Félix Milliet

Félix Milliet | |

|---|---|

| Jean Joseph Félix Milliet | |

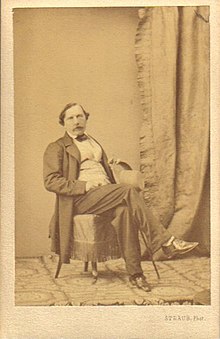

Portrait of Félix Milliet, unknown author | |

| Born | July 19, 1811 |

| Died | October 22, 1888 |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Cavalry School of Saint-Cyr Cavalry School of Saumur |

| Occupation(s) | Officer, annuitant Republican, poet, painter |

| Years active | 1830s to 1860s |

| Notable work | Chansons de Félix Milliet Chansonnier impérial pour l'an de grâce 1853 |

| Style | Political songs |

| Political party | Montagne |

| Movement | Fourierism, republicanism, socialism |

| Spouse | Louise Milliet |

| Children | Alix Payen Paul Milliet |

| Signature | |

Félix Milliet, born on July 19, 1811, in Valence and died on October 22, 1888, in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, was a French officer and then republican activist, poet and chansonnier. He campaigned alongside his wife Louise Milliet, who was born on January 28, 1822, in Le Mans and died on July 10, 1893, in the 5th district of Paris.

An orphan from Drôme, Félix Milliet developed his republican ideas after the July Revolution in 1830. He pursued a military career, which led him to Maine, and practised the art of poetry. There he met Louise de Tucé, a teenager from a wealthy noble family. They married and moved to Le Mans.

It was in Le Mans that Félix Milliet's political career reached its peak. He rubbed shoulders with important republicans in town, such as Auguste Savardan, Marie Pape-Carpantier and Jacques François Barbier. After leaving the army, he became known for his politically committed songs, which he published in newspapers that were regularly banned by the July monarchy and then by the republican regime of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. He described himself as a socialist, although in practice he was very moderate, and shared the anti-clerical and Fourierist ideas of his friends. He supported the Parisian insurrection of the June days in 1848 and then stood in the legislative elections the following year among the candidates of the Montagne.

After the coup of December 2, 1851, he was implicated in an attempted insurrection in the Manche region and condemned to exile in Nice at the beginning of 1852. He took refuge in Geneva, brought his family back to him and continued his commitment. He continued to write and publish songs, until one of them, Chansonnier impérial pour l'an de grâce 1853, led to him being sentenced to exile again, this time to London.

Félix Milliet took refuge in Savoie, which was then attached to the kingdom of Sardinia. He stopped his political publications and devoted himself to painting and his family. Still a Fourierist, he considered joining the Phalansterian project of La Réunion in Texas, before the project collapsed; he saw in these small communities the possibility of a utopian "world harmony". He did not return to France until 1866, seven years after the amnesty law for politically convicted people and fourteen years after the beginning of his exile.

He spent the last twenty years of his life retired in Paris, then at La Colonie, a phalanstery located in Condé-sur-Vesgre (Seine-et-Oise). His wife Louise Milliet took an active part in the organisation of the community, but he was not very active. He died in 1888. He owes his fame in part to his son Paul Milliet, who recounts his life in a family biography published in Charles Péguy's Cahiers de la Quinzaine in 1910.

Family life[edit]

Studies and the beginning of the republican commitment[edit]

Jean Joseph Félix Milliet was born in 1811 in Valence[1] to Élisabeth Vialet and Joseph Milliet, a doctor[2] and landowner[3] from Cluses (Haute-Savoie) who had been living in Valence since the year IX.[2] He was orphaned at the age of nine and his only family was a sister, Célie Milliet, five years older than him,[4][5] and a maternal uncle, an artillery colonel and director of the arms factory in Saint-Étienne, who had retired to the family property in Saint-Flour (on the banks of the Rhône[6] and in the municipality of Guilherand-Granges[6]). He was brought up by family friends and studied at the college of Valence, then at that of Lyon. He obtained his baccalauréat ès lettres on October 16, 1829, at the age of eighteen.[7]

The following year, Félix Milliet went to Paris to study at the Law school. The first performance of Victor Hugo's play Hernani on February 15, 1830, made a political impression on him; he admired Hugo and was enthusiastic about his ideas. However, a republican, he took part in the July Revolution and, according to his son Paul Milliet, more particularly in the "Rambouillet expedition".[7]

Taken by surprise by the political events, he stopped his law studies, in which he had little interest,[7] in order to start a military career. He studied at Saint-Cyr, then at the Cavalry School of Saumur. He became a second lieutenant in the chasseurs à cheval.[1]

Wedding with Louise de Tucé[edit]

Having joined the regiment of the 7th Lancers, Félix Milliet was sent to garrison in Vendôme and Montoire-sur-le-Loir (Loir-et-Cher).[1] It was there that he met Louise de Tucé, a sixteen-year-old girl, in 1838.[7] He wished to marry her, and during that year wrote many poems praising his budding love.[7][alpha 1]

However, her social background blocked their possible union for a time. Louise de Tucé descended from a wealthy family from the provincial nobility of Maine, whereas Félix Milliet had no title of nobility and only a few modest properties. Tucé's mother, Aimée Hüe de Montaigu, did not want her daughter to be married until she was eighteen and to a wealthy, highborn man;[7] so she wrote to Félix Milliet on December 8, 1838, that her "daughter belongs to one of the oldest families in Maine, who would find it inappropriate for me to make Louise form an alliance in which she would find neither birth nor title".[7][8] In spite of this, she took into consideration the love that Félix Milliet had for her daughter. She then demands that he wait, and that he acquires a title of nobility on his marriage. He had the possibility of doing this by adding the name of his property in Saint-Flour to his own. He refused because of his political convictions.[7]

