Nick Cave

Nick Cave | |

|---|---|

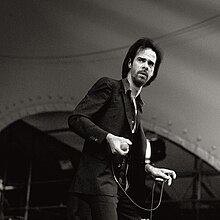

Cave performing live in 2021 | |

| Born | Nicholas Edward Cave 22 September 1957 Warracknabeal, Victoria, Australia |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1973–present |

| Spouses |

|

| Partner | Anita Lane (1977–1983) |

| Children | 4 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Discography | Nick Cave discography |

| Labels | |

| Member of | Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | nickcave |

Nicholas Edward Cave AO FRSL (born 22 September 1957[2]) is an Australian musician, writer and actor. Known for his baritone voice and for fronting the rock band Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Cave's music is characterised by emotional intensity, a wide variety of influences and lyrical obsessions with death, religion, love and violence.[3]

Born and raised in rural Victoria, Cave studied art in Melbourne before fronting the Birthday Party, one of the city's leading post-punk bands, in the late 1970s. In 1980 they moved to London, England. Disillusioned by their stay there, they evolved towards a darker and more challenging sound that helped inspire gothic rock, and acquired a reputation as "the most violent live band in the world".[4] Cave became recognised for his confrontational performances, his shock of black hair and pale, emaciated look. The band broke up soon after relocating to West Berlin in 1982. The following year, Cave formed Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, later described as one of rock's "most redoubtable, enduring" bands.[5] Much of their early material is set in a mythic American Deep South, drawing on spirituals and Delta blues, while Cave's preoccupation with Old Testament notions of good versus evil culminated in what has been called his signature song, "The Mercy Seat" (1988), and in his debut novel, And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989). In 1988, he appeared in Ghosts… of the Civil Dead, an Australian prison film which he both co-wrote and scored.

The 1990s saw Cave move between São Paulo and England, and find inspiration in the New Testament. He went on to achieve mainstream success with quieter, piano-driven ballads, notably the Kylie Minogue duet "Where the Wild Roses Grow" (1996), and "Into My Arms" (1997). Turning increasingly to film in the 2000s, Cave wrote the Australian Western The Proposition (2005), also composing its soundtrack with frequent collaborator Warren Ellis. The pair's film score credits include The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), The Road (2009) and Hell or High Water (2016). Their garage rock side project Grinderman has released two studio albums since 2006. In 2009, he released his second novel, The Death of Bunny Munro, and starred in the semi-fictional "day in the life" film 20,000 Days on Earth (2014). His more recent musical work features ambient and electronic elements, as well as increasingly abstract lyrics, informed in part by grief over his son Arthur's 2015 death, which is explored in the documentary One More Time with Feeling (2016) and the Bad Seeds' seventeenth and latest studio album, Ghosteen (2019).

Since 2018, Cave has maintained The Red Hand Files, a newsletter he uses to respond to questions from fans. He has collaborated with the likes of Johnny Cash, Shane MacGowan and ex-partner PJ Harvey, and his songs have been covered by a wide range of artists, including Cash ("The Mercy Seat"), Metallica ("Loverman") and Snoop Dogg ("Red Right Hand"). He was inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame in 2007,[6] and named an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2017.

Early life and education[edit]

Cave was born on 22 September 1957 in Warracknabeal, a country town in the Australian state of Victoria, to Dawn Cave (née Treadwell) and Colin Frank Cave.[7][8] As a child, he lived in Warracknabeal and then Wangaratta in rural Victoria. His father taught English and mathematics at the local technical school; his mother was a librarian at the high school that Cave attended.[9] From an early age, Cave's father read him literary classics, such as Crime and Punishment and Lolita,[10] and also organised the first symposium on the Australian bushranger and outlaw Ned Kelly,[11] with whom Cave was enamoured as a child.[12] Through his older brother, Cave became a fan of progressive rock bands such as King Crimson, Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull,[13] while a childhood girlfriend introduced him to Leonard Cohen, who he later described as "the greatest songwriter of them all".[14]

When Cave was nine he joined the choir of Wangaratta's Holy Trinity Cathedral.[7] At 13 he was expelled from Wangaratta High School,[10] and sent by his parents to Melbourne to become a boarder and later day student at Caulfield Grammar School.[9] His family moved to Melbourne the following year, settling in the suburb of Murrumbeena. After his secondary schooling, Cave studied painting at the Caulfield Institute of Technology in 1976, but dropped out the following year to pursue music.[15] He also began using heroin around the time that he left art school.[16]

Cave attended his first music concert at Melbourne's Festival Hall. The bill consisted of Manfred Mann, Deep Purple and Free. Cave recalled: "I remember sitting there and feeling physically the sound going through me."[15] In early 1977, he saw Australian punk rock groups Radio Birdman and the Saints live for the first time. Cave was particularly inspired by the show of the latter band, saying that he left the venue "a different person";[17] a photograph by Rennie Ellis shows Cave in the front row, appearing awestruck by the Saints' frontman Chris Bailey.[18]

Cave was 21 when his father was killed in a car collision; his mother told him of his father's death while she was bailing him out of a St Kilda police station where he was being held on a charge of burglary. He would later recall that his father "died at a point in my life when I was most confused" and that "the loss of my father created in my life a vacuum, a space in which my words began to float and collect and find their purpose".[10]

Music career[edit]

Early years and the Birthday Party (1973–1983)[edit]

In 1973, Cave met Mick Harvey (guitar), Phill Calvert (drums), John Cochivera (guitar), Brett Purcell (bass), and Chris Coyne (saxophone); fellow students at Caulfield Grammar. They founded a band with Cave as singer. Their repertoire consisted of rudimentary cover versions of songs by Lou Reed, David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Roxy Music and Alex Harvey, among others. Later, the line-up slimmed down to four members including Cave's friend Tracy Pew on bass. In 1977, after leaving school, they adopted the name The Boys Next Door and began playing predominantly original material. Guitarist and songwriter Rowland S. Howard joined the band in 1978.

They were a leader of Melbourne's post-punk scene in the late 1970s, playing hundreds of live shows in Australia before changing their name to the Birthday Party in 1980 and moving to London, then West Berlin. Cave's Australian girlfriend and muse Anita Lane accompanied them to London. The band were notorious for their provocative live performances which featured Cave shrieking, bellowing and throwing himself about the stage, backed up by harsh pounding rock music laced with guitar feedback. Cave used Old Testament imagery with lyrics about sin, debauchery and damnation.[19]

Cave's droll sense of humour and penchant for parody is evident in many of the band's songs, including "Nick the Stripper" and "King Ink". "Release the Bats", one of the band's most famous songs, was intended as an over-the-top "piss-take" on gothic rock, and a "direct attack" on the "stock gothic associations that less informed critics were wont to make". Ironically, it became highly influential on the genre, giving rise to a new generation of bands.[20] Cave attended a gig of the Pop Group and was so inspired by their performance, he stated that: "...It was one of those moments we just feel the cogs of your mind shift and your life is going to be irreversibly changed forever."[21]

After establishing a cult following in Europe and Australia, the Birthday Party disbanded in 1983.

