Albertina Sisulu

Albertina Sisulu | |

|---|---|

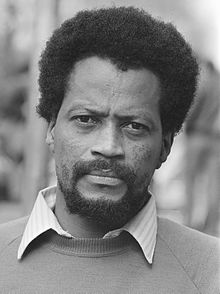

Sisulu in April 2007 | |

| Member of the National Assembly | |

| In office May 1994 – June 1999 | |

| Deputy President of the African National Congress Women's League | |

| In office April 1991 – December 1993 | |

| President | Gertrude Shope |

| Succeeded by | Thandi Modise |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nontsikelelo Thethiwe 21 October 1918 Camama, Transkei Union of South Africa |

| Died | 2 June 2011 (aged 92) Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Political party | African National Congress |

| Other political affiliations | United Democratic Front |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Known for | Anti-apartheid activism |

Albertina Sisulu OMSG (née Nontsikelelo Thethiwe; 21 October 1918 – 2 June 2011) was a South African anti-apartheid activist. A member of the African National Congress (ANC), she was the founding co-president of the United Democratic Front. In South Africa, where she was affectionately known as Ma Sisulu, she is often called a mother of the nation.

Born in rural Transkei, Sisulu moved to Johannesburg in 1940 and was a nurse by profession. She entered politics through her marriage to Walter Sisulu and became increasingly engaged in activism after his imprisonment in the Rivonia Trial. In the 1980s she emerged as a community leader in her hometown of Soweto, assuming a prominent role in the establishment of the UDF and the revival of the Federation of South African Women.

Between 1964 and 1989, she was subject to a near-continuous string of banning orders. In addition to intermittent detention without trial, she was subject to criminal charges on three occasions: she was acquitted of violating pass laws in 1958, convicted of violating the Suppression of Communism Act in 1984, and acquitted of violating the Internal Security Act in the 1985 Pietermaritzburg Treason Trial.

After the end of apartheid, Sisulu represented the ANC in the first democratic Parliament before she retired from politics in 1999. She was also the deputy president of the ANC Women's League from 1991 to 1993 and a member of the ANC National Executive Committee from 1991 to 1994.

Early life and education[edit]

Sisulu was born on 21 October 1918 in the Camama, a village in the Tsomo region of the Transkei.[1] She was the second of five siblings in a Xhosa (Mfengu) family.[2] Her father, Bonilizwe Thetiwe, was a migrant worker who spent long stints working in the gold mines of the Transvaal, and her mother, Monica Thetiwe (née Mnyila), was disabled by the bout of Spanish flu that she had suffered while pregnant with Sisulu.[1][3] Sisulu and her siblings spent most of their childhood with their maternal grandparents in the village of Xolobe, where Sisulu began school at a Presbyterian mission. Though her family called her "Ntsiki" throughout her life, she assumed the name Albertina at school, choosing it from a list of European Christian names provided by her missionary schoolteachers.[1]

In 1929, while Sisulu's mother was pregnant with her fifth and final child, Sisulu's father died of occupational lung disease in Camama.[1] Her mother remained in ill health until her death in 1941, so Sisulu – both the eldest sister and the eldest female cousin – became a primary caregiver to her younger siblings and cousins, with frequent interruptions to her education as a result.[1][4] Nonetheless, in 1936, she received a scholarship for secondary schooling at Mariazell College, a Catholic boarding school in Matatiele.[1] She covered her living expenses by ploughing fields and working in the laundry room during school holidays.[3] Newly converted to Catholicism, she intended to become a nun or school principal, but her headmaster, Father Bernard Huss, convinced her to pursue training as a nurse after she finished school in 1939.[3]

Anti-apartheid activism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

In January 1940, Sisulu moved to Johannesburg, where she began her long nursing career as a trainee in the non-European section of the Johannesburg General Hospital.[3] She qualified as a nurse in 1944 and later qualified as a midwife too.[5] Her interest in politics grew through her association with Walter Sisulu, a real estate agent and activist in the African National Congress (ANC), who courted and then married her. She began attending ANC meetings not as a member but as his companion.[6] In her own description, "I had no political ideas. I was devout until I met Walter."[7] Ellen Kuzwayo, another of the few women present at such meetings, later remembered her as "a kind hostess who served the committee members of the congress with tea after long and intense meetings".[6] In this capacity, as Walter's fiancée, she was the only woman present at the inaugural meeting of the ANC Youth League in 1944.[6][8]