Louise de Tucé and Félix Milliet finally became engaged in January 1839. Their wedding took place three months later,[7] on 13 April in Le Mans;[9] he was twenty-seven years old, she was seventeen.[7]

Family man[edit]

Félix and Louise Milliet had their first child in 1840, on 6 August, named Fernand.[7] He was followed less than two years later by Alix, on May 18, 1842.[10]

When he married, Félix Milliet was in garrison at Vendôme and a second lieutenant in the 8th Lancers.[9] He continued his military career and in the following years became a cavalry officer.[7] With his regiment, he changed garrisons several times, joining Pontivy in Morbihan or Alençon in Orne.[10] However, he suffers from a larynx disease and wishes to be closer to his family and to devote himself fully to poetry. He resigned from the army and joined his wife and children[10] in Le Mans. Their third child, Paul, was born on 6 March 1844, followed by their fourth, Jeanne, in 1848.[1]

Until then, Louise Milliet had been living near her mother Aimée Hüe de Montaigu in Le Mans. When they got back together, the couple moved into a house that they had built, with a courtyard and garden, near her mother's house. They took advantage of a house she had built in Montoire-sur-le-Loir for their holidays.[10]

Félix Milliet regularly writes poems about his life and paintings. He participates in the education of his children.[10] Louise Milliet abandoned her religious practices and became involved in the arts, literature, philosophy and politics. She develops a political thought similar to that of her husband.[10]

Republican activism in Le Mans[edit]

Progressive group of friends[edit]

During the first years of their marriage, the young couple settled in Le Mans, the capital of Sarthe. This was a republican department, which was conducive to his making friends with republican[8] and liberal activists.[10] His circle of friends included the pedagogue and feminist Marie Carpantier, then director of the salle d'asile, an early form of nursery school,[10][11] the writer Louis Clément Silly, the Phalanstrian couple Trahan,[10] the radical publicist Napoléon Gallois,[alpha 2] the republican Édouard Prudhomme de La Boussinière, director of a workers' reading circle, Julien Chassevant,[alpha 3] a fervent follower of Charles Fourier, and Dr. Jacques François Barbier.[alpha 4][8][9][12][13][14][15] With the families of the latter two, the Milliets met regularly at picnics where they developed their republican and Fourierist[15] ideas - the latter being mainly transmitted by Julien Chassevant.

Considering himself "liberated" from the dogmas of religion and under the influence of the theses of Charles Fourier, Félix Milliet was initiated into Freemasonry on May 25, 1846.[alpha 4] He became a speaker[9] at the Manche lodge "des Arts et du Commerce". Dr Barbier joined him a few years later; Paul Milliet described him as his father's "most intimate" friend.[alpha 4]

Activities[edit]

A new revolution broke out in Paris in 1848, the so-called February Revolution, in which King Louis-Philippe I and his regime of the July Monarchy, established after the 1830 Revolution, were overthrown in favour of a Second Republic. Presidential elections on the basis of universal male suffrage were held and Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleon I's nephew, took power.

Under this new Republic under construction, Félix Milliet became a committed republican figure in Le Mans alongside Barbier.[alpha 4][14] They were so-called "advanced" republicans, supporters of the left-wing parliamentary group La Montagne and its leader Alexandre Ledru-Rollin, a candidate in the presidential election. A Republican Central Committee of the Sarthe was founded in 1848, with Barbier as its chairman and Milliet as its secretary.[alpha 4] Milliet was a candidate, along with a man named Silly, in the 1849 legislative elections in Sarthe, where the members of the sole legislature of the National Legislative Assembly of the Second Republic were elected. There were twenty-seven candidates for ten deputies to be elected and 3,118 voters. Milliet obtained 1,113 votes, Silly 1,115,[16] but they withdrew to leave the seat to Ledru-Rollin.[17]

Félix Milliet was particularly active as a songwriter. He had his collections published in Le Mans, where they were successful.[10] Others were published through Bonhomme Manceau, democratic sentinel of Sarthe, Orne and La Mayenne,[alpha 5] a weekly newspaper published from 1849 to 1850 and regularly seized, co-founded by Édouard Prudhomme de La Boussinière and Jean Silly,[alpha 6] and edited by Napoléon Gallois.[alpha 2] He was succeeded in 1851[15] by the more moderate Jacques Bonhomme,[alpha 7][7] within which Félix Milliet, Doctor Barbier and a Silly wrote.[7] Montagnard newspaper, it claimed to denounce the "dynastic and dictatorial pretensions that dared to threaten the Republic"; however, its publication was short-lived, from February to April 1851, and it only had eight issues.[alpha 7] The reason for this was a conviction by the Correctional court in Angers on 29 March 1851. It was then recreated under the name Le Petit Bonhomme manceau.[alpha 8][7]

In his verses, Félix Milliet confirmed his commitment to the Republic[1] and his anti-monarchist, anti-clerical and socialist ideas. During the first months of the Second Republic, he defended the defeated workers of the national workshops,[14] notably through his song Courage and faith, written after the deadly repression of the June Days in 1848 in Paris; a "cry for mercy", in the words of his son Paul.[alpha 9][10] On April 15, 1849, he dedicated one of his texts to one of the most popular songwriters, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, then at the end of his career. Béranger wrote an encouraging letter[18] back[19] to him on 18 April.[20]

Alas! in vain the poor proletarians

From a fatal yoke would like to free themselves,

Capital embraces them in its claws!