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (1984–present)[edit]

The band with Cave as their leader and frontman has released seventeen studio albums. Pitchfork Media calls the group one of rock's "most enduring, redoubtable" bands, with an accomplished discography.[22] Though their sound tends to change considerably from one album to another, the one constant of the band is an unpolished blending of disparate genres, and song structures which provide a vehicle for Cave's virtuosic, frequently histrionic theatrics. Critics Stephen Thomas Erlewine and Steve Huey wrote: "With the Bad Seeds, Cave continued to explore his obsessions with religion, death, love, America, and violence with a bizarre, sometimes self-consciously eclectic hybrid of blues, gospel, rock, and arty post-punk."[3]

Reviewing 2008's Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! album, NME used the phrase "gothic psycho-sexual apocalypse" to describe the "menace" present in the lyrics of the title track.[23] Their most recent work, Ghosteen, was released in October 2019.[24]

In mid-August 2013, Cave was a 'First Longlist' finalist for the 9th Coopers Australian Music Prize, alongside artists such as Kevin Mitchell and the Drones. This music prize is worth A$30,000.[25] The prize ultimately went to Big Scary.[26]

In a September 2013 interview, Cave explained that he returned to using a typewriter for songwriting after his experience with the Nocturama album, as he "could walk in on a bad day and hit 'delete' and that was the end of it". Cave believes that he lost valuable work due to a "bad day".[15]

Grinderman (2006–present)[edit]

In 2006, Cave formed Grinderman with himself on vocals, guitar, organ and piano, Warren Ellis (tenor guitar, electric mandolin, violin, viola, guitar, backing vocals), Martyn P. Casey (bass, guitar, backing vocals) and Jim Sclavunos (drums, percussion, backing vocals). The alternative rock outfit was formed as "a way to escape the weight of The Bad Seeds".[27] The band's name was inspired by a Memphis Slim song, "Grinder Man Blues", which Cave is noted to have started singing during one of the band's early rehearsal sessions. The band's debut studio album, Grinderman, was released in 2007 to positive reviews and the band's second and final studio album, Grinderman 2, was released in 2010 to a similar reception.[citation needed]

Grinderman's first public performance was at All Tomorrow's Parties in April 2007 where Bobby Gillespie from Primal Scream accompanied Grinderman on backing vocals and percussion.[citation needed]

In December 2011, after performing at the Meredith Music Festival, Cave announced that Grinderman was over.[28] Two years later, Grinderman performed both weekends at the 2013 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, as did Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds.[29]

Music in film and television drama[edit]

Cave's musical work was featured in a scene of the 1986 film, Dogs in Space by Richard Lowenstein.[30] Cave performed parts of the Boys Next Door song "Shivers" twice during the film, once on video and once live.

Another early fan of Cave's was German director Wim Wenders, who lists Cave, along with Lou Reed and Portishead, as among his favourites.[31] Cave and the Bad Seeds appear in the film 1987 film Wings of Desire performing "The Carny" and "From Her to Eternity".[32] Two original songs were included in Wenders' 1993 sequel Faraway, So Close!, including the title track. The soundtrack for Wenders' 1991 film Until the End of the World features, another Cave original, "(I'll Love You) Till the End of the World". Cave and the Bad Seeds later recorded a live in-studio cover track for Wenders' 2003 documentary The Soul of a Man, and his 2008 film Palermo Shooting features two original songs from Cave's side project Grinderman.[33]

Cave's songs have also appeared in a number of Hollywood blockbusters – "There is a Light" appears on the 1995 soundtrack for Batman Forever, and "Red Right Hand" appeared in a number of films including The X-Files, Dumb & Dumber; Scream, its sequels Scream 2 and 3, and Hellboy (performed by Pete Yorn). In Scream 3, the song was given a reworking with Cave writing new lyrics and adding an orchestra to the arrangement of the track. "People Ain't No Good" was featured in the animated movie Shrek 2 and the song "O Children" was featured in the 2010 movie Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1.

In 2000, Andrew Dominik used "Release the Bats" in his film Chopper. Numerous other movies use Cave's songs including Box of Moonlight (1996), Mr In-Between (2001), Romance & Cigarettes (2005), Cirque du Freak: The Vampire's Assistant (2009), The Freshman, Gas Food Lodging, Kevin & Perry Go Large, About Time

His works also appear in a number of major TV programmes among them Trauma, The L Word, Traveler, The Unit, I Love the '70s, Outpatient, The Others, Nip/Tuck, and Californication. Most recently his work has appeared in the Netflix series After Life, BBC series Peaky Blinders and the Australian series Jack Irish. "Red Right Hand" is the theme song for Peaky Blinders and renditions of the track can be heard throughout the series, including covers by artists such as Arctic Monkeys, PJ Harvey, Laura Marling, Jarvis Cocker and Iggy Pop, Patti Smith and Anna Calvi. In a Vice interview, Peaky Blinders star Cillian Murphy mentioned that Cave personally approved the use of the song for the series after watching a pre-screening of the show.[34]

Collaborations[edit]

During the 1982 recording sessions for the Birthday Party's Junkyard LP, Cave, together with band-mates Harvey and Howard, joined members of the Go-Betweens to form Tuff Monks. The short-lived band released one single, "After the Fireworks", and played live only once. Later that year, Cave contributed to the Honeymoon in Red concept album. Intended as a collaboration between the Birthday Party and Lydia Lunch, the album was not released until 1987, by which time Lunch had fallen out with Cave, who she credits on the release as "Anonymous", "Her Dead Twin" and "A Drunk Cowboy Junkie".[35]

During the Birthday Party's Berlin period, Cave collaborated with local post-punk group Die Haut on their album Burnin' the Ice, released in 1983. In the immediate aftermath of the Birthday Party's breakup, Cave performed several shows in the United States as part of The Immaculate Consumptive, a short-lived "super-group" with Lunch, Marc Almond and Clint Ruin.[35] Cave sang on an Annie Hogan song called "Vixo" which was recorded in October 1983: the track was released in 1985 on the 12" inch vinyl "Annie Hogan – Plays Kickabye".[36]

A lifelong fan of Johnny Cash, Cave covered his song "The Singer", originally "The Folk Singer", for the 1986 album Kicking Against the Pricks, which Cash seemingly repaid by covering "The Mercy Seat" on American III: Solitary Man (2000). Cave was then invited to contribute to the liner notes of the retrospective The Essential Johnny Cash CD, released to coincide with Cash's 70th birthday. Subsequently, Cave recorded a duet with Cash, a version of Hank Williams' "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry", for what would be Cash's final album, American IV: The Man Comes Around (2002). Another duet between the two artists, the American folk song "Cindy", was released posthumously on Unearthed, a boxset of outtakes. Cave's song "Let the Bells Ring", released on the 2004 album Abattoir Blues / The Lyre of Orpheus, is a posthumous tribute to Cash.

Cave played with Shane MacGowan on cover versions of Bob Dylan's "Death is Not the End" and Louis Armstrong's "What a Wonderful World". Cave also performed "What a Wonderful World" live with the Flaming Lips. Cave recorded a cover version of the Pogues song "Rainy Night in Soho", written by MacGowan. MacGowan also sings a version of "Lucy", released on B-Sides and Rarities. On 3 May 2008, during the Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! tour, MacGowan joined Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds on stage to perform "Lucy" at Dublin Castle in Ireland. Pulp's single "Bad Cover Version" includes on its B-side a cover version by Cave of that band's song "Disco 2000". On the Deluxe Edition of Pulp's Different Class another take of this cover can be found.

In 2004, Cave gave a hand to Marianne Faithfull on the album, Before the Poison. He co-wrote and produced three songs ("Crazy Love", "There is a Ghost" and "Desperanto"), and the Bad Seeds are featured on all of them. He is also featured on "The Crane Wife" (originally by the Decemberists), on Faithfull's 2008 album, Easy Come, Easy Go.

Cave provided guest vocals on the title track of Current 93's 1996 album All the Pretty Little Horses, as well as the closer "Patripassian". For his 1996 album Murder Ballads, Cave recorded "Where the Wild Roses Grow" with Kylie Minogue, and "Henry Lee" with PJ Harvey.

Cave also took part in the "X-Files" compilation CD with some other artists, where he reads parts from the Bible combined with own texts, like "Time Jesum ...", he outed himself as a fan of the series some years ago, but since he does not watch much TV, it was one of the only things he watched. He collaborated on the 2003 single "Bring It On", with Chris Bailey, formerly of the Australian punk group, The Saints. Cave contributed vocals to the song "Sweet Rosyanne", on the 2006 album Catch That Train! from Dan Zanes & Friends, a children's music group.

In 2010, Nick Cave began a series of duets with Debbie Harry for The Jeffrey Lee Pierce Sessions Project.[37][38][39]

In 2011, Cave recorded a cover of the Zombies' "She's Not There" with Neko Case, which was used at the end of the first episode of the fourth season of True Blood.

