^ Journal de Paris: L'affaire de Besenval, Numéro 343, Mercredi, 9 décembre 1789, de la Lune 23, de l'imprimerie de Quillau, rue Plâtrière, 11, Paris, p. 1607

- ^ Jean-Philippe-Gui Le Gentil, Marquis de Paroy (1750–1824): Mémoires du Comte de Paroy – Souvenirs d'un défenseur de la Famille Royale pendant la Révolution (1789–1797), publiés par Étienne Charavay, Archiviste Paléographe, Librairie Plon, E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie, Imprimeurs-Éditeurs, 10, rue Garancière, Paris, 1895, pp. 74–75

- ^ Journal de Paris: Jeudi, 30 juillet 1789: M. Necker à l'Hôtel de Ville de Paris – Discours en faveur de M. de Besenval, Numéro 212, Vendredi, 31 juillet 1789, de la Lune le 10, de l'imprimerie de Quillau, rue du Fouare, 3, Paris, p. 952

- ^ François-René de Chateaubriand: Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe, tome premier, Nouvelle édition avec une introduction, des notes et des appendices par Edmond Biré (1829–1907), Garniers Frères, libraires-éditeurs, 6, rue des Saints-Pères, Paris, 1849, p. 302

- ^ Pierre Victor, Baron de Besenval: Mémoires de M. Le Baron de Besenval, imprimerie de Jeunehomme, rue de Sorbonne no. 4, Paris, 1805 – chez F. Buisson, libraire, rue Hautefeuille no. 31, Paris, tome III, p. 434

Further reading[edit]

in alphabetical order

- Jean-Christophe Gaven: Le crime de lèse-nation – Histoire d'une invention juridique et politique (1789-1791), Sciences Po – Les Presses, Paris, 2016

- Roberto Martucci: Qu'est-ce que la lèse-nation ? A propos du problème de l'infraction politique sous la constituante (1789–1791), Déviance et Société, Vol. 14, numéro 4, 2018, pp. 377–393