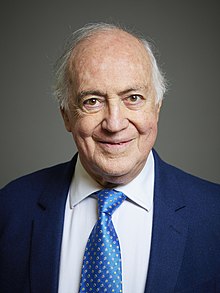

Michael Howard

The Lord Howard of Lympne | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Official portrait, 2023 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 November 2003 – 6 December 2005 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Tony Blair | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Michael Ancram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Iain Duncan Smith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | David Cameron | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Conservative Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 November 2003 – 6 December 2005[note 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Michael Ancram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Iain Duncan Smith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | David Cameron | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home Secretary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 27 May 1993 – 2 May 1997 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | John Major | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Kenneth Clarke | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jack Straw | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of State for the Environment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 11 April 1992 – 27 May 1993 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | John Major | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Michael Heseltine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | John Gummer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of State for Employment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 3 January 1990 – 11 April 1992 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher John Major | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Norman Fowler | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Gillian Shephard | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Michael Hecht 7 July 1941 Gorseinon, Swansea, Wales | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Conservative | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | Labour (1961) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2[citation needed] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Peterhouse, Cambridge Inns of Court School of Law | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael Howard, Baron Howard of Lympne CH PC KC (born Michael Hecht; 7 July 1941)[1] is a British politician who served as Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition from November 2003 to December 2005. He previously held cabinet positions in the governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major, including Secretary of State for Employment, Secretary of State for the Environment and Home Secretary.

Howard was born in Swansea to a Jewish family, his father from Romania and his mother from Wales. He studied at Peterhouse, Cambridge, following which he joined the Young Conservatives. In 1964, he was called to the Bar and became a Queen's Counsel in 1982. He first became a Member of Parliament at the 1983 general election, representing the constituency of Folkestone and Hythe. This quickly led to his promotion and Howard became Minister for Local Government in 1987. Under the premiership of John Major, he served as Secretary of State for Employment (1990–1992), Secretary of State for the Environment (1992–1993) and Home Secretary (1993–1997).

Following the Conservative Party's landslide defeat at the 1997 general election, he unsuccessfully contested the leadership, and subsequently held the posts of Shadow Foreign Secretary (1997–1999) and Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer (2001–2003). In November 2003, following the Conservative Party's vote of no confidence in Iain Duncan Smith, Howard was elected to the leadership unopposed.

At the 2005 general election, the Conservatives gained 33 new seats in Parliament, including five from the Liberal Democrats; but this still gave them only 198 seats to Labour's 355. Following the election, Howard resigned as Leader of the Conservative Party and was succeeded by David Cameron. Howard did not contest his seat of Folkestone and Hythe in the 2010 general election and entered the House of Lords as Baron Howard of Lympne. Prior to Brexit, he was supportive of the Eurosceptic pressure group Leave Means Leave.[2]

Early life[edit]

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

Howard was born Michael Hecht in Gorseinon, Swansea, son of Bernat Hecht (died 1966), who was born in Romania and came to Britain in 1939,[3] and Hilda (née Kershion), who had lived in Wales from the age of six months where her father was a draper in Llanelli. She was a cousin of the Landy family who had helped Bernat Hecht come to Britain.[4] Both of Howard's parents were from Jewish families.[5] Howard's grandmother was murdered at Auschwitz.[6]

Bernat Hecht was a synagogue cantor who worked for his wife's family drapery business, later establishing himself as a prominent local businessman, owning three shops in Llanelli.[7][8] When Howard was six, his parents became naturalised as British subjects and the family name was changed to Howard.[9][10]

Howard passed his eleven-plus exam in 1952 and then attended Llanelli Boys' Grammar School. He joined the Young Conservatives at age 15. He gained a place at Peterhouse, Cambridge, where he was President of the Cambridge Union in 1962.[1] After taking a 2:1 in the first part of the economics tripos, he switched to law and graduated with a 2:2 in 1962.[citation needed]

He was one of a cluster of Conservative students at Cambridge University around this time, sometimes referred to as the "Cambridge Mafia", many of whom held high government office under Margaret Thatcher and John Major (see: Cambridge University Conservative Association).[citation needed] According to Kenneth Clarke, Howard briefly defected to the Labour Party in 1961 in protest against the former's invitation to Oswald Mosley to speak to the CUCA. He had rejoined the Conservatives by next year.[11]