In 2014, Cave wrote the libretto for the opera Shell Shock (opera) by Nicholas Lens.[40][41][42] The opera premiered at the Royal Opera House La Monnaie in Brussels on 24 October 2014[43] and was also set up at the international Weekend of War and Peace, Paris[44] on 10 and 11 November 2018 performed by L' Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France at Cité de la Musique (Philharmonie de Paris)[45] with live television broadcasting on Arte[46][47][better source needed] and France Musique.[48]

In 2020, Cave wrote the libretto for L.I.T.A.N.I.E.S, a trance-minimal chamber opera by Nicholas Lens. A recording produced by both writers was released by Deutsche Grammophon.[49][50][51][52]

Film scores and theatre music[edit]

"When Cave makes a brief appearance in the film's waning minutes—playing a grungy troubadour, of course, strolling the length of a bar as he growls the oft-sung folk tribute to Jesse James—you almost get the feeling that in some ways it's been Cave, by way of his score, telling the story all along."

— Pitchfork reviewing the soundtrack for The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)[53]

Cave creates original film scores with fellow Bad Seeds band member Warren Ellis—they first teamed up in 2005 to work on Hillcoat's bushranger film The Proposition, for which Cave also wrote the screenplay.[54]

In 2006, Cave and Ellis composed the music for Andrew Dominik's adaptation of Ron Hansen's The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.[55] By the time Dominik's film was released, Hillcoat was preparing his next project, The Road, an adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's novel about a father and son struggling to survive in a post-apocalyptic world. Cave and Ellis wrote and recorded the score for the film, which was released in 2009.[56] In 2011, Cave and Ellis reunited with Hillcoat to score his latest picture, Lawless. Cave also authored this screenplay based on Matt Bondurant's novel The Wettest County in the World. Set in Depression-era Franklin County, Virginia, the film was released in 2012.[57]

In 2016, Cave and Ellis scored the neo-Western film Hell or High Water, directed by David Mackenzie. The following year, they scored Taylor Sheridan's neo-Western Wind River, as well as Australian director David Michôd's War Machine.

Cave and Ellis have also scored a number of documentary films, including The English Surgeon (2007), West of Memphis (2012), Prophet's Prey (2015) and The Velvet Queen (2021). Cave and Ellis created music for the Vesturport productions Woyzeck, The Metamorphosis and Faust.[58]

Writing[edit]

Cave released his first book, King Ink, in 1988. It is a collection of lyrics and plays, including collaborations with Lydia Lunch. This was followed up with King Ink II in 1997, containing lyrics, poems, and the transcript of a radio essay he wrote for the BBC in July 1996, "The Flesh Made Word", discussing in biographical format his relationship with Christianity.

While he was based in West Berlin, Cave started working on what was to become his debut novel, And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989). Significant crossover is evident between the themes in the book and the lyrics Cave wrote in the late stages of the Birthday Party and the early stage of his solo career. "Swampland", from Mutiny, in particular, uses the same linguistic stylings ('mah' for 'my', for instance) and some of the same themes (the narrator being haunted by the memory of a girl called Lucy, being hunted like an animal, approaching death and execution).

In 1993, Cave and Lydia Lunch published an adult comic book they wrote together, with illustrations by Mike Matthews, titled AS-FIX-E-8.[59]

On 21 January 2008, a special edition of Cave's novel And the Ass Saw the Angel was released.[60] Cave's second novel The Death of Bunny Munro was published on 8 September 2009 by HarperCollins books.[61][62] Telling the story of a sex-addicted salesman, it was also released as a binaural audio-book produced by British Artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard and an iPhone app.[63] The book originally started as a screenplay Cave was going to write for John Hillcoat.[64]

In 2015 he released the book The Sick Bag Song, followed in 2022 by Faith, Hope, and Carnage, collected from a series of phone conversations conducted between Cave and Sean O'Hagan during the COVID-19 pandemic.[65]

Contributions[edit]

Aside from their soundtracks, Cave also wrote the screenplays for John Hillcoat's The Proposition (2005) and Lawless (2012).

Cave wrote the foreword to a Canongate publication of the Gospel According to Mark, published in the UK in 1998. The American edition of the same book (published by Grove Press) contains a foreword by the noted American writer Barry Hannah.

Cave is a contributor to a 2009 rock biography of the Triffids, Vagabond Holes: David McComb and the Triffids, edited by Australian academics Niall Lucy and Chris Coughran.[66]

Acting[edit]

Cave's first film appearance was in Wim Wenders' 1987 film Wings of Desire, in which he and the Bad Seeds are shown performing at a concert in Berlin.

Cave has made occasional appearances as an actor. He appears alongside Blixa Bargeld in the 1988 Peter Sempel film Dandy, playing dice, singing and speaking from his Berlin apartment. He is most prominently featured in the 1989 film Ghosts... of the Civil Dead, written and directed by John Hillcoat, and in the 1991 film Johnny Suede with Brad Pitt.

Cave appeared in the 2005 homage to Leonard Cohen, Leonard Cohen: I'm Your Man, in which he performed "I'm Your Man" solo, and "Suzanne" with Julie Christensen and Perla Batalla. He also appeared in the 2007 film adaptation of Ron Hansen's novel The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, where he sings "The Ballad of Jesse James".[67] Cave and Warren Ellis are credited for the film's soundtrack.[68] Nick Cave and his son Luke performed one of the songs on the soundtrack together. Luke played the triangle.[69]

His interest in the work of Edward Gorey led to his participation in the BBC Radio 3 programme Guest + Host = Ghost, featuring Peter Blegvad and the radiophonic sound of the Langham Research Centre.[70]

Cave has also lent his voice in narrating the animated film The Cat Piano. It was directed by Eddie White and Ari Gibson (of the People's Republic of Animation), produced by Jessica Brentnall and features music by Benjamin Speed.[71]

Screenwriting[edit]

Cave wrote the screenplay for The Proposition, a film about bushrangers in the Australian outback during the late 19th century. Directed by John Hillcoat and filmed in Queensland in 2004, it premiered in October 2005 and was later released worldwide to critical acclaim.[72] Cave explained his personal background in relation to writing the film's screenplay in a 2013 interview:

I had written long-form before but it is pure story-telling in script writing and that goes back as far as I can remember for me, not just with my father but with myself. I slept in the same bedroom as my sister for many years, until it became indecent to do so and I would tell her stories every night—that is how she would get to sleep. She would say "tell me a story" so I would tell her a story. So that ability, I very much had that from the start and I used to enjoy that at school so actually to write a script—it suddenly felt like I was just making up a big story.[15]

The film critic for British newspaper The Independent called The Proposition "peerless", "a star-studded and uncompromisingly violent outlaw film".[73] The generally ambient soundtrack was recorded by Cave and Warren Ellis.

At the request of his friend Russell Crowe, Cave wrote a script for a proposed sequel to Gladiator which was rejected by the studio.[74]

An announcement in February 2010 stated that Andy Serkis and Cave would collaborate on a motion-capture movie of the Brecht and Weill musical The Threepenny Opera. As of September 2019, the project has not been realised.[75]

Cave wrote a screenplay titled The Wettest County in the World,[76] which was used for the 2012 film Lawless, directed again by John Hillcoat, starring Tom Hardy and Shia LaBeouf.[77]

Blogging[edit]

Cave currently maintains a personal blog and an online correspondence page with his fans called The Red Hand Files which is seen as a continuation of In Conversation, a series of live personal talks Cave had held in which the audience were free to ask questions. On the page, Cave discusses various issues ranging from art, religion, current affairs and music, as well as using it as a free platform in which fans are encouraged to ask personal questions on any topic of their choosing.[78][79] Cave's intimate approach to the Question & Answer format on The Red Hand Files was praised by The Guardian as "a shelter from the online storm free of discord and conspiracies, and in harmony with the internet vision of Tim Berners-Lee."[79]

In January 2023, after being sent a song written by ChatGPT "in the style of Nick Cave",[80] he responded on The Red Hand Files (and was later quoted in The Guardian) saying that act of song writing "is not mimicry, or replication, or pastiche, it is the opposite, it is an act of self-murder that destroys all one has strived to produce in the past." He went on to say "It's a blood and guts business [that] requires my humanness", concluding that "this song is bullshit, a grotesque mockery of what it is to be human, and, well, I don't much like it."[80][81]