Sing again, O Béranger.

The holy war in Europe is getting ready;

Freedom is recruiting its soldiers.

Everywhere the slave has raised his head

And before him the potentates tremble.

Against the kings, at the signal of France,

See, see our brothers rise up!

Sound the hour of deliverance for them,

Sing again, O Beranger.— untitled song by Félix Milliet, 1849

In the preface to a collection published in 1850 by Propagande Démocratique et Sociale, in which Félix Milliet included the letter Béranger had sent him, Napoléon Gallois described his friend's songs as an expression of "hatred of tyranny, pity for those who suffer, aspiration towards a more equitable organisation of society, faith in a future of peace and world harmony".[1][10] In the same year, Félix Milliet published a song, Marchons en frères, with music by P. Garreaud,[21] dedicated to Doctor Auguste Savardan,[1] an important Fourierist from the Sarthe region with whom he was in contact.[alpha 10]

Félix Milliet was also elected captain of the National Guard artillery in Le Mans,[19] which shared his opinions.[10] When a reactionary newspaper published an article insulting the Guard, he challenged its director to a duel and beat him.[22]

Political exile in Savoie[edit]

Direct consequences of December Two[edit]

On December 2, 1851, the President of the Republic Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who was prevented by the constitution from renewing his mandate, proclaimed himself Prince-President in a coup. He established an authoritarian state in which the republicans suffered considerable repression. A year later, he restored the Empire and became Emperor of the French under the name of Napoleon III.

In the days following the coup, Félix Milliet was accused by the Bonapartist forces of having participated in an attempted insurrection which took place in the commune of La Suze.[alpha 11][23] Three hundred workers from a tannery were armed by their boss Ariste Jacques Trouvé-Chauvel, a former republican politician. They took the town hall on 4 December, but the affair was short-lived and they surrendered on the 6th.[24] During the following January, Félix Milliet was the target of a wanted notice published in the press and on posters, which announced : "The government has just given the order to search for and arrest wherever they are found the following persons: [...] Milliet, ex-captain of the national guard, aged 50 [...] Warrants have been issued for these nine persons, who have fled and who are accused of being authors or accomplices of the insurrection which took place in La Suze (Sarthe). His name appears alongside those of Trouvé-Chauvel and his close companions as well as Jean Silly[alpha 5] and Philippe Faure, both members of the Bonhomme Manceau team.[23]

The Sarthe Commission condemned Félix Milliet to expulsion, along with twelve other men judged for the same acts - including Édouard Prudhomme de La Boussinière and Philippe Faure - who were the following: "They have all been affiliated for a long time, as directors or principal agents, with the political society which, under various titles, had given itself the mission of spreading demagogic or socialist principles in the department of La Sarthe; That at all times they were seen drafting or distributing the writings of this society, convening or presiding over its meetings, ensuring the execution of its decisions and, in a word, striving to direct public opinion in the direction of its doctrines, as attested by all the documents seized at the home of Mr Bouteloup. That at the time of the events of December 2, they were at the head of an organization whose goal was to change the form of the Government, except to wait for the time and to seize the pretext which the circumstances would provide, and that during the moment which came, they endeavoured to ensure the execution of the plans by them for a long time meditated; that, disregarding the comings and goings of the first few days as well as the attempt made on the night of December 3 against the town hall of Le Mans, it appears from the investigation that on the 5th, at one o'clock in the afternoon, the above-mentioned assembled at the home of Sieur [Sylvain] Fameau, one of them, whom they designated as president, and that they opened a deliberation; that the object of this deliberation was: Will we take up arms? On what day and at what time shall we do so? That it was resolved to wait until the following day, the 5th, at four o'clock in the afternoon; that the plan was to violently replace all the authorities then in office; to install in their place provisional administrations and thus paralyse all governmental action by the President of the Republic.[23]

Sentence to exile[edit]

On March 27, 1852, Félix Milliet received an exile order from French territory for Nice (then a province of the kingdom of Sardinia).[22] A total of 250 Republicans were arrested in La Sarthe.[1] His close comrades also suffered repression: Auguste Savardan was kept under surveillance at his home,[9] Napoleon Gallois was sought by the police and took refuge in Belgium, Jacques François Barbier, who was present at the famous meeting of the 5th December at Sylvain Fameau's house, fled to the island of Jersey before the end of the judicial investigation;[19] with Félix Milliet, there were nine Freemasons from the "Lodge of Arts and Commerce" who were prosecuted. Only Marie Pape-Carpantier[9] and Julien Chassevant were not seriously concerned.[13]

When he took the road to exile in the direction of Nice, Félix Milliet did not obey and took refuge in Geneva,[19] which he preferred to Nice. He left alone at first, but Louise Milliet joined him later that year. She was in charge of the removal, the sale of the non-moveable goods, the renting of their house and taking the children. She arrived in Geneva at the end of May 1852 with Fernand, aged eleven, Alix, aged ten, and Paul, aged eight; little Jeanne, aged four, was left with her grandmother. Her grandmother was also in charge of managing the affairs of their estate, travelling between Valence and Maine.[22] The couple was very well received in Geneva, where they were received by the Freemasons.[1] Family life was well organised[22] and Félix Milliet resumed publishing his songs.[1]

