Carl Sagan

Carl Sagan | |

|---|---|

Sagan in the 1970s | |

| Born | Carl Edward Sagan November 9, 1934 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | December 20, 1996 (aged 62) Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Resting place | Lake View Cemetery |

| Education | University of Chicago (BA, BS, MS, PhD) |

| Known for | |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5, including Dorion, Nick, and Sasha |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Physical studies of planets (1960) |

| Doctoral advisor | Gerard Kuiper |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Signature | |

Carl Edward Sagan (/ˈseɪɡən/; SAY-gən; November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by exposure to light. He assembled the first physical messages sent into space, the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, which were universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them. He argued in favor of the hypothesis, which has since been accepted, that the high surface temperatures of Venus are the result of the greenhouse effect.[4]

Initially an assistant professor at Harvard, Sagan later moved to Cornell, where he spent most of his career. He published more than 600 scientific papers and articles and was author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books.[5] He wrote many popular science books, such as The Dragons of Eden, Broca's Brain, Pale Blue Dot and The Demon-Haunted World. He also co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television: Cosmos has been seen by at least 500 million people in 60 countries.[6] A book, also called Cosmos, was published to accompany the series. Sagan also wrote a science-fiction novel, published in 1985, called Contact, which became the basis for the 1997 film Contact. His papers, comprising 595,000 items,[7] are archived in the Library of Congress.[8]

Sagan was a popular public advocate of skeptical scientific inquiry and the scientific method; he pioneered the field of exobiology and promoted the search for extra-terrestrial intelligent life (SETI). He spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies. Sagan and his works received numerous awards and honors, including the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal, the National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal, the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction (for his book The Dragons of Eden), and (for Cosmos: A Personal Voyage), two Emmy Awards, the Peabody Award, and the Hugo Award. He married three times and had five children. After developing myelodysplasia, Sagan died of pneumonia at the age of 62 on December 20, 1996.

Early life[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Carl Edward Sagan was born in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of New York City's Brooklyn borough on November 9, 1934.[9][10] His mother, Rachel Molly Gruber, was a housewife from New York City; his father, Samuel Sagan, was a Ukrainian-born garment worker who had emigrated from Kamianets-Podilskyi (then in the Russian Empire).[11] Sagan was named in honor of his maternal grandmother, Chaiya Clara, who had died while giving birth to her second child; she was, in Sagan's words, "the mother she [Rachel] never knew."[12] Sagan's maternal grandfather later married a woman named Rose, whom. Sagan's sister, Carol, would later say, was "never accepted" as Rachel's mother because Rachel "knew she [Rose] wasn't her birth mother."[13] Sagan's family lived in a modest apartment in Bensonhurst. He later described his family as Reform Jews, the most liberal of Judaism's four main branches. He and his sister agreed that their father was not especially religious, but that their mother "definitely believed in God, and was active in the temple [...] and served only kosher meat."[14] During the worst years of the Depression, his father worked as a movie theater usher.[14]

According to biographer Keay Davidson, Sagan experienced a kind of "inner war" as a result of his close relationship with both his parents, who were in many ways "opposites." He traced his analytical inclinations to his mother, who had been extremely poor as a child in New York City during World War I and the 1920s,[15] and whose later intellectual ambitions were sabotaged by her poverty, status as a woman and wife, and Jewish ethnicity. Davidson suggested she "worshipped her only son, Carl" because "he would fulfill her unfulfilled dreams."[15] Sagan believed that he had inherited his sense of wonder from his father, who spent his free time giving apples to the poor or helping soothe tensions between workers and management within New York City's garment industry.[15] Although awed by his son's intellectual abilities, Sagan's father also took his inquisitiveness in stride, viewing it as part of growing up.[15] Later, during his career, Sagan would draw on his childhood memories to illustrate scientific points, as he did in his book Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.[16]

Describing his parents' influence on his later thinking, Sagan said: "My parents were not scientists. They knew almost nothing about science. But in introducing me simultaneously to skepticism and to wonder, they taught me the two uneasily cohabiting modes of thought that are central to the scientific method."[17] He recalled that a defining moment in his development came when his parents took him, at age four, to the 1939 New York World's Fair. He later described his vivid memories of several exhibits there. One, titled America of Tomorrow, included a moving map, which, as he recalled, "showed beautiful highways and cloverleaves and little General Motors cars all carrying people to skyscrapers, buildings with lovely spires, flying buttresses—and it looked great!"[18] Another involved a flashlight shining on a photoelectric cell, which created a crackling sound, and another showed how the sound from a tuning fork became a wave on an oscilloscope. He also saw an exhibit of the then-nascent medium known as television. Remembering it, he later wrote: "Plainly, the world held wonders of a kind I had never guessed. How could a tone become a picture and light become a noise?"[18]

Sagan also saw one of the fair's most publicized events: the burial at Flushing Meadows of a time capsule, which contained mementos from the 1930s to be recovered by Earth's descendants in a future millennium. Davidson wrote that this "thrilled Carl." As an adult, inspired by his memories of the World's Fair, Sagan and his colleagues would create similar time capsules to be sent out into the galaxy: the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record précis.[19]

During World War II, Sagan's parents worried about the fate of their European relatives, but he was generally unaware of the details of the ongoing war. He wrote, "Sure, we had relatives who were caught up in the Holocaust. Hitler was not a popular fellow in our household... but on the other hand, I was fairly insulated from the horrors of the war." His sister, Carol, said that their mother "above all wanted to protect Carl... she had an extraordinarily difficult time dealing with World War II and the Holocaust."[19] Sagan's book The Demon-Haunted World (1996) included his memories of this conflicted period, when his family dealt with the realities of the war in Europe, but tried to prevent it from undermining his optimistic spirit.[17]

Soon after entering elementary school, Sagan began to express his strong inquisitiveness about nature. He recalled taking his first trips to the public library alone, at age five, when his mother got him a library card. He wanted to learn what stars were, since none of his friends or their parents could give him a clear answer: "I went to the librarian and asked for a book about stars [...] and the answer was stunning. It was that the Sun was a star, but really close. The stars were suns, but so far away they were just little points of light. The scale of the universe suddenly opened up to me. It was a kind of religious experience. There was a magnificence to it, a grandeur, a scale which has never left me. Never ever left me."[20] When he was about six or seven, he and a close friend took trips to the American Museum of Natural History, in Manhattan. While there, they visited the Hayden Planetarium and walked around exhibits of space objects, such as meteorites, as well as displays of dinosaur skeletons and naturalistic scenes with animals. As Sagan later wrote, "I was transfixed by the dioramas—lifelike representations of animals and their habitats all over the world. Penguins on the dimly lit Antarctic ice [...] a family of gorillas, the male beating his chest [...] an American grizzly bear standing on his hind legs, ten or twelve feet tall, and staring me right in the eye."[20]

Sagan's parent nurtured his growing interest in science, buying him chemistry sets and reading matter. But his fascination with outer space emerged as his primary focus, especially after he had read science fiction by such writers as H. G. Wells and Edgar Rice Burroughs, stirring his curiosity about the possibility of life on Mars and other planets .[21] According to biographer Ray Spangenburg, Sagan's efforts in his early years to understand the mysteries of the planets became a "driving force in his life, a continual spark to his intellect, and a quest that would never be forgotten."[17] In 1947, Sagan discovered the magazine Astounding Science Fiction, which introduced him to more hard science fiction speculations than those in the Burroughs novels.[21] That same year, mass hysteria developed about the possibility that extraterrestrial visitors had arrived in flying saucers, and the young Sagan joined in the speculation that the flying "discs" people reported seeing in the sky might be alien spaceships.[22]