Legacy and influence[edit]

In 2010, Cave was ranked the 19th greatest living lyricist in NME.[82] Flea called him the greatest living songwriter in 2011.[83] Rob O'Connor of Yahoo! Music listed him as the 23rd best lyricist in rock history.[84] The Art of Nick Cave: New Critical Essays was edited by academic John H. Baker and published in 2013. In an essay on the album The Boatman's Call, Peter Billingham praised Cave's love songs as characterised by a "deep, poetic, melancholic introspection".[85] Carl Lavery, another academic featured in the collection, argued that there was a "burgeoning field of Cave studies".[86] Dan Rose argued that Cave "is a master of the disturbing narrative and chronicler of the extreme, though he is also certainly capable of a subtle romantic vision. He does much to the listener who enters his world."[87]

Songs written about Cave include "Just a King in Mirrors" (1983) by The Go-Betweens,[88] "Sick Man" (1984) by Foetus,[89] and "Bill Bailey" (1987) by The Gun Club.[90]

A number of prominent noise rock vocalists have cited Cave's Birthday Party-era work as their primary influence, including The U-Men's John Bigley,[91] and David Yow, frontman of Scratch Acid and The Jesus Lizard. Yow stated: "For a long time, particularly with Scratch Acid, I was so taken with the Birthday Party that I would deny it",[92] and that "it sounded like I was trying to be Birthday Party Nick Cave—which I was."[93] Often compared to Cave in his vocal delivery, Alexis Marshall of Daughters said that he admires the personality and energy within Cave's voice, and that his early albums "exposed [him] to lyrical content as literature".[94]

Personal life[edit]

Cave left Australia in 1980. After stints living in London, Berlin, and São Paulo, he moved to Brighton, England, in the early 2000s.[citation needed]

The 2014 film 20,000 Days on Earth, about Cave's life, is set around Brighton.[95] In 2017, Cave reportedly told GQ magazine that he and his family were considering moving from Brighton to Los Angeles as, after the death of his 15-year-old son, Arthur, they "just find it too difficult to live here."[96]

In November 2021, whilst answering a question on The Red Hand Files which was referencing the song "Heart That Kills" (from the album B-Sides & Rarities Part II) Cave stated, "The words of the song go someway toward articulating why Susie and I moved from Brighton to L.A. Brighton had just become too sad. We did, however, return once we realised that, regardless of where we lived, we just took our sadness with us. These days, though, we spend much of our time in London, in a tiny, secret, pink house, where we are mostly happy."[97]

Cave was a guest at the Coronation of Charles III and Camilla in 2023.[98][99]

In June 2023, in The Archbishop Interview with Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, on BBC Radio 4, Cave spoke about being a heroin addict for 20 years. Although his life during that time was admittedly "a terrible shambles", his second decade of addiction was much more stable and characterised by taking regularly heroin in the morning and in the evening and being able to work writing during the day.[100]

Partners and children[edit]

Cave dated Anita Lane from the late 1970s to mid-1980s.[101] Cave and Lane recorded together on a few occasions. Their most notable collaborations include Lane's "cameo" verse on Cave's Bob Dylan cover "Death Is Not The End" from the album Murder Ballads, and a cover of the Serge Gainsbourg/Jane Birkin song "Je t'aime... moi non plus/ I love you ... me neither".[102] Lane co-wrote the lyrics to the title track for Cave's 1984 LP, From Her to Eternity, as well as the lyrics of the song "Stranger Than Kindness" from Your Funeral, My Trial.[103]

Cave then moved to São Paulo, Brazil, in 1990, where he met and married his first wife, Brazilian journalist Viviane Carneiro. She gave birth to their son Luke in 1991. Cave and Carneiro were married for six years and divorced in 1996.[104]

Cave's son Jethro was also born in 1991, just ten days before Luke, and grew up with his mother, Beau Lazenby, in Melbourne, Australia. Cave and Jethro did not meet one another until Jethro was about seven or eight.[105][106] Jethro Lazenby, also known as Jethro Cave, died in May 2022, aged 31.[107]

Cave briefly dated PJ Harvey during the mid-1990s, with whom he recorded the duet "Henry Lee". Their breakup influenced his 1997 album The Boatman's Call.[108]

In 1997, Cave met British model Susie Bick; they married in 1999. Their twin sons, Arthur and Earl, were born in London in 2000 and raised in Brighton.[109][110][111][112] Bick is the model on the cover of Cave's album Push the Sky Away.[113]

When he was 15 years old, Cave's son Arthur fell from a cliff at Ovingdean, near Brighton, and died from his injuries on 14 July 2015.[114][115][116] An inquest found that Arthur had taken LSD before the fall and the coroner ruled his death was an accident.[117] The effect of Arthur's death on Cave and his family was explored in the 2016 documentary film One More Time with Feeling and the 2019 album Ghosteen.

Cave is the godfather to Michael Hutchence's daughter Heavenly Hiraani Tiger Lily.[118] Cave performed "Into My Arms" at the televised funeral of Hutchence, but insisted that the cameras cease rolling during his performance.

Religion[edit]

Cave is an avid reader of the Christian Bible. In his recorded lectures on music and songwriting, Cave said that any true love song is a song for God, and ascribed the mellowing of his music to a shift in focus from the Old Testament to the New. When asked if he had interest in religions outside of Christianity, Cave quipped that he had a passing, sceptical interest but was a "hammer-and-nails kind of guy".[119] Despite this, Cave has also said he is critical of organised religion. When interviewed by Jarvis Cocker on 12 September 2010, for his BBC Radio 6 show Jarvis Cocker's Sunday Service, Cave said that "I believe in God in spite of religion, not because of it."[120]

Cave has always been open about his doubts. When asked in 2009 about whether he believed in a personal God, Cave's reply was "No".[121] The following year, he stated that "I'm not religious, and I'm not a Christian, but I do reserve the right to believe in the possibility of a god. It's kind of defending the indefensible, though; I'm critical of what religions are becoming, the more destructive they're becoming. But I think as an artist, particularly, it's a necessary part of what I do, that there is some divine element going on within my songs."[122]

Cave's religious doubts were once a source of discomfort to him, but he eventually concluded:

Although I've never been an atheist, there are periods when I struggled with the whole thing. As someone who uses words, you need to be able to justify your belief with language, I'd have arguments and the atheist always won because he'd go back to logic. Belief in God is illogical, it's absurd. There's no debate. I feel it intuitively, it comes from the heart, a magical place. But I still I fluctuate from day to day. Sometimes I feel very close to the notion of God, other times I don't. I used to see that as a failure. Now I see it as a strength, especially compared to the more fanatical notions of what God is. I think doubt is an essential part of belief.[123]

In 2019, Cave expressed his personal disagreement with both organised religion and atheism (in particular New Atheism) when questioned about his beliefs by a fan during a question and answer session on his Red Hand Files blog.[78] On the same blog, Cave confirmed he believed in God in June 2021.[124] By 2023, Cave characterised himself as not being a Christian but 'act[ing] like one'[125] and detailed in his 2022 book Faith, Hope, and Carnage that he regularly attends church.

