Castle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (March 2016) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Castle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape | |

|---|---|

Château de Châteauneuf-du-Pape | |

| |

| Former names | castellum de Leri, Costro Npvo Chateauneuf de l'Hers (1200s) |

| General information | |

| Status | partially standing |

| Architectural style | Gothic |

| Location | Châteauneuf-du-Pape, France |

| Address | 18 Rue Carmagnole |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 44°03′27″N 004°49′47″E / 44.05750°N 4.82972°E |

| Construction started | 1317 |

| Completed | 1333 |

| Destroyed | Partially in 1940, during WWII |

| Client | John XXII |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 3 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Hugues de Patras Raymond d'Ébrard Guillaume Coste |

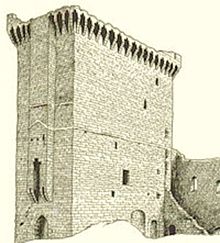

The Castle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape is a château located in the town of the same name in southeastern France. Its presence has dominated the landscape around the village and its renowned vineyards for more than 800 years.

History[edit]

The Castle of Châteauneuf was probably originally a Roman castrum destroyed during the great invasions. A 913 charter referred to the castellum de Leri.[1]

It also appeared under the name castellum de Leri in a 913 charter[2] signed by Louis the Blind which ceded the site to Foulques, bishop of Avignon. The castrum on the hill was replaced with new construction by the Count of Toulouse, the overlord of the comté of Provence. The first mention of a Castro Novo (new fortified village), which led to the name Châteauneuf, did not appear until 1048. It fell to Godefredus Lauger, Bishop of Avignon, and his successors, through an 1157 charter in which the emperor Barbarossa mentioned the presence of a vineyard. In 1077 Rostaing, his successor, deeded the fief to Pierre d'Albaron, who built a keep there. Throughout the Middle Ages, the old château was a watchtower and a toll gate on the Rhône that passed to various families allied to the house of Albaron.[3] Only a tower remained in 1146, and by 1283 it was already being referred to as "the old tower".[4]

It became the Château de l'Hers after it was enlarged in the 12th century, and it was renovated for the first time in the 13th.[5] Some historians say the Knights Templar used it in the 12th century,[6][1] but this legend was put to rest by 20th-century historians.[7]

Pontifical era[edit]

Châteauneuf, like Bédarrides or Gigognan, had a special status in the Comtat Venaissin when the Antipopes came to Avignon. Its high and low justices didn't fall under the Recteur du Comtat but instead under the bishop of Avignon. Its three parishes were said to be In Comitatu et non-de Comitatu[4]

Pope Clement V visited 5 April 1314 before he crossed the Rhône to join Roquemaure, about fifteen days before he died.[4]

Jacques d'Euze, previously the bishop of Avignon, was elected pope in 1316 and took the name John XXII. Châteauneuf fell directly under his authority. He had been Pope barely three months when he commissioned construction work at l'Hers. The accounts of the Apostolic Camera indicate that he allocated 3000 florins to the restoration of the 12-century château.[5][8]

Then in 1317 he decided to build a new château above the village. It was finished in 1333.[4] Due to its size and location its function was essentially defensive[9] At the same time, in 1318, he circled it with ramparts.[4]

The successors of Jean XXII rarely stayed at Châteauneuf[1][10] except when the plague threatened Avignon, and the papal court installed itself there.[11] That was the case in 1383.[12] Only Clement VII, the antipope from 1385 to 1387, had any maintenance done on the disused château. He also had the vines replanted. He was the pope who lived there the most.[10] His successor, the Antipope Benedict XIII, moved in during 1396 after he had done some restoration.[13]

After Popes' return to Rome[edit]

After the Great Western schism ended and the popes left Avignon, the will and the resources to maintain the château were lacking. The bishops and archbishops of Avignon, to whom it belonged, took little interest in it, which was left to fall into disrepair.[11]

It took on strategic importance again during the Wars of Religion. In 1562, Jean-Perrin Parpaille, whose family came from Châteauneuf, tried to take the château but was pushed back by the troops of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, the apostolic administrator of Avignon, and had to leave his munitions behind.[6] That made the historian Louis de Pérussis, in his work, Discours de guerre de la Comté de Venayscin et de la Provence (1563–1564), note: "The said Parpaille burned his fingers there and took some casualties then and shamefully withdrew to Orange.[4]

The Huguenots, led by Charles Dupuy de Montbrun, lieutenant of the Baron des Adrets, took the village and the castle, which had been abandoned after the Mornas massacre, in July 1562. They stayed until February 1563 and pillaged the entire region.[10][14] The building was abandoned by the Calvinists after the battle of Valréas. The Baron of Adrets retook the stronghold and burned down part of the château in March 1563.[14] His troops pillaged the salt warehouse and burned down the church.[10] They left only the keep and a swath of wall.[14]

When peace returned in 1578, what remained of the château was restored.[4] In 1580 Pope Gregory XIII granted to Jean-Baptiste d'Alphonse and his male descendants the title of the perpetual capitain of the château. This nomination was overturned by Pope Gregory XV in 1623 then restored in 1633 to Pierre d'Alphonse by Mario Philonardi, of Avignon. The title was then taken by Charles of Suarez, provicaire général of the archbishopric, who took possession of the château as well.[13]

