John Lyons (Louisiana)

John Lyons (b. c. 1822 – September 23, 1864) was a carpenter, bridge builder, cotton-plantation owner, and steamship captain of Louisiana, United States.[1] Lyons is best known today as the enslaver of Peter of the scourged back, who escaped to Union lines in 1863,[2] and whose whip-scarred body ultimately became a representative of the physical violence inherent to the American slavery system.[1]

According to one account of inland Louisiana in the American Civil War, Capt. Lyons was involved in cotton smuggling at the behest of Confederate general Dick Taylor, son of former U.S. President Zachary Taylor.[3] Lyons was shot and killed in his home during a raid by a U.S. military detachment into the Atchafalaya River basin in autumn of 1864; he was apparently personally targeted by someone in the squad named Watson with whom he had an existing conflict.[4][5]

Capt. John Lyons appears as a character in the 2022 film Emancipation directed by Antoine Fuqua and starring Will Smith.[6]

Background[edit]

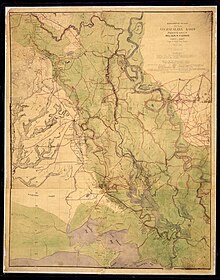

Capt. John Lyons lived in a section of Louisiana that in his time was considered a part of Acadiana and by the end of the 19th century would come to be known as Cajun country. The region, originally home to the Appalousa and Atakapa people, was first colonized by the French and Spanish, and later became part of the United States through the Louisiana Purchase. The Opelousas and Attakapas districts of Orleans Territory and later the U.S. state of Louisiana were polyglot places, with as many French as English speakers, along with indigenous languages, and perhaps Spanish, as regional minority languages. The region was a patchwork of cypress swamps, palmetto swamps, old-growth forest, and wet prairie, interspersed with countless bayous, tributaries and distributaries of the Mississippi River watershed, watercourses that ebbed and flowed seasonally, opening and closing passageways in and out of the region. In the early 19th century the region had a very meager network of surface roads, trails, bridges, and ferries; the New Orleans, Opelousas and Great Western Railroad was organized in the decade prior to the American Civil War.[7]

During the first 60 years of the American era, the major commercial products of the region were cotton, sugarcane, and cattle (which grazed the region's natural grasslands), along with smaller-scale production of timber, corn, and market vegetables. Rice came later. Cotton and sugarcane were cultivated by enslaved laborers on plantations.[7]

Life and work[edit]

Lyons was an emigrant from Ireland to the United States, born in County Leitrim about 1821 or 1822.[8][9] Lyons was 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m), with a ruddy complexion, black hair, and gray eyes.[8] He may have emigrated with a larger family group or traveled to meet relatives who had departed earlier, as the 1840 census of St. Landry Parish (which only recorded names of heads of households, usually male) includes several Lyons, including Gabriel Lyons, Gabriel Lyons fils, Crawfor Lyons, Jacob Lyons, William Lyons, and John Lyons.[10]

In 1842 Lyons enlisted at Albany and signed up for a multi-year enlistment as a private in a U.S. Army artillery unit; he is believed to have participated in the Mexican-American War.[8] On October 30, 1845, he married at Opelousas, Louisiana, to Brigit Delia Fahey.[11] He was discharged from service on July 20, 1847, at Saltillo, Mexico.[8]

At the time of the 1850 census Lyons lived in Saint Landry Parish with his wife and three daughters, aged four, three, and six months old.[9] His occupation was listed as carpenter, and he owned real estate worth US$1,000 (equivalent to $36,624 in 2023).[9] The 1850 slave schedules for Saint Landry Parish listed a slave owner named John Lyons who owned eight slaves, ranging in age from 10 to 50 years old.[12]

In 1853 a John Lyons Sr. of Roberts Cove, Parish of Saint Landry, died and the residue of his estate, including 53 slaves, six creole horses, and about 1400 head of cattle, was auctioned off.[13] In 1854 John Lyons won the contract to build the Waxia drawbridge over the Courtableau. His work was admired:[14]