In 2023, Cave wrote on his blog that he had sympathised with feminist author Ayaan Hirsi Ali's conversion from Islam to atheism after reading her book Infidel: My Life and had also considered himself an atheist. However, he described his growing interest in religion as a "slowly emergent state" and shaped by his upbringing in the Anglican church. He also clarified his view on Christianity was "non-political and fully personal and emotional" and described his religious beliefs as "bound up in the liturgy and the ritual and the poetry that swirls around the restless, tortured figure of Jesus, as presented within the sacred domain of the church itself. My religiousness is softly spoken, both sorrowful and joyful, broadening and deepening, imagined and true. It is worship and prayer. It is resilient yet doubting, and forever wrestles with the forces of rationality." He concluded by describing Hirsi Ali's 2023 article in UnHerd documenting her conversion to Christianity as a "laudable achievement" for its ability to "vex atheists and Christians alike."[126]

Politics[edit]

In November 2017, Cave resisted demands from musicians Brian Eno and Roger Waters to cancel two concerts in Tel Aviv. This was after both Eno and Waters published a letter asking Cave to avoid performing in Israel while "apartheid remains". Cave went on to describe the Boycotts, Divestment and Sanctions movement as "cowardly and shameful", and that calls to boycott the country are "partly the reason I am playing Israel – not as support for any particular political entity but as a principled stand against those who wish to bully, shame and silence musicians." He furthermore responded with an open letter to Eno to defend his position.[127][128][129]

In 2019, Cave wrote in defence of singer Morrissey after the latter expressed a series of controversial political statements during the release of his California Son album which led to some record stores refusing to stock it. Cave argued that Morrissey should have that right to freedom of speech to state his opinions while everyone should be able to "challenge them when and wherever possible, but allow his music to live on, bearing in mind we are all conflicted individuals." He also added it would be "dangerous" to censor Morrissey from expressing his beliefs.[130][78]

In response to a fan asking about his political beliefs, Cave expressed a disdain for "atheism, organised religion, radical bi-partisan politics and woke culture" on his Red Hand Files blog. He in particular singled out woke politics and culture for criticism, describing it as "finding energy in self-righteous belief and the suppression of contrary systems of thought" and "regardless of the virtuous intentions of many woke issues, it is its lack of humility and the paternalistic and doctrinal sureness of its claims that repel me."[78] In 2020, Cave also expressed opposition to cancel culture and misguided political correctness, describing both as "bad religion run amuck" and their "refusal to engage with uncomfortable ideas has an asphyxiating effect on the creative soul of a society."[131][132]

Cave has previously described himself as a supporter of freedom of speech in both his live In Conversation events and on his blog.[133] He has also argued against boycotting musicians for controversial actions or political opinions while giving a lecture at the Hay Festival in 2023, saying that audiences should not “eradicate the best of these people in order to punish the worst of them."[125]

In October 2022, Cave expressed support for the participants of the Mahsa Amini protests in Iran on his correspondence blog after being asked by a fan on the matter. He responded by stating "I am in awe of their courage and pray for their safety."[134]

In 2023, Cave disputed a characterisation of him as right-wing or conservative by The New Statesman magazine but added "I have these days what I would call a conservative temperament" and described himself as "conservative with a small c." He also clarified he was "not against progress" but "I just see things moving very rapidly and a whole lot of different things worry me a lot, like AI" and expressed criticism of the idea "that everything is systemically fucked". He also stated that his small-c conservative views had formed following the deaths of two of his sons, explaining "I think that I have an understanding of loss and what it is to lose something and how difficult it is to get that back" and argued that the demise of religion and spirituality "which may or may not be a good thing" had led to a "vacuum that we created that we don't really know what to do with".[125] He has also written in support of the rights of trans people, stating on his personal blog that "I love my trans fans fully [...] I also wish for them to receive every right inherent to them and for them to lead lives of dignity and freedom, devoid of violence and prejudice".[135]

Discography[edit]

- Studio albums

- Carnage (with Warren Ellis) (2021)

Publications[edit]

Publications by Cave[edit]

- King Ink (1988)

- And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989)

- King Ink II (1997)

- Complete Lyrics (2001)

- The Complete Lyrics: 1978–2006 (2007)

- The Death of Bunny Munro (2009)

- The Sick Bag Song (2015)

- Stranger Than Kindness, Nick Cave, Christina Beck, Darcey Steinke (2020)

- The Little Thing, Nick Cave (2021)[136]

- Faith, Hope and Carnage, Nick Cave, Sean O'Hagan (2022)[137]

Publications with contributions by Cave[edit]

- The Gospel According to Mark. Pocket Canons: Series 1. Edinburgh, Scotland: Canongate, 1998. ISBN 0-86241-796-1. UK edition. With an introduction by Cave to the Gospel of Mark.

Films[edit]

- 20,000 Days on Earth (2014) – co-written and directed by artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard; Cave also co-wrote the script with Forsyth and Pollard[95]

- One More Time with Feeling (2016) – directed by Andrew Dominik

- I Want Everything (2020) – short documentary by Paul Szynol about Larry Sloman, who records a tribute to Cave's son Arthur. Cave makes an appearance.[138]

- Idiot Prayer: Nick Cave Alone at Alexandra Palace (2020) – concert film

- This Much I Know to Be True (2022) – directed by Andrew Dominik

Exhibitions[edit]

- Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds European Tour 1992, Arts Centre Melbourne (then known as The Victorian Arts Centre), Melbourne, 4 December 1992 – 26 February 1993. A photographic exhibition by Peter Milne.[139]

- Nick Cave: The exhibition, Arts Centre Melbourne, Melbourne, November 2007.[140] Exhibition based on the Nick Cave collection at Australian Performing Arts Collection. Later toured nationally.[141][142][143]

- Stranger Than Kindness: The Nick Cave Exhibition, Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen, June 2020. The exhibition shows Cave's life and work and was co-curated by him.[144]

- We, Sara Hildén Art Museum, Tampere, Finland. September 2022 – January 2023. The exhibition shows 17 of Cave's hand-crafted ceramic figurines depicting Satan.[145]

Awards and honours[edit]

APRA Music Awards[edit]

The APRA Awards are presented annually from 1982 by the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA), "honouring composers and songwriters". They commenced in 1982.[146]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | "Do You Love Me?" | Song of the Year | Nominated | [147][148] |

| 1996 | Nick Cave | Songwriter of the Year | Won | |

| "Where the Wild Roses Grow" | Most Performed Australian Work | Nominated | ||

| Song of the Year | Nominated | |||

| 1998 | "Into My Arms" | Nominated | ||

| 2001 | "The Ship Song" | Top 30 Best Australian Songs | included | [149] |

| 2014 | "Jubilee Street" (with Warren Ellis) | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [150] |

| "We No Who U R" (with Warren Ellis) | Shortlisted | |||

| 2021 | "Ghosteen" (with Warren Ellis) | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [151] |

| 2022 | "Albuquerque" (with Warren Ellis) | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [152] |

ARIA Music Awards[edit]

The ARIA Music Awards is an annual awards ceremony that recognises excellence, innovation, and achievement across all genres of Australian music. They commenced in 1987.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Let Love In | Best Group | Nominated | |

| "Do You Love Me?" | Single of the Year | Nominated | ||

| 1996 | Murder Ballads | Album of the Year | Nominated | [153] |

| Best Alternative Release | Nominated | |||

| "Where the Wild Roses Grow" (with Kylie Minogue) | Song of the Year | Won | ||

| Single of the Year | Won | |||

| Best Pop Release | Won | |||

| 1997 | The Boatman's Call | Album of the Year | Nominated | [153] |

| Best Alternative Release | Nominated | |||

| "Into My Arms" | Song of the Year | Nominated | ||

| Single of the Year | Nominated | |||

| To Have and to Hold (Nick Cave with Blixa Bargeld & Mick Harvey) | Best Original Soundtrack / Cast / Show Recording | Won | ||

| 2001 | No More Shall We Part | Best Male Artist (Nick Cave) | Won | |

| 2003 | Nocturama | Best Male Artist (Nick Cave) | Nominated | [153] |

| Best Rock Album | Nominated | |||

| 2006 | The Proposition (Nick Cave with Warren Ellis ) | Best Original Soundtrack / Cast / Show Recording | Nominated | [154] |

| 2007 | Nick Cave | ARIA Hall of Fame | inducted | |

| 2008 | Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! | Album of the Year | Nominated | [153] |

| Best Male Artist (Cave) | Won | |||

| Best Rock Album | Nominated | |||

| 2013 | Push The Sky Away | Album of the Year | Nominated | [155] |

| Best Group | Nominated | |||

| Best Independent Release | Won | |||

| Best Adult Contemporary Album | Won | |||

| "Jubilee Street" (directed by John Hillcoat) | Best Video | Nominated | ||

| National Tour | Best Australian Live Act | Nominated | ||

| Lawless (with Warren Ellis) | Best Original Soundtrack / Cast / Show Recording | Nominated | ||

| 2014 | Live from KCRW | Best Adult Contemporary Album | Nominated | |

| 2015 | Nick Cave Australian Tour | Best Australian Live Act | Nominated | |

| 2017 | Skeleton Tree | Best Group | Nominated | |

| Best Adult Contemporary Album | Nominated | |||

| Australia & New Zealand Tour 2017 | Best Australian Live Act | Nominated | ||

| 2020 | Ghosteen | Best Independent Release | Nominated | |

| Best Adult Contemporary Album | Nominated | |||

| 2021 | Carnage (with Warren Ellis ) | Best Adult Contemporary Album | Nominated | [156] |