Howard was called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in 1964 and specialised in employment and planning law. He continued his career at the Bar, becoming a practising Queen's Counsel in 1982 (unlike some barrister-MPs who were awarded the title as an honorific despite no longer practising at the Bar).[12]

In the late 1960s Howard gained promotion within the Bow Group, becoming Chairman in April 1970. At the Conservative Party conference in October 1970, he made a notable speech commending the government for attempting to curb trade union power and also called for state aid to strikers' families to be reduced or stopped altogether, a policy which the Thatcher government pursued over a decade later.[citation needed]

In the 1970s, Howard was a leading advocate of British membership of the Common Market (EEC) and served on the board of the cross-party Britain in Europe group.[citation needed]

Marriage[edit]

In 1975, Howard married Sandra Paul. They have a son, born in 1976, and a daughter, born in 1977.[citation needed]

Member of Parliament[edit]

At the 1966 and 1970 general elections, Howard unsuccessfully contested the safe Labour seat of Liverpool Edge Hill; reinforcing his strong support for Liverpool F.C. which he has held since childhood.

In June 1982, Howard was selected to contest the constituency of Folkestone and Hythe in Kent after the sitting Conservative MP, Sir Albert Costain, decided to retire. Howard won the seat at the 1983 general election.

In Government[edit]

Howard gained quick promotion, becoming Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department of Trade and Industry in 1985 with responsibility for regulating the financial dealings of the City of London. This junior post became very important, as he oversaw the Big Bang introduction of new technology in 1986. Following the 1987 general election, he became Minister for Local Government. Following a proposal from backbench MP David Wilshire, he accepted the amendment which would become Section 28 (prohibiting local governments from the "promotion" of homosexuality) and defended its inclusion.

Howard guided the 1988 Local Government Finance Act through the House of Commons. The act brought in Margaret Thatcher's new system of local taxation, officially known as the Community Charge but almost universally nicknamed the "poll tax". Howard personally supported the tax and won Thatcher's respect for minimising the rebellion against it within the Conservative Party. After a period as Minister for Water and Planning in 1988–89, during which he was responsible for implementing water privatisation in England and Wales, Howard was promoted to the Cabinet as Secretary of State for Employment in January 1990 following the resignation of Norman Fowler. He subsequently guided through legislation abolishing the closed shop, and campaigned vigorously for Thatcher in the first ballot of the 1990 Conservative leadership election, although he told her a day before she resigned that he felt she was not going to win and that John Major was better placed to defeat Michael Heseltine.

He retained his Cabinet post under John Major and campaigned against trade union power during the 1992 general election campaign. His work in the campaign led to his appointment as Secretary of State for the Environment in the reshuffle following the election. In this capacity he encouraged the United States to participate in the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, but shortly afterwards he was appointed Home Secretary in a 1993 reshuffle precipitated by the sacking of Norman Lamont as Chancellor.

Home Secretary[edit]

As Home Secretary he pursued a tough approach to crime, summed up in his sound bite, "prison works". During his tenure as Home Secretary, recorded crime fell by 16.8%.[13] In 2010 Howard claimed a 45% decrease in crime since a 1993 study by Home Office criminologist Roger Tarling proved that prison worked though the prison population rose from 42,000 to nearly 85,000. Ken Clarke disagreed, pointing to a 60% recidivism rate amongst newly released prisoners and hinting that factors such as better household and vehicle security and better policing could be influencing crime rates, not just the incapacitation effect of removing offenders to prison.[14]

Howard repeatedly clashed with judges and prison reformers as he sought to clamp down on crime through a series of 'tough' measures, such as reducing the right to silence of defendants in their police interviews and at their trials as part of 1994's Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. Howard voted for the reintroduction of the death penalty for the killing of police officers on duty and for murders carried out with firearms in 1983 and 1990.[15] In 1993, he changed his mind and became opposed to the reintroduction of the death penalty and voted against it again in February 1994.