Education[edit]

Sagan attended David A. Boody Junior High School in his native Bensonhurst and had his bar mitzvah when he turned 13.[23] In 1948, when he was 14, his father's work took the family to the older semi-industrial town of Rahway, New Jersey, where he attended Rahway High School.[23] He was a straight-A student but was bored because his classes did not challenge him and his teachers did not inspire him.[23] His teachers realized this and tried to convince his parents to send him to a private school, with an administrator telling them, "This kid ought to go to a school for gifted children, he has something really remarkable."[24] However, his parents could not afford to do so. Sagan became president of the school's chemistry club, and set up his own laboratory at home. He taught himself about molecules by making cardboard cutouts to help him visualize how they were formed: "I found that about as interesting as doing [chemical] experiments."[24] He was mostly interested in astronomy, learning about it in his spare time. In his junior year of high school, he discovered that professional astronomers were paid for doing something he always enjoyed, and decided on astronomy as a career goal: "That was a splendid day—when I began to suspect that if I tried hard I could do astronomy full-time, not just part-time."[25] Sagan graduated from Rahway High School in 1951.[23]

Before the end of high school, Sagan entered an essay writing contest in which he explored the idea that human contact with advanced life forms from another planet might be as disastrous for people on Earth as Native Americans' first contact with Europeans had been for Native Americans.[26] The subject was considered controversial, but his rhetorical skill won over the judges and they awarded him first prize.[26] When he was about to graduate from high school, his classmates voted him "most likely to succeed" and put him in line to be valedictorian.[26] He attended the University of Chicago because, despite his excellent high school grades, it was one of the very few colleges he had applied to that would consider accepting a 16-year-old. Its chancellor, Robert Maynard Hutchins, had recently retooled the undergraduate College of the University of Chicago into an "ideal meritocracy" built on Great Books, Socratic dialogue, comprehensive examinations, and early entrance to college with no age requirement.[27]

As an honors-program undergraduate, Sagan worked in the laboratory of geneticist H. J. Muller and wrote a thesis on the origins of life with physical chemist Harold Urey. He also joined the Ryerson Astronomical Society.[28] In 1954, he was awarded a Bachelor of Arts with general and special honors[29] in what he quipped was "nothing."[30] In 1955, he earned a Bachelor of Science in physics. He went on to do graduate work at the University of Chicago, earning a Master of Science in physics in 1956 and a Doctor of Philosophy in astronomy and astrophysics in 1960. His doctoral thesis, submitted to the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, was entitled Physical Studies of the Planets.[31][32][33][34] During his graduate studies, he used the summer months to work with planetary scientist Gerard Kuiper, who was his dissertation director,[3] as well as physicist George Gamow and chemist Melvin Calvin. The title of Sagan's dissertation reflected interests he had in common with Kuiper, who had been president of the International Astronomical Union's commission on "Physical Studies of Planets and Satellites" throughout the 1950s.[35]

In 1958, Sagan and Kuiper worked on the classified military Project A119, a secret U.S. Air Force plan to detonate a nuclear warhead on the Moon and document its effects.[36] Sagan had a Top Secret clearance at the Air Force and a Secret clearance with NASA.[37] In 1999, an article published in the journal Nature revealed that Sagan had included the classified titles of two Project A119 papers in his 1959 application for a scholarship to University of California, Berkeley. A follow-up letter to the journal by project leader Leonard Reiffel confirmed Sagan's security leak.[38]

Career and research[edit]

From 1960 to 1962 Sagan was a Miller Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.[40] Meanwhile, he published an article in 1961 in the journal Science on the atmosphere of Venus, while also working with NASA's Mariner 2 team, and served as a "Planetary Sciences Consultant" to the RAND Corporation.[41]

After the publication of Sagan's Science article, in 1961 Harvard University astronomers Fred Whipple and Donald Menzel offered Sagan the opportunity to give a colloquium at Harvard and subsequently offered him a lecturer position at the institution. Sagan instead asked to be made an assistant professor, and eventually Whipple and Menzel were able to convince Harvard to offer Sagan the assistant professor position he requested.[41] Sagan lectured, performed research, and advised graduate students at the institution from 1963 until 1968, as well as working at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, also located in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In 1968, Sagan was denied academic tenure at Harvard. He later indicated that the decision was very unexpected.[42] The denial has been blamed on several factors, including that he focused his interests too broadly across a number of areas (while the norm in academia is to become a renowned expert in a narrow specialty), and perhaps because of his well-publicized scientific advocacy, which some scientists perceived as borrowing the ideas of others for little more than self-promotion.[37] An advisor from his years as an undergraduate student, Harold Urey, wrote a letter to the tenure committee recommending strongly against tenure for Sagan.[22]

Science is more than a body of knowledge; it is a way of thinking. I have a foreboding of an America in my children's or grandchildren's time – when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what's true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness... The dumbing down of America is most evident in the slow decay of substantive content in the enormously influential media, the 30 second sound bites (now down to 10 seconds or less), lowest common denominator programming, credulous presentations on pseudoscience and superstition, but especially a kind of celebration of ignorance.

Carl Sagan, from Demon-Haunted World (1995)[43]

Long before the ill-fated tenure process, Cornell University astronomer Thomas Gold had courted Sagan to move to Ithaca, New York, and join the recently-hired astronomer Frank Drake amongst the faculty at Cornell. Following the denial of tenure from Harvard, Sagan accepted Gold's offer and remained a faculty member at Cornell for nearly 30 years until his death in 1996. Unlike Harvard, the smaller and more laid-back astronomy department at Cornell welcomed Sagan's growing celebrity status.[44] Following two years as an associate professor, Sagan became a full professor at Cornell in 1970 and directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies there. From 1972 to 1981, he was associate director of the Center for Radiophysics and Space Research (CRSR) at Cornell. In 1976, he became the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences, a position he held for the remainder of his life.[45]

Sagan was associated with the U.S. space program from its inception.[citation needed] From the 1950s onward, he worked as an advisor to NASA, where one of his duties included briefing the Apollo astronauts before their flights to the Moon. Sagan contributed to many of the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the Solar System, arranging experiments on many of the expeditions. Sagan assembled the first physical message that was sent into space: a gold-plated plaque, attached to the space probe Pioneer 10, launched in 1972. Pioneer 11, also carrying another copy of the plaque, was launched the following year. He continued to refine his designs; the most elaborate message he helped to develop and assemble was the Voyager Golden Record, which was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977. Sagan often challenged the decisions to fund the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station at the expense of further robotic missions.[46]

Scientific achievements[edit]

Former student David Morrison described Sagan as "an 'idea person' and a master of intuitive physical arguments and 'back of the envelope' calculations",[37] and Gerard Kuiper said that "Some persons work best in specializing on a major program in the laboratory; others are best in liaison between sciences. Dr. Sagan belongs in the latter group."[37]

Sagan's contributions were central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of the planet Venus.[4][47] In the early 1960s no one knew for certain the basic conditions of Venus' surface, and Sagan listed the possibilities in a report later depicted for popularization in a Time Life book Planets. His own view was that Venus was dry and very hot as opposed to the balmy paradise others had imagined. He had investigated radio waves from Venus and concluded that there was a surface temperature of 500 °C (900 °F). As a visiting scientist to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, he contributed to the first Mariner missions to Venus, working on the design and management of the project. Mariner 2 confirmed his conclusions on the surface conditions of Venus in 1962.