Australian Music Prize[edit]

The Australian Music Prize (the AMP) is an annual award of $30,000 given to an Australian band or solo artist in recognition of the merit of an album released during the year of award. It commenced in 2005.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[157] | Carnage (with Warren Ellis) | Australian Music Prize | Nominated |

EG Awards / Music Victoria Awards[edit]

The EG Awards (known as Music Victoria Awards since 2013) are an annual awards night celebrating Victorian music. They commenced in 2006.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| EG Awards of 2007[158] | Nick Cave & Grinderman – Forum Theatre | Best Tour | Won |

| EG Awards of 2008[159] | Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! | Best Album | Won |

| Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds | Best Band | Won |

Grammy Awards[edit]

The Grammy Awards are awarded annually by The Recording Academy to honor outstanding achievements in the music industry, and are considered the music industry's highest honor.[160]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | One More Time With Feeling | Best Music Film | Nominated | [161] |

| 2022 | Carnage | Best Recording Package | Nominated | [162] |

J Awards[edit]

The J Awards are an annual series of Australian music awards that were established by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's youth-focused radio station Triple J. They commenced in 2005.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | "Macca the Mutt" by Party Dozen featuring Nick Cave (directed by Tanya Babic & Jason Sukadana [Versus]) | Australian Video of the Year | Nominated | [163] |

Other awards[edit]

- Order of Australia: (2017) Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) "For distinguished service to the performing arts as a musician, songwriter, author and actor, nationally and internationally, and as a major contributor to Australian music culture and heritage."[164]

- 1990 Time Out Magazine: Book Of The Year (And the Ass Saw the Angel).

- 1996 MTV Europe Music Awards: Nick Cave formally requested that his nomination for "Best Male Artist" be withdrawn as he was not comfortable with the "competitive nature" of such awards.

- 2004 MOJO Awards: Best Album of 2004 (Abattoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheus).

- 2005 Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards: Best Musical Score (The Proposition).

- 2005 Inside Film Awards: Best Music (The Proposition).

- 2005 AFI Awards: Best Original Music Score with Warren Ellis (The Proposition).

- 2005 Q magazine: Q Classic Songwriter Award.

- 2006 Venice Film Festival: Gucci Award (for the script to The Proposition).

- 2008 Awarded an honorary degree as Doctor of Laws, by Monash University.[165]

- 2008 MOJO Awards: Best Album of 2008 (Dig, Lazarus Dig!!!).

- 2010 made an honorary Doctor of Laws, by University of Dundee.[166]

- 2011 MOJO Awards: Song of the Year for "Heathen Child" by Grinderman

- 2011 Straight to you – Triple j's tribute tour to Nick Cave for his work in Australian music for Ausmusic Month

- 2012 Doctor of Letters, an honorary degree from the University of Brighton.[167]

- 2014 International Istanbul Film Festival: International Competition: FIPRESCI Prize for "20,000 Days on Earth"

- 2014 Sundance Film Festival: World Cinema Documentary Directing Award & Editing Award for "20,000 Days on Earth"

- 2014 Festival de Cinéma de la Ville de Québec: Grand Prix competition – official feature for "20,000 Days on Earth"

- 2014 Athens International Film Festival: Music & Films Competition Golden Athena for "20,000 Days on Earth"

- 2014 The Ivor Novello Awards: Best Album award for song writing for "Push The Sky Away"

- 2014 British Independent Film Awards: The Douglas Hickox Award Best Debut Director for "20,000 Days on Earth"

- 2015 Cinema Eye Honors: Outstanding Original Music Score for "20,000 Days on Earth"

- 2022 Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature[168]

- National Live Music Awards of 2023: Best International Tour in Australia with Warren Ellis[169]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Wilkinson, Roy (31 December 2013). "Nick Cave's Top 10 Albums". Mojo. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

"Uncut summary 2003". Uncut. February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 February 2003. Retrieved 23 March 2017.The Godfather of Goth is back

- ^ "Nick Cave: Australian Musician and Author". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ a b Stephen Thomas Erlewine and Steve Huey, AllMusic, (((Nick Cave > Biography))). Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ Grice, Sarah (1 October 2014). "Film: 20,000 Days on Earth", Varsity. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Berman, Stuart (6 May 2009). "From Her to Eternity", Pitchfork. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "Nick Cave to enter ARIA Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on 5 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Curator's Notes". Western Australian Museum. 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "22 December 1949 – LIFE OF MELBOURNE Drama Prize". Trove.nla.gov.au. 22 December 1949. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ a b Hattenstone, Simon (23 February 2008). "Old Nick". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Maume, Chris. "Nick Cave: Devil's advocate", The Independent. Retrieved on 10 November 2008.

- ^ Cave, Colin (ed). Ned Kelly: Man and Myth. Wangaratta Adult Education Centre, 1962. ISBN 0-7269-1410-X, p. 10

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (24 February 2006). "Outback outlaws", The Guardian. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "From Pink Floyd to King Crimson: Nick Cave names his favourite guitarists of all time". Faroutmagazine.co.uk. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Padgett, Ray (2020). Various Artists' I'm Your Fan: The Songs of Leonard Cohen. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781501355073.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Sarah (11 September 2013). "10 things Nick Cave said at BIGSOUND 2013". Faster Louder. Faster Louder Pty Ltd. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Nick Cave, Style Icon". Enjoy-your-style.com. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ Dalziell, Tanya; Welberry, Karen (ed.). Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave. pp. 36–37.

- ^ Richards, Will (12 April 2022). "Nick Cave pays tribute to The Saints’ Chris Bailey, his “favourite singer”", Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (2005). Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–1984. London: Faber and Faber, 2005. pp. 429–431. ISBN 0-571-21569-6.

- ^ Welberry, Karren (ed.) (2016). Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave. Routledge. p. 87–88

- ^ "Nick Cave on The Pop Group (1999)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Stuart Berman, Pitchfork Media, "Album reviews: Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds: From Her to Eternity / The First Born is Dead / Kicking Against the Pricks / Your Funeral ... My Trial", 6 May 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ "Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds Dig!!! Lazarus Dig!!! (album review)". NME. 21 February 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Ruiz, Matthew. "Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds Release New Album Ghosteen: Listen". Pitchfork. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Hohnen, Mike (15 August 2013). "Nick Cave, The Drones, Bob Evans Make Longlist For $30,000 Coopers AMP". Music Feeds. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ ""Big Scary Win The 9th Coopers AMP For 'Not Art'"". MusicFeeds. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Cave, Nick (2010). "And Now It's Cave's Other Deranged Blues Band!". Uncut (September 2010): 55.

- ^ Marcus (11 December 2011). "Nick Cave announces that Grinderman are "over" – News | thevine.com.au". The Vine. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Fricke, David (11 April 2013). "Q&A: Nick Cave on His Coachella Sets and Denying Himself 'Sacred Moments'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Dogs in Space". Murdoch.edu.au. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Wenders unveils ode to rock'n'roll at Cannes". ABC News. 24 May 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Dave Tacon, "Wim Wenders", Senses of Cinema. Retrieved on 25 November 2008.

- ^ "The Blues: The Soul of a Man", PBS. Retrieved on 25 November 2008.

- ^ "Cillian Murphy: VICE Autobiographies", Vice. Retrieved on 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b Walker, Clinton (1984). The Next Thing. Kangaroo Press. ISBN 9780949924810. p. 14.

- ^ "Annie Hogan Plays "Kickabye" – liner notes for "Vixo" on the label Doublevision – DVR9 on 12" in 1985.