In 1993, following the murder of James Bulger, two eleven-year-old boys were convicted of his murder and sentenced to be detained at Her Majesty's pleasure, with a recommended a minimum term of eight years. Lord Taylor of Gosforth, the Lord Chief Justice, ordered that the two boys should serve a minimum of ten years.[16] The editors of The Sun newspaper handed a petition bearing nearly 280,000 signatures to Howard, in a bid to increase the time spent by both boys in custody.[17] This campaign was successful, and the boys were kept in custody for a minimum of fifteen years,[17][18] meaning that they would not be considered for release until February 2008, by which time they would be 25 years of age.[16]

A former Master of the Rolls, Lord Donaldson, criticised Howard's intervention, describing the increased tariff as "institutionalised vengeance ... [by] a politician playing to the gallery".[16] The increased minimum term was overturned in 1997 by the House of Lords, which ruled it was substantively ultra vires, and therefore "unlawful", for the Home Secretary to decide on minimum sentences for young offenders.[19] The High Court and European Court of Human Rights have since ruled that, though Parliament may set minimum and maximum terms for individual categories of crime, it is the responsibility of the trial judge, with the benefit of all the evidence and argument from both prosecution and defence counsel, to determine the minimum term in individual criminal cases.[18]

Controversies[edit]

Howard's reputation was damaged on 13 May 1997 when a critical inquiry into a series of prison escapes was published. In advance of the publication, Howard made statements blaming the prison service. In a television interview on Newsnight, Jeremy Paxman asked Howard whether he had intervened when Derek Lewis sacked a prison governor. Paxman asked "Did you threaten to overrule him?" twelve times. Howard repeatedly said that he "did not instruct him", ignoring the "threaten" part of the question.[20] Paxman asked him again in another interview in 2004. Howard responded: "Oh come on, Jeremy, are you really going back over that again? As it happens, I didn't. Are you satisfied now?" Secret Home Office papers partially vindicated Howard, but show that Howard asked a top civil servant if he had the power to overrule the Prison Service Director General.[21]

Shortly after the 1997 Newsnight interview, Ann Widdecombe, his former minister of state at the Home Office, made a statement in the House of Commons about the dismissal of then-Director of the Prison Service, Derek Lewis, and remarked of Howard that there is "something of the night" about him.[22] This much quoted comment is thought to have contributed to the failure of his 1997 bid for the Conservative Party leadership, including by Howard and Widdecombe,[23][24] and led to him being caricatured as a vampire, in part due to his Romanian ancestry.[25] Such characterisations caused discontent among members of Britain's Jewish community.

In 1996 Howard, as Home Secretary, ordered the release of John Haase and Paul Bennett with royal pardons after 10 months of their 18-year prison sentences for heroin smuggling, after they had provided information leading to the seizure of firearms. In 2008 Haase and Bennett were convicted of having set up the weapons finds to earn them their release, and sentenced to 20 and 22 years in prison respectively.[26]

First attempt to win party leadership[edit]

Following the 1997 resignation of John Major, Howard and William Hague ran on the same ticket, with Howard as leader and Hague as Deputy Leader and Party Chairman. The day after they agreed this, Hague decided to run on his own. Howard also stood but his campaign was marred by attacks on his record as Home Secretary.

Howard came in last out of five candidates with the support of only 23 MPs in the first round of polling for the leadership election. He then withdrew from the race and endorsed the eventual winner, William Hague. Howard served as Shadow Foreign Secretary for the next two years but retired from the Shadow cabinet in 1999, though continued as a backbench MP.

Leader of the Opposition[edit]

Following the Conservative defeat at the 2001 general election, Howard was recalled to frontline politics when the Conservative Party's new leader, Iain Duncan Smith, appointed him Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer. His performances in the post won him much praise; indeed, under his guidance, the Conservatives decided to debate the economy on an 'Opposition Day' for the first time in several years. After Duncan Smith was removed from the leadership, Howard was elected unopposed as leader of the party in November 2003. As leader, he faced much less discontent within the party than any of his three predecessors and was seen as a steady hand. He avoided repeating such managerial missteps as Duncan Smith's firing of David Davis as Conservative Party Chairman and imposed discipline quickly and firmly: for example, he removed the party whip from Ann Winterton after she joked about 23 Chinese migrants' deaths.