Meanwhile, in 1584 Georges d'Armagnac, the archbishop of Avignon, took an ordonnance for the commune of Châteauneuf-Calcernier, known as "du Pape", to protect the vines.[15] In the next century, his successor, Hyacinthe Libelli, had the château redecorated and restored during 1681 so he could take up residence there.[4]

En 1728, François-Maurice Gontier, the new archbishop of Avignon, rented the building for 400 livres a year to an Irish noble named John, Baron of Powers,[4] who also leased l'enclos des papes, the papal enclave.[15] When harvest time came, the baron decided to send his wines through the port of Roquemaure. He was refused with the explanation that the wines of Châteauneuf were very inferior to those of Roquemaure because of their taste, de terroir.[15] The explanation lies in the presence of vines producing muscat sur ce terroir. The marquis de Tulle also found this in 1731, in the vineyard of the Château de la Nerthe.[16]

French Revolution[edit]

After the French Revolution Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin rejoined the republic in 1793, and the winegrowers could sell their production for one third more than the departmental maximum because the Châteauneuf wine was recognized as high quality in all seasons.[1] In 1798, the château and its domain were auctioned off to J.B. Establet who acted with the underwriting of 30 of his fellow citizens. A year later, the new owner resold it in equal to his backers, all of whom began to take down the walls of the château, either to sell to use or to use themselves the stones.[10][11]

In 1858 The ground floor of the keep was rented as a warehouse on condition the tenants allow visitors who wished to see it to do so. In 1892, the ruin was deeded back to the state and immediately classified as a historic monument.[11]

World War II[edit]

During World War II the Germans moved in. The keep was transformed; it served as an arms dépôt and a 115m anti-aircraft observation post. Operation Dragoon triggered a retreat of the occupation forces. The garrison of the château, which had been storing explosives and munitions, blew them up before leaving on 20 August 1944, destroying the entire northern part of the château. Only the cellar and the south side of the keep remained intact.[1][9][10] The west façade, while already in ruins, resisted the explosion and its windows show the layout of the château and its three floors.[17] A young Resistance fighter of the Francs-Tireurs Provençaux was killed near the château in June 1944. A commemorative plaque marks the spot.

Modern era[edit]

In 1960 the municipality decided to install a reception hall in the pontifical cellar. This great room of the castle has kept its original proportions. Twice a year, it serves as a prestige venue to the Échansonnerie des Papes, a confrérie bachique in Châteauneuf-du-Pape where it initiates new members. At these soirées, the inductees symbolically receive a key to the pope's cellar.[9][11]

Besides the soirées, a certain number of festivities are tied to the château, such as La Tauléjade, which presents the new vintages to wine professionals, the Fête de la Saint-Marc, when the previous three vintages, both red and white, can be tasted, and the Fête de la véraison, a big historical festival for the wines of Châteauneuf.

References[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Bailly, Robert (1972). Histoire du vin en Vaucluse. Avignon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bailly, Robert; Bailly, Yolande (1976). Robert Bailly (ed.). Les Châteaux historiques vauclusiens. p. 155.

- Bailly, Robert (1 October 1988). Édisud (ed.). Confréries vigneronnes et ordres bachiques en Provence. Aix-en-Provence. p. 112. ISBN 978-2857443438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Robert Bailly (1986). A. Barthélemy, Avignon (ed.). Dictionnaire des communes de Vaucluse. A. Barthélemy. ISBN 2903044279.* Jules Courtet (1997). Christian Lacour; Nîmes (réed.) (eds.). Dictionnaire géographique, géologique, historique, archéologique et biographique du département de Vaucluse. C. Lacour. ISBN 284406051X.

- Girard, Alain (1997). Édisud (ed.). L'aventure gothique entre Pont-Saint-Esprit et Avignon du XIIIe siècle au XVe siècle. Aix-en-Provence.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lutun, Aude (2001). Flammarion (ed.). Châteauneuf-du-Pape, son terroir, sa dégustation. Paris. ISBN 2082004562.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Histoire de Châteauneuf-du-Pape sur le site avignon-et-provence.com

- ^ Jules Courtet, p. 149

- ^ Robert Bailly, Dictionnaire, p. 154.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Robert Bailly, Dictionnaire op. cit., p. 153

- ^ a b Le château de l'Hers

- ^ a b Jules Courtet, p.147

- ^ Robert Bailly, Dictionnaire, p155

- ^ Jean-Pierre Saltarelli, Il vino p89

- ^ a b c Le château des papes à Châteauneuf-du-Pape[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f Histoire du château de Châteauneuf-du-Pape sur le site 84.com/chateauneuf-pape

- ^ a b c d e Le château des papes à Châteauneuf-du-Pape 1317–1333

- ^ Aude Lutun, p18.

- ^ a b Robert Bailly, Histoire du vin, p60

- ^ a b c Châteauneuf-du-Pape sur le site rhone-medieval.fr

- ^ a b c Robert Bailly, Histoire du vin p62.

- ^ Robert Bailly, Histoire du vin op. cit., p.107.

- ^ Patrick Saletta ed, Haute Provence et Vaucluse – Les Carnets du Patrimoine, Les Guides Masson, Paris, 2000, p234.