Alcoholic hepatitis

| Alcoholic hepatitis | |

|---|---|

| |

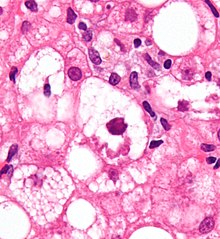

| Micrograph showing a Mallory body, a histopathologic finding associated with alcoholic hepatitis. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Complications | Cirrhosis, Kidney failure, Confusion, drowsiness and slurred speech (hepatic encephalopathy), Ascites, Enlarged veins (varices).[1] |

| Risk factors | Sex, Obesity, Genetic factors, Race and ethnicity, Binge drinking.[1] |

Alcoholic hepatitis is hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) due to excessive intake of alcohol.[2] Patients typically have a history of at least 10 years of heavy alcohol intake, typically 8–10 drinks per day.[3] It is usually found in association with fatty liver, an early stage of alcoholic liver disease, and may contribute to the progression of fibrosis, leading to cirrhosis. Symptoms may present acutely after a large amount of alcoholic intake in a short time period, or after years of excess alcohol intake. Signs and symptoms of alcoholic hepatitis include jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity), fatigue and hepatic encephalopathy (brain dysfunction due to liver failure).[3] Mild cases are self-limiting, but severe cases have a high risk of death. Severity in alcoholic hepatitis is determined several clinical prediction models such as the Maddrey's Discriminant Function and the MELD score.

Severe cases may be treated with glucocorticoids with a response rate of about 60%. The condition often comes on suddenly and may progress in severity very rapidly.

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Alcoholic hepatitis is characterized by a number of symptoms, which may include feeling unwell, enlargement of the liver, development of fluid in the abdomen (ascites), and modest elevation of liver enzyme levels (as determined by liver function tests).[4] It may also present with Hepatic encephalopathy (brain dysfunction due to liver failure) causing symptoms such as confusion, decreased levels of consciousness, or asterixis,[5] (a characteristic flapping movement when the wrist is extended indicative of hepatic encephalopathy). Severe cases are characterized by profound jaundice, obtundation (ranging from drowsiness to unconsciousness), and progressive critical illness; the mortality rate is 50% within 30 days of onset despite best care.[3]

Alcoholic hepatitis is distinct from cirrhosis caused by long-term alcohol consumption. Alcoholic hepatitis can occur in patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease and alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcoholic hepatitis by itself does not lead to cirrhosis, but cirrhosis is more common in patients with long term alcohol consumption.[6] Some alcoholics develop acute hepatitis as an inflammatory reaction to the cells affected by fatty change.[6] This is not directly related to the dose of alcohol. Some people seem more prone to this reaction than others. This inflammatory reaction to the fatty change is called alcoholic steatohepatitis and the inflammation probably predisposes to liver fibrosis by activating hepatic stellate cells to produce collagen.[6]

Pathophysiology[edit]

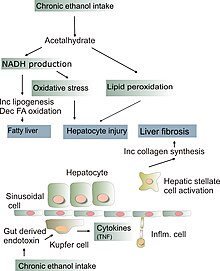

The pathological mechanisms in alcoholic hepatitis are incompletely understood but a combination of direct hepatocyte damage by alcohol and its metabolites in addition to increased intestinal permeability are thought to play a role.[7] Heavy alcohol consumption increases intestinal permeability by causing direct damage to enterocytes (intestinal absorptive cells) and causing disruptions of tight junctions that form a barrier between the enterocytes.[7] This leads to increased intestinal permeability which then leads to pathogenic gut bacteria (such as enterococcus faecalis) or immunogenic fungi entering the portal circulation, and travelling to the liver where they cause hepatocyte damage.[7] In the case of enterococcus faecalis, the bacterium can release an exotoxin which is directly damaging to liver cells.[7] Chronic alcohol consumption may alter the gut microbiome and promote the production of these pathogenic bacteria.[7] Many of these pathogenic bacteria also contain Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs), extracellular motifs that are recognized by the immune system as foreign material, which may lead to an exaggerated inflammatory response in the liver which further leads to hepatocyte damage.[7]

Alcohol is also directly damaging to liver cells. Alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde in the liver via the enzymes CYP2E1 and aldehyde dehydrogenase.[7] Acetaldehyde forms reactive oxygen species in the liver as well as acting as a DNA adduct (binding to DNA) leading to direct hepatocyte damage.[7] This manifests as lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial damage, and glutathione (an endogenous antioxidant) depletion.[7] Damaged hepatocytes release Danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) which are molecules that lead to further activation of the immune system's inflammatory response and further hepatocyte damage.[7]

The chronic inflammation seen in alcoholic hepatitis leads to a distinctive fibrotic response, with fibrogenic cell type activation. This occurs via an increased extracellular matrix deposition around hepatocytes and sinusoidal cells which causes a peri-cellular fibrosis known as "chickenwire fibrosis".[7] This peri-cellular chickenwire fibrosis leads to portal hypertension or an elevated blood pressure in the portal veins that drain blood from the intestines to the liver.[7] This causes many of the sequelae of chronic liver disease including esophageal varices (with associated variceal bleeding), ascites and splenomegaly.

