Shabbat candles

Shabbat candles (Hebrew: נרות שבת) are candles lit on Friday evening before sunset to usher in the Jewish Sabbath.[1] Lighting Shabbat candles is a rabbinically mandated law.[2] Candle-lighting is traditionally done by the woman of the household,[3] but every Jew is obligated to either light or ensure that candles are lit on their behalf.[4]

In Yiddish, lighting the candles is known as licht bentschen ("light-blessing") or licht tsinden ("light-kindling").

History[edit]

According to Tobiah ben Eliezer, the custom is one "which Israel adopted from the time of Moses",[5] while Genesis Rabbah relates that "For all the days that Sarah lived, the Sabbath lamp stayed lit until the next Sabbath eve, and for Rebecca it did the same . . ."[6] According to Leopold Landsberg, the Jews adopted this custom from the Persians.[7] Jacob Zallel Lauterbach disagrees, arguing that it was instituted by the Pharisees to protest against superstition, or perhaps against (some predecessor of) the Karaitic refusal to have any light on Sabbath Eve, even were it lit before the Sabbath.[a][8] According to standard halakhic literature, the purpose of lighting of Shabbat candles is to dignify the Sabbath; before the advent of electric lighting, when the alternative was to eat in the dark, it was necessary to light lamps to create an appropriate environment.[9] One early-modern Yiddish prayer asks for the candles to "burn bright and clear to drive away the evil spirits, demons, and all that come from Lilith".[10]

The practice of lighting an oil lamp before Shabbat is first recorded in the second chapter of m. Shabbat, which already presupposes it as an old and undisputed practice.[8] Persius (d. 62 CE) describes it in Satire V:

At cum Herodis venere dies unctaque fenestra dispositae pinguem nebulam vomuere lucaernae portantes violas . . . labra moves tacitus recutitaque sabbata palles. But when the day of Herod[b] comes round, when the lamps wreathed with violets and ranged round the greasy window-sills have spat forth their thick clouds of smoke . . . you silently twitch your lips, turning pale at the sabbath of the circumcised. (trans. Menachem Stern)

As do Seneca and Josephus.[8][11]

Blessing[edit]

The blessing is never described by Talmudic sources, but was introduced by Geonim to emphasize rejection of the early Karaitic belief that lights could not be lit before the Sabbath.[8] It is attested in a fragment in the St. Petersburg national library (Antonin B, 122, 2); it also appears in a plethora of Gaonic material, including the Seder of Amram Gaon, the responsa of Natronai Gaon, the responsa of Sherira Gaon, and others. Every source quotes it with identical language, exactly correspondent to the modern liturgy.

Ritual[edit]

Who lights[edit]

The lighting is preferably done by a woman. Amoraic sources explain that "the First Man was the world's lamp, but Eve extinguished him. Therefore they gave the commandment of the lamp to the woman".[12] Rashi adds an additional rationale, "and moreover, she is responsible for household needs."[13] Maimonides, who rejects Talmudic rationales based on superstition,[14] writes only: "And women are more obligated in this matter than men, because they are found at home[c] and involved in housework."[15]

Yechiel Michel Epstein writes (cleaned up):

Sabbath lamps are just like Chanukah lamps, in that the obligation falls on the household. Therefore, even if a male member of the household has a separate room of his own, he need not light separately, because the woman's lighting accounts for every room of the house. If a married traveler has his own room, he needs to light separately, because his wife's blessing cannot account for another place entirely, but if he lacks his own room, he does not need to. A single traveler must light even if his parents are lighting on his behalf elsewhere, and if he lacks his own room, he must arrange matters with the proprietor.[16]

Ideally, the woman lights her candles in the place she will be eating dinner. If another woman wants to light there, she may also light in a different room. Similarly, a traveler may light within his room even if he is eating elsewhere.

