Prince William, Duke of Gloucester

| Prince William | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke of Gloucester | |||||

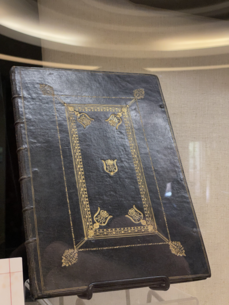

Portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller, c. 1700 | |||||

| Born | 24 July 1689 Hampton Court Palace, London, England | ||||

| Died | 30 July 1700 (aged 11) Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire, England | ||||

| Burial | 9 August 1700 | ||||

| |||||

| House | Oldenburg | ||||

| Father | Prince George of Denmark | ||||

| Mother | Anne Stuart (later Anne, Queen of Great Britain) | ||||

Prince William, Duke of Gloucester (William Henry; 24 July 1689 – 30 July 1700[a]), was the son of Princess Anne (later Queen of England, Ireland and Scotland from 1702) and her husband, Prince George of Denmark. He was their only child to survive infancy. Styled Duke of Gloucester, he was viewed by contemporaries as a Protestant champion because his birth seemed to cement the Protestant succession established in the "Glorious Revolution" that had deposed his Catholic grandfather James II & VII the previous year.

Anne was estranged from her brother-in-law and cousin, William III & II, and her sister, Mary II, but supported links between them and her son. He grew close to his uncle William, who created him a Knight of the Garter, and his aunt Mary, who frequently sent him presents. At his nursery in Campden House, Kensington, he befriended his Welsh body-servant, Jenkin Lewis, whose memoir of the Duke is an important source for historians, and operated his own miniature army, called the "Horse Guards", which eventually comprised 90 boys.

Gloucester's precarious health was a constant source of worry to his mother. His death in 1700 at the age of 11 precipitated a succession crisis as his mother was the only individual remaining in the Protestant line of succession established by the Bill of Rights 1689. The English Parliament did not want the throne to revert to a Catholic, and so passed the Act of Settlement 1701, which settled the throne of England on Electress Sophia of Hanover, a cousin of King James II & VII, and her Protestant heirs.

Birth and health[edit]

In late 1688, in what became known as the Glorious Revolution, the Catholic James II and VII was deposed by his Protestant nephew and son-in-law, Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange. William and his wife, James's elder daughter Mary, were recognised by the English and Scottish parliaments as king and queen. As they had no children, Mary's younger sister, Anne, was designated their heir presumptive in England and Scotland.[1] The accession of William and Mary and the succession through Anne were enshrined in the Bill of Rights 1689.[2]

Anne was married to Prince George of Denmark, and in their first six years of marriage Anne had been pregnant six times, which ended with two stillbirths, two miscarriages, and two baby daughters who died of smallpox in 1687 shortly after Anne’s first miscarriage. Her seventh pregnancy resulted in the birth of a son at 5 a.m. on 24 July 1689 in Hampton Court Palace. As it was usual for the births of potential heirs to the throne to be attended by several witnesses, the King and Queen and "most of the persons of quality about the court" were present.[3] Three days later, the newborn baby was baptised William Henry after his uncle King William by Henry Compton, Bishop of London. The King, who was one of the godparents along with the Marchioness of Halifax[4] and the Lord Chamberlain, Lord Dorset,[5] declared him Duke of Gloucester,[6] although the peerage was never formally created.[7] Gloucester was second in line to the throne after his mother, and because his birth secured the Protestant succession, he was the hope of the revolution's supporters.[8] The ode The Noise of Foreign Wars, attributed to Henry Purcell, was written in celebration of the birth.[9] Other congratulatory odes, such as Purcell's last royal ode Who Can From Joy Refrain? and John Blow's The Duke of Gloucester's March and A Song upon the Duke of Gloucester, were composed for his birthdays in later years.[10][11] Opponents of the revolution, supporters of James known as the Jacobites, spoke of Gloucester as "a sickly and doomed usurper".[8]

