Russian cursive

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (November 2018) |

Russian cursive is a variant of the Russian alphabet used for writing by hand. It is typically referred to as (ру́сский) рукопи́сный шрифт (rússky) rukopísny shrift, "(Russian) handwritten font". It is the handwritten form of the modern Russian Cyrillic script, used instead of the block letters seen in printed material. In addition, Russian italics for lowercase letters are often based on Russian cursive (such as lowercase т, which resembles Latin m). Most handwritten Russian, especially in personal letters and schoolwork, uses the cursive alphabet. In Russian schools most children are taught from first grade how to write with this script.

History[edit]

The Russian (and Cyrillic in general) cursive was developed during the 18th century on the base of the earlier Cyrillic tachygraphic writing (ско́ропись, skoropis, "rapid or running script"), which in turn was the 14th–17th-century chancery hand of the earlier Cyrillic bookhand scripts (called ustav and poluustav). It became the handwritten counterpart of so-called "civil" (or Petrine) printed script of books. In order[clarification needed], modern Cyrillic italic typefaces are based (in their lowercase part) mostly on the cursive shape of the letters.

The resulting cursive bears many similarities with the Latin cursive.[1] For example, the modern Russian cursive letter "п" may coincide with Latin cursive "n" (𝓃) (despite having completely different sound values); both upright and italic printed typefaces demonstrate less similarity.

One must not confuse the historical Russian chancery hand (ско́ропись, skóropis' ), the contemporary Russian cursive (рукопи́сное письмо́, rukopísnoe pis'mó) and the contemporary Russian stenography. The latter is completely different from the other two, though it is sometimes called ско́ропись, skóropis' , like the former.

Features[edit]

Russian cursive is much like contemporary English and other Latin cursives. But unlike Latin handwriting, which can range from fully cursive to heavily resembling the printed typefaces and where idiosyncratic mixed systems are most common, it is standard practice to write in Russian cursive almost exclusively.

Ambiguities[edit]

There exists some ambiguity from the fact that several lowercase cursive letters consist (entirely or in part) of the element that is identical to the dotless Latin cursive letter ı, the cursive Greek letter ι or a half of the cursive letter u, namely и, л, м, ш, щ, ы. Therefore, certain combinations of these Russian letters cannot be unambiguously deciphered without knowing the language or without a broader context. For example, in the words волшебник, "magician" and домик, "little house" the combinations лш and ми are written identically. The word лишишь, "you will deprive" written in cursive consists almost exclusively of these elements. There are examples of different words that become absolutely identical in their cursive form, e.g. мщу "I avenge" and лицу (dative of лицо "face"). The most radical form of this, though not well known, is the Tajik word миллии meaning 'national'. It consists only of these elements.

Some words in Russian may pose a challenge due to the similarities between the letters Ш, Щ, И, Л, М in cursive.

Variants, use of diacritics[edit]

In some forms of cursive, the distinction between т and ш may become elusive because both are written in the shapes of either m or ɯ. To alleviate this case of ambiguity, a horizontal bar can be written above the character (like m̅ or rarely ɯ̅) if it is т, or below (like ɯ̲ or rarely m̲) if it is ш. Also, writing т in its printed form (the T shape) rather than its usual m shape is common.

The letter д may also be written in the shape of ꝺ or ∂.

Differences to Serbian and Macedonian cursives[edit]

Several letters in Russian cursive are different from the cursive used in the Serbian and Macedonian languages. Thus, Serbian/Macedonian cursive lowercase г looks the same as in Russian with additional macron, п is written like the cursive Latin u with macron (ū), and the letter т is written in the shape of ɯ̅.[2][3]

Charts[edit]

-

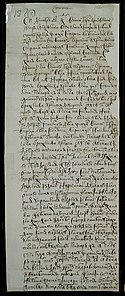

Varieties of Russian calligraphic cursive from an 1835 dictionary

-

Pre-reform Russian calligraphic cursive from a 1916 schoolbook

-

Modern cursive taught in schools

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Белоконь, Е. А. (2001). Характеристика почерков XVIII-XIX вв. и термины в описаниях собраний рукописей [Characteristic handwriting XVIII-XIX centuries. and terms in descriptions of manuscript collections]. Вспомогательные исторические дисциплины: специальные функции и гуманитарные перспективы ; тезисы докладов и сообщений XIII научной конференции [Auxiliary Historical Disciplines: Special Functions and Humanitarian Perspectives; Abstracts of Reports and Communications of the XIII Scientific Conference] (in Russian). Moscow.

Термины «скоропись» и «курсив» в русской палеографии применяются параллельно, в то же время, в развитии русской скорописи намечаются тенденции, позволяющие выделить новый тип письма, схожий с латинским курсивным письмом, близким к современному. Если в частной сфере применения и в каллиграфии быстрее произошел переход к использованию курсивного письма, то в делопроизводственной традиции эти типы письма довольно долго сосуществовали.

≈ "Terms 'tachygraphy' and 'cursive' coexist in the Russian palaeography; meanwhile, in the development of the Russian tachygraphy there are tendencies that allow us to separate a new type of writing, one closer to the Latin cursive similar to its modern form. In the private sphere and in calligraphy, transition to the cursive writing occurred faster, but in the tradition of record keeping, these types of writing coexisted for a long time.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Peshikan, Mitar; Jerković, Jovan; Pižurica, Mato (1994). Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd: Matica Srpska. p. 42. ISBN 86-363-0296-X.

- ^ Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (PDF). Skopje: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov. 2017. p. 3. ISBN 978-608-220-042-2.