Number of candles[edit]

Today, most Jews light at least two candles. Authorities up to and including Joseph Karo, who wrote that "there are those who employ two wicks, one corresponding to "Remember" and one corresponding to "Keep" (perhaps two wicks in one lamp, reflecting the Talmudic teaching "'Remember' and 'Keep' in a single statement"),[17] advised a maximum of two lamps, with other lamps necessary for other purposes kept carefully at a distance to preserve the tableau.[18] However, Moses Isserles added "and it's possible to add and light three or four lamps, and such is our custom",[19] and Yisrael Meir Kagan added, "and there are those who light seven candles corresponding to the seven days of the week (Lurianics),[20] or ten corresponding to the Ten Commandments".[21] Starting with Yaakov Levi Moelin, rabbinic authorities have required women who forgot to light one week to add an additional lamp to her regular number for the rest of her life.[22]

A recent custom reinterprets the two candles as husband and wife[d] and adds a new candle for every child born; apparently the first to hear of it was Israel Hayyim Friedman, though his essay was not published until 1965,[23] followed by Jacob Zallel Lauterbach, who mentions it in an undated essay published posthumously in 1951.[8] Menachem Mendel Schneerson mentioned it in a 1975 letter.[24] Mordechai Leifer supposedly said, "The women light two candles before children but after their first child they light five, corresponding to the Five Books Of Moses . . . and so it is forever, irrespective of how many children" but this teaching was not published until 1988.[25] Menashe Klein offers two interpretations: either it is based on Moelin's rule and women who miss a week because they were giving birth are not exempted (though all other authorities assume they are exempted) or it is based on comparison with Hanukkah candles, which some medieval authorities recommended be lit one per member of the household.[26]

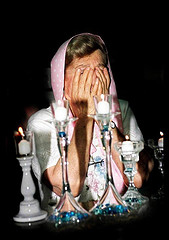

Hand waving[edit]

In the Ashkenazic rite, after the candles are lit, a blessing is said (whereas, in the Sephardic rite, the blessing is said before the lighting). In order to avoid benefiting from the light of the candles before uttering the blessing, Ashkenazic authorities recommend that the lighter cover her eyes for the intervening period.[27] Today, many Jewish women make an exaggerated motion, waving their hands in the air, when covering their eyes; there is no specific source for this in traditional texts.

The Sefer haAsuppot, attributed to the 13th-century scholar Elijah b. Isaac of Carcassonne, records that "I heard that [Rashi's granddaughter] Rabbanit Hannah, the sister of Rabbi Jacob, would warn the women not to begin the blessing until the second candle was lit, lest the women accept the Sabbath and then continue lighting candles."[28][29]

Time[edit]

The candles must be lit before the official starting time of Shabbat, which varies from place to place, but is generally 18 or 20 minutes before sunset. In some places the customary time is earlier: 30 minutes before sunset in Haifa and 40 minutes in Jerusalem, perhaps because the mountains in those cities obstructed the horizon and once made it difficult to know if sunset had arrived.

Blessing[edit]

| Hebrew | Transliteration | English |

|---|---|---|

| בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה', אֱ-לֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו, וְצִוָּנוּ לְהַדְלִיק נֵר שֶׁל שַׁבָּת. | Barukh ata Adonai Eloheinu, Melekh ha'olam, asher kid'shanu b'mitzvotav v'tzivanu l'hadlik ner shel Shabbat. | Blessed are You, LORD our God, King of the universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to light the Shabbat lamp. |

In the late 20th century, some apparently began to add the word kodesh ("holy") at the end of the blessing, making "... the lamp of holy Shabbat", a practice with no historical antecedent. At least two earlier sources include this version, the Givat Shaul of Saul Abdullah Joseph (Hong Kong, 1906)[30] and the Yafeh laLev of Rahamim Nissim Palacci (Turkey, 1906)[31] but authorities in the major Orthodox traditions were solicited for responsa only in the late 1960s, and each acknowledges it only as a new and alternative practice. Menachem Mendel Schneerson and Moshe Sternbuch endorsed the innovation[32] but most authorities, including Yitzhak Yosef, ruled that it is forbidden, though it does not nullify the blessing if already performed.[33] Almog Levi attributes this addition to misinformed baalot teshuva.[34] It has never been a widespread custom but its popularity, especially within Chabad, continues to grow.

References[edit]

- ^ Shabbat Candles, Feminine Light

- ^ Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayim 263:2

- ^ [1]Jewish Virtual Library, Shabbat

- ^ "Arukh HaShulchan, Orach Chaim 263:5". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ "Midrash Lekach Tov, Exodus 35:3:3". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ "Bereshit Rabbah 60:16". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ "HebrewBooks.org Sefer Detail: חקרי לב - חלק ד -- לנדסברג, יהודה ליב בן ישראל איצק אהרן, 1848-1915". hebrewbooks.org. p. 82ff. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ a b c d e Lauterbach, Jacob Zallel (1951). Rabbinic Essays. Hebrew Union College Press. ISBN 978-0-608-14972-1.