- ^ "The Jeffrey Lee Pierce Sessions Project – We Are Only Riders". Glitterhouse Records. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ "The Jeffrey Lee Pierce Sessions Project – The Journey is Long". Glitterhouse Records. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ "The Jeffrey Lee Pierce Sessions Project – Axels & Sockets". Glitterhouse Records. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Robert-Jan Bartunek (25 October 2014). "Shell Shock opera brings trauma of World War One to stage | Reuters". In.reuters.com. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "" Shell Shock " fait éprouver le traumatisme des tranchées". Le Monde.fr. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Nicholas Lens – Mute Song". Mutesong.com. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Program (Opera) | La Monnaie / De Munt". Lamonnaie.be. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Laspière, Victor Tribot (9 November 2018). "Shell Shock, un opéra de Nicholas Lens en hommage aux victimes de la Grande Guerre". France Musique (in French). Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Shell Shock, A Requiem of War". Philharmonie de Paris (in French). Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Shell Shock, A Requiem of War".

- ^ ARTE Concert (5 November 2018). "Shell Shock, A Requiem of War https://programm.ard.de/TV/arte/shell-shock--a-requiem-of-war/eid_28724971517354". Facebook. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Nicholas Lens – "Shell Shock" (Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France & Silesia Opera Choir)". France Musique. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "L.I.T.A.N.I.E.S Nicholas Lens & Nick Cave – Insights". www.deutschegrammophon.com. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Nick Cave teams up with composer Nicholas Lens for "lockdown opera" 'L.I.T.A.N.I.E.S'". NME. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Nick Cave and Nicholas Lens Collaborate on New Opera L.I.T.A.N.I.E.S". news.yahoo.com. 9 October 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Il 4 dicembre uscirà la "lockdown opera" di Nick Cave". Rolling Stone Italia (in Italian). 9 October 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Klein, Joshua (1 February 2008). "Nick Cave / Warren Ellis: The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford", Pitchfork. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Nick Cave and Warren Ellis The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford". Pitchfork.com. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Nick Cave and Warren Ellis The Road Review". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Sean O'Hagan. "Nick Cave: 'Lawless is not so much a true story as a true myth'". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Faust inspired by Goeth". Vesturport.com. 13 November 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "AS-FIX-E-8". Goodreads. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Nick Cave sees debut novel 'And The Ass Saw the Angel' re-released as collectors edition". Side-line.com. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Nick Cave announces release date for new novel – News". Nmr.com. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "The Death of Bunny Munro: A Novel By Nick Cave". Harpercollins.ca. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Breihan, Tom "Nick Cave's New Novel Bunny Munro Gets its Own iPhone App, Tour" Archived 9 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine September 2009.

- ^ Khanna, Vish "Conversations: Nick Cave" Archived 9 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine at Exclaim! October 2009.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney (28 March 2015). "Nick Cave: pass the sick bag". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Niall Lucy and Chris Coughran, eds. Vagabond Holes: David McComb and The Triffids (Fremantle: Fremantle Press, 2009).

- ^ Marshall, Lee (3 September 2007). "The Assassination Of Jesse James By The Coward Robert Ford". Screen Daily. Media Business Insight Limited. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Rose, Kara (6 December 2007). "Cave and Ellis For Jesse James Soundtrack". HARP. Guthrie, Inc. Archived from the original on 12 August 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "Luke Cave". IMDb.com. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "(none) – Between The Ears – Guest + Host = Ghost". BBC. 31 December 2005. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ "The Cat Piano". Catpianofilm.com. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Brett McCracken, Film Review of The Proposition Archived 18 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Relevant Magazine. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ^ Will Self, "The Proposition: Bringing the revisionist Western to the Australian outback," The Independent. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam, "10 Screenwriters to Watch: Nick Cave Archived 31 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine," Variety, 22 June 2006.

- ^ Goodridge, Mike (15 February 2010). "Serkis, Cave plan motion-capture Opera". Screen Daily. Media Business Insight Limited. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Dang, Simon (4 February 2011). "Nick Cave Confirms He'll Score John Hillcoat's 'The Wettest County'". indieWIRE. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Pelly, Jenn, "[1]," Pitchfork.com, 27 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Clarke, Patrick (15 October 2019). "Nick Cave says he's "repelled" by 'woke' culture's "self-righteous belief" and "lack of humility"". NME. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b Cunningham, Russell (27 November 2018). "Nick Cave is showing us a new, gentler way to use the internet". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b "'This song sucks': Nick Cave responds to ChatGPT song written in style of Nick Cave". the Guardian. 17 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Are AI-generated songs a 'grotesque mockery' of humanity or simply an opportunity to make a new kind of music? | Jeff Sparrow". the Guardian. 20 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ nme (15 April 2010). "The Greatest Lyricists In The World Today". NME. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ "Nick Cave – The Greatest Living Songwriter? | NME". NME Music News, Reviews, Videos, Galleries, Tickets and Blogs | NME.COM. 22 August 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ O'Connor, Rob (15 December 2014). "The 25 Best Rock Lyricists". Yahoo.com. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Baker 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Baker 2013, p. 29.

- ^ Baker 2013, p. 98.

- ^ Jelbert, Steve. "The Ten Rules of Rock 'n' Roll". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ Johnston, Ian (2020). Bad Seed: The Biography of Nick Cave. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 9780349144351.

- ^ Pierce, Jeffrey Lee (1998). Go Tell the Mountain: Jeffrey Lee Pierce, 2.13.61 Publications. ISBN 9781880985601.

- ^ Tow, Stephan (16 October 2011). "The Strangest Tribe: How a Group of Seattle Rock Bands Invented Grunge", Seattle Met. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Warmowski, Rob (10 November 2011). "David Yow of Scratch Acid talks to Rob Warmowski of Sirs", Chicago Reader. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Herzog, Kenny (27 June 2013). "The Lizard King: David Yow on Three Decades of Music and Mayhem", Spin. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Cartledge, Luke (13 December 2019). "Nine Songs: Daughters", The Line of Best Fit. 14 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Interview: A Day in the Life of Nick Cave". The Guardian. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ Heath, Chris (27 April 2017). "The Love and Terror of Nick Cave". GQ. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "Nick Cave – The Red Hand Files – Issue #171 – When did you write "Heart That Kills You"? It is a beautiful thing". The Red Hand Files. 2 November 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "The Coronation of His Majesty the King and Her Majesty The Queen Consort". Australian Government. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "The host of famous faces to witness the Coronation". The Daily Telegraph. 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ "The Archbishop Interviews". The Archbishop Interviews. Nick Cave. 25 June 2023. BBC. BBC Radio 4.

- ^ Hage, Erik. "Anita Lane | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "I Love You....Nor Do I – Nick Cave, Mick Harvey, Anita Lane | Song Info". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "Anita Lane | Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "Nick Cave Interviews". Nick-cave.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ "Models and rockers: Jethro Cave and Leah Weller – Life & Style – London Evening Standard". Standard.co.uk. 12 November 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ Byrne, Fiona (28 September 2008). "Cave boy joins cool kids club". Herald & Weekly Times. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Aubrey, Elizabeth (9 May 2022). "Nick Cave's son Jethro Lazenby has died, aged 31". NME. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Harmon, Steph (28 August 2019). "Nick Cave on PJ Harvey break-up: 'I was so surprised I almost dropped my syringe'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Baker, Lindsay (1 February 2003). "Feelings are a Bourgeois luxury". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Bilcic, Pero. "Nick Cave Online". Nick-cave.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Webb, Beth (10 June 2020). "Earl Cave: "I'd love to play Neil Young in a film"". NME. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Elgot, Jessica; Khomami, Nadia (15 July 2015). "Nick Cave's son dies after Brighton chalk cliffs fall". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ McLean, Craig (12 May 2013). "'On stage I'm just me having a bad day': Nick Cave on 40 years of music and mayhem – Profiles – People". The Independent. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Marcus, Stephanie (15 July 2015). "Nick Cave's Son Arthur Dead At 15 After Falling Off A Cliff". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Leo, Ben (15 July 2015). "Rock legend Nick Cave's son killed in cliff fall". The Argus. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Nick Cave's son Arthur took LSD before cliff fall, inquest told". BBC Online. 2015. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "Nick Cave's son Arthur took LSD before cliff fall, inquest told". BBC News. 10 November 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Bertacchini, Lauren (26 February 2013). "Nick Cave: Fan Factoids". Everguide. Lifelounge Pty Ltd. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Bartlett, Thomas (18 November 2004). "The Resurrection of Nick Cave". Salon. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Cocker, Jarvis (12 September 2010). "Jarvis Cocker's Sunday Service". BBC 6. BBC. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "Nick Cave on The Death of Bunny Munro". The Guardian. 11 September 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

Do I personally believe in a personal God? No.

