Draft:Kashmiris in Pakistan

| Submission declined on 6 May 2024 by Saqib (talk). The proposed article does not have sufficient content to require an article of its own, but it could be merged into the existing article at Kashmiris in Azad Kashmir. Since anyone can edit Wikipedia, you are welcome to add that information yourself. Thank you.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4-8 million [citation needed] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Punjab, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Sindh | |

| Languages | |

| Kashmiri, Punjabi, Urdu, Pahari-Pothwari | |

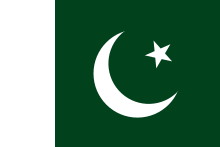

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kashmiri Diaspora, Kashmiris in Punjab & Kashmiris in Azad Kashmir |

The Kashmiris in Pakistan, also referred to as Kashmiri-Pakistanis or Pakistani Kashmiris, are Pakistani citizens of full or partial ethnic Kashmiri heritage. From the early 1800s to 1990s, millions of ethnic Kashmiris began arriving in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan from the Kashmir Valley, constituting major segments in Pakistani society.

History[edit]

Pre-Partition[edit]

Heavy commodifications taxation under the Sikh rule caused many Kashmiri peasants to migrate to the plains of Punjab.[1][2] These claims, made in Kashmiri histories, were corroborated by European travelers.[1] When one such European traveller, Moorcroft, left the Valley in 1823, about 500 emigrants accompanied him across the Pir Panjal Pass.[3] The 1833 famine resulted in many people leaving the Kashmir Valley and migrating to the Punjab, with the majority of weavers leaving Kashmir. Weavers settled down for generations in the cities of Punjab such as Jammu and Nurpur.[4] The 1833 famine led to a large influx of Kashmiris into Amritsar which was also under Sikh rule.[citation needed] Kashmir's Muslims in particular suffered and had to leave Kashmir in large numbers, while Hindus were not much affected.[5] The emigration during the Sikh rule resulted in Kashmiris enriching the culture and cuisines of Amritsar, Lahore and Rawalpindi.[6] Sikh rule in Kashmir ended in 1846 and was followed by the rule of Dogra Hindu maharajahs who ruled Kashmir as part of their princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.[7]

A large number of Muslim Kashmiris migrated from the Kashmir Valley[8] to the Punjab due to conditions in the princely state[8] such as famine, extreme poverty[9] and harsh treatment of Kashmiri Muslims by the Dogra Hindu regime.[10] According to the 1911 Census there were 177,549 Kashmiri Muslims in the Punjab. With the inclusion of Kashmiri settlements in NWFP this figure rose to 206,180.[11]

Scholar Ayesha Jalal states that Kashmiris faced discrimination in the Punjab as well.[12] Kashmiris settled for generations in the Punjab were unable to own land,[12] including the family of Muhammad Iqbal.[13] Scholar Chitralekha Zutshi states that Kashmiri Muslims settled in the Punjab retained emotional and familial links to Kashmir and felt obliged to struggle for the freedom of their brethren in the Valley.[14]

Common krams (surnames) found amongst the Kashmiri Muslims who migrated from the Valley[8] to the Punjab include Butt,[15][16][17] Dar,[15] Lone , Wain (Wani), Mir, Rathore.

Post-Partition[edit]

With the accession of Kashmir to the Indian state, Kashmiris began to initiate more migrations to Pakistan. The Neelam and Leepa Valleys in northern Azad Kashmir are home to a significant Kashmiri Muslim population, as these areas border the Kashmir Valley.[18] Kashmiris who support their state's accession to Pakistan or had ties to pro-Pakistani separatist parties left their homes out of fear of persecution, settling on the Pakistani side of the border. Some of them came from places as distant as Srinagar.[19]

There are also Kashmiri populations spread out across the districts of Muzaffarabad[20] The first wave of Kashmiri refugees arrived in 1947–48 against the backdrop of the partition of British India. More refugees poured in during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 and Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, followed by a third wave in the 1990s as a result of the insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir.[20] These refugees included people from the Kupwara and Baramulla districts of Kashmir.[19] Farooq Haider Khan, Azad Kashmir's prime minister, claimed that as many as 2.2 million people from Jammu and Kashmir sought refuge in Azad Kashmir between 1947 and 1989.[21]