Sagan was among[clarification needed] the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan might possess oceans of liquid compounds on its surface and that Jupiter's moon Europa might possess subsurface oceans of water. This would make Europa potentially habitable.[48] Europa's subsurface ocean of water was later indirectly confirmed by the spacecraft Galileo. The mystery of Titan's reddish haze was also solved with Sagan's help. The reddish haze was revealed to be due to complex organic molecules constantly raining down onto Titan's surface.[49]

Sagan further contributed insights regarding the atmospheres of Venus and Jupiter, as well as seasonal changes on Mars. He also perceived global warming as a growing, man-made danger and likened it to the natural development of Venus into a hot, life-hostile planet through a kind of runaway greenhouse effect.[50] He testified to the US Congress in 1985 that the greenhouse effect would change the Earth's climate system.[51] Sagan and his Cornell colleague Edwin Ernest Salpeter speculated about life in Jupiter's clouds, given the planet's dense atmospheric composition rich in organic molecules. He studied the observed color variations on Mars' surface and concluded that they were not seasonal or vegetational changes as most believed,[clarification needed] but shifts in surface dust caused by windstorms.

Sagan is also known for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation.[52][53]

He is also the 1994 recipient of the Public Welfare Medal, the highest award of the National Academy of Sciences for "distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare."[54] He was denied membership in the academy, reportedly because his media activities made him unpopular with many other scientists.[55][56][57]

As of 2017[update], Sagan is the most cited SETI scientist and one of the most cited planetary scientists.[5]

Cosmos: popularizing science on TV[edit]

In 1980 Sagan co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 13-part PBS television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television until 1990. The show has been seen by at least 500 million people across 60 countries.[6][58][59] The book, Cosmos, written by Sagan, was published to accompany the series.[60]

Because of his earlier popularity as a science writer from his best-selling books, including The Dragons of Eden, which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1977, he was asked to write and narrate the show. It was targeted to a general audience of viewers, whom Sagan felt had lost interest in science, partly due to a stifled educational system.[61]

Each of the 13 episodes was created to focus on a particular subject or person, thereby demonstrating the synergy of the universe.[61] They covered a wide range of scientific subjects including the origin of life and a perspective of humans' place on Earth.

The show won an Emmy,[62] along with a Peabody Award, and transformed Sagan from an obscure astronomer into a pop-culture icon.[63] Time magazine ran a cover story about Sagan soon after the show broadcast, referring to him as "creator, chief writer and host-narrator of the show."[64] In 2000, "Cosmos" was released on a remastered set of DVDs.

"Billions and billions"[edit]

After Cosmos aired, Sagan became associated with the catchphrase "billions and billions", although he never actually used the phrase in the Cosmos series.[65] He rather used the term "billions upon billions."[66]

Richard Feynman, a precursor to Sagan, used the phrase "billions and billions" many times in his "red books." However, Sagan's frequent use of the word billions and distinctive delivery emphasizing the "b" (which he did intentionally, in place of more cumbersome alternatives such as "billions with a 'b'", in order to distinguish the word from "millions")[65] made him a favorite target of comic performers, including Johnny Carson,[67][68] Gary Kroeger, Mike Myers, Bronson Pinchot, Penn Jillette, Harry Shearer, and others. Frank Zappa satirized the line in the song "Be in My Video", noting as well "atomic light." Sagan took this all in good humor, and his final book was entitled Billions and Billions, which opened with a tongue-in-cheek discussion of this catchphrase, observing that Carson was an amateur astronomer and that Carson's comic caricature often included real science.[65]

As a humorous tribute to Sagan and his association with the catchphrase "billions and billions", a sagan has been defined as a unit of measurement equivalent to a very large number of anything.[69][70]

Sagan's number[edit]

Sagan's number is the number of stars in the observable universe.[71] This number is reasonably well defined, because it is known what stars are and what the observable universe is, but its value is highly uncertain.

- In 1980, Sagan estimated it to be 10 sextillion in short scale (1022).[72]

- In 2003, it was estimated to be 70 sextillion (7 × 1022).[73][74]

- In 2010, it was estimated to be 300 sextillion (3 × 1023).[75]

Scientific and critical thinking advocacy[edit]

Sagan's ability to convey his ideas allowed many people to understand the cosmos better—simultaneously emphasizing the value and worthiness of the human race, and the relative insignificance of the Earth in comparison to the Universe. He delivered the 1977 series of Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in London.[76]

Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from potential intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms. Sagan was so persuasive that by 1982 he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science, signed by 70 scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners. This signaled a tremendous increase in the respectability of a then-controversial field. Sagan also helped Frank Drake write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the Arecibo radio telescope on November 16, 1974, aimed at informing potential extraterrestrials about Earth.

Sagan was chief technology officer of the professional planetary research journal Icarus for 12 years. He co-founded The Planetary Society and was a member of the SETI Institute Board of Trustees. Sagan served as Chairman of the Division for Planetary Science of the American Astronomical Society, as President of the Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union, and as Chairman of the Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

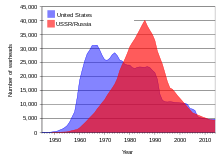

At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in nuclear disarmament efforts by promoting hypotheses on the effects of nuclear war, when Paul Crutzen's "Twilight at Noon" concept suggested that a substantial nuclear exchange could trigger a nuclear twilight and upset the delicate balance of life on Earth by cooling the surface. In 1983 he was one of five authors—the "S"—in the follow-up "TTAPS" model (as the research article came to be known), which contained the first use of the term "nuclear winter", which his colleague Richard P. Turco had coined.[77] In 1984 he co-authored the book The Cold and the Dark: The World after Nuclear War and in 1990 the book A Path Where No Man Thought: Nuclear Winter and the End of the Arms Race, which explains the nuclear-winter hypothesis and advocates nuclear disarmament. Sagan received a great deal of skepticism and disdain for the use of media to disseminate a very uncertain hypothesis. A personal correspondence with nuclear physicist Edward Teller around 1983 began amicably, with Teller expressing support for continued research to ascertain the credibility of the winter hypothesis. However, Sagan and Teller's correspondence would ultimately result in Teller writing: "A propagandist is one who uses incomplete information to produce maximum persuasion. I can compliment you on being, indeed, an excellent propagandist, remembering that a propagandist is the better the less he appears to be one."[78] Biographers of Sagan would also comment that from a scientific viewpoint, nuclear winter was a low point for Sagan, although, politically speaking, it popularized his image amongst the public.[78]

The adult Sagan remained a fan of science fiction, although disliking stories that were not realistic (such as ignoring the inverse-square law) or, he said, did not include "thoughtful pursuit of alternative futures."[21] He wrote books to popularize science, such as Cosmos, which reflected and expanded upon some of the themes of A Personal Voyage and became the best-selling science book ever published in English;[79] The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, which won a Pulitzer Prize; and Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science. Sagan also wrote the best-selling science fiction novel Contact in 1985, based on a film treatment he wrote with his wife, Ann Druyan, in 1979, but he did not live to see the book's 1997 motion-picture adaptation, which starred Jodie Foster and won the 1998 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.

On it, everyone you ever heard of... The aggregate of all our joys and sufferings, thousands of confident religions, ideologies and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilizations, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every hopeful child, every mother and father, every inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species, lived there on a mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam. ...

Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Carl Sagan, Cornell lecture in 1994

Sagan wrote a sequel to Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by The New York Times. He appeared on PBS's Charlie Rose program in January 1995.[46] Sagan also wrote the introduction for Stephen Hawking's bestseller A Brief History of Time. Sagan was also known for his popularization of science, his efforts to increase scientific understanding among the general public, and his positions in favor of scientific skepticism and against pseudoscience, such as his debunking of the Betty and Barney Hill abduction. To mark the tenth anniversary of Sagan's death, David Morrison, a former student of Sagan, recalled "Sagan's immense contributions to planetary research, the public understanding of science, and the skeptical movement" in Skeptical Inquirer.[37]

Following Saddam Hussein's threats to light Kuwait's oil wells on fire in response to any physical challenge to Iraqi control of the oil assets, Sagan together with his "TTAPS" colleagues and Paul Crutzen, warned in January 1991 in The Baltimore Sun and Wilmington Morning Star newspapers that if the fires were left to burn over a period of several months, enough smoke from the 600 or so 1991 Kuwaiti oil fires "might get so high as to disrupt agriculture in much of South Asia ..." and that this possibility should "affect the war plans";[82][83] these claims were also the subject of a televised debate between Sagan and physicist Fred Singer on January 22, aired on the ABC News program Nightline.[84][85]

In the televised debate, Sagan argued that the effects of the smoke would be similar to the effects of a nuclear winter, with Singer arguing to the contrary. After the debate, the fires burnt for many months before extinguishing efforts were complete. The results of the smoke did not produce continental-sized cooling. Sagan later conceded in The Demon-Haunted World that the prediction did not turn out to be correct: "it was pitch black at noon and temperatures dropped 4–6 °C over the Persian Gulf, but not much smoke reached stratospheric altitudes and Asia was spared."[86]

In his later years, Sagan advocated the creation of an organized search for asteroids/near-Earth objects (NEOs) that might impact the Earth but to forestall or postpone developing the technological methods that would be needed to defend against them.[87] He argued that all of the numerous methods proposed to alter the orbit of an asteroid, including the employment of nuclear detonations, created a deflection dilemma: if the ability to deflect an asteroid away from the Earth exists, then one would also have the ability to divert a non-threatening object towards Earth, creating an immensely destructive weapon.[88][89] In a 1994 paper he co-authored, he ridiculed a 3-day long "Near-Earth Object Interception Workshop" held by Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in 1993 that did not, "even in passing" state that such interception and deflection technologies could have these "ancillary dangers."[88]

Sagan remained hopeful that the natural NEO impact threat and the intrinsically double-edged essence of the methods to prevent these threats would serve as a "new and potent motivation to maturing international relations."[88][90] Later acknowledging that, with sufficient international oversight, in the future a "work our way up" approach to implementing nuclear explosive deflection methods could be fielded, and when sufficient knowledge was gained, to use them to aid in mining asteroids.[89] His interest in the use of nuclear detonations in space grew out of his work in 1958 for the Armour Research Foundation's Project A119, concerning the possibility of detonating a nuclear device on the lunar surface.[91]

Sagan was a critic of Plato, having said of the ancient Greek philosopher: "Science and mathematics were to be removed from the hands of the merchants and the artisans. This tendency found its most effective advocate in a follower of Pythagoras named Plato" and[92]

He (Plato) believed that ideas were far more real than the natural world. He advised the astronomers not to waste their time observing the stars and planets. It was better, he believed, just to think about them. Plato expressed hostility to observation and experiment. He taught contempt for the real world and disdain for the practical application of scientific knowledge. Plato's followers succeeded in extinguishing the light of science and experiment that had been kindled by Democritus and the other Ionians.

In 1995 (as part of his book The Demon-Haunted World), Sagan popularized a set of tools for skeptical thinking called the "baloney detection kit", a phrase first coined by Arthur Felberbaum, a friend of his wife Ann Druyan.[93]

Popularizing science[edit]

Speaking about his activities in popularizing science, Sagan said that there were at least two reasons for scientists to share the purposes of science and its contemporary state. Simple self-interest was one: much of the funding for science came from the public, and the public therefore had the right to know how the money was being spent. If scientists increased public admiration for science, there was a good chance of having more public supporters.[94] The other reason was the excitement of communicating one's own excitement about science to others.[10]

Following the success of Cosmos, Sagan set up his own publishing firm, Cosmos Store, to publish science books for the general public. It was not successful.[95]

Criticisms[edit]

While Sagan was widely adored by the general public, his reputation in the scientific community was more polarized.[96] Critics sometimes characterized his work as fanciful, non-rigorous, and self-aggrandizing,[97] and others complained in his later years that he neglected his role as a faculty member to foster his celebrity status.[98]

One of Sagan's harshest critics, Harold Urey, felt that Sagan was getting too much publicity for a scientist and was treating some scientific theories too casually.[99] Urey and Sagan were said to have different philosophies of science, according to Davidson. While Urey was an "old-time empiricist" who avoided theorizing about the unknown, Sagan was by contrast willing to speculate openly about such matters.[42] Fred Whipple wanted Harvard to keep Sagan there, but learned that because Urey was a Nobel laureate, his opinion was an important factor in Harvard denying Sagan tenure.[99]

Sagan's Harvard friend Lester Grinspoon also stated: "I know Harvard well enough to know there are people there who certainly do not like people who are outspoken."[99] Grinspoon added:[99]

Wherever you turned, there was one astronomer being quoted on everything, one astronomer whose face you were seeing on TV, and one astronomer whose books had the preferred display slot at the local bookstore.

Some, like Urey, later came to realize that Sagan's popular brand of scientific advocacy was beneficial to the science as a whole.[100] Urey especially liked Sagan's 1977 book The Dragons of Eden and wrote Sagan with his opinion: "I like it very much and am amazed that someone like you has such an intimate knowledge of the various features of the problem... I congratulate you... You are a man of many talents."[100]

Sagan was accused of borrowing some ideas of others for his own benefit and countered these claims by explaining that the misappropriation was an unfortunate side effect of his role as a science communicator and explainer, and that he attempted to give proper credit whenever possible.[99]

Social concerns[edit]

Sagan believed that the Drake equation, on substitution of reasonable estimates, suggested that a large number of extraterrestrial civilizations would form, but that the lack of evidence of such civilizations highlighted by the Fermi paradox suggests technological civilizations tend to self-destruct. This stimulated his interest in identifying and publicizing ways that humanity could destroy itself, with the hope of avoiding such a cataclysm and eventually becoming a spacefaring species. Sagan's deep concern regarding the potential destruction of human civilization in a nuclear holocaust was conveyed in a memorable cinematic sequence in the final episode of Cosmos, called "Who Speaks for Earth?" Sagan had already resigned[date missing] from the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board's UFO-investigating Condon Committee and voluntarily surrendered his top-secret clearance in protest over the Vietnam War.[101] Following his marriage to his third wife (novelist Ann Druyan) in June 1981, Sagan became more politically active—particularly in opposing escalation of the nuclear arms race under President Ronald Reagan.

In March 1983, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative—a multibillion-dollar project to develop a comprehensive defense against attack by nuclear missiles, which was quickly dubbed the "Star Wars" program. Sagan spoke out against the project, arguing that it was technically impossible to develop a system with the level of perfection required, and far more expensive to build such a system than it would be for an enemy to defeat it through decoys and other means—and that its construction would seriously destabilize the "nuclear balance" between the United States and the Soviet Union, making further progress toward nuclear disarmament impossible.[102]

When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev declared a unilateral moratorium on the testing of nuclear weapons, which would begin on August 6, 1985—the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima—the Reagan administration dismissed the dramatic move as nothing more than propaganda and refused to follow suit. In response, US anti-nuclear and peace activists staged a series of protest actions at the Nevada Test Site, beginning on Easter Sunday in 1986 and continuing through 1987. Hundreds of people in the "Nevada Desert Experience" group were arrested, including Sagan, who was arrested on two separate occasions as he climbed over a chain-link fence at the test site during the underground Operation Charioteer and United States's Musketeer nuclear test series of detonations.[103]