In Geneva, the case of the Imperial Songwriter[edit]

The publication of a collection of violent songs[22] almost led to Félix Milliet's downfall. Le Chansonnier impérial pour l'an de grâce 1853[25] was published anonymously[22] with the false location "Brussels and London", but was in fact printed in Lausanne.[19] One of its printers wrote to a friend of Félix Milliet: "I hesitated for a few days, because I'll be damned if I'm not going to be hanged if I find out about such strong coffee things. So I beg you not to spread the word and let no one know that this was printed in Switzerland. It must have come from London or New York". But Milliet was not the most cautious and distributed his work around him. He had it printed in small formats, in order to send them in letters, and asked other French refugees to distribute them in Geneva.[25] Thus, his name was quickly known and recognised; the Journal de Genève presented him as a conspirator, an agent provocateur "allied with the French nobility"[22] and the Geneva police minister Abraham Louis Tourte,[26] politically a radical, wrote of him on 9 May 1853 that he was one of the "ultramontanes" who, according to him, were manoeuvring jointly with the Austrian Empire in order to confuse Geneva and France, that he was a "socialist [...] allied with legitimist families! captain of the hussars at 34! brother of the colonel of the 7th Lancers! friend of the count of Arnonville and the marquis Laboussière and whose furious songs were peddled by Lombards now on the run."

As soon as his name became known as the author of the collection, Félix Milliet was arrested by Abraham Louis Tourte[25] and taken to prison. The police seized several papers which they took from his secretary.[22] The authorities wanted to exclude him from Geneva, and why not from Switzerland, but the popular support for him was feared.[25]

Indeed, Milliet was appreciated and had several supporters in the town, notably that of Colonel Alexandre Humbert, who threatened a riot and to go and get his comrade by force; he was in turn arrested and expelled to Bern. Louise Milliet went to Berne to plead her husband's case to the federal authorities. Even Tourte wrote in a report to Federal Councillor Daniel-Henri Druey on 5 May 1853 "Mr. Milliet is recommended by the most honourable citizens. [...] I beg you [...], not to expel him from Switzerland but only to intern him with his family in another canton." then "I have just questioned Mr. Milliet who seems to me a very reasonable man and more imprudent than ill-intentioned. As his children are here at the Collège [de Genève], I beg you [...] to intern him on parole and not to send him away from Switzerland. Removals indignantly upset our population and make it almost impossible to get the refugees to leave for Bern, and it is said that if they knew they were interned, no one would take their side.[25]"

This was not enough to convince the authorities. The Federal Council expelled Félix Milliet[25][27] in May 1853[28] to Antwerp in Belgium, where he embarked for London.[22]

After his departure, Abraham Louis Tourte wrote: "Everyone now agrees with me in the Milliet affair, [...] except however 100 to 150 socialists and a few traitors. [...] There is talk in some quarters of prosecuting me for violating the law on the inviolability of the home, but I will not be intimidated. [...] We [the radicals] will defend ourselves by all means.

Settlement in Sardinia[edit]

However, Félix Milliet did not want to settle in London, and neither did Louise Milliet. She found asylum in Savoie (then a territory under the control of the Kingdom of Sardinia as was Nice) with Dr Pollet, another French exile.[22] Thanks to a fake passport[25] and the help of the Freemasons,[29] Félix Milliet reached Savoy and found his family. This became known in August 1853 in Geneva; Abraham Louis Tourte wrote to Daniel-Henri Druey on 11 August: "It is certain that his children are still at the Collège de Genève. Orders have been given to arrest him if he returns to the canton".

Doctor Pollet is established with his wife in the commune of Samoëns.[1] He owned a large house in the Bérouze, in the mountains, where he lived with the Milliets for over a year. Their life was calm and pleasant; it was in Samoëns that his last child, Louise,[29] was born on January 15, 1854.[30] Alix and Paul made their first communion there on April 4, 1854.[29] In order to carry out their economic affairs, Louise Milliet regularly went to France, to visit her mother, or to Valence, near her husband's land.[29]

All their children went to school, including their daughters, as recommended by Fourierist principles, and to religious instruction classes.[31] Alix went to the nuns, Fernand was a boarder at the Collège Royal de Bonneville and Paul was taught by a young vicar.[29] However, they were growing up and needed a more complete education. Félix Milliet, who has meanwhile taken up painting again, is asked to teach drawing at the Collège de Bonneville.[29] The Milliet family moved to Bonneville and he began his work in November 1854.[1][25] Their daughter Jeanne, whom Louise Milliet had been able to repatriate to Bonneville a few months earlier,[32][33] died at the age of six in November 1854, carried off by an unknown illness.[29]

The Phalansterian project of La Réunion[edit]

Félix and Louise Milliet found it increasingly difficult to cope with the authoritarian policies of Napoleon III. He found hope in a project led by an "excellent friend", the Fourierist Victor Considerant.[1][29][23] The latter planned to start a Fourierist community in Texas. The first settlers embarked in 1854 and founded La Réunion.[34]

Félix Milliet saw himself as a horse breeder,[1] running a stud farm with his wife and children. To do this, the Milliets needed substantial funds. Louise Milliet sold their house in Le Mans, their property in Saint-Flour, and made her dowry cash.[29] However, in 1857, Victor Considerant announced his failure and the liquidation of his company. He lost a large part of his funds, and the Milliets important sums of money.[29][14]