According to Pippa Green, she joined the ANC Women's League in 1946.[9] In addition, the Sisulus' home in Orlando West, a suburb of Soweto outside Johannesburg, was long-established as a meeting place for ANC leaders.[3][10] However, her husband's political activities made Sisulu the family's main breadwinner, and she did not actively participate in ANC activities until the 1950s, by which time the National Party had introduced its programme of institutionalised apartheid.[1] She abstained from the 1952 Defiance Campaign, during which Walter was arrested and convicted of communism; in her paraphrase of the ANC's policies, "if one of the members of the family was already defying, we couldn't all go, because there were children to be looked after".[9]

1948–1963: Pre-Rivonia Trial[edit]

Opposition to apartheid accelerated in 1954 and 1955, and Sisulu was involved in several related campaigns. She was elected to the inaugural national executive committee of the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) when it was founded in 1954.[11] In 1955, she participated in the Freedom Charter leafleting campaign ahead of the Congress of the People, and at the same time participated in a boycott of public schools in protest of the Bantu Education Act; the Sisulus' home housed one of the so-called alternative schools set up as part of the protest.[1] She was present at the August 1956 Women's March in Pretoria,[12][13] and in October 1958 she was arrested for the first time and charged for participating in another women's march against pass laws.[1] On the latter occasion, she was detained for three weeks on charges of violating the pass laws, but she was ultimately acquitted, with her husband's close friend Nelson Mandela as her lawyer.[9][14] In the early 1960s, she was involved in an ANC scheme to recruit nurses as volunteers to relocate to newly independent Tanganyika, a personal favour from Oliver Tambo to Julius Nyerere.[15][16]

Meanwhile, Sisulu's husband was a defendant in the 1956–1961 Treason Trial, and their home became a target for Security Branch attention and raids.[1][17] After the 1960 Sharpeville uprising, the apartheid government banned the ANC and several associated organisations; shortly afterwards, the ANC announced the inauguration of armed struggle. Her husband, a founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe, went into hiding underground in 1963. On 19 June of that year, Sisulu became the first woman to be detained under the so-called 90-Day Detention Law: the recently enacted General Laws Amendment Act, 1963 allowed police to detain activists incommunicado indefinitely and without charging them.[2] She was held in solitary confinement and interrogated at length about Sisulu's whereabouts.[3] She was released after her husband and his comrades were apprehended at Rivonia in July 1963.[3] The ensuing Rivonia Trial concluded in June 1964 with Walter being sentenced to life imprisonment. During the trial, Sisulu redoubled her engagement with the ANC Women's League.[1]

1964–1989: Post-Rivonia Trial[edit]

I knew why the government hated me. It was because I was against apartheid. I was aware that I was the government's enemy. Nothing could have pleased me more.

– Sisulu on her persecution by the apartheid government[9]

In August 1964, in the aftermath of the Rivonia convictions, Sisulu was served with the first in a series of banning orders.[2] She was banned continuously for the next 17 years, prohibited from political activity and for several years confined to effective house arrest.[1] The Minister of Law and Order allowed her fourth ban to lapse in August 1981, and she celebrated by making an address – her first political speech since the early 1960s – at a local church's commemoration of the Women's March.[18] The respite lasted less than a year before she was arrested and served with another banning order, her fifth, in June 1982;[1][19] that order was part of a more general crackdown effected in Soweto during commemorations of the 1976 Soweto uprising.[20]

Nonetheless, throughout this period, Sisulu remained a prominent figure in the resistance movement, notable for her focus on civic organising on a national rather than local scale. She was particularly influential in the preparations for the establishment of the United Democratic Front (UDF), a popular front against apartheid that was launched in 1983, and in a protracted campaign to revive FEDSAW.[21] From the 1970s, she was active in the political mentorship of younger women activists such as Jessie Duarte and Susan Shabangu; Duarte later said that Sisulu's protégés considered themselves "MaSisulu's girls", and she was instrumental in the foundation of a Soweto-based underground ANC cell for women, named Thusang Basadi ("wake up women").[1]

Communism trial and UDF launch[edit]

Sisulu's June 1982 banning order was allowed to lapse after only a year,[22] and in July 1983 she attended meetings of the national steering committee that was preparing for the national launch of the UDF.[1] However, on 5 August, she was arrested again at her workplace and charged with a violation of the Suppression of Communism Act.[23] She and her co-accused, activist Thami Mali, were accused of having conspired to further the aims of the banned ANC in connection with their role in planning the funeral of Rose Mbele, an ANC Women's League Stalwart. The funeral had taken place months earlier – on 16 January 1983 in a church in Soweto – and the charges were widely viewed as a justification to detain Sisulu ahead of the UDF's launch.[1]

