Church of Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu

| Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu Abbey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Region | Pays de la Loire, Loire-Atlantique |

| Leadership | Benedictines |

| Location | |

| Municipality | Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu |

| Country | France |

| Administration | Roman Catholic Diocese of Nantes |

| Geographic coordinates | 47°02′19″N 1°38′27″W / 47.0386374°N 1.6409178°W |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Carolingian |

The Church of Saint-Philibert de Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu is an abbey founded in the 9th century by Benedictine monks and located in Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu, France. All that remains is the abbey church and a few buildings around it.

With a Carolingian style building, it once housed the body of Saint Philibert, from whom the commune took its name. When the site was attacked by the Normans, the monks fled with the saint's body to Tournus. The community then reformed and founded a priory. Used as a covered market in the 19th century, the abbey church was no longer used for worship. Excavations unearthed the saint's sarcophagus, and the building was listed as a historic monument in 1896. The abbey church has been used for religious worship since 1936. Today, it is one of the most important monuments open to visitors in the Pays de Retz region.

History[edit]

Middle Ages[edit]

Early Middle Ages[edit]

The abbey church was built around 815 on the land of an ancient estate called Déas (now Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu), given to the monk Saint Philibert in the 6th century. Dependent on the Abbey of Noirmoutier, it provided for the latter's needs.[1] Its construction was authorized by Louis I, Charlemagne's son.[2] The site was also safer from Viking raids, being located deeper inland. Indeed, Noirmoutier Abbey was attacked by the Normans on numerous occasions during the first half of the ninth century. As reported by Ermentaire, a young monk from Noirmoutier, the Benedictine monks opened the tomb of Saint Philibert on June 7, 836, took the Roman road via Bois-de-Céné and Paulx, and fled to Déas with the relics.[3] Under the leadership of Abbot Hilbod, the site was refitted to provide a more effective defense against looters.[4]

In 847, the Normans reached the parish. The attackers set fire to the abbey church and the monastery. The crypt was walled up, with the shrine containing the relics inside. Thus protected, the chasse was not damaged.[5] The monks rebuilt the abbey church, then moved to Tournus in Burgundy with the relics, leaving the shrine empty.

High Middle Ages[edit]

A priory was founded by the Tournus monks on the Déas site in the 11th century, under the Tournus abbey.[4][6] In 1119, the parish took the name Saint-Philibert-de-Grand-Lieu in honor of the monk Philibert.[7]

- Statue of Saint Philibert in the abbey church

-

-

-

-

Early modern period[edit]

During the 14th century, a wooden bell tower was erected above the abbey's entrance porch. During the Wars of Religion in the region, the Huguenots also caused damage to the site. In particular, they damaged the choir, the porch and the bell tower. In the 17th century, the church became a parish church.[5][8] Later, during the French Revolution, the abbey church was sold as national property in 1791. During the Vendée uprisings, the building was used by the Republicans as a fodder shed and ammunition depot.[7][8]

Late modern period[edit]

After the construction of the new parish church in 1869, the building was used as a market hall, and the cracked walls had to be reduced in height by 3 meters. However, the discovery of the tomb in 1865 finally restored interest in the site, and work was carried out between 1898 and 1904.[9] As a result, the abbey church was listed as a historic monument in 1896,[10] even though it was no longer in use. It wasn't until 1936 that it was reopened for worship.[11] The same year, a festival celebrated the eleventh centenary of the transport of the relics to the commune. A relic of Saint Philibert was placed in the sarcophagus.[5] Today, the monument is open to visitors, some 9,000 a year.[12] In addition to tours of the building and gardens, art and cultural exhibitions are held in the abbey church. Religious ceremonies are held from time to time, including the "Fête de la Saint-Philibert" (Saint Philibert's Day), with a vigil and a patron saint's mass.[13]

Abbey church[edit]

The abbey church is mainly in the Carolingian style. Modifications over time have added elements from other styles, notably the Romanesque. The appearance of the building has also been changed, both inside and out.

- Outside views

-

Facade and portal.

Facade and portal. -

Right side facade.

Right side facade. -

Back facade.

Back facade. -

Left side facade from the reconstructed garden.

Left side facade from the reconstructed garden.