Sagan was also a vocal advocate of the controversial notion of testosterone poisoning, arguing in 1992 that human males could become gripped by an "unusually severe [case of] testosterone poisoning" and this could compel them to become genocidal.[104] In his review of Moondance magazine writer Daniela Gioseffi's 1990 book Women on War, he argues that females are the only half of humanity "untainted by testosterone poisoning."[105] One chapter of his 1993 book Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is dedicated to testosterone and its alleged poisonous effects.[106]

In 1989, Carl Sagan was interviewed by Ted Turner whether he believed in socialism and responded that: "I'm not sure what a socialist is. But I believe the government has a responsibility to care for the people... I'm talking about making the people self-reliant."[107]

Personal life and beliefs[edit]

Sagan was married three times. In 1957, he married biologist Lynn Margulis. The couple had two children, Jeremy and Dorion Sagan; their marriage ended in 1964. Sagan married artist Linda Salzman in 1968 and they had a child together, Nick Sagan, and divorced in 1981. During these marriages, Carl Sagan focused heavily on his career, a factor which may have contributed to Sagan's first divorce.[37] In 1981, Sagan married author Ann Druyan and they later had two children, Alexandra (known as Sasha) and Samuel Sagan. Carl Sagan and Druyan remained married until his death in 1996.

While teaching at Cornell, he lived in an Egyptian revival house in Ithaca perched on the edge of a cliff that had formerly been the headquarters of a Cornell secret society.[108] While there he drove a red Porsche 911 Targa and an orange 1970 Porsche 914[109] with the license plate PHOBOS.

In 1994, engineers at Apple Computer code-named the Power Macintosh 7100 "Carl Sagan" in the hope that Apple would make "billions and billions" with the sale of the PowerMac 7100.[9] The name was only used internally, but Sagan was concerned that it would become a product endorsement and sent Apple a cease-and-desist letter. Apple complied, but engineers retaliated by changing the internal codename to "BHA" for "Butt-Head Astronomer."[110][111] In November 1995, after further legal battle, an out-of-court settlement was reached and Apple's office of trademarks and patents released a conciliatory statement that "Apple has always had great respect for Dr. Sagan. It was never Apple's intention to cause Dr. Sagan or his family any embarrassment or concern."[112]

In 2019, Carl Sagan's daughter Sasha Sagan released For Small Creatures Such as We: Rituals for Finding Meaning in our Unlikely World, which depicts life with her parents and her father's death when she was fourteen.[113] Building on a theme in her father's work, Sasha Sagan argues in For Small Creatures Such as We that skepticism does not imply pessimism.[114]

I have just finished The Cosmic Connection and loved every word of it. You are my idea of a good writer because you have an unmannered style, and when I read what you write, I hear you talking. One thing about the book made me nervous. It was entirely too obvious that you are smarter than I am. I hate that.

Isaac Asimov, in a letter to Sagan, 1973[115]

Sagan was acquainted with science fiction fandom through his friendship with Isaac Asimov, and he spoke at the Nebula Awards ceremony in 1969.[116][117] Asimov described Sagan as one of only two people he ever met whose intellect surpassed his own, the other being computer scientist and artificial intelligence expert Marvin Minsky.[118]

Naturalism[edit]

Sagan wrote frequently about religion and the relationship between religion and science, expressing his skepticism about the conventional conceptualization of God as a sapient being. For example:

Some people think God is an outsized, light-skinned male with a long white beard, sitting on a throne somewhere up there in the sky, busily tallying the fall of every sparrow. Others—for example Baruch Spinoza and Albert Einstein—considered God to be essentially the sum total of the physical laws which describe the universe. I do not know of any compelling evidence for anthropomorphic patriarchs controlling human destiny from some hidden celestial vantage point, but it would be madness to deny the existence of physical laws.[119]

In another description of his view on the concept of God, Sagan wrote:

The idea that God is an oversized white male with a flowing beard who sits in the sky and tallies the fall of every sparrow is ludicrous. But if by God one means the set of physical laws that govern the universe, then clearly there is such a God. This God is emotionally unsatisfying ... it does not make much sense to pray to the law of gravity.[120]

On atheism, Sagan commented in 1981:

An atheist is someone who is certain that God does not exist, someone who has compelling evidence against the existence of God. I know of no such compelling evidence. Because God can be relegated to remote times and places and to ultimate causes, we would have to know a great deal more about the universe than we do now to be sure that no such God exists. To be certain of the existence of God and to be certain of the nonexistence of God seem to me to be the confident extremes in a subject so riddled with doubt and uncertainty as to inspire very little confidence indeed.[121]

Sagan also commented on Christianity and the Jefferson Bible, stating "My long-time view about Christianity is that it represents an amalgam of two seemingly immiscible parts, the religion of Jesus and the religion of Paul. Thomas Jefferson attempted to excise the Pauline parts of the New Testament. There wasn't much left when he was done, but it was an inspiring document."[122]

Sagan thought that spirituality should be scientifically informed and that traditional religions should be abandoned and replaced with belief systems that revolve around the scientific method,[123] but also the mystery and incompleteness of scientific fields. Regarding spirituality and its relationship with science, Sagan stated:

'Spirit' comes from the Latin word 'to breathe'. What we breathe is air, which is certainly matter, however thin. Despite usage to the contrary, there is no necessary implication in the word 'spiritual' that we are talking of anything other than matter (including the matter of which the brain is made), or anything outside the realm of science. On occasion, I will feel free to use the word. Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light-years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual.[124]

An environmental appeal, "Preserving and Cherishing the Earth", primarily written by Sagan and signed by him and other noted scientists as well as religious leaders, and published in January 1990, stated that "The historical record makes clear that religious teaching, example, and leadership are powerfully able to influence personal conduct and commitment... Thus, there is a vital role for religion and science."[125]

In reply to a question in 1996 about his religious beliefs, Sagan answered, "I'm agnostic."[126] Sagan maintained that the idea of a creator God of the Universe was difficult to prove or disprove and that the only conceivable scientific discovery that could challenge it would be an infinitely old universe.[127] His son, Dorion Sagan said, "My father believed in the God of Spinoza and Einstein, God not behind nature but as nature, equivalent to it."[128] His last wife, Ann Druyan, stated:

When my husband died, because he was so famous and known for not being a believer, many people would come up to me—it still sometimes happens—and ask me if Carl changed at the end and converted to a belief in an afterlife. They also frequently ask me if I think I will see him again. Carl faced his death with unflagging courage and never sought refuge in illusions. The tragedy was that we knew we would never see each other again. I don't ever expect to be reunited with Carl.[129]

In 2006, Ann Druyan edited Sagan's 1985 Glasgow Gifford Lectures in Natural Theology into a book, The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God, in which he elaborates on his views of divinity in the natural world.

Sagan is also widely regarded as a freethinker or skeptic; one of his most famous quotations, in Cosmos, was, "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence"[130] (called the "Sagan standard" by some[131]). This was based on a nearly identical statement by fellow founder of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, Marcello Truzzi, "An extraordinary claim requires extraordinary proof."[132][133] This idea had been earlier aphorized in Théodore Flournoy's work From India to the Planet Mars (1899) from a longer quote by Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827), a French mathematician and astronomer, as the Principle of Laplace: "The weight of the evidence should be proportioned to the strangeness of the facts."[134]

Late in his life, Sagan's books elaborated on his naturalistic view of the world. In The Demon-Haunted World, he presented tools for testing arguments and detecting fallacious or fraudulent ones, essentially advocating the wide use of critical thinking and of the scientific method. The compilation Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium, published in 1997 after Sagan's death, contains essays written by him, on topics such as his views on abortion, and also an essay by his widow, Ann Druyan, about the relationship between his agnostic and freethinking beliefs and his death.