Kashmiris in Pakistani administered regions also held onto their roots in varying ways. Altaf Mir is a Kashmiri settler and singer from Muzaffarabad whose rendition of the classical Kashmiri poem, Ha Gulo, on Coke Studio Explorer remains widely popular and was the first Kashmiri song featured on the show.[22][23] The city of Muzaffarabad is known for its Kashmiri shawls, which are an iconic product of Kashmir.[24]

Kashmiri Muslims constituted an important segment of several Punjabi cities such as Sialkot, Lahore, Amritsar and Ludhiana.[25] Following the partition of India in 1947 and the subsequent communal unrest across Punjab, Muslim Kashmiris living in East Punjab migrated en masse to West Punjab. Kashmiri migrants from Amritsar have had a big influence on Lahore's contemporary cuisine and culture.[26] The Kashmiris of Amritsar were more steeped in their Kashmiri culture than the Kashmiris of Lahore.[27] Ethnic Kashmiris from Amritsar also migrated in large numbers to Rawalpindi,[28] where Kashmiris had already introduced their culinary traditions during the British Raj.[29]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 9781850656944.

Kashmiri histories emphasize the wretchedness of life for the common Kashmiri during Sikh rule. According to these, the peasantry became mired in poverty and migrations of Kashmiri peasants to the plains of the Punjab reached high proportions. Several European travelers' accounts from the period testify to and provide evidence for such assertions.

- ^ Schofield, Victoria (2010). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857730787.

The picture painted by the Europeans who began to visit the valley more frequently was one of deprivation and starvation...Everywhere the people were in the most abject condition, exorbitantly taxed by the Sikh Government and subjected to every kind of extortion and oppression by its officers...Moorcroft estimated that no more than one-sixteenth of the cultivable land surface was under cultivation; as a result, the starving people had fled in great numbers to India.

- ^ Parashar, Parmanand (2004). Kashmir The Paradise Of Asia. Sarup & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 9788176255189.

What with the political disturbances and the numerous tyrannies suffered by the peasants, the latter found it very hard to live in Kashmir and a large number of people migrated to the Punjab and India. When Moorcroft left the Valley in 1823, about 500 emigrants accompanied him across the Pir Panjal Pass.

- ^ Kashmir Under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. 1984. p. 20. ISBN 9788171560943.

In the beginning, it was only the excess of population that was increasing rapidly, that started migrating into Punjab, where in the hilly cities of Nurpur and Jammu, that remained under the rule of Hindu prince the weavers had settled down for generations...As such, even at that time, a great majority of the weavers have migrated out from Kashmir. The great famine conditions and starvation three years earlier, have forced a considerable number of people to move out of the valley and the greater security of their possessions and property in Punjab has also facilitated this outward migration...The distress and misery experienced by the population during the years 1833 and 1834, must not be forgotten by the current generation living there.

- ^ Parashar, Parmanand (2004). Kashmir The Paradise Of Asia. Sarup & Sons. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9788176255189.

Moreover, in 1832 a severe famine caused the death of thousands of people...Thus emigration, coupled with the famine, had reduced the population to one-fourth by 1836...But still the proportion of Muslims and Hindus was different from what it is as the present time in as much as while the Hindus were not much affected among the Muslims; and the latter alone left the country in large numbers during the Sikh period.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ali2011was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849046220.

- ^ a b c Bose, Sumantra (2013). Transforming India. Harvard University Press. p. 211. ISBN 9780674728202.

From the late nineteenth century, conditions in the princely state led to a significant migration of people from the Kashmir Valley to the neighboring Punjab province of British-as distinct from princely-India.

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (2002). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. p. 352. ISBN 9781134599387.

Extreme poverty, exacerbated by a series of famines in the second half of the nineteenth century, had seen many Kashmiris fleeing to neighbouring Punjab.

- ^ Chowdhary, Rekha (2015). Jammu and Kashmir: Politics of Identity and Separatism. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 9781317414056.

