Nietzschean Zionism

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: tone (sounds like high-school essay). (February 2020) |

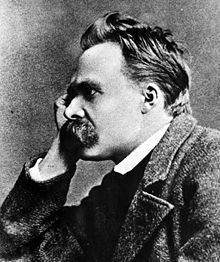

Nietzschean Zionism was a movement arising from the influence that the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche had on Zionism and several of its influential thinkers.[1] Zionism was the movement for the attainment of freedom for the Jewish people through the establishment of a Jewish state.[2] Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy was popular among Jewish intellectuals, and therefore incorporated into Zionism effortlessly.[3]

Friedrich Nietzsche's influence was expressed itself by a desire to move away from the Jewish past into an empowering future for the Hebraic New Man, the adoption of his ideas necessitating the Jews to surpass the antiquarian Jewish identity that had a rabbinical consciousness at its center.[1] The philosopher's influence on the Zionists can then be thought of as an existential revolution–that is, it focused on the renewal of the Jewish identity, the adoption of aesthetic values, and enhancing the will for life.[4] The Zionist revolution emphasized that “the new Jews," the concept of which was similar to Nietzsche's “new European man,” should choose to go to Zion or stay in Europe.[3] Theodor Herzl, “the author and the vision of the Jewish State,” viewed Zionism as the arrival of an authentic image of the Jew in a state without the idea of God or any dogmatization,[3] exhibiting a very similar format to that of Nietzsche's libertarianism or anti-dogmatism.[3]

Figures[edit]

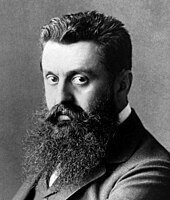

Theodor Herzl[edit]

Theodor Herzl, founder and president of the Zionist Organization, which helped establish a Jewish state, felt ambivalent about Friedrich Nietzsche's ideology, owing to Nietzsches history of mental health issues.[5][3]

Even so, Herzl's idea of the “new Jew” was profoundly similar to that of Nietzsche's “new European man” or Übermensch.[3] The character Jacob Samuel from Herzl's play Das Neue Ghetto resembles Zarathustra from Nietzsche's philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra.[3] Jacob's ideals surpass those of the herd mentality. He is proud and demonstrates no resentment, seeks to implement no values and morals, and is on a journey of overcoming his old self–Zarathustra had already displayed his ideals.[3] In Der Judenstaat, Herzl states, “If I wish to substitute a new building for an old one, I must demolish before I construct.” Nietzsche originally in On The Genealogy of Morals states, “If a temple is to be erected, a temple must be destroyed.”[3] Hence, Nietzsche's ideology on a journey toward authenticity may have heavily influenced Herzl in both his novels and personal life.[3]

Herzl refers to Plato, Arthur Schopenhauer, Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Aristotle, Ludwig Feuerbach, Franz Brentano, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling in his Jugendtagebuch.[3] Also, in his diary he quotes several Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Immanuel Kant.[3] Nietzsche was not mentioned in either case. Also, Nietzsche's “European man” could not be generalized to the situation of the Jews in Europe.[3] Since the Jewish population was unable to assimilate and prosper in Europe, Herzl then believed that the Jew could reach authenticity elsewhere, namely in Zion.[3] If so, his ideology does not align with Nietzsche's “European man”, as Nietzsche's purpose is to surpass values and morals, not to move elsewhere to find authenticity.[3] Even though Nietzsche may have influenced Herzl's ideals, he may have been a temporary scaffold into creating the image of genuine authenticity.[3]

Buber[edit]