In February 2004, Howard called on then-Prime Minister Tony Blair to resign over the Iraq War, for failing to ask "basic questions" regarding WMD claims and misleading Parliament.[27] In July, the Conservative leader stated that he would not have voted for the motion that authorised the Iraq War had he known the quality of intelligence information on which the WMD claims were based. At the same time, he said he still believed in the Iraq invasion was right because "the prize of a stable Iraq was worth striving for".[28] However, Howard's criticism of Blair was not received favourably in Washington, D.C., where President of the United States George W. Bush refused to meet him. Bush's advisor Karl Rove reportedly told Howard, "you can forget about meeting the president. Don't bother coming."[29]

Howard was named 2003 Parliamentarian of the Year by The Spectator and Zurich UK. This was in recognition of his performance at the dispatch box in his previous role as Shadow Chancellor. However, twelve months after he became party leader, neither his personal popularity nor his party's with the public had risen appreciably in opinion polls from several years before.

Howard was part of discussions for British Airways to resume flights to Pakistan in 2003, this was until their final departure in 2008 the only European airline serving the nation.[30]

Further Newsnight treatment[edit]

In November 2004, Newsnight again concentrated on Howard with coverage of a campaign trip to Cornwall and an interview with Jeremy Paxman. The piece, which purported to show that members of the public could not identify Howard and that those who recognised him did not support him, was the subject of an official complaint from the Conservative Party. The complaint argued that the Newsnight team spoke only to people who held opinions against either Michael Howard or the Conservatives and that Paxman's style was bullying and unnecessarily aggressive. In this programme, Paxman also returned to his question from 1997. Howard returned briefly to Newsnight on Jeremy Paxman's final episode on 18 June 2014 for a cameo.

2005 general election[edit]

At the 2005 general election, Howard's Conservative Party suffered a third consecutive defeat, although the Conservatives gained 33 seats (including five from the Liberal Democrats) and Labour's majority shrank from 167 to 66. The Conservatives were left with 198 seats to Labour's 355. The Conservative share of the national vote increased by 0.6% from 2001 and 1.6% from 1997. The party ended with 32.4% of the total votes cast, which was within 3% of Labour on 35.2%.

The day after the election, Howard stated in a speech in the newly gained Conservative seat in Putney that he would not lead the party into the next general election as, already aged 63, he would be "too old" by that stage, and that he would stand down "sooner rather than later", following a revision of the Conservative leadership electoral process. Despite Labour winning a third term in government, Howard described the election as "the beginning of a recovery" for the Conservative Party following Labour's landslide victories in 1997 and 2001.[31]

Howard's own constituency of Folkestone and Hythe had been heavily targeted by the Liberal Democrats as the most sought after prize of their failed "decapitation" strategy of seeking to gain seats from prominent Conservatives. Yet Howard almost doubled his majority to 11,680, while the Liberal Democrats saw their vote fall.

Criticism of 2005 campaign[edit]

During the 2005 general election campaign, Howard was criticised by some commentators for conducting a campaign which addressed the issues of immigration, asylum seekers, and travellers.[32][33] Others[like whom?] noted that the continued media coverage of such issues created most of the controversy and that Howard merely defended his views when questioned at unrelated policy launches.[citation needed]

Some evidence suggested that the public generally supported policies proposed by the Conservative Party when they were not told which party had proposed them, indicating that the party still had an image problem. Conservative John Major's 30% lead in 1992 amongst the sought after ABC1 voters (professionals) had all but disappeared by 2005.[34]

The campaign focus on immigration may have been influenced by Howard's election adviser Lynton Crosby, who had run similar tactics in Australian elections earlier.[35] Crosby was later re-hired by the Conservative Party to run their successful campaign in the 2008 London mayoral election.[citation needed]

In the lead up to the election campaign, Howard continued to impose strong party discipline, controversially forcing the deselection of Danny Kruger (Sedgefield), Robert Oulds and Adrian Hilton (both Slough) and Howard Flight (Arundel & South Downs).[36]

Resignation[edit]

Despite his impending resignation following the 2005 general election, Howard performed a substantial reshuffle of the party's front bench in which several rising star MPs were given their first shadow portfolios, including George Osborne and David Cameron. This move cleared the way for David Cameron (who had worked for Howard as a Special Advisor when the latter was Home Secretary) to run for the Conservative Party leadership.