An appropriation of $4000 was made by our Police Jury some six months ago for the construction of a draw bridge over the Courtableau. The other day, as we were passing by, Mr. John Lyons, the undertaker, invited us to come and witness the working of this bridge, which is now ready to be delivered; and we must acknowledge that we were surprised to see such a heavy mass of timber moved by one man, and that too without any difficulty. The plan is a new one in our Parish and it is said to be the only one known in the State. ¶ The opening is 566 ft (173 m) wide, and a length of 130 ft (40 m), is made to turn on a pivot by a single man. It is a strong, and beautiful construction, which would be too tedious to detail here, by one who is not acquainted with the art. Be it said, en passant, that this bridge is the best of all in the parishes of St. Landry and Attakapas, and that the constructor has had but his due when one of our friends, after examining it, said that our friend John, was the Lion of all the bridge builders.

— Opelousas Courier, Feb. 18, 1854, page 2

In 1855, Lyons was administrator of the estate of a neighbor named David Hudspeth, whose plantation was along Bayou Beouf.[15]

Sometime in the late 1840s or 1850s, Lyons began commanding river steamboats that traveled the waterways of west-central Louisiana between inland ports, from Washington, Louisiana, down to New Orleans. As one 1891 history of the region explained, "St. Landry is well watered and drained by its numerous streams and bayous. The Atchafalaya River, which borders its eastern limit, connects the parish by steamboat with the Mississippi River and New Orleans. The Bayou Courtableau, formed by the junction of the Crocodile [recte Bayou Cocodrie] and Beouf, affords good navigation to Washington the entire year, except a short period in summer when there is usually extreme low water. The Bayou Boeuf is the means of transportation for the planter, and the Crocodile for the lumber men."[7] Washington, sometimes called Washington Landing, is located about 6 mi (9.7 km) north of the parish seat of Opelousas, and had developed into a thriving trading center and inland port in the years before the civil war.[16] According to a 1974 journal of the Louisiana Historical Association account of 19th-century water transportation in Louisiana, "Washington, Louisiana to New Orleans was a distance of about 340 mi (550 km), which took 35 or 40 hours by water."[16]

Lyons had command of a steamship called the Mary Bess in early 1856, between Washington and New Orleans.[17][18][19] At one point she ran late because she was stranded on an Old River sandbar.[20] In partnership with J.B.A. Fontenot, Lyons established a freight warehouse at Washington Landing in 1856.[21] In March of that year, Lyons was compelled to place a notice in the newspapers "TO THE PUBLIC IN GENERAL...There is a report circulating through the country and New-Orleans, that the steamer Mary Bess is an unsafe boat, and that there is no insurance on her. I deem it my duty to contradict all such reports, and tax the man or men who have circulated them as infamous liars. Come and see our papers of insurance at Washington, La. 2d. February, 1856."[22] In June 1856 the Mary Bess was one of five steamboats that burned at the Algiers landing in New Orleans. The commander of the Mary Bess, one Capt. Holmes, was believed to have been killed in the fire.[23] The New Orleans Picayune-News was unable to determine if the Mary Bess was insured; she was valued at US$10,000 (equivalent to $339,111 in 2023).[23]

In October 1856 a New Orleans newspaper published advertisements for the trips to Opelousas via the steamer Union, commanded by John Lyons, that promised the steamer would make the journey "through in twenty-four hours...taking freight for Lower Atchafalaya, Lake Chicot, and Butte a la Rose."[24] In 1857 the government of St. Landry Parish determined to pay John Lyons US$100 (equivalent to $3,270 in 2023) to repair the bridges over Bayou Carron and Bayou Toulouse.[25] In 1858, Lyons' Bayou Belle would "leave Washington for and all intermediate landings, every Wednesday at 10 o'clock, A.M. and New-Orleans every Saturday at 5 P.M. The Bayou Belle being of very light draught and well calculated for the trade, planters and shippers can rely on her remaining in the trade, and running in all stages of water."[26][27] In March 1859 the The New Orleans Crescent reported that the Bayou Belle had arrived in town bearing "with 59 bales cotton, 29 hhds. sugar and 36 bbls. and 133 bbls. molasses, and leaves again this evening."[28]