Later in August, while Sisulu was awaiting trial in solitary confinement in Diepkloof, the UDF was launched. She was elected in absentia as the regional president of the UDF's Transvaal branch, and then, at the front's national launch in Mitchell's Plain on 20 August, as one of the three national co-presidents of the UDF, the others being Oscar Mpetha and Archie Gumede.[1] Her trial began in Krugersdorp shortly afterwards, with George Bizos as her defence counsel. On 24 February 1984, in a ruling condemned by the United Nations Special Committee against Apartheid, she was convicted and sentenced to four years' imprisonment, with two years of the sentence suspended for five years.[1] However, she was also released on bail pending an appeal, allowing her to resume her political activities;[1] she said that, after several consecutive months in solitary confinement, "I came out speaking to the walls".[9] The appeal against her sentence was ultimately upheld in 1987.[24]

Abu Baker Asvat and Mandela United[edit]

In 1983, Sisulu retired from public nursing, having reached retirement age and received her pension.[5] The following year, in the aftermath of her criminal trial, she began work as receptionist and nursing assistant in Rockville, Soweto in the private surgery of Abu Baker Asvat, a doctor who was renowned for his humanitarianism.[1] Although Asvat was a leading member of the Azanian People's Organisation, a rival of the UDF, the pair worked closely together;[25] she later said that they were like mother and son,[26] and he did not object to Sisulu's political activities, which continued in earnest.[1]

This period was also marked by increasing tension between Sisulu and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Nelson Mandela's wife, whose Mandela United Football Club engaged in gangsterism and intimidation in Soweto from around 1986 onward. Because of the friendship between their husbands, Sisulu and Madikizela-Mandela had been close during their youth; arrested together in 1958, Sisulu had nursed Mandela through the near-miscarriage of her first child in a jail cell.[1][27] However, in the 1980s, their relationship grew tense as Sisulu attempted to curb Mandela United's excesses.[1] Sisulu later said that, "As a woman, I tried to pull her out of that... Winnie and I were never enemies, I tried to help her."[27] According to historian Jonny Steinberg, other members of the community delegated Sisulu to report their concerns about Madikizela-Mandela's behaviour to the exiled ANC leadership in Lusaka, Zambia; her home was burned down soon afterwards in what she believed was a retaliatory arson attack by Mandela United.[28] In later years, because of their husbands' stature, the press often contrasted Madikizela-Mandela and Sisulu as opposing models of female activism, comparing Sisulu's cool-headed maturity with Madikizela-Mandela's "rage and charm".[27][29][30]

Meanwhile, Asvat was an unpopular figure both with the state and with conservative residents of Soweto; in 1987, Sisulu was with him when he narrowly escaped a knife attack, and in December 1988, they worked without water or electricity after the supply to their surgery was cut off.[25] On the afternoon of 27 January 1989, Asvat was fatally shot at his surgery while Sisulu was in the dispensary at the rear of the clinic; he died shortly afterwards in Sisulu's presence. She had admitted the gunmen to an appointment with Asvat earlier that day.[31] Madikizela-Mandela and her Football Club long faced rumours of having arranged Asvat's assassination,[32] and Sisulu was publicly drawn into those accusations in 1997 ().

Pietermaritzburg Treason Trial[edit]

In 1984, while Sisulu was working at Asvat's surgery and awaiting the appeal of her criminal conviction, the UDF vastly expanded its national presence through an intensive campaign of opposition to President P. W. Botha's constitutional reforms, including the Black Authorities Act, 1982 and the 1983 Constitution. The first elections to the Tricameral Parliament in August 1984 were marred by a successful UDF boycott, followed by widespread township uprisings.[33] In a subsequent crackdown by Botha's government, Sisulu was arrested on 19 February 1985.[34] She and 15 others were charged under the Internal Security Act with treason and incitement to overthrow the government. As the only woman accused, she was held in detention alone.[1]

On 3 May 1985, Sisulu and her co-accused were released on bail with stringent conditions.[35] The ensuing Pietermaritzburg Treason Trial opened on 21 October in the Natal Supreme Court with the defendants' not-guilty plea,[36] but the charges against Sisulu and 11 others were dropped on 9 December.[37] Sisulu told press it was "a crushing victory for us".[38] Popular uprisings continued, and Sisulu was banned again in 1986[9] and in early 1988.[39][24]

1989–1994: Negotiations[edit]