Architectural features[edit]

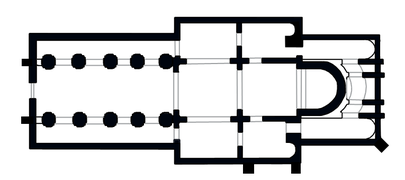

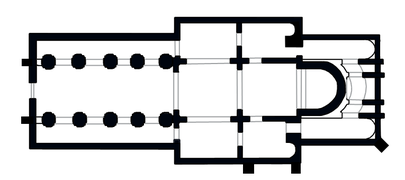

The current nave was rebuilt after 847, the first church dating from 815 was ruined by the Normans. It has four bays, whereas the former church had six. On the pillar closest to the choir, you can still distinguish the beginnings of an arch, the remains of one of the fourteen original pillars. The present ten pillars are cruciform, made of alternating stone and brick.[14] These pillars were originally lighter in weight, but were later reinforced. The arches date back to the Carolingian period. They are also characteristic of the style, with their alternating pattern of tuffeau stone and brick.[15] Reinforced between the 9th[14] and 11th centuries (the dating of this work has given rise to controversy, due to the scarcity of available documents[16]) by Romanesque arches, the walls were however levelled for safety reasons when the building was used as a chicken market. However, the base of the removed window openings can still be seen.[15]

The ambulatory has suffered the most damage over time. Originally, it consisted of three apsidioles, which were replaced after their destruction by a straight wall at chevet level. This was the site of the fenestella, the only opening, intended to be small so that it could be easily closed in the event of danger, and which enabled pilgrims to see and touch the relics.[17] This ambulatory was one of the first to be built in the West to handle the flow of pilgrims.[15]

The crypt, also known as the "confession", is located on the choir level of the abbey church. This is where Saint Philbert's sarcophagus is stored. In 836, Abbot Hibold ordered the construction of the crypt walls to protect the tomb from pilgrims. Pilgrims turned the crypt into a semi-buried space. In 847, the crypt was completely walled in to prevent the desecration of the tomb by Vikings.[5]

Following the construction of a new church in the 19th century, the town council decided to convert the abbey church into a market hall. The walls were lowered by three meters. To cover the building, it was decided to install a roof pierced with skylights. During restoration work between 1896 and 1903, the roof was redone.[15]

-

Abbey church plan.

Abbey church plan. -

Nave and choir

Nave and choir -

Nave and gate

Nave and gate -

Funerary monuments[edit]

The sarcophagus of Saint Philibert, located in the crypt, is Merovingian in style. Crafted towards the end of the 6th century, it is made from a single block of blue granite cut in the Pyrenean quarries of Saint-Béat. It is decorated with two Merovingian crosses, one at each end, and measures 2.05 meters long by 0.7 meters high (6.72 feet long by 2.29 feet high).[17] The saint, buried in 686 at Noirmoutier, was exhumed in 836 and transported in four days on a stretcher on men's backs to Déas. He was then returned to his place in his sarcophagus. It was then surrounded by a confessional to protect it from any damage caused by overeager pilgrims.[15] After the relics left for Tournus, the sarcophagus remained empty. Buried in the crypt, it was only found during excavations in 1865.[5]

There are two other funerary monuments in the abbey church. The memorial plaque Guntarius covers the tomb of a monk who was buried in the choir between the 9th and 10th centuries.[15] Guillaume Chupin's tombstone dates back to 1440, when this priest had a stone engraved under which he hoped to be buried. But for this to happen, he would have had to be appointed rector of the parish, as he had had engraved in advance, an appointment he did not obtain. On his death in 1449, he was therefore not buried under this stone (the places for the years, month and day are not engraved) which, from 1663, served as the table of the main altar (the stone was damaged on this occasion).[3]

-

Saint Philibert's sarcophagus.

Saint Philibert's sarcophagus. -

Saint Philibert's sarcophagus.

Saint Philibert's sarcophagus. -

Guillaume Chupin's tombstone.

Ornamentation[edit]

The stained glass windows are relatively recent. They were made when the abbey church was restored to worship in 1936, and are the work of master glassworker Jacques Grüber. However, these windows are based on medieval styles and techniques. The window above the high altar depicts Saint Philibert with his right hand raised in a gesture of blessing, and the boat carrying his sarcophagus from the Noirmoutier monastery. In the lower part of the window, two monks support the shrine, while a third, hands clasped, turns his head towards the audience, as if to encourage prayer. In the ambulatory there is a second-stained glass window, a representation of Saint Anne, whose cult the Philibertine monks imported to the region from Ireland.[17]

An ex-voto is carved directly into the tuffeau stone beneath the main altar. It reads "Aux ides de juin, dédicace au Dieu sauveur." (On the ides of June, dedication to God the Saviour). It is interpreted either as a dedication of the church, or as the ex-voto of a grateful pilgrim (the latter hypothesis seems weakened by the fact that there is no other ex-voto).[15]

The abbey church features a number of statues. There's a wooden statue of Saint Philibert, a polychrome wooden statue of the Madonna and Child, and a statue of Saint Anne and the Virgin. These two statues come from the chapel of the Manoir de l'Hommelais in the same commune.[15]