Voluntary exile to Geneva[edit]

The Milliets returned to Geneva in 1858[25] with government permission to complete their children's education[35] and settled there for eight years.[36] Paul took art classes and Fernand joined the army in 1859, leaving without even telling his parents.[37] That same year, a law granting amnesty to politically convicted prisoners allowed Félix Milliet to return to France.[38]

Having sold their properties in Saint-Flour and Le Mans,[38] and in the absence of family ties on French territory (Louise Milliet's mother died in 1855[35] and her sister Noémie de Tucé was a noblewoman opposed to their ideas), the Milliets preferred Geneva. They felt comfortable there and met their friends.[38] It was only after Alix married a Parisian, Henri Payen,[38] in 1861,[31] and Paul joined the Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1863,[38] that they returned to France in 1866, and settled in Paris. Their exile lasted a total of fourteen years.[35]

Return to France at the Colony[edit]

Early years[edit]

In Paris, the Milliet couple acquired a flat at 95 boulevard Saint-Michel, on the left bank,[39] provided by their daughter Alix Payen,[35] who was living in the 10th arrondissement[40] on the other bank. They joined the Fourierist community of La Colonie, organised around a phalanstery in the forest of Rambouillet, in Seine-et-Oise,[36] with which they had been in contact since the early 1860s.[8] They visited it regularly and spent their summers there.[36]

Of Félix Milliet's activity at the Colony during these early years, there is a testimony from his daughter Louise Milliet. In a letter dated September 21, 1868, she wrote: "every morning, Papa, Mr de Curton, Mme [Marie] de Boureulle and Mr [Eugène] Nus discuss philosophy, but I do not listen to them, because they are materialistic except for Mr Nus". Félix and Louise Milliet found some of their friends from Le Mans at Condé, such as Julien Chassevant, a shareholder since 1863 who was a director there for six years in the 1880s, and Marie Pape-Carpantier, whom they introduced to the community.[9]

According to Paul Milliet's texts, life there is made up of games, reading, music, paintings, walks and conversations.[41] Félix Milliet kept a garden which he cultivated.[39] During the 1860s, the Colony benefited from major developments, such as the construction of buildings and a vegetable garden covering half a hectare, and the creation of a school. In particular, Félix Milliet was responsible for the construction of an artistic kiosk in 1869,[1][42] and Louise Milliet had an orchard planted.[8]

Warfare in Paris[edit]

From then on, when Louise Milliet and their children moved, Félix Milliet did not leave the colony.[8][43] Thus, when Paris was under siege during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and the whole family was in town, he was not there.[39] Louise Milliet and her daughter Louise had to flee the bombardment of their neighbourhood in January 1871 and took refuge with friends or with Alix Payen,[44] while Paul Milliet and Henri Payen took part in the fighting.[39]

The capitulation of the provisional government - captured by the enemy, Napoleon III was defeated and a Third Republic was proclaimed on 4 September 1870 - was signed on January 28, 1871,[45] which allowed the whole Milliet family to meet again at Condé-sur-Vesgre,[46] until they were separated again due to the siege of the French army on the insurrection of the Paris Commune.[1][47] Paul Milliet and Alix Payen joined the armed ranks of the communards, the former as a member of the military engineer corps of the National Guard and the latter as an ambulance driver; Henri Payen, also a National Guard, was killed. Louise Milliet chose to stay in Paris to be with her children.[45] With her daughter Louise and their friend Marie Delbrouck (daughter of Joseph Louis Delbrouck), they regularly visited the wounded communards in the Luxembourg and then Saint-Sulpice ambulance.[48] They managed to maintain a regular correspondence with Félix Milliet,[49][50] sharing the events they attended, their activities and their communard opinions. The mother, Louise Milliet, was the most divided, the youngest daughter the most radical.[51] Alix Payen reports a concert where a mobile guard sings a song by Félix Milliet, Anathema to the coward criminal, written after the December 2.[52]

Retirement[edit]

The Milliets managed to get out of Paris and escape the repression.[53][54] Their life resumed in Condé-sur-Vesgre, in Paris, where Louise Milliet and her two daughters Alix and Louise were living, and in Geneva, where they all three regularly visited Paul, who was a refugee there.[55] Indeed, he was sentenced in absentia to deportation. Louise Milliet took numerous steps to obtain his pardon, which was only obtained in 1879.[56] The death of Henri Payen caused Félix Milliet to lose funds, as he had advanced him money to set up as a self-employed artisan.[54]

In 1872, their great friend Jacques François Barbier returned from his exile in Jersey and then in Lisbon, and settled in La Sarthe. The Milliet and Barbier families thus renewed their relationship. They went so far as to form an alliance,[14][19] with the marriage in October of the same year of Fernand Milliet and Euphémie Barbier, daughter of Jacques François Barbier.[7] Alix Payen returned to the Colony in the 1880s, after being widowed for a second time. She regularly visited her father.[23]

Félix Milliet spent his last fifteen years in the Colony, "surrounded by a few friends", he wrote. He no longer wrote political songs and devoted his life to literature, painting and horticulture, a life he described as "quite useless".[1] In 1879, he had a series published by the newspaper Publicateur, called Laure d'Arona.[27] In 1882, he translated the dramatic play The Triumph of Love by the Italian Giuseppe Giacosa, inspired by the work of the 15th-century poet Pétrarque, which was published in Le Mans.[57] Julien Chassevant's daughter, Marie Chassevant, was a composer[13] and wrote a collection of Scènes enfantines pour chant et piano with Félix Milliet in 1885.[29]