In 1989, as the negotiations to end apartheid quickened, Sisulu embraced her public-facing role in the anti-apartheid movement. In June that year, she was granted her first South African passport – an abrupt reversal, given that her latest banning order had been renewed only days earlier.[40] Later that month, she led a UDF delegation on an international tour, which included a meeting with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[33] While in London, she met with Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock and addressed a major rally of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement.[1][41] On 30 June 1989, she met with American President George H. W. Bush in the White House.[42][43] The delegation also travelled to Sweden; to France, on the invitation of Danielle Mitterrand; and to the ANC's headquarters in exile in Lusaka, where Sisulu provided exiled leaders with a report on conditions inside South Africa.[1]

The last of the restrictions against Sisulu were lifted by the South African government on 14 October 1989.[44] Meanwhile, President F. W. de Klerk's government unbanned the ANC in 1990, permitting the party to resume overt organising inside South Africa. Sisulu became involved in the campaign to re-establish the ANC Women's League, though she declined a nomination to stand for the league's presidency. Instead, at the league's first national conference in Kimberley in April 1991, she threw her support behind Gertrude Shope, who defeated Madikizela-Mandela to become the league's president.[1] At the same conference, Sisulu was elected to deputise Shope as the league's deputy president.[45][46] Over the next two years, she worked at the league's downtown headquarters in Shell House.[47] However, she held the deputy presidency for only one term, ceding the office to Thandi Modise at the league's next national conference in December 1993.[48]

The mainstream ANC held its own reunion in July 1991 at the 48th National Conference in Durban, where Sisulu was elected to serve as a member of the party's National Executive Committee.[49] She only served one three-year term in the committee; at the 49th National Conference in December 1994, both she and her husband declined to stand for re-election to the party's leadership.[50]

Post-apartheid political career[edit]

National Assembly[edit]

Sisulu later said that, as a member of the ANC National Executive, she had been highly doubtful of Mandela's proposal to reconcile with National Party supporters in the interests of national unity. As she told a reporter, "The first meeting of the [ANC] national executives, when Mandela introduced this to us, we all stood up and said, 'He's now mad.' We thought he was mad, to say we must reconcile. Shooo!".[27] Nonetheless, ahead of the first post-apartheid democratic elections, she accepted nomination to stand as an ANC candidate for election to the new multi-racial Parliament of South Africa, and she was comfortably elected to a seat in the lower house, the National Assembly.

When the Houses of Parliament opened on 10 May 1994, it was Sisulu who formally nominated Mandela to serve as the first post-apartheid President of South Africa.[51] Her biographer said it was "one of the proudest moments of her life" to be selected to offer the nomination on the ANC's behalf.[52] She served one term in Parliament, retiring at the June 1999 general election.[1]

Truth and Reconciliation Commission[edit]

During this period, her most prominent engagement was that with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1997. She was expected to provide important testimony in the TRC's investigation into the activities of the Mandela United Football Club, in particular through her account of the day of Asvat's murder and of the relationship between Asvat and Madikizela-Mandela.[53] Moreover, earlier that year, a videotaped interview with Sisulu had been included in Katiza's Journey, a BBC documentary in which journalist Fred Bridgland claimed to uncover evidence that Madikizela-Mandela had conspired to kidnap Stompie Seipei as well as to murder Asvat. In that interview, Sisulu had confirmed the authenticity of a patient record card from Asvat's surgery which undermined Madikizela-Mandela's alibi on the day of Seipei's death; she said that she recognised her own handwriting on the card. She later said that she had made this identification in error.[1]

Sisulu's appearance before the TRC on 1 December received international attention.[54][55] However, after giving an emotional account of Asvat's shooting, she provided what were described as "evasive" responses to questions about Madikizela-Mandela's involvement in Asvat and Seipei's deaths; she denied having signed the crucial patient record card, denied any knowledge of a row between Madikizela-Mandela and Asvat, and said, "I wouldn't think that Mrs. Mandela could kill Asvat because I thought they were friendly".[26][56] She said that she did not recall having seen Madikizela-Mandela or her colleagues at the surgery during the period of Seipei's kidnapping.[57]

During intensive cross-examination, TRC commissioner Dumisa Ntsebeza told Sisulu that she appeared to be "trying your very best to say as little as possible, anything that can implicate Mrs. Mandela" and asked whether this was because of "struggle morality" – because "she is your comrade and the Mandela and Sisulus go back a very long way".[58][59] Sisulu responded with indignant weeping, recounting her years of involvement in activism and saying, "Even if I am shielding her, I am not here to tell lies."[26][58] Commissioner Alex Boraine also expressed dissatisfaction with apparent inconsistencies in Sisulu's testimony.[60]