The chronic inflammation seen in alcoholic hepatitis also leads to impaired hepatocyte differentiation, impairments in hepatocyte regeneration and hepatocyte de-differentiation into cholangiocyte type cells.[7] This leads to defects in the liver's many functions including impairments in bilirubin transport, clotting factor synthesis, glucose metabolism and immune dysfunction.[7] This impaired compensatory liver regenerative response further leads to a ductular reaction; a type of abnormal liver cell architecture.[7]

Due to the release of DAMPs and PAMPs, an acute systemic inflammatory state can develop after extensive alcohol intake that dominates the clinical landscape of acute severe alcoholic hepatitis. IL-6 has been shown to have the most robust increase among pro-inflammatory mediators in these patients. Furthermore, decreased levels of IL-13, an antagonistic cytokine of IL-6 was found to be closely associated with short-term (90-day) mortality in severe alcoholic hepatitis patients.[8]

Some signs and pathological changes in liver histology include:

- Mallory's hyaline body – a condition where pre-keratin filaments accumulate in hepatocytes. This sign is not limited to alcoholic liver disease, but is often characteristic.[6]

- Ballooning degeneration – hepatocytes in the setting of alcoholic change often swell up with excess fat, water and protein; normally these proteins are exported into the bloodstream. Accompanied with ballooning, there is necrotic damage. The swelling is capable of blocking nearby biliary ducts, leading to diffuse cholestasis.[6]

- Inflammation – neutrophilic invasion is triggered by the necrotic changes and presence of cellular debris within the lobules. Ordinarily the amount of debris is removed by Kupffer cells, although in the setting of inflammation they become overloaded, allowing other white cells to spill into the parenchyma. These cells are particularly attracted to hepatocytes with Mallory bodies.[6]

If chronic liver disease is also present:

Epidemiology[edit]

- Alcoholic hepatitis occurs in approximately 1/3 of chronic alcohol drinkers.[9]

- 10-20% of patients with alcoholic hepatitis progress to alcoholic liver cirrhosis every year.[10]

- Patients with liver cirrhosis develop liver cancer at a rate of 1.5% per year.[11]

- In total, 70% of those with alcoholic hepatitis will go on to develop alcoholic liver cirrhosis in their lifetimes.[10]

- Infection risk is elevated in patients with alcoholic hepatitis (12–26%). It increases even higher with use of corticosteroids (50%)[12] when compared with the general population.

- Untreated alcoholic hepatitis mortality in one month of presentation may be as high as 40-50%.[4]

Diagnosis[edit]

The diagnosis is made in a patient with history of significant alcohol intake who develops worsening liver function tests, including elevated bilirubin (typically greater than 3.0) and aminotransferases, and onset of jaundice within the last 8 weeks.[3] The ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase is usually 2 or more.[13] In most cases, the liver enzymes do not exceed 500. A liver biopsy is not required for the diagnosis, however it can help confirm alcoholic hepatitis as the cause of the hepatitis if the diagnosis is unclear.[3][14]

Management[edit]

Clinical practice guidelines have recommended corticosteroids.[15]

People should be risk stratified using a MELD Score or Child-Pugh score. These scores are used to evaluate the severity of the liver disease based on several lab values. The greater the score, the more severe the disease.

- Abstinence: Stopping further alcohol consumption is the number one factor for recovery in patients with alcoholic hepatitis.[16]

- Nutrition Supplementation: Protein and calorie deficiencies are seen frequently in patients with alcoholic hepatitis, and it negatively affects their outcomes. Improved nutrition has been shown to improve liver function and reduce incidences encephalopathy and infections.[4]

- Corticosteroids: These guidelines suggest that patients with a modified Maddrey's discriminant function score > 32 or hepatic encephalopathy should be considered for treatment with prednisolone 40 mg daily for four weeks followed by a taper.[15] Models such as the Lille Model can be used to monitor for improvement or to consider alternative treatment.

- Pentoxifylline: Systematic reviews comparing the treatment of pentoxifylline with corticosteroids show there is no benefit to treatment with pentoxifylline[4] Potential for combined therapy: A large prospective study of over 1000 patients investigated whether prednisolone and pentoxifylline produced benefits when used alone or in combination.[17] Pentoxifylline did not improve survival alone or in combination. Prednisolone gave a small reduction in mortality at 28 days but this did not reach significance, and there were no improvements in outcomes at 90 days or 1 year.[4]

- Intravenous N-acetylcysteine: When used in conjunction with corticosteroids, improves survival at 28 days by decreasing rates of infection and hepatorenal syndrome.[4]

- Liver Transplantation: Early liver transplantation is ideal and helps to save lives.[18] However, most transplant providers in the United States require a period of alcohol abstinence (typically six months) prior to transplant, but the ethics and science behind this are controversial.[18]

Prognosis[edit]

Females are more susceptible to alcohol-associated liver injury and are therefore at higher risk of alcohol-associated hepatitis.[7] Certain genetic variations in the PNPLA3-encoding gene, which codes for an enzyme involved in triglyceride metabolism in adipose tissue are thought to influence disease severity.[7] Other factors in alcoholic hepatitis associated with a poor prognosis include concomitant hepatic encephalopathy and acute kidney injury.[7]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Alcoholic hepatitis". mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ "Alcoholic liver disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Im, Gene Y. (February 2019). "Acute Alcoholic Hepatitis". Clinics in Liver Disease. 23 (1): 81–98. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2018.09.005. PMID 30454835. S2CID 53873388.