Though described as a "brave livlylike [sic] boy",[12] Gloucester became ill with convulsions when he was three weeks old, so his mother moved him into Craven House, Kensington, hoping that the air from the surrounding gravel pits would have a beneficial effect on his health.[13] His convulsions were possibly symptomatic of meningitis, likely contracted at birth and which resulted in hydrocephalus.[14] As was usual among royalty, Gloucester was placed in the care of a governess, Lady Fitzhardinge,[15] and was suckled by a wet nurse, Mrs. Pack, rather than his mother.[b] As part of his treatment, Gloucester was driven outside every day in a small open carriage, pulled by Shetland ponies, to maximise his exposure to the air of the gravel pits.[18] When the effectiveness of this treatment exceeded their expectations, Princess Anne and her husband acquired a permanent residence in the area, Campden House, a Jacobean mansion, in 1690.[19] It was here that Gloucester befriended Welsh body-servant Jenkin Lewis, whose memoir of his master is an important source for historians.[20]

Throughout his life, Gloucester had a recurrent "ague", which was treated with regular doses of Jesuit's bark (an early form of quinine) by his physician, John Radcliffe. Gloucester disliked the treatment intensely, and usually vomited after being given it.[21] Possibly as a result of hydrocephalus,[22][14] he had an enlarged head, which his surgeons pierced intermittently to draw off fluid.[23] He could not walk properly, and was apt to stumble.[22] Nearing the age of five, Gloucester refused to climb stairs without two attendants to hold him, which Lewis blamed on indulgent nurses who over-protected the boy. His father birched him until he agreed to walk by himself.[24] Corporal punishment was usual at the time, and such treatment would not have been considered harsh.[25]

Education[edit]

Gloucester's language acquisition was delayed; he did not speak correctly until the age of three,[26] and consequently the commencement of his education was postponed by a year.[27] The Reverend Samuel Pratt, a Cambridge graduate, was appointed the Duke's tutor in 1693.[15] Lessons concentrated on geography, mathematics, Latin, and French.[17] Pratt was an enemy of Jenkin Lewis, and they frequently disagreed over how Gloucester should be educated.[15] Lewis remained Gloucester's favourite attendant because, unlike Pratt, he was knowledgeable in military matters and could therefore help him with his "Horse Guards",[28] a miniature army consisting of local children.[29] Over a couple of years from 1693, the size of the army grew from 22 to over 90 boys.[30]

Princess Anne had fallen out with her sister and brother-in-law, William and Mary, and reluctantly agreed to the advice of her friend, the Countess of Marlborough, that Gloucester should visit his aunt and uncle regularly to ensure their continued goodwill towards him.[31] In an attempt to heal the rift, Anne invited the King and Queen to see Gloucester drill the "Horse Guards".[32] After watching the boys' display at Kensington Palace, the King praised them, and made a return visit to Campden House the following day.[33] Gloucester grew closer to his aunt and uncle: the Queen bought him presents from his favourite toy shop regularly.[34] Her death in 1694 led to a superficial reconciliation between Anne and William, which occasioned a move to St James's Palace, London.[35] Gloucester having tired of him, Lewis only attended St James's every two months.[36]

On his seventh birthday, Gloucester attended a ceremony at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, to install him as a knight of the Order of the Garter, an honour the King had given him six months before. Gloucester became ill during the celebratory banquet afterwards and left early, but after his recovery went deer hunting in Windsor Great Park, where he was blooded by Samuel Masham, his father's page.[37] Princess Anne wrote to the Countess of Marlborough, "My boy continues yet very well, and looks better, I think, than ever he did in his life; I mean more healthy, for though I love him very well, I can't brag of his beauty."[37]

During the trial of Sir John Fenwick, who was implicated in a plot to assassinate King William,[38] Gloucester signed a letter to the King promising his loyalty. "I, your Majesty's most dutiful subject," the letter read, "had rather lose my life in your Majesty's cause than in any man's else, and I hope it will not be long ere you conquer France."[39] Added to the letter was a declaration by the boys in Gloucester's army: "We, your Majesty's subjects, will stand by you while we have a drop of blood."[39]