- ^ Payne, John (29 November 2010). "Nick Cave's master plan". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Snow, Mat (21 January 2011). Nick Cave: Sinner Saint: The True Confessions, Thirty Years of Essential Interviews. Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965448-7.

- ^ "Nick Cave – The Red Hand Files – Issue #153". www.theredhandfiles.com. June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Knight, Lucy (28 May 2023). "Nick Cave speaks out against boycotting songs because of creators' actions". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "I would love to hear your thoughts on Ayaan Hirsi Ali's recent essay, "Why I am now a Christian." These two sentences in particular made me think of you (and the almost entirely diminished atheist in me): "I have also turned to Christianity because I ultimately found life without any spiritual solace unendurable—indeed very nearly self-destructive. Atheism failed to answer a simple question: What is the meaning and purpose of life?"". 23 November 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (11 December 2018). "Nick Cave Defends Israel Concert in Open Letter to Brian Eno". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (11 December 2018). "Nick Cave: cultural boycott of Israel is 'cowardly and shameful'". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Spiro, Amy (12 December 2018). "NICK CAVE: BOYCOTTING ISRAEL IS 'COWARDLY AND SHAMEFUL'". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Yoo, Noah (28 June 2019). "Nick Cave Questions Morrissey's Politics, Defends His Music and Free Speech in Open Letter". Pitchfork. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Nick Cave: 'cancel culture is bad religion run amuck'". The Guardian. 12 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Nick Cave – The Red Hand Files – Issue #109". www.theredhandfiles.com. August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ O'Connor, Roisin (22 July 2019). "Nick Cave writes letter to homophobic 'fan' during Q&A: 'It's not too late for you'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "ISSUE #206". www.theredhandfiles.com. October 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "ISSUE #249". www.theredhandfiles.com. August 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ Tolkien, Tom (9 November 2021). "The Little Thing by Nick Cave". The School Reading List. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Knight, Lucy (17 September 2021). "Nick Cave to publish book about the years after his son's death". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "See Nick Cave Praise Rock Writer 'Ratso' in Trailer for Short Film". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Poster, music, "Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds European Tour 1992", a photographic exhibition by Peter Milne". Arts Centre Melbourne. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Donovan, Patrick (10 November 2007). "Nick Cave makes a public exhibition of himself". The Age. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ "reCollections – Nick Cave: The exhibition". recollections.nma.gov.au. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ "Curator's Notes | Western Australian Museum". museum.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ "Nick Cave". Arts Centre Melbourne. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Sayej, Nadja (18 June 2020). "Nick Cave's Art Exhibition Is A Trip Down Memory Lane". Forbes.

- ^ Jhala, Kabir (20 September 2022). "Brad Pitt makes his debut as a sculptor in Finland exhibition". CNN. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ "APRA History". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) | Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society (AMCOS). Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "History | APRA Music Awards". www.apra-amcos.com.au. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "1996 Winners – APRA Music Awards". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) | Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society (AMCOS). Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Kruger, Debbie (2 May 2001). "The songs that resonate through the years" (PDF). Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Nick Cave, Boy & Bear Lead APRA 2014 Song of the Year Shortlist". Music Feeds. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "One of these songs will be the Peer-Voted APRA Song of the Year!". APRA AMCOS. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "2022 Peer-Voted APRA Song of the Year shortlist revealed!". APRA AMCOS. 3 February 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "ARIA Awards 2008: History: Winners by Artist search result for Nick Cave". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- ^ ARIA Award previous winners. "History Best Original Soundtrack, Cast or Show Album". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Greg Moskovitch (1 December 2013). "ARIA Award 2013 Winners – Live Updates". Music Feeds. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Kelly, Vivienne (20 October 2021). "ARIA Awards nominees revealed: Amy Shark & Genesis Owusu lead the charge". The Music Network. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ "Australian Music Prize reveals 'strong & diverse' shortlist". The Music Network. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Music talent honoured at the EG Awards". The Age. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Nick Cave: 'Live and' Loud'; Son Jethro accepts EG Awards". Nick Cave Fixes. 21 December 2008. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Grammy Awards". Grammy. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "Sia, Nick Cave, Lorde score Grammy nods". SBS News. 29 November 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ Gbogbo, Mawunyo (3 April 2022). "These Australians have been nominated for a Grammy Award, with the 2022 ceremony due to take place tomorrow". ABC News. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Here's all the J Awards 2022 nominees!". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Officer (AO) in the General Division of the Order of Australia" (PDF). Australia Day 2017 Honours List. Governor-General of Australia. 26 January 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Smith, Bridie (29 March 2008). "Dr Cave is a law unto himself". The Age. Melbourne, Australia.

- ^ "Nick Cave awarded honorary degree". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 26 June 2010.

- ^ "Top university honour for city musician". The Argus. Brighton. 3 January 2012. [permanent dead link]

- ^ Shaffi, Sarah; Knight, Lucy (12 July 2022). "Adjoa Andoh, Russell T Davies and Michaela Coel elected to Royal Society of Literature". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Genesis Owusu And Amyl & The Sniffers Win Big At The 2023 National Live Music Awards". The Music. 11 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Bad Seed: A Biography of Nick Cave, Ian Johnston (1997) ISBN 0-316-90833-9

- The Life and Music of Nick Cave: An Illustrated Biography, Maximilian Dax & Johannes Beck (1999) ISBN 3-931126-27-7

- Liner notes to the CDs Original Seeds: Songs that inspired Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Kim Beissel (1998 & 2004), Rubber Records

- Kicking Against the Pricks: An Armchair Guide to Nick Cave, Amy Hanson (2005), ISBN 1-900924-96-X

- Nick Cave Stories, Janine Barrand (2007) ISBN 978-0-9757406-9-9

- Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave, eds. Karen Welberry and Tanya Dalziell (2009) ISBN 0-7546-6395-7

- Nick Cave Sinner Saint: The True Confessions, ed. Mat Snow (2011) ISBN 978-0-85965-448-7

- Baker, John H., ed. (2013). The Art of Nick Cave: New Critical Essays. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1841506272.

- A Little History: Nick Cave & cohorts 1981–2013, Bleddyn Butcher (2014) ISBN 9781760110680

- Nick Cave: Mercy on Me (2017), a graphic biography by Reinhard Kleist

- Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds: An Art Book, Reinhard Kliest (2018), ISBN 9781910593523

- Boy on Fire: The Young Nick Cave, Mark Mordue (2020)

External links[edit]

- Nick Cave

- 1957 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Australian novelists

- 20th-century Australian male writers

- 21st-century Australian novelists

- 20th-century Australian male singers

- 21st-century Australian male singers

- Alternative rock singers

- APRA Award winners

- ARIA Award winners

- ARIA Hall of Fame inductees

- Australian alternative rock musicians

- Australian baritones

- Australian composers

- Australian emigrants to England

- Australian expatriates in England

- Australian expatriates in Germany

- Australian male composers

- Australian male novelists

- Australian multi-instrumentalists

- Australian punk rock musicians

- Australian rock guitarists

- Gothic rock musicians

- Australian male guitarists

- Australian male singer-songwriters

- Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds members

- Noise rock musicians

- Australian opera librettists

- People educated at Caulfield Grammar School

- People from Wangaratta

- Post-punk musicians

- Singers from Melbourne

- People from Warracknabeal

- Officers of the Order of Australia

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- The Birthday Party (band) members

- The Immaculate Consumptive members

- Australian memoirists

- 20th-century Australian singer-songwriters

- 21st-century Australian singer-songwriters