Louise Milliet's role within the Colony[edit]

Louise Milliet played a very important role in the colonny.[8] A member since 1862 from Geneva, she was, like her husband, a shareholder and held five shares in the capital of the Société civile immobilière of Condé.[7][41] The company owned the land and buildings of the community, which it rented to the settlers.[41] Louise was a member of the society's organisation for ten years, from 1865 to 1875, in which she served as vice-president twice, from 1866 to 1868 and from 1869 to 1872, before becoming president from 1873 to 1875. Between the springs of 1868 and 1869, as well as those of 1872 and 1873, she was not a member of the society.[8]

She was also the director of the Societary Household, an organisation that brought together the members of the Colony at an unknown date and for an unknown duration,[8] and was responsible for organising their daily life.[41] In 1872, she was a member of an interim executive committee responsible for responding to the projects decided during a phalanstery congress held the same year and managing a periodical entitled Bulletin du mouvement social,[41] which lasted until 1879. Louise and Marie de Boureulley were the only women. She also participated in various banquets between Phalansterians, such as in 1875 alongside Marie de Boureulle, Victor Considerant, Eugène Nus, Édouard de Pompéry and Eugène Bonnemère.[8]

Death and posterity[edit]

Félix Milliet died on October 22, 1888, in the 5th arrondissement of Paris.[1] Louise Milliet followed him five years later, on July 10, 1893. At his funeral, Gustave Chatelet read a eulogy by Eugène Nus: "In the name of the Colony, which she loved with all her heart and all her intelligence for the seed of progress that she saw in the future, the members of this societary household, to which she was so useful and where she leaves such a great void, send to the one they have just lost the homage of their profound regrets and their ineffaceable memory.

Only their last daughter, Louise Milliet, had any offspring.[58] Although her parents lost most of their fortune in their misadventures,[56] she inherited the assets of the whole family and of an uncle general, which enabled her to lead a wealthy and capitalist life.[58] Following in her parents' footsteps, she is a member of the community of La Colonie, where she raises her two children.

In 1904, Paul Milliet published posthumously in Paris a last collection of verses written by his father, entitled Rimes intimes.[59] After contacting the writer Charles Péguy, he published a family biography in the latter's periodic, Cahiers de la Quinzaine, which appeared between 1910 and 1911. As an introduction, Péguy wrote his essay Notre Jeunesse, one of his major works. The biography, which ensures that the Milliet family is not forgotten, is not well received by the readership,[60][19][1] and Péguy does not continue the contract beyond eleven books. Paul Milliet nevertheless wrote two more, which he had published by Georges Crès. His biography includes extracts from letters and diaries, and retraces the life of each member of the family;[60] his sister Alix Payen's letters written during the Paris Commune enjoy a little notoriety.[61] Concerning the biographical account of Félix and Louise Milliet, the researcher Colette Cosnier notes that Paul Milliet "embellishes reality, making his father's banishment into a rocky tale that is contradicted by the file kept in the Departmental Archives of Sarthe", that his account of La Colonie remains succinct and that "his memory is very selective: the Milliets were living in Le Mans at the time when Doctor [Auguste] Savardan wanted to change the lives of the Sarthe peasants through Fourierism, yet his name never appears in this book; the failure of Reunion is barely mentioned. So many "omissions" or gaps that may be attributed to the friendship between the Milliets and [Victor] Considerant", Auguste Savardan and Victor Considerant having fallen out.

Political ideas[edit]

Félix Milliet was, throughout his life, deeply republican.[14][58] He became politically active as soon as he began his studies in Paris during the Three Glorious Years in 1830. Even when he could not be active, during his military career, he respected his values, refusing, for example, to add the name of his property in Saint-Flour to his name, which was a condition for his marriage to Louise de Tucé.[7] He was introduced to the utopian socialist theses developed by Charles Fourier, called Fourierism, by his friends in Le Mans, in particular Julien Chassevant.

The songs he wrote demonstrate this republicanism,[10][14] but they only hint at his Fourierism, and few written records confirm his belief in Fourier's theories. His son Paul Milliet writes of him and Louise Milliet that "The phalanstery, with its harmonious organisation of attractive work by means of series, seemed to them to be the remedy that would regenerate the world. With the logic of a deep conviction, they always put these doctrines into practice and allowed their children the greatest freedom in the choice of work and pleasure. If my brother was a soldier, if I was a painter, it is because the attractions are proportional to the destinies", but this testimony, taken from the family biography, is based on a partisan account that embellishes reality.[1] During his lifetime, Napoléon Gallois described Félix Milliet's texts as "faith in a future [...] of world harmony", Fourierist terminology[1] characterising the utopian idea shared by Milliet, where the happiness of each individual is in harmony with that of humanity.[17]

Félix Milliet supported the June Days uprising, in which Parisian workers confronted the army of the Second Republic in 1848,[17] with his poems. He declared himself a socialist, but did not wish to give up the privileges granted to him by his bourgeois status, and enjoyed them.[1][56] Consequently, he opposed the class conflict.[10] According to Alfred Saffrey in the Cahiers de l'Amitié Charles Péguy, approved and taken up by Colette Cosnier, Milliet developed from Fourier's writings a "socialism in his own measure", in which the social question was resolved "by distributing to each person the work that he does with pleasure".[1][10] The harmony and social system he wanted to develop was based on the phalanstery system; he saw exile to a phalanstery in Texas as a personal solution to the authoritarianism of Napoleon III.[1]

We are meant to live together,

Harmony is the normal state;

Let's go so that a single link brings together

Work, talent and capital.