At the time of the 1860 census, Lyons lived in Saint Landry Parish, with his wife, four daughters and son. His occupation was planter, he owned real estate worth US$20,000 (equivalent to $678,222 in 2023), and his personal estate was worth US$42,000 (equivalent to $1,424,267 in 2023).[29] The 1860 slaves schedules for Louisiana record that John Lyons owned 38 people, the oldest being a 60-year-old man, the youngest being a one-year-old girl.[30] Also in 1860, Lyons' brother-in-law John Fahey lived in Grand Coteau, Louisiana, five houses down the road from A.P. Carriere, more properly, Pierre Arthéon Carrière, a 30-year-old clerk with three children and total property valued at $500.[31][a] "Artayon Carrier" may be an Anglophone's phonetic spelling of Arthéon Carrière, as the letter from "Bostonian" (written November 12, 1863 and published in the New-York Tribune about the Harper's Weekly images and story of "poor Peter") also attests that the name of overseer who whipped Peter was Artayon (not Artayou) Carrier.[32]

American Civil War and death[edit]

In spring 1863, an enslaved man by the name of Peter escaped Confederate-controlled Louisiana and made his way to the U.S. Army, which was operating under General Nathaniel P. Banks' General Order 12, Promulgation of the Emancipation Proclamation: "Officers and soldiers will not encourage or assist slaves to leave their employers, but they cannot compel or authorize their return by force."[33] A photograph of Peter's heavily scarred back and excerpts from his explanation of what had happened to him were widely promulgated to the general public by anti-slavery advocates.[1] Peter was reported to have said, on April 2, 1863:[34]

Ten days from to-day I left the plantation. Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping. I don't remember the whipping. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping and my sense began to come—I was sort of crazy. I tried to shoot everybody. They said so, I did not know. I did not know that I had attempted to shoot everyone; they told me so. I burned up all my clothes; but I don't recall that. I never was this way (crazy) before. I don't know what make me come that way (crazy). My master come after I was whipped; saw me in bed; he discharged the overseer. They told me I attempted to shoot my wife the first one; I did not shoot any one; I did not harm any one. My master's Capt. John Lyon, cotton planter, on Atchafalya, near Washington, Louisiana. Whipped two months before Christmas.[34]

Lyons' wife died on January 2, 1864.[35]

In January or February 1864, a Southern Unionist named Dennis Haynes who was attempting to get out of Louisiana "tried to get on board of a flat-boat to go down the bayou to the Atchafalaya river, but I was informed by a Frenchman, a Union man, that Dick Taylor would allow no cotton to be shipped from there by private individuals; that all the cotton shipped was '[Confederate] government' cotton; that a Captain Lyon was hired by 'Little Dick' to purchase cotton for him, to be delivered at the mouth of the Cortabla, at fifty cents, Confederate money; that 'Little Dick's' brother-in-law was then delivering the cotton to merchants from Illinois, who were paying for it in gold and silver."[3] (The Dick Taylor in this report is most likely Confederate Army general Richard Taylor, the son of former U.S. president Zachary Taylor.) Taylor and his agents, such as Lyons, were trying to defeat the increasingly successful Union blockade of Confederate ports.