Sagan warned against humans' tendency towards anthropocentrism. He was the faculty adviser for the Cornell Students for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. In the Cosmos chapter "Blues For a Red Planet", Sagan wrote, "If there is life on Mars, I believe we should do nothing with Mars. Mars then belongs to the Martians, even if the Martians are only microbes."[135]

Marijuana advocacy[edit]

Sagan was a user and advocate of marijuana. Under the pseudonym "Mr. X", he contributed an essay about smoking cannabis to the 1971 book Marihuana Reconsidered.[136][137] The essay explained that marijuana use had helped to inspire some of Sagan's works and enhance sensual and intellectual experiences. After Sagan's death, his friend Lester Grinspoon disclosed this information to Sagan's biographer, Keay Davidson. The publishing of the biography Carl Sagan: A Life, in 1999 brought media attention to this aspect of Sagan's life.[138][139][140] Not long after his death, his widow Ann Druyan went on to preside over the board of directors of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), a non-profit organization dedicated to reforming cannabis laws.[141][142]

UFOs[edit]

In 1947, the year that inaugurated the "flying saucer" craze, the young Sagan suspected the "discs" might be alien spaceships.[22]

Sagan's interest in UFO reports prompted him on August 3, 1952, to write a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson to ask how the United States would respond if flying saucers turned out to be extraterrestrial.[143] He later had several conversations on the subject in 1964 with Jacques Vallée.[144] Though quite skeptical of any extraordinary answer to the UFO question, Sagan thought scientists should study the phenomenon, at least because there was widespread public interest in UFO reports.

Stuart Appelle notes that Sagan "wrote frequently on what he perceived as the logical and empirical fallacies regarding UFOs and the abduction experience. Sagan rejected an extraterrestrial explanation for the phenomenon but felt there were both empirical and pedagogical benefits for examining UFO reports and that the subject was, therefore, a legitimate topic of study."[145]

In 1966, Sagan was a member of the Ad Hoc Committee to Review Project Blue Book, the U.S. Air Force's UFO investigation project. The committee concluded Blue Book had been lacking as a scientific study, and recommended a university-based project to give the UFO phenomenon closer scientific scrutiny. The result was the Condon Committee (1966–68), led by physicist Edward Condon, and in their final report they formally concluded that UFOs, regardless of what any of them actually were, did not behave in a manner consistent with a threat to national security.

Sociologist Ron Westrum writes that "The high point of Sagan's treatment of the UFO question was the AAAS' symposium in 1969. A wide range of educated opinions on the subject were offered by participants, including not only proponents such as James McDonald and J. Allen Hynek but also skeptics like astronomers William Hartmann and Donald Menzel. The roster of speakers was balanced, and it is to Sagan's credit that this event was presented in spite of pressure from Edward Condon."[144] With physicist Thornton Page, Sagan edited the lectures and discussions given at the symposium; these were published in 1972 as UFO's: A Scientific Debate. Some of Sagan's many books examine UFOs (as did one episode of Cosmos) and he claimed a religious undercurrent to the phenomenon.

Sagan again revealed his views on interstellar travel in his 1980 Cosmos series. In one of his last written works, Sagan argued that the chances of extraterrestrial spacecraft visiting Earth are vanishingly small. However, Sagan did think it plausible that Cold War concerns contributed to governments misleading their citizens about UFOs, and wrote that "some UFO reports and analyses, and perhaps voluminous files, have been made inaccessible to the public which pays the bills ... It's time for the files to be declassified and made generally available." He cautioned against jumping to conclusions about suppressed UFO data and stressed that there was no strong evidence that aliens were visiting the Earth either in the past or present.[146]

Sagan briefly served as an adviser on Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey.[147] Sagan proposed that the film suggest, rather than depict, extraterrestrial superintelligence.[148]

Sagan's paradox[edit]

Sagan's contribution to the 1969 AAAS symposium was an attack on the belief that UFOs are piloted by extraterrestrial beings. Using the Drake equation and applying several logical assumptions, Sagan calculated the possible number of advanced civilizations capable of interstellar travel to be about one million. He projected that any civilization wishing to check on all the others on a regular basis of, say, once a year would have to launch 10,000 spacecraft annually. Not only does that seem like an unreasonable number of launchings, but it would take all the material in one percent of the universe's stars to produce all the spaceships needed for all the civilizations to seek each other out.

To argue that the Earth was being chosen for regular visitations, Sagan said, one would have to assume that the planet is somehow unique, and that assumption "goes exactly against the idea that there are lots of civilizations around. Because if there are then our sort of civilization must be pretty common. And if we're not pretty common then there aren't going to be many civilizations advanced enough to send visitors."

This argument, which some called Sagan's paradox, helped to establish a new school of thought, namely the belief that extraterrestrial life exists but has nothing to do with UFOs. The new belief had a salutary effect on UFO studies. It gave scientists opportunities to search the universe for intelligent life unencumbered by the stigma associated with UFOs.[149]

Death[edit]

After suffering from myelodysplasia for two years and receiving three bone marrow transplants from his sister, Sagan died from pneumonia at the age of 62 at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle on December 20, 1996.[10][150] He was buried at Lake View Cemetery in Ithaca, New York.

Awards and honors[edit]

- Annual Award for Television Excellence—1981—Ohio State University—PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage

- Apollo Achievement Award—National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal—National Aeronautics and Space Administration (1977)

- Emmy—Outstanding Individual Achievement—1981—PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage[62]

- Emmy—Outstanding Informational Series—1981—PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage[62]

- Fellow of the American Physical Society–1989[151]

- Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal—National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- Helen Caldicott Leadership Award – Awarded by Women's Action for Nuclear Disarmament

- Hugo Award—1981—Best Dramatic Presentation—Cosmos: A Personal Voyage

- Hugo Award—1981—Best Related Non-Fiction Book—Cosmos

- Hugo Award—1998—Best Dramatic Presentation—Contact

- Humanist of the Year—1981—Awarded by the American Humanist Association[152]

- American Philosophical Society—1995—Elected to membership.[153]

- In Praise of Reason Award—1987—Committee for Skeptical Inquiry[154]

- Isaac Asimov Award—1994—Committee for Skeptical Inquiry[155]

- John F. Kennedy Astronautics Award—1982—American Astronautical Society[156]

- Special non-fiction Campbell Memorial Award—1974—The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective[157]

- Joseph Priestley Award—"For distinguished contributions to the welfare of mankind"[158]

- Klumpke-Roberts Award of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific—1974

- Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement—1975[159]

- Konstantin Tsiolkovsky Medal—Awarded by the Soviet Cosmonauts Federation

- Locus Award 1986—Contact

- Lowell Thomas Award—The Explorers Club—75th Anniversary

- Masursky Award—American Astronomical Society

- Miller Research Fellowship—Miller Institute (1960–1962)

- Oersted Medal—1990—American Association of Physics Teachers

- Peabody Award—1980—PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage

- Le Prix Galabert d'astronautique—International Astronautical Federation (IAF)[160]

- Public Welfare Medal—1994—National Academy of Sciences[161]

- Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction—1978—The Dragons of Eden

- Science Fiction Chronicle Award—1998—Dramatic Presentation—Contact

- UCLA Medal–1991[162]

- Inductee to International Space Hall of Fame in 2004[163]

- Named the "99th Greatest American" on June 5, 2005, Greatest American television series on the Discovery Channel[164]

- Named an honorary member of the Demosthenian Literary Society on November 10, 2011

- New Jersey Hall of Fame—2009—Inductee.[165]

- Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) Pantheon of Skeptics—April 2011—Inductee[a][167]

- Grand-Cross of the Order of Saint James of the Sword, Portugal (November 23, 1998)[168]

- Honorary Doctor of Science (Sc.D.) degree from Whittier College in 1978.[169]

Posthumous recognition[edit]

The 1997 film Contact was based on the only novel Sagan wrote[170] and finished after his death. It ends with the dedication "For Carl." His photo can also be seen in the film.