In 1697, Parliament granted King William £50,000 to establish a household for the Duke of Gloucester, though the King only permitted the release of £15,000, keeping the difference for himself.[40] The establishment of Gloucester's own household in early 1698 revived the feud between Anne and William.[41] William was determined to limit Anne's involvement in the household, and therefore appointed, against her wishes, the low church Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury, as Gloucester's preceptor.[42] Anne was high church,[43] and Burnet, knowing she was unhappy, attempted to decline the appointment, but the King insisted he accept it.[44] Anne's anger was only placated by an assurance from King William that she could choose all the lower servants of the household.[45] The Earl of Marlborough, a friend of Anne's, was appointed Gloucester's governor, after the Duke of Shrewsbury declined the office on the grounds of ill health.[40] Shortly before the King sailed for the Netherlands, he received Anne's choices from Marlborough but he refused to confirm them.[45] His favourite, the Earl of Albemarle, eventually convinced him to agree to Anne's appointments, and the King's acceptance was sent from the Netherlands in September 1698.[46] The Marlboroughs' twelve-year-old son, Lord Churchill, was appointed Gloucester's Master of the Horse, and became a friend and playmate.[47] Abigail Hill, a kinswoman of the Countess of Marlborough, was appointed his laundress, and Abigail's brother, Jack Hill, was made one of Gloucester's gentlemen of the bedchamber.[48]

Burnet lectured Gloucester for hours at a time on subjects such as the feudal constitutions of Europe and law before the time of Christianity.[49] Burnet also encouraged Gloucester to memorise facts and dates by heart.[49] Government ministers inspected Gloucester's academic progress every four months, finding themselves "amazed" by his "wonderful memory and good judgement".[49] His childhood troop was disbanded, and King William made him the honorary commander of a real regiment of Dutch footguards.[50] In 1699, he attended the trials in the House of Lords of Lord Mohun and Lord Warwick, who were accused of murder.[30] Mohun was acquitted; Warwick was found guilty of manslaughter but escaped punishment by pleading privilege of peerage.[51]

Death[edit]

As he neared his eleventh birthday, Gloucester was assigned the rooms in Kensington Palace that had been used by his aunt, Queen Mary, who died in 1694.[30] At his birthday party at Windsor, on 24 July 1700, he complained of a sudden fatigue, but was initially thought to have overheated himself while dancing.[52] By nightfall, he had a sore throat and chills, followed by a severe headache and a high fever the next day.[52][53] A physician, Hannes, did not arrive until 27 July. Gloucester was immediately bled, but his condition continued to deteriorate. Over the next day, he developed a rash and diarrhoea. A second physician, Gibbons, arrived early on 28 July, followed by Radcliffe that evening.[53]

The physicians could not agree on a diagnosis.[52] Radcliffe thought he had scarlet fever, while others thought it was smallpox.[54] They administered "cordial powders and cordial juleps".[53] Gloucester was bled, to which Radcliffe strongly objected. He told his colleagues, "you have destroyed him and you may finish him".[54] He prescribed blistering, which was no more effective.[55] In great pain, Gloucester spent the evening of 28 July "in great sighings and dejections of spirits ... towards morning, he complained very much of his blisters."[53] Anne, who had spent an entire day and night by her son's bedside, now became so distressed that she fainted.[53] However, by midday on 29 July, Gloucester was breathing more easily and his headache had diminished, leading to hopes that he would recover. The improvement was fleeting, and that evening, he was "taken with a convulsing sort of breathing, a defect in swallowing and a total deprivation of all sense".[53] Prince William died close to 1 a.m. on 30 July 1700, with his parents beside him. In the end, the physicians decided the cause of death was "a malignant fever".[53] An autopsy revealed severe swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck and an abnormal amount of fluid in the ventricles of his brain:[56] "four and a half ounces of a limpid humour were taken out."[53] Gloucester may have died from smallpox[57] or, according to modern medical diagnosis, an acute bacterial pharyngitis, with associated pneumonia.[53][58][59] Had he lived, though, it is almost certain the prince would have succumbed to complications of his hydrocephalus.[53]

King William, who was in the Netherlands, wrote to Marlborough, "It is so great a loss to me as well as to all England, that it pierces my heart."[60] Anne was prostrate with grief, taking to her chamber.[61] In the evenings, she was carried into the garden "to divert her melancholy thoughts".[53] Gloucester's body was moved from Windsor to Westminster on the night of 1 August, and he lay in state in the Palace of Westminster before being entombed in the Royal Vault of the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey on 9 August.[62] As was usual for royalty in mourning, his parents did not attend the funeral service, instead remaining in seclusion at Windsor.[61]

In an allusion to Prince William's death, Tory politician William Shippen wrote:

So by the course of the revolving spheres,

Whene'er a new-discovered star appears,

Astronomers, with pleasure and amaze,

Upon the infant luminary gaze.