That to the work henceforth common

Each one bring with ardour

The one his arms, the other his fortune,

The other his genius and his heart.— Marchons en frères, Paris, 1850

On religious matters, Félix Milliet opposed the clergy. Thus, in the years following his marriage, his wife Louise Milliet - who also became a republican -, with a Catholic education, no longer practised. When he joined Freemasonry at the "Lodge of Arts and Commerce" in Le Mans, he proclaimed himself "liberated from the false doctrines of an ascetic spiritualism".[10] This reversion was particularly pronounced in 1855, due to the sequestration of an aunt of Louise Milliet in a convent and the attempt by the abbot[35] to monopolise her inheritance. Towards the end of his life, he affirmed his support for his daughter when she refused a marriage to the politician Étienne Dujardin-Beaumetz because he wanted to marry in church.[62]

Works[edit]

Poetry[edit]

- Roman d'amour (in French). 1838–1845.

- Chansons (in French). 1848–1849.

- Chansons politiques (in French). 1852–1854.

- Vers et chansons (in French). Monnoyer. 1848. p. 11.

- Marchons en frères (in French). Paris: imprimerie de Moquet. 1850. p. 4. OCLC 457901306.

- Son retour (in French). Le Mans: chez Granger. 1850.

- Chansons de Félix Milliet (in French). Paris: Propagande démocratique sociale, imprimerie de Schiller. 1850. p. 64. OCLC 457901300.

- Chansonnier impérial pour l'an de grâce 1853 (in French). Lausanne: chez Granger. 1852.

- Scènes enfantines pour chant et piano (in French). Paris: J. Hammelle. 1885. p. 28. OCLC 844187282.

- Rimes intimes (in French). Paris: librairie de la Plume. 1904. p. 127. OCLC 457901361.

Theatre[edit]

- Fol Amour (in French). 1862.

- Sigismond ou la vie est un songe (in French).

- La Tempête (in French).

- Almanzor et Zuleïma (in French).

- La Morisque (in French). 1868.

- Le Geôlier de soi-même (in French). 1869.

- Le Triomphe d'amour : Légende dramatique en deux actes, en vers (in French). Paris: imprimerie et libraire E. Lebrault. 1882. p. 83. OCLC 459345272.

Novel[edit]

- Laure d'Arona (in French). 1879.

Appendices[edit]

Related articles[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Milliet, Paul (1910a). "Les Milliet, une famille de républicains fouriéristes". Cahiers de la Quinzaine (in French).

- Milliet, Paul (1915–1916). "Une famille de républicains fouriéristes, les Milliet". Cahiers de la Quinzaine (in French). Paris: M. Giard and E. Brière.

- Saffrey, Alfred (March 15, 1971). "Paul Milliet : Une famille de républicains fouriéristes". Feuillets mensuels / l'Amitié Charles Péguy (in French) (166). Paris: M. Giard and E. Brière: 9 to 28.

- Vuilleumier, Marc (1981). La propagande républicaine à Genève. Vol. 2. Jean-Daniel Candaux et Bernard Lesclaze (dir.). Geneva: Librairie Droz and Société d'histoire et d'archéologie de Genève. p. 352. ISBN 2-6000-5068-X.

- Audin, Michèle; Payen, Alix (2020). C'est la nuit surtout que le combat devient furieux - Une ambulancière de la Commune, 1871. La petite littéraire. Libertalia. ISBN 978-2-37729-134-2.

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Read on line ou on Wikisource.

- ^ a b "Gallois Napoléon". Le Maitron en ligne (in French). February 20, 2009.

- ^ Colette, Cosnier; Bernard, Desmars (March 2011). "Chassevant, Julien". Dictionnaire biographique du fouriérisme (in French).

- ^ a b c d e Gérard, Boëldieu (February 20, 2009). "Barbier Jacques, François". Le Maitron en ligne (in French).

- ^ a b Le Bonhomme manceau (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France. 1849 – via BnF Catalogue général.; "Le Bonhomme manceau". Presse locale ancienne (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ^ "Silly Jean". Le Maitron en ligne (in French). February 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Jacques Bonhomme (Le Mans) (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France. 1851 – via BnF Catalogue général.; "Jacques Bonhomme". Presse locale ancienne (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ^ Le Petit bonhomme manceau (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France. 1851 – via BnF Catalogue général.; "Le Petit bonhomme manceau". Presse locale ancienne (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ^ Read online.

- ^ Michel, Cordillot (June 4, 2014). "Savardan Auguste (parfois prénommé Augustin)". Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement social francophone aux États-Unis (in French). Le Maitron en ligne.; Colette, Cosnier; Bernard, Desmars (June 4, 2014). "Savardan Auguste (parfois prénommé Augustin)". Dictionnaire biographique du fouriérisme (in French).

- ^ Philippe Gondard de l'Association pour l'étude du patrimoine sarthois (January 4, 2016). "L'insurrection de La Suze (1851)". Histoire du canton de La Suze sur Sarthe (in French).

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Colette, Cosnier. Milliet (Jean-Joseph-) Félix (in French). Dictionnaire biographique du tourisme. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Acte de mariage de Joseph Milliet et Élisabeth Vialet at Valence, p. 941.