In 1997, the Sagan Planet Walk was opened in Ithaca, New York. It is a walking-scale model of the Solar System, extending 1.2 km from the center of The Commons in downtown Ithaca to the Sciencenter, a hands-on museum. The exhibition was created in memory of Carl Sagan, who was an Ithaca resident and Cornell Professor. Professor Sagan had been a founding member of the museum's advisory board.[171]

The landing site of the uncrewed Mars Pathfinder spacecraft was renamed the Carl Sagan Memorial Station on July 5, 1997.

Asteroid 2709 Sagan is named in his honor,[93] as is the Carl Sagan Institute for the search of habitable planets.

Sagan's son, Nick Sagan, wrote several episodes in the Star Trek franchise. In an episode of Star Trek: Enterprise entitled "Terra Prime", a quick shot is shown of the relic rover Sojourner, part of the Mars Pathfinder mission, placed by a historical marker at Carl Sagan Memorial Station on the Martian surface. The marker displays a quote from Sagan: "Whatever the reason you're on Mars, I'm glad you're there, and I wish I was with you." Sagan's student Steve Squyres led the team that landed the rovers Spirit and Opportunity successfully on Mars in 2004.

On November 9, 2001, on what would have been Sagan's 67th birthday, the Ames Research Center dedicated the site for the Carl Sagan Center for the Study of Life in the Cosmos. "Carl was an incredible visionary, and now his legacy can be preserved and advanced by a 21st century research and education laboratory committed to enhancing our understanding of life in the universe and furthering the cause of space exploration for all time", said NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin. Ann Druyan was at the center as it opened its doors on October 22, 2006.

Sagan has at least three awards named in his honor:

- The Carl Sagan Memorial Award presented jointly since 1997 by the American Astronomical Society and The Planetary Society,

- The Carl Sagan Medal for Excellence in Public Communication in Planetary Science presented since 1998 by the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences (AAS/DPS) for outstanding communication by an active planetary scientist to the general public—Carl Sagan was one of the original organizing committee members of the DPS, and

- The Carl Sagan Award for Public Understanding of Science presented by the Council of Scientific Society presidents (CSSP)—Sagan was the first recipient of the CSSP award in 1993.[172]

August 2007 the Independent Investigations Group (IIG) awarded Sagan posthumously a Lifetime Achievement Award. This honor has also been awarded to Harry Houdini and James Randi.[173]

In September 2008, a musical compositor Benn Jordan released his album Pale Blue Dot as a tribute to Carl Sagan's life.[174][175]

Beginning in 2009, a musical project known as Symphony of Science sampled several excerpts of Sagan from his series Cosmos and remixed them to electronic music. To date, the videos have received over 21 million views worldwide on YouTube.[176]

The 2014 Swedish science fiction short film Wanderers uses excerpts of Sagan's narration in 1994 of his book Pale Blue Dot, played over digitally-created visuals of humanity's possible future expansion into outer space.[177][178]

In February 2015, the Finnish-based symphonic metal band Nightwish released the song "Sagan" as a non-album bonus track for their single "Élan."[179] The song, written by the band's songwriter/composer/keyboardist Tuomas Holopainen, is an homage to the life and work of the late Carl Sagan.

In August 2015, it was announced that a biopic of Sagan's life was being planned by Warner Bros.[180]

On October 21, 2019, the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Theater was opened at the Center for Inquiry West in Los Angeles.[181]

In 2022, Sagan was posthumously awarded the Future of Life Award "for reducing the risk of nuclear war by developing and popularizing the science of nuclear winter." The honor, shared by seven other recipients involved in nuclear winter research, was accepted by his widow, Ann Druyan.[182]

In 2022, the audiobook recording of Sagan's 1994 book Pale Blue Dot was selected by the U.S. Library of Congress for inclusion in the National Recording Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[183][184]

In 2023, a movie Voyagers by Sebastián Lelio was announced with Sagan played by Andrew Garfield and with Daisy Edgar-Jones playing Sagan's third wife, Ann Druyan.[185]

Books[edit]

- Sagan, Carl (1961). Organic Matter and The Moon. Panel on Extra-Terrestrial Life for the Armed Forces – NRC Committee on Bio-Astronautics, Publication 757. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences—National Research Council. LCCN 61-60064.

- Sagan, Carl; Leonard, Jonathan Norton (1966). Planets. Life Science Library. Editors of Life. New York: Time Inc. LCCN 66022436. OCLC 346361.

- ——; Shklovskii, I.S. (1966) [Originally published 1962 as Вселенная, жизнь, разум; Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences Publisher]. Intelligent Life in the Universe. Authorized translation by Paula Fern. San Francisco: Holden-Day, Inc. LCCN 64018404. OCLC 317314.

- ——; Page, Thornton, eds. (1972). UFO's: A Scientific Debate. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-40740-6. LCCN 72004572. OCLC 415373.

- ——, ed. (1973). Communication with Extraterrestrial Intelligence (CETI). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-19106-7. LCCN 73013999. OCLC 700752.

- ——; Bradbury, Ray; Clarke, Arthur C.; et al. (1973). Mars and the Mind of Man (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-060-10443-6. LCCN 72009746. OCLC 613541.

- —— (1973). The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective. Produced by Jerome Agel (1st ed.). Garden City, NY: Anchor Press. ISBN 978-0-385-00457-2. LCCN 73081117. OCLC 756158.

- —— (1975). Other Worlds. Produced by Jerome Agel. Toronto, NY: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-552-66439-4. OCLC 3029556.

- —— (1977). The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-41045-6. LCCN 76053472. OCLC 2922889.

- ——; Drake, F. D.; Lomberg, Jon; et al. (1978). Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record (1st ed.). New York: Random House. Bibcode:1978mevi.book.....S. ISBN 978-0-394-41047-0. LCCN 77005991. OCLC 4037611.

- —— (1979). Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-50169-7. LCCN 78021810. OCLC 4493944.

- —— (1980). Cosmos (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-50294-6. LCCN 80005286. OCLC 6280573.

- ——; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Kennedy, Donald; et al. (1984). The Cold and the Dark: The World after Nuclear War: The Conference on the Long-Term Worldwide Biological Consequences of Nuclear War. Foreword by Lewis Thomas (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-01870-7. LCCN 84006070. OCLC 10697281.

- ——; Druyan, Ann (1985). Comet (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-54908-8. LCCN 85008308. OCLC 811602694.

- —— (1985). Contact: A Novel. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-43400-7. LCCN 85014645. OCLC 12344811.

- ——; Turco, Richard (1990). A Path Where No Man Thought: Nuclear Winter and the End of the Arms Race (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-58307-5. LCCN 89043155. OCLC 20217496.

- ——; Druyan, Ann (1992). Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors: A Search for Who We Are (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-53481-7. LCCN 92050155. OCLC 25675747.

- Sagan, Carl; Thompson, W. Reid; Carlson, Robert; Gurnett, Donald; Hord, Charles (October 23, 1993). "A search for life on Earth from the Galileo spacecraft" (PDF). Nature. 365 (6448): 715–721. Bibcode:1993Natur.365..715S. doi:10.1038/365715a0. PMID 11536539. S2CID 4269717.