They find their heaven's enlarged, and wait from thence

Some blest, some more than common influence,

But suddenly, alas! The fleeting light,

Retiring, leaves their hopes involv'd in endless night.[63]

Gloucester's death destabilised the succession, as his mother was the only person remaining in the Protestant line to the throne established by the Bill of Rights 1689.[52] Although Anne had ten other pregnancies after the birth of Gloucester, none of them resulted in a child who survived more than briefly after birth.[64] The English parliament did not want the throne to revert to a Catholic,[65] so it passed the Act of Settlement 1701, which settled the throne of England on a cousin of King James, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, and her Protestant heirs.[66] Anne succeeded King William in 1702, and reigned until her death on 1 August 1714. Sophia predeceased her by a few weeks, and so Sophia's son George ascended the throne as the first British monarch of the House of Hanover.[67]

Titles, styles, honours and arms[edit]

William was styled as: His Royal Highness Prince William, Duke of Gloucester.[68] The title became extinct on his death.[69]

Honours[edit]

- KG: Knight of the Garter, 6 January 1696[7]

Arms[edit]

Gloucester bore the royal arms, differenced by an inescutcheon of the Danish coat of arms and a label of three points Argent, the centre point bearing a cross Gules.[70]

Ancestry[edit]

| Ancestors of Prince William, Duke of Gloucester[71] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[edit]

Informational notes

- ^ All dates in this article are in the Old Style Julian calendar in use in Britain throughout Gloucester's life; however, years are assumed to start on 1 January rather than 25 March, which was the English New Year.

- ^ Mrs Pack was said to be so ugly that she was "fitter to go to a pigsty than to a prince's bed".[16] She apparently failed to gain Gloucester's affection; on her death in 1694, he was asked by the Queen if he was sad at the news, to which he replied, "No, madam".[17]

Citations

- ^ Gregg, pp. 63–69; Somerset, pp. 98–110

- ^ Somerset, p. 109

- ^ Gregg, p. 72; Somerset, p. 113

- ^ Chapman, p. 21

- ^ Gregg, p. 72

- ^ Chapman, p. 21; Green, p. 54; Gregg, p. 72

- ^ a b Gibbs and Doubleday, p. 743

- ^ a b Chapman, p. 46

- ^ White, Bryan (Winter 2007). "Music for a 'brave livlylike boy': the Duke of Gloucester, Purcell and 'The noise of foreign wars'" The Musical Times 148 (1901): 75–83

- ^ Baldwin, Olive; Wilson, Thelma (September 1981). "Who Can from Joy Refraine? Purcell's Birthday Song for the Duke of Gloucester" The Musical Times 122 (1663): 596–599

- ^ McGuinness, Rosamund (April 1965). "The Chronology of John Blow's Court Odes" Music and Letters 46 (2): 102–121

- ^ Letter from Lord Melville to the Duke of Hamilton, 26 July 1689, quoted in Gregg, p. 76 and Waller, p. 296

- ^ Waller, p. 296

- ^ a b Somerset, p. 116

- ^ a b c Chapman, p. 49

- ^ Somerset, p. 113

- ^ a b Somerset, p. 145

- ^ Chapman, p. 31

- ^ Chapman, pp. 31–32

- ^ Gregg, p. 100

- ^ Green, p. 64

- ^ a b Green, p. 55

- ^ Chapman, pp. 30–31; Curtis, p. 74

- ^ Chapman, pp. 57, 74–75

- ^ Somerset, p. 144

- ^ Gregg, p. 100; Waller, p. 317

- ^ Chapman, p. 43

- ^ Chapman, p. 54

- ^ Brown, p. 141; Chapman, pp. 53, 59

- ^ a b c Kilburn, Matthew (2004). "William, Prince, duke of Gloucester (1689–1700)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29454. Retrieved 8 October 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Gregg, pp. 98–99