- ^ "Rashi on Shabbat 25b:3:3". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ סדר התפלות מכל השנה: כמנהג פולין, עם פרשיות ... יוצרות, סליחות, הושענות, מערבית, יום כיפור קטן, תהלים, תחינות, אקוראהט כמו דיא מר' ישראל גר ... [וגם] כוונת הפייטן אויף טייטש ... (in Hebrew). דפוס יוסף ויעקב בני אברהם פרופס. 1766.

- ^ The Jewish Review. Geo. Routledge & Sons. 1910.

- ^ Jerusalem Talmud, Shabbat 2:6; Genesis Rabbah 17:8, Tanhuma (Buber) Noah 1:1

- ^ Talmud, Shabbat 32a s.v. hareni

- ^ Shapiro, Marc B. (2008). "Maimonidean Halakhah and Superstition". Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters. University of Scranton Press. p. 136. ISBN 1-58966-165-6.

- ^ "Mishneh Torah, Sabbath 5:3". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ "Arukh HaShulchan, Orach Chaim 263:5". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ "Rosh Hashanah 27a:2". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ ספר ראבי"ה סי' קצט

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chayim 263:1". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ "Ba'er Hetev on Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chayim 263:2". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ "Mishnah Berurah 263:6". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ "Mishnah Berurah 263:7". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ "לקוטי מהרי"ח - חלק ב - פרידמן, ישראל חיים בן יהודה, 1852-1922 (page 29 of 201)". hebrewbooks.org. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ Likkutei Sichot, vol. 11, p. 289 (1998)

- ^ "ספר גדולת מרדכי : סיפורים ושיחות ... מהרב ... מרדכי מנדבורנא-בושטינא ; וספר קדושת ישראל : תולדות ואורחות חיים ... מבנו ... ר' ישראל יעקב מחוסט / [היו לאחדים בידי והוצאתים לאור ברוך מאיר קליין מדעברעצין] | קליין, ברוך מאיר | | הספרייה הלאומית". www.nli.org.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- ^ "HebrewBooks.org Sefer Detail: משנה הלכות חלק ז -- מנשה קליין". hebrewbooks.org. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chayim 263:5". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ בר-לבב, Liora Elias Bar-Levav (1966-2006) ליאורה אליאס. "מנהג יפה הוא לנשים שלנו : פסיקת הלכה על פי נשים בימי הביניים".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "ספר האסופות". www.nli.org.il. p. 77a. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ p. 251

- ^ p. 127

- ^ Igrot Qodesh of 5735 p. 208; Tshuvot v'Hanhagot 1:271

- ^ Yalkut Yosef 263:51

- ^ M'Torato shel Maran p. 80

- ^ Lauterbach claims (p. 456 and p. 458) that such was the Samaritan custom, but cites only sources describing Karaitic practice regarding light and Samaritan custom regarding the cooking of food. According to Geiger and Zunz (op cit.), the Sadducees held to this view, as shown by the (arguably) polemical tone in Midrash Tanchuma וקראת לשבת עונג זו הדלקת נר בשבת וא"ת לישב בחשך אין זו עונג שאין יורדי גיהנם נדונין אלא בחשך.

- ^ Herod personifies the Jewish people; his "day" is the Sabbath. See Menachem Stern, Greek and Latin Authors vol. 1 p. 436; also Molly Whittaker, Jews and Christians vol. 6 p. 71. In Morton-Braund's edition (2004), pg. 110-113.

- ^ Maimonides frowns on women leaving home more than once a month. (Ishut 13:11)

- ^ Elijah Spira writes (1757) that "some say that the lamps represent man and woman, as ner (lamp) in gematriya is 250, and a man has 248 bones while a woman has 252." However, this explanation is intended abstractly and Spira does not imagine that anyone should light more lamps to correspond to a larger family.

Further reading[edit]

- B.M. Lewin, The History of the Sabbath Candles, in Essays and Studies in Memory of Linda A. Miller, I. Davidson (ed), New York, 1938, pp.55-68.