Lyons was shot and killed by "Yankee raiders" on September 21, 1864. According to a contemporary account in the Opelousas Courier, "It has been reported here that the federals had crossed three or four hundred men at Morgan's Ferry, on the Atchafalaya, on Wednesday last. The result will probably be that they will soon be driven back on the other side. We regret to have to announce the murder of Capt. John Lyons, at his own house, on the Atchafalaya, on Wednesday last. It would seem that the yankees made a raid at his house, and among the raiders was a man by the name of Watson, who had formerly lived in the neighborhood, and who had a grudge against Lyons. Upon entering the house Watson fired at Lyons and killed him instantly."[36]

A report to Confederate governor of Louisiana Henry Watkins Allen described in detail the presence and actions of the U.S. Army in 1863 and 1864. The account of happenings in St. Landry was provided by Louisiana militia brigadier-general John G. Pratt, and one Col. John E. King. It mentioned the killing of Lyons as part of the wartime circumstances in the region, albeit as a one-off event distinct from the main invasion: "On the 22d of March the rear guard of the 'grand army' passed the northern limits of St. Landry. — Since then, with the exception of occasional visits to the wooded outskirts, from military posts on the Mississippi, by marauders who came to open a ballot box, in which to deposit their own votes; or to capture or marder an unoffending citizen, this district has been free from the tread of the enemy....Recently a raid was made in that part of St. Landry which stretches along the upper Atchafalaya, by a body of federal troops from Morganzia. A party of soldiers from this body, conducted by a soi-disant Union man who had been driven from the country for his crimes, went at midnight to the house of Mr. John Lyons, once well known as a popular and skillful commander of steamboats on the inland waters of this district, then a respectable planter, and calling him out from his bed, cruelly murdered him on the threshold of his own door."[5]

In October 1865 the household goods and livestock of John and Bridget Lyons were put up for auction by the administrator of their estate, a neighbor by the name of Hudspeth.[37] In 1870 property that belonged to the estate was being auctioned off, including the family home in Washington, and a warehouse lot that had once stood near the saw mill and the drawbridge on Bayou Cortebleau.[38]

"The master and the slave were alike happy, in their respective vocations. Such a condition naturally suggests the reflection, that the system which has produced them could only be in harmony with the wise designs of a beneficent Providence."

In popular culture[edit]

Jayson Warner Smith plays Lyons in the 2022 film Emancipation directed by Antoine Fuqua and starring Will Smith.[6]

See also[edit]

- Steamboats of the Mississippi

- History of Louisiana

- Irish Americans in the American Civil War

- History of slavery in Louisiana

- Atchafalaya National Heritage Area

- Bayou Cocodrie National Wildlife Refuge

- Red River campaign

- Siege of Port Hudson

- Contraband (American Civil War)

- Opelousas Massacre

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Abruzzo, Margaret (2011). Polemical Pain: Slavery, Cruelty, and the Rise of Humanitarianism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 200–206. doi:10.1353/book.1859. ISBN 978-0-8018-9852-5. Retrieved 2023-07-25 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ a b Silkenat, David (May 4, 2014). ""A Typical Negro": Gordon, Peter, Vincent Colyer, and the Story behind Slavery's Most Famous Photograph". American Nineteenth Century History. 15 (2): 169–186. doi:10.1080/14664658.2014.939807. hdl:20.500.11820/7a95a81e-909c-4e8f-ace6-82a4098c304a. ISSN 1466-4658. S2CID 143820019.

- ^ a b Haynes, Dennis E. Haynes (1866). A thrilling narrative of the suffering of the Union refugees. Washington: McGill & Witherow. p. 37.

- ^ "John Lyons' murder, Sept. 1864 by Federal soldiers". The Opelousas Courier. September 24, 1864. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ a b c Louisiana; Allen, Henry Watkins (1865). Official report relative to the conduct of federal troops in western Louisiana, during the invasions of 1863 and 1864. Shreveport, La.: News printing establishment—John Dickinson, proprietor. pp. 7, 32 – via Duke University Libraries, HathiTrust.

- ^ a b Grobar, Matt (November 11, 2021). "Antoine Fuqua's Apple Thriller 'Emancipation' Adds Steven Ogg, Grant Harvey, Ronnie Gene Blevins & More". Deadline. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ a b c Perrin, William Henry (1891). Southwest Louisiana, biographical and historical. New Orleans: Gulf Publishing Co. p. 29 – via Library of Congress, HathiTrust.