- ^ Waller, p. 320

- ^ Chapman, p. 65

- ^ Waller, p. 317

- ^ Gregg, pp. 105–107

- ^ Chapman, p. 89

- ^ a b Green, p. 74

- ^ Churchill, vol. I, p. 401

- ^ a b Churchill, vol. I, p. 446

- ^ a b Gregg, p. 114

- ^ Chapman, p. 131

- ^ Green, p. 78; Gregg, p. 115

- ^ Somerset, p. 157

- ^ Chapman, p. 133; Green, p. 78; Gregg, p. 115

- ^ a b Gregg, p. 115

- ^ Gregg, p. 116

- ^ Churchill, vol. I, p. 433

- ^ Churchill, vol. I, pp. 433–434

- ^ a b c Chapman, p. 137

- ^ Chapman, p. 134

- ^ Lovell, C. R. (October 1949). "The Trial of Peers in Great Britain" The American Historical Review 55: 69–81

- ^ a b c d Waller, p. 352

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Somerset, pp. 162–164

- ^ a b Green, p. 79

- ^ Chapman, p. 138

- ^ Gregg, p. 120

- ^ Snowden, Frank M. (2019). Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-300-19221-6.

- ^ Holmes, G. E. F.; Holmes, F. F. (2008). "William Henry, Duke of Gloucester (1689–1700), son of Queen Anne (1665–1714), could have ruled Great Britain". Journal of Medical Biography. 16 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1258/jmb.2006.006074. PMID 18463064. S2CID 207200131.

- ^ Holmes, Frederick (2003). The Sickly Stuarts: The Medical Downfall of a Dynasty. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 0-7509-3296-1.

- ^ Chapman, p. 142; Churchill, vol. I, p. 447

- ^ a b Somerset, p. 163

- ^ Chapman, pp. 143–144; Green, p. 80; Gregg, p. 120

- ^ Jacob, pp. 306–307

- ^ Green, p. 335

- ^ Starkey, p. 216

- ^ Starkey, pp. 215–216

- ^ Gregg, pp. 384, 394–397

- ^ Chapman, p. 90

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 128.

- ^ Ashmole, p. 539

- ^ Paget, pp. 110–112

Bibliography

- Ashmole, Elias (1715). The History of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. Bell, Taylor, Baker, and Collins.

- Brown, Beatrice Curtis (1929). Anne Stuart: Queen of England. Geoffrey Bles.

- Chapman, Hester (1955). Queen Anne's Son: A Memoir of William Henry, Duke of Gloucester. Andre Deutsch.

- Churchill, Winston S. (1947) [1933–34]. Marlborough: His Life and Times. George G. Harrop & Co.

- Curtis, Gila; introduced by Antonia Fraser (1972). The Life and Times of Queen Anne. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-99571-5.

- Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H. A. (1926). Complete Peerage. Volume V. St Catherine's Press.

- Green, David (1970). Queen Anne. Collins. ISBN 0-00-211693-6.

- Gregg, Edward (1980). Queen Anne. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-0400-1.

- Jacob, Giles (1723). A Poetical Register: Or, The Lives and Characters of All the English Poets. With an Account of Their Writings, Volume 1. Bettesworth, Taylor and Batley, etc.

- Paget, Gerald (1977). The Lineage & Ancestry of HRH Prince Charles, Prince of Wales. Charles Skilton. OCLC 632784640.

- Somerset, Anne (2012). Queen Anne: The Politics of Passion. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-720376-5.

- Starkey, David (2007). Monarchy: From the Middle Ages to Modernity. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-724766-0.

- Waller, Maureen (2002). Ungrateful Daughters: The Stuart Princesses Who Stole Their Father's Crown. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-79461-5.

External links[edit]

Media related to Prince William, Duke of Gloucester at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prince William, Duke of Gloucester at Wikimedia Commons- Portraits of William, Duke of Gloucester at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Samuel Pratt in the Dictionary of National Biography (Wikisource)

- 1689 births

- 1700 deaths

- 17th-century English nobility

- Anne, Queen of Great Britain

- Danish princes

- Norwegian princes

- Courtesy dukes

- Dukes of Gloucester

- House of Oldenburg in Denmark

- Garter Knights appointed by William III

- People from Kensington

- People with hydrocephalus

- British royalty and nobility with disabilities

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- Royalty who died as children

- Sons of queens regnant