Prem Nath Bazaz, for instance, noted that 'the Dogra rule has been Hindu. Muslims have not been treated fairly, by which I mean as fairly as Hindus'. In his opinion, the Muslims faced harsh treatment 'only because they were Muslims' (Bazaz, 1941: 250).

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (2002). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. ISBN 9781134599387.

According to the 1911 census there were 177, 549 Kashmiri Muslims in the Punjab; the figure went up to 206, 180 with the inclusion of settlements in the NWFP.

- ^ a b Jalal, Ayesha (2002). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. p. 352. ISBN 9781134599370.

...Kashmiris engaged in agriculture were disqualified from taking advantage of the Punjab Land Alienation Act...Yet Kashmiris settled in the Punjab for centuries faced discrimination.

- ^ Sevea, Iqbal Singh (2012). The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism in Late Colonial India. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781139536394.

Like most Kashmiri families in Punjab, Iqbal's family did not own land.

- ^ Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 191–192. ISBN 9781850656944.

Kashmiri Muslim expatriates in the Punjab had retained emotional and familial ties to their soil and felt compelled to raise the banner of freedom for Kashmir and their brethren in the Valley, thus launching bitter critiques of the Dogra administration.

- ^ a b Explore Kashmiri Pandits. Dharma Publications. ISBN 9780963479860. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ The Journal of the Anthropological Survey of India, Volume 52. The Survey. 2003. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

The But/Butt of Punjab were originally Brahmin migrants from Kashmir during 1878 famine.

- ^ P.K. Kaul (2006). Pahāṛi and other tribal dialects of Jammu, Volume 1. Eastern Book Linkers. ISBN 9788178541013. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

The But/Butt/ of Punjab were originally Brahmin migrants from Kashmir during 1878 famine.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Snedden2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cabeiri deBergh Robinson (8 March 2013). Body of Victim, Body of Warrior: Refugee Families and the Making of Kashmiri Jihadists. University of California Press. pp. 19, 52, 61, 62. ISBN 978-0-520-95454-0.

Many of these refugees spoke the Kashmiri language, had close ties with pro-Pakistan political parties, and were advocates of Kashmir's accession to Pakistan. Identified as pro-Pakistan activists, they left their homes to escape persecution.

- ^ a b Nizami, Ah (10 January 2012). "Disillusioned: Unfulfilled promises, discrimination add to Kashmiri refugees' plight". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Wani, Riyaz (2 October 2018). "Urgent need to explore human dimension of Kashmir conflict". Tehelka. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Mehraj, Irfan (26 September 2018). "A Kashmiri overnight music sensation recounts a grim past". TRT World. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Ganai, Naseer (30 July 2018). "How A Band Featured In Coke Studio Pakistan Is Winning Hearts In The Valley". Outlook India. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Naqvi, Mubashar (8 December 2017). "Kashmiri warmth for the winter". The Friday Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Sevea, Iqbal Singh (2012). The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism in Late Colonial India. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781139536394.

In the early twentieth century, famine and the policies of the Dogra rulers drove many Kashmiri Muslims to flee their native land and further augment the number of their brethren already resident in the Punjab. Kashmiri Muslims constituted an important segment of the populace in a number of Punjabi cities, especially Sialkot, Lahore, Amritsar and Ludhiana.

- ^ "Lahore, Amritsar: Once sisters, now strangers". Rediff News. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

The biggest influence on Lahore's contemporary culture and cuisine are the Kashmiris who migrated from Amritsar in 1947.

- ^ Hamid, A. (11 February 2007). "Lahore Lahore Aye: Lahore's wedding bands". Academy of the Punjab in North America. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

The Kashmiris of Lahore were not as steeped in their Kashmiri culture and heritage as the Kashmiris of Amritsar, which was why the Kashmiri Band did not last long.

- ^ Yasin, Aamir (2015-02-23). "A sip of Kashmir!". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2018-01-07.

- ^ Yasin, Aamir (2014-11-10). "The taste of Kashmir". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2018-01-07.