The reforms to the party's election process took several months and Howard remained in his position for six months following the election. During that period, he enjoyed a fairly pressure-free time, often making joking comparisons between himself and Tony Blair, both of whom had declared they would not stand at the next general election. He also oversaw Blair's first parliamentary defeat, when the Conservative Party, the Liberal Democrats and sufficient Labour Party rebels voted against government proposals to extend to 90 days the period that terror suspects could be held for without charge. Howard stood down as Leader in December 2005 and was replaced by David Cameron.

Retirement[edit]

Howard announced on 17 March 2006 that he would stand down as MP for Folkestone and Hythe at the 2010 general election.[37] On 13 July 2006 the Conservatives selected Damian Collins to stand in his place at that election.

On 19 June 2006 it was reported that Howard would become chairman of Diligence Europe, a private intelligence and risk assessment company founded by former CIA and MI5 members.[38][39]

On 23 October 2006, Howard said that he had voluntarily been questioned as a potential witness as part of the investigation into the Cash-for-Honours scandal relating to fundraising for the 2005 election campaign. He was not suspected of any criminal activity,[40] was not accused of any criminal activity and gave evidence purely as a witness in an investigation focusing primarily on the Labour Government's use of the peerages system and their party fundraising.

Howard was appointed a Conservative life peer in the 2010 Dissolution Honours with the title of Baron Howard of Lympne, of Lympne in the County of Kent.[41][42] On 20 July 2010, he was formally introduced into the House of Lords by past colleague Norman Lamont, and attended Questions and debate later that day.[43]

In 2010, David Cameron wanted Howard to join his Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, possibly as Lord Chancellor, via the House of Lords as part of David Cameron's appeal to rightwing Tories. However, it did not happen, Howard having criticised the government's proposal for a 'rehabilitation revolution'.[44]

In February 2011 there was increased speculation that Cameron would reshuffle his cabinet, with Lord Howard brought in to replace Kenneth Clarke as Secretary of State for Justice. Instead, Chris Grayling was appointed.[45][46]

Howard was appointed a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour in the 2011 Birthday Honours for public and political services.[47][48]

A few days after Article 50 was triggered for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, Howard was interviewed on 2 April 2017 by Sophy Ridge for her programme on Sky News. He compared the post-Brexit situation of Gibraltar's disputed sovereignty with Spain with the resolution of a similar issue by the Falklands War in 1982. Howard said he was "absolutely certain" Theresa May "will show the same resolve in standing by the people of Gibraltar" as Margaret Thatcher had done in the South Atlantic. Leading figures from the other parties rejected this viewpoint.[49][50] A spokesman for Number 10 said such a conflict "isn't going to happen".[51]

In June 2022, Howard called on Boris Johnson to resign as Prime Minister.[52]

Criticism of Somali business interests[edit]

In 2015, Soma Oil & Gas, which Howard chairs, was investigated by the Serious Fraud Office.[53] On 14 December 2016, the SFO closed its investigation of Soma, citing insufficient evidence of corruption.[54]

Charity work[edit]

Howard is a keen supporter of the hospice movement and was chairman of Hospice UK from 2010 until 2018.[55]

Arms[edit]

|

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Howard of Lympne, Baron, (Michael Howard) (born 7 July 1941)". Who's Who & Who Was Who. 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u20909. ISBN 978-0-19-954088-4. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "No Brexit unless we back Theresa May, Jeremy Hunt says". BBC News. 3 December 2017. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ O'Grady, Sean (13 April 2002). "Michael Howard: Out of the shadows". The Independent. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2002.

- ^ "How Bernat Hecht, father of the Home Secretary, sought asylum". The Independent. 19 November 1995. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Vasagar, Jeevan (1 November 2003). "From Transylvania to Smith Square". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Jones, George (22 March 2005). "'Gas chambers' row over Tory gipsy law". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Vasagar, Jeevan (1 November 2003). "From Transylvania to Smith Square". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "Michael Howard recalls father's death from breast cancer". Itv.com. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Nick (2 November 2003). "What's in a name?". The Observer. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ "No. 38207". The London Gazette. 13 February 1948. p. 1048.

- ^ Clarke, Ken (6 October 2016). Kind of Blue: A Political Memoir. Pan Macmillan. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-5098-3724-3.