The day after her testimony, Sisulu and her husband met with Desmond Tutu, the chairman of the TRC, to discuss her unhappiness at having been accused of dishonesty.[61] On 4 December, the TRC heard further evidence which confirmed Sisulu's account that it was not her signature on the disputed record card. Sisulu briefly re-appeared on the witness stand, at her own request, and Ntsebeza told her that she had been "vindicated" and restored as "an icon of moral rectitude".[61]

Personal and family life[edit]

Sisulu met her husband, Walter, in 1941, and their families agreed on lobola the following year; they married on 15 July 1944 in a civil ceremony in Cofimvaba.[1] Walter's best man was Nelson Mandela, and one of Albertina's bridesmaids was Mandela's first wife, Evelyn Mase; Mase was Walter's maternal cousin and had met Mandela at the Sisulus' home.[1] During reception speeches by A. B. Xuma and Anton Lembede,[1] Lembede warned Albertina that, "You are marrying a man who is already married to the nation".[62] Sisulu later recalled, "I told her it was useless buying new furniture. I was going to be in jail."[63] They did not have a honeymoon until November 1990, when they travelled together to the Crimean resort of Yalta on ANC business.[1]

The Sisulus' four-room home in Orlando West accommodated a rotation of young relatives, including Sisulu's younger siblings and five children of their own born between August 1945 and October 1957, and Sisulu raised them alone while Walter was on Robben Island from 1964 to 1989.[1] In the early years of Walter's imprisonment, she spent her spare time sewing, knitting, and reselling eggs to raise money to cover her children's school tuition, determined that they should attend boarding school in neighbouring Swaziland rather than join the South African Bantu Education system.[1]

From their young adulthood onwards, the children were also periodically detained and banned by the apartheid police between stints in exile with the ANC.[1] While Sisulu and her son were both banned in the 1980s, they received special police authorisation to be allowed to speak to each other, in exception to provisions that criminalised gatherings between banned individuals; since they lived in the same Soweto home, Sisulu dismissed the rule as "nonsense",[18] joking, ''What was I supposed to do? Not ask him what he wanted for breakfast?''[40] This notwithstanding, she later said that above all else it was her children's detentions that made her feel "that the Boers were breaking me at the knees."[10]

Sisulu was rarely able to travel to Cape Town to visit her husband on Robben Island,[64] but Ruth First said of their marriage in 1982 that, "His capacity to lead and her political strength are... the product of a good marriage, a good political marriage, but a good marriage, one that is based on genuine equality and on shared commitment."[63] Sisulu herself famously said, "We loved each other very much. We were like two chickens. One always walking behind the other."[65] On another occasion, she reflected:

[Y]ou know, of all the people around here, he’s the only one – perhaps there are one or two – who are progressive. I was emancipated the day I got married. There was no question of 'Go and make tea' or 'Polish my shoes.' He used to wash his children and put them to bed. You know, I never felt I was a woman in the house.[66]

On 10 October 1989, Sisulu was visiting Mandela at Victor Verster Prison when she learned of her husband's impending release through an SABC broadcast.[9][67][68] His health had deteriorated in prison and when Sisulu was nominated to stand for Parliament in 1994, Mandela suggested that she might decline the nomination in order to care for Walter. Her children were so incensed by the suggestion that Mandela called to apologise to them and rescind his advice.[69] The couple lived in Orlando until after her retirement, when they moved to the Johannesburg suburb of Linden.[70] Walter died at home on 5 May 2003 in Sisulu's presence.[71] At his funeral, one of their granddaughters read a poem written by Sisulu, entitled, "Walter, what do I do without you?".[72]

The Sisulus' children also went on to hold positions of influence in post-apartheid South Africa. Their biological children were Max (born August 1945), Mlungisi (born November 1948), Zwelakhe (born December 1950, during an ANC national conference), Lindiwe (born May 1954), and Nonkululeko (born October 1957).[1] Max's wife, Elinor Sisulu, published a biography of her parents-in-law in 2002 entitled Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime.[73] The Sisulus also adopted Walter's sister's two children, Gerald and Beryl Lockman (born in December 1944 and March 1949 respectively), and raised the son of Walter's cousin, Jongumzi Sisulu (born 1958).[1] At the time of her death, Sisulu had 26 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.[4] Despite her former Catholicism, she raised her children in the Anglican Church at the wishes of Walter's mother;[1] by 1992, however, when asked whether she and Walter were still practising Christians, she replied, "There’s no time, my dear".[74]

Death and funeral[edit]