The painting Lamentation of Christ is on display in the abbey church. It once belonged to the Manoir de l'Hommelais in the commune of Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu. The painting was damaged by republicans during the Vendée uprisings, and has since been restored.[15]

The abbey church has several baptismal fonts. Five identical fonts were found during excavations, two of which are still in place. They date from the 11th - 13th centuries BC and feature sculpted faces that have eroded over time.[15] The baptismal fonts are proof of the abbey's function as a parish church after the return of the monks in the 11th century. They are unusual in that they have two basins, one for the holy water and the other for the baptismal water.[15] Lastly, the washbasin was originally intended for pilgrims to purify themselves before visiting the relics of Saint Philibert, In accordance with a medieval custom. The unusually high position of the washbasin dates back to the 1900 excavations, when the ground level was lowered by one metre.[15]

A key was found in the crypt, dating from the Carolingian period. Its handle follows the design of the nave.[15]

-

Statuary

Statuary -

Statue of a Madonna and Child

Statue of a Madonna and Child -

Statue of a Madonna and Child

Statue of a Madonna and Child -

Statue of Saint Anne

Statue of Saint Anne -

Statue of a martyr or Saint Joseph

Statue of a martyr or Saint Joseph -

-

Abbey church key

Abbey church key

Around the abbey church[edit]

Around the abbey church are the former parts of the abbey. The medieval garden, also known as the jardin des simples, it comprises three areas between the abbey church and the Boulogne river: the cloistered garden, the cemetery orchard and the medicinal garden.[7]

The priory is a building built in continuity with the facade of the abbey church. It was built on the site of the former monastery, burnt down by the Normans in 847. Six monks occupied the site and raised it from the ruins. The priory was in a poor state and underwent restoration in 1762. During the French Revolution, the priory building was sold as national property on November 8, 1791, for the sum of 10,000 francs,[15] in accordance with the Décret des biens du clergé mis à la disposition de la Nation of November 2, 1789. In 1993, the building was purchased by the municipality and is now occupied by the local tourist office.[7]

A former outbuilding of the abbey church with schist walls, dating from the 15th to 16th centuries, houses a bird and mineralogical museum.[15]

See also[edit]

- Saint Philibert

- Church of St. Philibert, Tournus

- Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu

- Saint-Philibert de Noirmoutier Abbey

References[edit]

- ^ "Histoire et patrimoine - Découvrir Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu". Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu Town hall (in French). Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu -Présentation de la commune". Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu Town hall (in French). Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Nicole Mesnier, André Papin and Odile Baud (1994). Abbatiale ixe siècle Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu (in French). pp. 9–11.

- ^ a b Nicole Mesnier, André Papin and Odile Baud (1994). Abbatiale ixe siècle Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu (in French). p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e "Abbatiale Saint-Philibert". structurae.de. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ "Patrimoine - L'abbatiale". paysderetz.info (in French). Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Emilie Mercier, Sarah Sanchez, Geneviève Ouvrard, Jean-Paul Labourdette (2009). Petit Futé (in French). Nouvelles Editions de l'Université. p. 342. ISBN 978-2-7469-2511-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Nicole Mesnier, André Papin and Odile Baud (1994). Abbatiale ixe siècle Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu (in French). p. 15.

- ^ Nicole Mesnier, André Papin and Odile Baud (1994). Abbatiale ixe siècle Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu (in French). p. 18.

- ^ "Notice No. PA00108819". Base Mérimée.

- ^ "Abbatiale : une convention entre la ville et le diocèse - Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu". Ouest-France. ISSN 0999-2138.

- ^ "La région des Pays de la Loire et le département de la Loire-Atlantique s'engagent aux côtés du pays de Grandlieu, Machecoul et Logne et de ses communautés de coummunes" (PDF). www.paysdelaloire.fr. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2010..

- ^ "Plaquette été du site de l'abbatiale" (PDF). Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu Town hall. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Nicole Mesnier, André Papin and Odile Baud (1994). Abbatiale ixe siècle Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu, Rennes, Ouest-France. p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Alexandre-Bidon, Compère, Gaulupeau, Verger, Bodé, Ferté, Marchand, Caspard (1999). Le Patrimoine Des Institutions Politiques Et Culturelles (in French). Paris: Flohic. pp. 1228–1234. ISBN 9782842340346.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dictionnaire des églises de France, Belgique, Luxembourg, Suisse, Bretagne (in French). Paris. 1968.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Nicole Mesnier, André Papin and Odile Baud (1994). Abbatiale ixe siècle Saint-Philbert-de-Grand-Lieu (in French). pp. 24–26.