- ^ a b c d "US Mexican War Search Detail – Palo Alto Battlefield National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ a b c "Entry for John Lyons and Brigett Lyons, 1850", United States Census, 1850

- ^ "Entry for John Lyons, 1840", United States Census, 1840 – via FamilySearch

- ^ "John Lyons and Brigit Delia Fahey, 30 Oct 1845; citing St. Landry, Louisiana, United States, various parish courthouses, Louisiana", Louisiana Parish Marriages, 1837–1957, FHL microfilm 870,694 – via FamilySearch

- ^ "Slave Schedules, 1850", United States Census – via FamilySearch

- ^ "Lyons 1853 Parish of St. Landry". The Opelousas Courier. July 16, 1853. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ "Waxia Bridge". The Opelousas Courier. February 18, 1854. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (January 27, 1855). "The Opelousas courier. [volume] (Opelousas, La.) 1852–1910, January 27, 1855, English, Image 1". ISSN 2332-5364. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ a b Millet, Donald J. (1974). "The Saga of Water Transportation into Southwest Louisiana to 1900". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 15 (4): 339–355. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4231426.

- ^ "Bateaux a Vapeur". The Opelousas Patriot. February 23, 1856. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ "John Lyons, riverboat captain". The Opelousas Patriot. January 26, 1856. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ "New Orleans – Mary Bess – Opelousas". The Times-Picayune. April 15, 1856. p. 8. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ "Steamer Mary Bess". The Opelousas Patriot. February 9, 1856. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ "New Warehouse". The Opelousas Patriot. February 9, 1856. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ "To the public in general". The Opelousas Courier. March 1, 1856. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ a b "The Steamboat Conflagration". The Times-Picayune. June 10, 1856. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ "Opelousas – Steamer Union". The Times-Picayune. October 14, 1856. p. 8. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ "Bridge repair". The Opelousas Patriot. January 10, 1857. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ "New-Orleans and Opelousas Regular Packet". The Opelousas Courier. June 12, 1858. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ "Steamboat". The Opelousas Patriot. August 21, 1858. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ "Arrivals". The New Orleans Crescent. March 9, 1859. p. 7. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ "Entry for John Lyons and Brigite Lyons, 1860", United States Census, 1860 – via FamilySearch

- ^ "Entry for John Lyons, 1860", United States Census (Slave Schedule), 1860 – via FamilySearch

- ^ "Entry for John Fahey and Caroline Fahey, 1860", United States Census, 1860 – via FamilySearch

- ^ "The Realities of Slavery: To the Editor of the N.Y. Tribune". New-York Tribune. December 3, 1863. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ United States; Irwin, Richard Bache; Banks, Nathaniel Prentiss (1863). Promulgating the Emancipation Proclamation. General orders; no. 12.

- ^ a b "Scars of slavery". The National Archives. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ^ "United States Deaths and Burials, 1867–1961", database, FamilySearch https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:HFBN-8F6Z Mrs. John Lyons, 1864.

- ^ "Opelousas, Saturday, September 24, 1864". The Opelousas Courier. September 24, 1864. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ "Succession Sale". The Opelousas Courier. September 30, 1865. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ "Public sale: Estate of John Lyons and wife [Column 6]". The Opelousas journal. Opelousas, La.1868. January 1, 1870. p. 2. ISSN 2377-827X. Retrieved 2023-07-23 – via Chronicling America.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

External links[edit]

- Archived copy of genealogy page: Captain John Lyons of St. Landry Parish

- "Pierre Arthéon Carrière, Male, 1830–1880", FamilySearch.org, G9C9-3DH, retrieved 2023-07-24

- 1820s births

- 1864 deaths

- American cotton plantation owners

- 19th-century American planters

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- Civilians killed in the American Civil War

- Deaths by firearm in Louisiana

- History of slavery in Louisiana

- Irish emigrants to the United States

- People from St. Landry Parish, Louisiana

- People of Louisiana in the American Civil War

- Steamship captains

- American slave owners

- American steamboat people