Sisulu died unexpectedly at her home in Linden on 2 June 2011, aged 92.[65][75] She was watching television with two of her grandchildren when she had a coughing fit and lost consciousness; paramedics were not able to revive her.[76][77] She was buried on 11 June next to her husband's grave in Croesus Cemetery in Newclare, Johannesburg.[78]

Obituaries and tributes to Sisulu celebrated her as the mother of the nation.[3][76][79][80] In his own statement, President Jacob Zuma said that, "Mama Sisulu has, over the decades, been a pillar of strength not only for the Sisulu family but also the entire liberation movement, as she reared, counselled, nursed and educated most of the leaders and founders of the democratic South Africa".[81] He also announced that Sisulu would receive a state funeral, and that the national flag would be flown at half-mast from 4 June until the day of her burial on 11 June.[82]

Memorial services were held throughout the week,[83] followed on 11 June by the official funeral at Soweto's Orlando Stadium.[84][85] President Zuma delivered a eulogy, after leading the crowd in verses of struggle song Thina Sizwe,[86] and Graça Machel read a message from former President Mandela which heralded Sisulu as his "beloved sister" and as the "mother of all our people".[78]

Honours[edit]

The city of Reggio Emilia, Italy granted Sisulu honorary citizenship of the city in 1987,[87] and the following year, the Sisulu family was jointly awarded the Carter Center's Carter-Menil Human Rights Award, though neither Sisulu nor her husband – banned and imprisoned respectively – could travel to Georgia to accept the prize.[40] In 1993 she was elected as president of the World Peace Council.

After the end of apartheid, she was awarded honorary doctorates by the University of the Witwatersrand in 1999, the University of Cape Town in 2005, and the University of Johannesburg in 2007.[88][89] On her 85th birthday in 2003, she was present at the unveiling of the Albertina Sisulu Centre, a community centre built by the City of Johannesburg in Orlando West to serve children and adults with special needs.[90] In 2004 she was ranked 57th in SABC3's controversial Great South Africans poll,[91] and in 2007 she received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the annual Community Builder of the Year Awards, hosted by SABC, Old Mutual, and the Sowetan.[92] She also received the Order for Meritorious Service.

In 2007, the Gauteng Provincial Government announced that it would rename the R21–R24 highway system between Pretoria and the O. R. Tambo International Airport as the Albertina Sisulu Freeway.[93][94] In line with this decision, the Johannesburg Metropolitan Council resolved in 2008 to rename 18 municipal roads after Sisulu, thereby preserving the name change in the non-freeway sections of the R24 that pass through downtown Johannesburg.[95] The renaming of the R24's freeway and non-freeway sections was completed in 2013.[96][97][98] Outside of South Africa, the Albertina Sisulu Bridge, which crosses the Scheldt, was given its name by the City of Ghent, Belgium in 2014.[99]

In 2018, the centenary of Sisulu's birth, the South African government held a number of further initiatives to honour Sisulu. As part of this programme, the South African Post Office launched a commemorative stamp,[100][101] and a rare species of orchid, brachycorythis conica subsp. transvaalensis, was renamed the Albertina Sisulu Orchid during a ceremony at the Walter Sisulu Botanical Garden.[102] The national government hosted the Albertina Sisulu Women's Dialogue in Johannesburg,[103] and UNICEF co-hosted another Albertina Sisulu Dialogue in Durban during that year's National Women's Month,[104] In 2021, the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Innovation launched the Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu Science Centre, a green technology science centre in Cofimvaba, Eastern Cape.[105]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Sisulu, Elinor (2003). Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime. New Africa Books. ISBN 0-86486-639-9.

- ^ a b c Isaacson, Maureen (6 June 2011). "Sisulu: A life well lived". Independent. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Herbstein, Denis (12 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu: Nurse and freedom fighter revered by South Africans as the mother of the nation". The Independent. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b McGregor, Liz (6 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b Leist, Reiner (September 1991). "Albertina Sisulu". Blue Portraits. Archived from the original on 5 October 1999. Retrieved 11 June 2024 – via African National Congress.

- ^ a b c d Sisulu, Elinor (10 June 2011). "Tribute: Life, love and times of the Sisulus". The New Age. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu, Freedom Fighter". Sechaba. October 1988. Archived from the original on 15 June 2002. Retrieved 11 June 2024 – via African National Congress.

- ^ Bell, Jo (2021). On This Day She: Putting Women Back Into History, One Day at a Time. Tania Hershman, Ailsa Holland. London: Metro. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-78946-271-5. OCLC 1250378425.

- ^ a b c d e f g Green, Pippa (9 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu's Story of Persecution and Suffering, Love and Triumph". allAfrica. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b Bearak, Barry (5 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu, Who Helped Lead Apartheid Fight, Dies at 92". The New York Times.