- ^ a b c d e f Singal, Ashwani K.; Kodali, Sudha; Vucovich, Lee A.; Darley-Usmar, Victor; Schiano, Thomas D. (July 2016). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Systematic Review". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 40 (7): 1390–1402. doi:10.1111/acer.13108. PMC 4930399. PMID 27254289.

- ^ Amodio, Piero (June 2018). "Hepatic encephalopathy: Diagnosis and management". Liver International. 38 (6): 966–975. doi:10.1111/liv.13752. PMID 29624860.

- ^ a b c d e f Cotran; Kumar, Collins (1998). Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: W.B Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-7335-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bataller, Ramon; Arab, Juan Pablo; Shah, Vijay H. (29 December 2022). "Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 387 (26): 2436–2448. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2207599. PMID 36577100. S2CID 255251817.

- ^ Tornai, David; Mitchell, Mack; McClain, Craig J.; Dasarathy, Srinivasan; McCullough, Arthur; Radaeva, Svetlana; Kroll-Desrosiers, Aimee; Lee, JungAe; Barton, Bruce; Szabo, Gyongyi (December 2023). "A novel score of IL-13 and age predicts 90-day mortality in severe alcohol-associated hepatitis: A multicenter plasma biomarker analysis". Hepatology Communications. 7 (12). doi:10.1097/HC9.0000000000000296. PMC 10666984.

- ^ Barrio, E.; Tomé, S.; Rodríguez, I.; Gude, F.; Sánchez-Leira, J.; Pérez-Becerra, E.; González-Quintela, A. (January 2004). "Liver Disease in Heavy Drinkers With and Without Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome". Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 28 (1): 131–136. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000106301.39746.EB. ISSN 0145-6008. PMID 14745311.

- ^ a b Fleming, Kate M.; Aithal, Guruprasad P.; Card, Tim R.; West, Joe (January 2012). "All-cause mortality in people with cirrhosis compared with the general population: a population-based cohort study: Cirrhosis mortality" (PDF). Liver International. 32 (1): 79–84. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02517.x. PMID 21745279. S2CID 43829150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ Schwartz, Jonathan M.; Reinus, John F. (November 2012). "Prevalence and Natural History of Alcoholic Liver Disease". Clinics in Liver Disease. 16 (4): 659–666. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.001. PMID 23101975. S2CID 25687227.

- ^ Louvet, Alexandre; Wartel, Faustine; Castel, Hélène; Dharancy, Sébastien; Hollebecque, Antoine; Canva–Delcambre, Valérie; Deltenre, Pierre; Mathurin, Philippe (August 2009). "Infection in Patients With Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis Treated With Steroids: Early Response to Therapy Is the Key Factor". Gastroenterology. 137 (2): 541–548. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.062. ISSN 0016-5085. PMID 19445945.

- ^ Sorbi D, Boynton J, Lindor KD (1999). "The ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase: potential value in differentiating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from alcoholic liver disease". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94 (4): 1018–22. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01006.x. PMID 10201476. S2CID 23116073.

- ^ Keating, Michelle; Lardo, Olivia; Hansell, Maggie (1 April 2022). "Alcoholic Hepatitis: Diagnosis and Management". American Family Physician. 105 (4): 412–420. PMID 35426628.

- ^ a b Crabb, DW; Im, Gene Young (2020-01-01). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol‐Associated Liver Diseases: 2019 Practice Guidance From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases". Hepatology. 71 (1): 306–333. doi:10.1002/hep.30866. PMID 31314133.

- ^ Louvet, Alexandre; Labreuche, Julien; Artru, Florent; Bouthors, Alexis; Rolland, Benjamin; Saffers, Pierre; Lollivier, Julien; Lemaître, Elise; Dharancy, Sébastien; Lassailly, Guillaume; Canva-Delcambre, Valérie (26 September 2017). "Main drivers of outcome differ between short term and long term in severe alcoholic hepatitis: A prospective study". Hepatology. 66 (5): 1464–1473. doi:10.1002/hep.29240. ISSN 0270-9139. PMID 28459138.

- ^ Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, Downs N, Gleeson D, MacGilchrist A, Grant A, Hood S, Masson S, McCune A, Mellor J, O'Grady J, Patch D, Ratcliffe I, Roderick P, Stanton L, Vergis N, Wright M, Ryder S, Forrest EH (2015). "Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 372 (17): 1619–28. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1412278. PMID 25901427. S2CID 205097413.

- ^ a b Im, Gene; Cameron, Andrew (2019). "Liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis". Journal of Hepatology. 70 (2): 328–334. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.11.007. PMID 30658734.