- ^ Acte de naissance de Félix Milliet, on July 20, 1811, at Valence, p. 47.

- ^ Acte de mariage de Denis Laurent de Montlovier et Françoise Élisabeth Célie Milliet, on Fébruary 2, 1829 at Valence, p. 895-896.

- ^ Maurice, Mesnil (1871). Notes sur une famille de républicains fouriéristes, les Milliet (PDF). p. 16.

- ^ a b Milliet (1910b). Premier cahier, "Jusqu'au seuil de l'exil". p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Saffrey (1971, p. 12)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Milliet (1900). "Jusqu'au seuil de l'exil".

- ^ a b c d e f g (France), Le Mans (1839). Affiches, annonces judiciaires, avis divers du Mans, et du département de la Sarthe (in French). Le Mans. p. 276.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Saffrey (1971, p. 13)

- ^ (France), Le Mans (1839). Affiches, annonces judiciaires, avis divers du Mans, et du département de la Sarthe (in French). Le Mans. p. 276.

- ^ Sarane, Alexandrian (1979). Le socialisme romantique (in French). Paris: Editions du Seuil. p. 198. ISBN 2-02-005052-8.

- ^ a b c Paul, Delaunay (1913). Histoire de la Société de médécine du Mans et des Sociétés de la Sarthe (in French). pp. 54 and 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colette, Cosnier (1999). "Marie Pape-Carpantier, les fées et l'architecte". Histoire de l'éducation (in French). 82 (82): 143–157. doi:10.3406/hedu.1999.3071.

- ^ a b c Colette, Cosnier; Bernard, Desmars (2011). Chassevant Julien (in French). Dictionnaire biographique du fouriérisme. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Fortuné, Legeay (1859). Recherches historiques sur Mayet, Maine (in French). Dehallais et Du Temple. p. 353.

- ^ a b c Milliet (1900). Jusqu'au seuil de l'exil (in French). p. 88.

- ^ Jean, Touchard (1968). La Gloire de Béranger (in French). Presses de Sciences Po. pp. 291–292. ISBN 978-2-7246-8475-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vuilleumier (1981, p. 283)

- ^ Paul, Boiteau (1860). Correspondance de Béranger (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: Perrotin. p. 372.

- ^ Milliet (1910a, p. 88)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Saffrey (1971, p. 14)

- ^ a b c d e Michael Sibalis; Gauthier Langlois (February 20, 2009). "Trouvé-Chauvel Ariste, Jacques, Trouvé, dit". Le Maitron en ligne (in French). Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Patrick Lagoueyte (2016). Le Coup d'État du 2 décembre 1851 (in French). CNRS Éditions. pp. 236 and 166. ISBN 978-2-271-09392-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vuilleumier (1981, p. 284)

- ^ Gérard Duc (April 8, 2020). "Abraham LouisTourte". Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (in French).

- ^ a b "Péguy et les Milliet". Littérature et société : Recueil d'études en l'honneur de Bernard Guyon (in French). Éditions Desclée de Brouwer. 1973. p. 153.

- ^ Hans Bessler (1930). V. Attinger (ed.). La France et la Suisse de 1848 à 1852 (in French). p. 225.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Saffrey (1971, p. 15)

- ^ Birth certificate of Stéphanie Louise Milliet, January 17, 1854, in Samoëns.

- ^ a b Audin & Payen (2020, p. 11)

- ^ Milliet (1910b, deuxième cahier, Les Adieux, p. 75)

- ^ Milliet (1910b, deuxième cahier, Les Adieux, p. 64)

- ^ Jean-Claude, Dubos; Michel, Cordillot (January 27, 2009). "Considerant Victor [Considerant Prosper, Victor]". Le Maitron en ligne (in French). Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Saffrey (1971, p. 16)

- ^ a b c Saffrey (1971, p. 19)

- ^ Saffrey (1971, p. 17)

- ^ a b c d e Saffrey (1971, p. 18)

- ^ a b c d Audin & Payen (2020, p. 16)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 12)

- ^ a b c d e Bernard Desmars (2010). Militants de l'utopie ? : Les fouriéristes dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle (in French). Dijon: Les Presses du réel. pp. 181 and 185. ISBN 978-2-84066-347-8.

- ^ Danielle Duizabo (2003). Chronologie colonienne, 1832 - 1878 (PDF) (in French). p. 5.

- ^ Saffrey (1971, p. 20)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 23)

- ^ a b Saffrey (1971, p. 22)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 30)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 31)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 39)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 34)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 77)

- ^ Maïté Bouyssy (August 13, 2019). "Aux grandes femmes la Commune reconnaissante". En Attendant Nadeau (in French) (109).

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, pp. 11 and 80)

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, pp. 102–103)

- ^ a b Saffrey (1971, p. 23)

- ^ Saffrey (1971, p. 24)

- ^ a b c Saffrey (1971, p. 26)

- ^ "Le Triomphe d'amour". La Jeune France: 58. May 1, 1882.

- ^ a b c Saffrey (1971, p. 27)

- ^ Jean Joseph Félix Milliet. "J.-J.-Félix Milliet, 1811-1888. Rimes intimes [Printed text]". BnF catalogue général. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Saffrey (1971, pp. 26–28)

- ^ Édith Thomas (1963). Les Pétroleuses (in French). Éditions Gallimard. p. 159. ISBN 2-07-026262-6.

- ^ Audin & Payen (2020, p. 65)