- ^ Green, Pippa (9 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu's Story of Persecution and Suffering, Love and Triumph". allAfrica. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "60 Iconic Women — The people behind the 1956 Women's March to Pretoria". The Mail & Guardian. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu never aimed for politics". News24. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Struggle heroine Albertina Sisulu dies". The Mail & Guardian. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Untold story of South African nurses who helped Tanzania after British nurses refused to work under black leadership". The Citizen. 18 March 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "The story of Albertina Sisulu's nurses". The Mail & Guardian. 8 November 2003. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu's story". News24. 8 August 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b Lelyveld, Joseph (24 August 1981). "A Soweto Woman Regains Her Political Voice". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Fifth banning order for Albertina Sisulu". South African History Online. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Lelyveld, Joseph (17 June 1982). "South African Police and Youths Clash Outside a Church in Soweto". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu, veteran of anti-apartheid movement, dies at 92". Washington Post. 3 June 2011. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Lelyveld, Joseph (2 July 1983). "Pretoria Ends Banning Orders for 50". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "S. Africa Jails Woman Weeks After Lifting 17-Year House Arrest". Washington Post. 9 August 1983. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Pen portraits of a dozen of those banned yesterday". The Mail & Guardian. 25 February 1988. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Profile: Abu Asvat". The Mail & Guardian. 2 February 1989. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b c "Star witness refuses to damn Winnie". The Independent. 2 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d "South Africa's Mother Figures". Washington Post. 19 April 1996. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Malan, Rian (9 June 2023). "The moral icon and the murderess". Vrye Weekblad (in Afrikaans). Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Love in a time of burning: Remembering Winnie Mandela". LitNet. 3 April 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Gilbey, Emma (14 April 1992). "Winnie Mandela's Rise and Fall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "I Heard Shots That Killed Asvat, Says Mrs Sisulu". SAPA. 1 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Winnie Mandela and the people's doctor". Africa Is a Country. 4 June 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b Seekings, Jeremy (2000). The UDF: A History of the United Democratic Front in South Africa, 1983–1991. New Africa Books. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-86486-403-1.

- ^ "6 Critics of Apartheid Seized in South Africa". Los Angeles Times. 19 February 1985. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "16 released on bail in South Africa treason trial". UPI. 3 May 1985. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "South Africans Open A Major Treason Trial". The New York Times. 22 October 1985. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "South Africa Clears 12 of Treason: Charges Against Most Prominent Foes of Apartheid Dropped". Los Angeles Times. 9 December 1985. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Rule, Sheila (10 December 1985). "South Africa Ends A Case Against 12". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Sisulu and the Unity of Struggle". Washington Post. 11 May 1988. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Perlez, Jane (27 June 1989). "Apartheid Foe Gets Passport And Is Expected to Meet Bush". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu addresses a major anti-apartheid rally in London". South African History Online. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "South African Dissident Calls For U.S. Pressure". Washington Post. 30 June 1989. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Bush Listens to a True Voice of South Africa". Washington Post. 25 July 1989. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Green, Pippa (9 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu's Story of Persecution and Suffering, Love and Triumph". allAfrica. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Winnie Mandela's Defeat In ANC Vote Is Hailed". Christian Science Monitor. 30 April 1991. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Wren, Christopher S. (29 April 1991). "Winnie Mandela Loses Women's League Vote". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Shaka Sisulu: The Gogo stories". The Mail & Guardian. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ 'For Freedom and Equality': Celebrating Women in South African History (PDF). South African History Online. 2011. p. 26.