- Sagan, Carl; Turco, Richard P. (November 1993). "Nuclear Winter in the Post-Cold War Era" (PDF). Journal of Peace Research. 30 (4): 369–373. doi:10.1177/0022343393030004001. JSTOR 424481. S2CID 109843259. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2020.

- —— (1994). Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-43841-0. LCCN 94018121. OCLC 30736355.

- —— (1995). The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-53512-8. LCCN 95034076. OCLC 779687822. (Note: errata slip inserted.)

- ——; Druyan, Ann (1997). Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-41160-4. LCCN 96052730. OCLC 36066119.

- —— (2006) [Edited from 1985 Gifford Lectures, University of Glasgow]. Druyan, Ann (ed.). The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-107-3. LCCN 2006044827. OCLC 69021064.

See also[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Terzian & Trimble 1997, Article in Bull AAS 29(4).

- ^ Davidson 1999, The book is dedicated to Pollack.

- ^ a b Carl Sagan at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ a b Sagan, Carl; Head, Tom (2006). Conversations with Carl Sagan (illustrated ed.). University Press of Mississippi. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-57806-736-7. Extract of page 14 Archived December 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Carl Sagan". scholar.google.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ a b "StarChild: Dr. Carl Sagan". StarChild. NASA. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ The Seth MacFarlane Collection of the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive: A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress (PDF). Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Lowensohn, Josh (February 4, 2014). "Massive Carl Sagan archive posted by Library of Congress". The Verge. Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Poundstone 1999, pp. 363–364, 374–375.

- ^ a b c Dicke, William (December 21, 1996). "Carl Sagan, an Astronomer Who Excelled at Popularizing Science, Is Dead at 62". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ "Carl Sagan". Internet Accuracy Project. Grandville, MI. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Davidson 1999.

- ^ "Carl Sagan". archive.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Davidson 1999, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Davidson 1999, p. 2.

- ^ Davidson 1999, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Spangenburg & Moser 2004, pp. 2–5.

- ^ a b Davidson 1999, p. 14.

- ^ a b Davidson 1999, p. 15.

- ^ a b Davidson 1999, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Sagan, Carl (May 28, 1978). "Growing up with Science Fiction". The New York Times. p. SM7. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c Davidson, Keay (2000). "Sagan, Carl (1934–1996), space scientist, author, science popularizer, TV personality, and antinuclear weapons activist". American National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1302612. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Davidson 1999, p. 23.

- ^ a b Davidson 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Davidson 1999, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Poundstone 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Poundstone 1999, p. 14.

- ^ "Ryerson Astronomical Society". Ryerson Astronomical Society (RAS). University of Chicago Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Carl Sagan - website of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ^ Sic. See Spangenburg, Ray; Moser, Kit; Moser, Diane (2004). Carl Sagan: A Biography (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-313-32265-5. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2018. Extract of page 28 Archived December 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1960). Physical Studies of the Planets (PhD thesis). University of Chicago. p. ii. OCLC 20678107. ProQuest 301918122.

A thesis in four parts submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Astronomy, University of Chicago, June, 1960

- ^ "Graduate students receive first Sagan teaching awards". University of Chicago Chronicle. 13 (6). November 11, 1993. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ Head 2006, p. xxi.

- ^ Spangenburg & Moser 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Tatarewicz, Joseph N. (1990), Space Technology & Planetary Astronomy, Science, technology, and society, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, p. 22, ISBN 978-0-253-35655-0

- ^ Ulivi, Paolo (April 6, 2004). Lunar Exploration: Human Pioneers and Robotic Surveyors. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-85233-746-9. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Morrison, David (January–February 2007). "Carl Sagan's Life and Legacy as Scientist, Teacher, and Skeptic". Skeptical Inquirer. 31 (1): 29–38. ISSN 0194-6730. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ Reiffel, Leonard (May 4, 2000). "Sagan breached security by revealing US work on a lunar bomb project". Nature. 405 (13): Correspondence. doi:10.1038/35011148. PMID 10811192.

- ^ "Who's Out There? - Films - Drew Associates". Drew Associates. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "Happy (Belated) Birthday Carl!". University of California, Berkeley The Berkeley Science Review. November 11, 2013. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Davidson 1999, p. 138.

- ^ a b Davidson 1999, p. 204.

- ^ Sagan, Carl. Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (on Google Books, Archived 3 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine), Ballantine Books (1996) p. 25.

- ^ Davidson 1999, p. 213.

- ^ Sagan, Carl; Head, Tom (2006). Conversations with Carl Sagan (illustrated ed.). Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. xxi. ISBN 978-1-57806-736-7. Extract of page xxi Archived December 23, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Sagan, Carl (January 5, 1995). "An Interview with Carl Sagan". Charlie Rose (Interview). PBS. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ Pierrehumbert, Raymond T. (2010). Principles of Planetary Climate. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-139-49506-6. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2016. Extract of page 202 Archived December 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Much of Sagan's research in the field of planetary science is outlined by William Poundstone. Poundstone's biography of Sagan includes an 8-page list of Sagan's scientific articles published from 1957 to 1998. Detailed information about Sagan's scientific work comes from the primary research articles. Example: Sagan, C.; Thompson, W. R.; Khare, B. N. (1992). "Titan: A Laboratory for Prebiological Organic Chemistry". Accounts of Chemical Research. 25 (7): 286–292. doi:10.1021/ar00019a003. PMID 11537156. There is commentary on this research article about Titan at David J. Darling's The Encyclopedia of Science Archived March 10, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Chaisson, Eric; McMillan, Stephen (1997). Astronomy Today (illustrated ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-13-712382-7. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1985) [Originally published 1980]. Cosmos (1st Ballantine Books ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-33135-9. LCCN 80005286. OCLC 12814276.

- ^ Carl Sagan testifying to Congress, December 10, 1985, C-SPAN, https://www.c-span.org/video/?125856-1/greenhouse-effect Archived December 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sagan, Carl Edward". Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. May 2001. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ No Writer Attributed (August 21, 1963). "Sagan Synthesizes ATP In Laboratory". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ "Carl Sagan". Pasadena, CA: The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ Benford, Gregory (1997). "A Tribute to Carl Sagan: Popular & Pilloried". Skeptic. 13 (1). Archived from the original on April 16, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ Shermer, Michael (November 2, 2003). "Candle in the Dark". The Works of Michael Shermer. Michael Shermer. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2013. Article originally published in November 2003 issue of Scientific American.

- ^ Impey, Chris (January–February 2000). "Carl Sagan, Carl Sagan: Biographies Echo an Extraordinary Life". American Scientist (Book review). 88 (1). ISSN 0003-0996. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Carl Sagan". EMuseum. Minnesota State University, Mankato. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ "CosmoLearning Astronomy". CosmoLearning. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Vergano, Dan (March 16, 2014). "Who Was Carl Sagan?". National Geographic Daily News. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Browne, Ray Broadus (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. p. 704.

- ^ a b c "Cosmos". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ Popular Science, Oct. 2005, p. 90.

- ^ Golden, Frederic (October 20, 1980). "The Cosmic Explainer". Time. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c Sagan & Druyan 1997, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Shapiro, Fred R., ed. (2006). The Yale Book of Quotations. Foreword by Joseph Epstein. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 660. ISBN 978-0-300-10798-2. LCCN 2006012317. OCLC 66527213.

- ^ Frazier, Kendrick, ed. (July–August 2005). "Carl Sagan Takes Questions: More From His 'Wonder and Skepticism' CSICOP 1994 Keynote". Skeptical Inquirer. 29 (4). Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ 24fpsfan (December 22, 2012). "Carl Sagan (Cosmos) Parody by Johnny Carson (1980)". Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Safire, William (April 17, 1994). "Footprints on the Infobahn". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2013.