Martin Buber, who is claimed to be responsible for incorporating Friedrich Nietzsche into German Zionism, thought that Nietzsche portrayed the role of an individual able to create and go beyond himself.[6] This he believed to be necessary for the Jewish renaissance.[7] The two thousand years of the Jewish diaspora, Buber maintained, transformed physical energy into spiritual energy within the Jews.[4] The essential drive of the Jewish renaissance was to release the spiritual energy–something that Nietzsche wrote extensively on, believing that conserving the spirit internalizes one's instincts which are then turned against oneself.[4] Nietzsche thought the correct action to take after de-spiritualization is to advance one's aesthetic drive.[4] This, in turn, was a consequence of the Jewish renaissance.[4] In relation to Buber, he created an exhibition of contemporary Jewish art.[4] Buber's vision emphasized the notion of reconciling the Jewish people to a life of creativeness, happiness, and healthiness.[4] These values that Buber believed in may have been influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche's aesthetic work The Birth of Tragedy.[8] Buber was well aware that Nietzsche used the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer to mold his authentic self; likewise, Buber used Nietzsche for the same reason.[4] Buber, after reaching and understanding the personal authenticity that Nietzsche extensively emphasized, jettisoned the philosopher from his life, as Buber believed that for one to grow truly fond of Nietzsche one must desert him.[4]

Chaim Weizmann[edit]

Chaim Weizmann, leader of the Zionist movement and future first president of the State of Israel, was influenced by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche,[9] believing that the Jews lacked power and seeing in Zionism a phenomenon that would steer the Jews toward power and freeing themselves.[10] Whether Weizmann's intention was conscious or not, his ideas relate to Nietzsche's idea of Übermensch. Although he believed that the Jews contained sufficient intellect to understand and incorporate the writings of Nietzsche into their lives, Weizmann believed this could not be done by all people.[10]

Max Nordau[edit]

Max Nordau, cofounder of the Zionist Organization, was uncertain about Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy.[11] Nietzsche received his first detailed critique from Nordau himself, although most of the arguments were against Nietzsche's character and not so much against his ideology.[4] His critique against Friedrich Nietzsche focused much on the philosopher's mental health, since Nietzsche suffered from syphilis.[4] Nietzsche's followers were also critiqued by Nordau.[4] He believed that they were “imbecile criminals” and a group of “simpletons.”[4] Lastly, Nordau found it unfortunate that the “manic” German philosopher was even considered a philosopher in the first place.[4]

Nordau, unlike Nietzsche, esteemed the values of the Enlightenment, whereas Nietzsche wanted to reevaluate values that the Enlightenment did not have in its agenda.[4] Much of Nordau's ideas resembled ideas from Nietzsche's text, namely the enrichment and expansion of European culture.[4]

Over time, Max Nordau began to self reflect on his inauthentic Jewish marginality.[4] He later dropped his Enlightenment ideals since they clashed with those of Zionism, as Zionism was a particularist movement, while The Enlightenment was a universal one.[4] His inauthentic Jewish marginality would then become an authentic one when taking up Zionist thinking.[4] Due to Nietzsche's ideals being synonymous with Zionism, Nietzsche now became more relevant in Nordau's life.[4] As his life progressed, he became closer to Nietzsche's ideology and was even influenced by Nietzsche's essay on history, as were many Zionists.[4]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Aschheim, Steven E. (1992). The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany 1890-1990. University of California Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-520-07805-5.

- ^ Katz, Steven T. (1992). Historicism, the Holocaust, and Zionism. NYU Press. pp. 289–299.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Golomb, Jacob (2004). ""Thus Spoke Herzl": Nietzsche's Presence in Theodor Herzl's Life and Work". Nietzsche and Zion. Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press. pp. 23–45. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctv5qdjn7.6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Golomb, Jacob (2004). Nietzsche and Zion. Cornell University Press. pp. 46–64, 159–188.

- ^ "Theodor Herzl". The Herzl Institute. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Mendes-Flohr, Paul (2001). "Zarathustra as a Prophet of Jewish Renewal: Nietzsche and the Young Martin Buber". Revista Portugesa de Filosofia. 57: 103–111 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Aschheim, Steven E. (1992). The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany 1890-1990. University of California Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-520-07805-5.

- ^ Aschheim, Steven E. (1992). The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany 1890-1990. University of California Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-520-07805-5.

- ^ Aschheim, Steven E. (1992). The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany 1890-1990. University of California Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-520-07805-5.

- ^ a b Reinharz, Jehuda (1983). "The Shaping of a Zionist Leader Before the First World War". Journal of Contemporary History. 18: 205–231 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Zionism and Israel - Max Nordau Biography". www.zionism-israel.com. Retrieved 2018-11-18.