- ^ Ramaphosa, Cyril (1994). "Report of the Secretary-General to the 49th National Conference". African National Congress. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "1994 Conference". Nelson Mandela: The Presidential Years. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ "It's a 'New Era,' Says Officially Elected Mandela". Los Angeles Times. 10 May 1994. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Sisulu, Elinor (15 December 2013). "Nelson Mandela remembered by Elinor Sisulu". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "More corpses in Winnie's cupboard". The Mail & Guardian. 20 November 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Key Witness Backs Madikizela-Mandela". Washington Post. 2 December 1997. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Daley, Suzanne (2 December 1997). "Panel Hears Evidence Winnie Mandela Sought Doctor's Death". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Testimony focuses on Madikizela-Mandela's alleged link to doctor's murder". CNN. 1 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Asvat murderer in tears". The Mail & Guardian. 1 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Ntsebeza Questions Sisulu's Testimony on Winnie". SAPA. 1 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Winnie hearing adjourned after intimidation claims". BBC News. 1 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Lies and More Lies at the Truth Commission, Complains Boraine". SAPA. 1 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Sisulu Vindicated at TRC Hearing: Commissioner". SAPA. 4 December 1997. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Obituary: Walter Sisulu". The Mail & Guardian. 6 May 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b Green, Pippa (1990). "Free at last". The Independent. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "A South Africa Choice: See Husband, or Son". The New York Times. 18 May 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b Smith, David (3 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu, one of 'mothers' of liberated South Africa, dies aged 92". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu: The 'Mother' of South Africa's Freedom Fighters Fights On". Los Angeles Times. 19 July 1992. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Black Leaders To Be Released In South Africa". The New York Times. 11 October 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Sparks, Allister (15 October 1989). "S. Africa Frees Sisulu, 5 Other Black Activists". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Sisulu, Elinor (15 December 2013). "Nelson Mandela remembered by Elinor Sisulu". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "MaSisulu: mother in jail, mother in the suburbs". City of Johannesburg. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Lelyveld, Nita (6 May 2003). "Walter Sisulu, 90; Political Leader Helped Shape Anti-Apartheid Fight". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "'What do I do without you?'". The Mail & Guardian. 18 May 2003. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Suttner, Raymond (7 February 2003). "A revolutionary love". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu: The 'Mother' of South Africa's Freedom Fighters Fights On". Los Angeles Times. 19 July 1992. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu: South Africa loses a moral compass". BBC News. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Albertina Sisulu 'was truly the mother of the nation'". The Mail & Guardian. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "A love story ends". The Star. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Madiba mourns his 'beloved sister' Albertina Sisulu". The Mail & Guardian. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu 1918–2011: Tributes". Sunday Times. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "In quotes: Albertina Sisulu remembered". BBC News. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "MaSisulu – mother to a nation". Business Day. 3 June 2011. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "SA mourns anti-apartheid icon 'Ma' Sisulu". The Namibian. NAMPA. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

- ^ "Sisulu's funeral to be held at Orlando Stadium". The Mail & Guardian. 5 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu funeral held in South Africa". BBC News. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu's final journey". The Mail & Guardian. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Zuma celebrates Sisulu, the 'outstanding patriot'". The Mail & Guardian. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Reggio Emilia and SA's liberation struggle". Africa Reggio Emilia Alliance. 3 September 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Liberation leaders honoured for their contributions to democracy". University of Johannesburg. 19 April 2007. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Four honorary degrees for grad". University of Cape Town. 5 December 2005. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu Centre Opened in Soweto". BuaNews. 22 October 2003. Retrieved 10 June 2024 – via allAfrica.

- ^ "The 10 Greatest South Africans of all time". Bizcommunity. 27 September 2004. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Steve Biko, Albertina Sisulu, Beyers Naude honoured as great South Africans". Sowetan. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Gauteng to rename R21/R24 road to Albertina Sisulu Drive, 30 Aug". South African Government. 28 August 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "R21 renamed Albertina Sisulu". News24. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Ma Sisulu's name to be on 18 Joburg streets". IOL. 10 September 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Maseng, Kabelo (21 October 2013). "Market Street makes way for Albertina Sisulu". Rosebank Killarney Gazette. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Zuma renames R24 after struggle hero". South African Government News Agency. 20 October 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu Road heralds a new era". IOL. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Gent eert anti-apartheidsleiders met straatnamen bij de Krook". HLN (in Dutch). 24 October 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "South Africa honours Albertina Sisulu". Vuk'uzenzele. May 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Stamps for Ma Albertina Sisulu". News24. 26 February 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Orchid to be named after Albertina Sisulu". Jacaranda FM. 6 July 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Women honour Albertina Sisulu". Sowetan. 11 November 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "UNICEF salutes the legacy of Albertina Sisulu". UNICEF South Africa. 25 August 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Minister launches science centre". News24. 14 October 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

External links[edit]

- Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu at South African History Project

- Albertina Sisulu Timeline: 1918–2011 at South African History Project

- Video of Mandela's presidential nomination at Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on 4 December 1997

- A Life of Fire and Hope: Albertina Sisulu at Apartheid Museum

- 1918 births

- 2011 deaths

- 20th-century South African politicians

- 20th-century South African women politicians

- African National Congress politicians

- Members of the National Assembly of South Africa

- People from Intsika Yethu Local Municipality

- Roman Catholic anti-apartheid activists

- South African anti-apartheid activists

- South African midwives

- South African nurses

- South African Roman Catholics

- Women members of the National Assembly of South Africa

- World Peace Council

- Xhosa people