- ^ "Notable Members | Inner Temple". The Inner Temple. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Channel 4 News, FactCheck: Spoof Howard Cv needs policing

- ^ Alan Travis (7 December 2010). "Howard is right: 'prison works' – but this is no way to cut crime". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ "DEATH PENALTY FOR MURDER (Hansard, 17 December 1990)". Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004). "Bulger, James Patrick (1990–1993), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/76074. Retrieved 2 October 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (Subscription Required)

- ^ a b "James Bulger killing: the case history of Jon Venables and Robert Thompson". The Guardian. London. 3 March 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. The Guardian (London) 3 March 2010.

- ^ a b "New sentencing rules: Key cases". BBC News. 7 May 2003. Archived from the original on 30 July 2004. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "Outrage at call for Bulger killers' release". BBC. 28 October 1999. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Newsnight – Jeremy Paxman biography". BBC News. 10 October 2006. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Travis, Alan (2 March 2005). "Secret Home Office papers on prison row fail to clear Howard". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Sengupta, Kim; Abrams, Fran (12 May 1997). "Widdecombe goes for the jugular". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ "Ann Widdecombe 'tested out' Howard quip". BBC News. 31 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Crick, Michael (30 March 2005). "'Mission accomplished': how Howard was knifed". The Times. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.(subscription required) Extract from Crick's book In search of Michael Howard.

- ^ Holland, David (3 May 2011). "Interview with a Vampire". The Tab. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Summers, Chris. "How a home secretary was hoodwinked". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ "Howard calls for Blair to resign". BBC News. 5 February 2004. Archived from the original on 9 July 2004. Retrieved 28 August 2004.

- ^ "At-a-glance Iraq debate". BBC News. 20 July 2004. Archived from the original on 26 July 2004. Retrieved 28 August 2004.

- ^ "Howard hits out at Bush aides". BBC News. 28 August 2004. Archived from the original on 29 August 2004. Retrieved 28 August 2004.

- ^ "BA flies back to Pakistan". 2 December 2003. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Howard will stand down as leader". BBC News. 6 May 2005. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Tempest, Matthew (24 January 2005). "Howard calls for asylum cap". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ McSmith, Andy (20 March 2005). "Howard stirs race row with attack on Gypsies". The Independent. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "News and debate from the progressive community". progressives.org.uk. 20 April 2018.[permanent dead link]. Progressives.org.uk. Retrieved on 15 August 2013.[dead link]

- ^ "Lynton Crosby globetrotting, spreading dirty dog whistles". Fixing Australia. 18 April 2005. Archived from the original on 22 June 2005. Retrieved 7 May 2005.

- ^ Peter Preston (28 March 2005). "The brutal world of Spin Doctor Who". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Michael Howard stands down as MP". BBC News. 17 March 2006. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Former Tory leader to head risk firm". International Herald Tribune. 19 June 2006. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ "Diligence announces addition of Michael Howard to Advisory Board". Diligencellc.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Howard quizzed in honours probe". BBC News. 23 October 2006. Archived from the original on 7 November 2006.

- ^ "No. 59491". The London Gazette. 19 July 2010. p. 13713.

- ^ "Peerages, honours and appointments". 10 Downing Street. 28 May 2010. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "House of Lords Future Business". parliament.uk. 20 July 2010.

- ^ Dale, Iain; Brivati, Brian (4 October 2010). "Top 100 most influential Right-wingers: 75-51". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010.

- ^ Stratton, Allegra (20 February 2011). "Kenneth Clarke offers hope to Tory critics of human rights court". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Helm, Toby (19 February 2011). "Tory MPs press David Cameron for cabinet reshuffle". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "No. 59808". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 June 2011. p. 26.

- ^ "The Queen's Birthday Honours List 2011". Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 2011-06-11. Cabinet Office, 11 June 2011.

- ^ Asthana, Anushka (2 April 2017). "Theresa May would go to war to protect Gibraltar, Michael Howard says". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Peck, Tom (2 April 2017). "Brexit could turn Gibraltar in to the next Falklands, senior Conservatives suggest". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Watts, Joe (3 April 2017). "Downing Street defends ex-Tory leader Michael Howard's claim UK would go to war with Spain over Gibraltar". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ "By-election defeats: Ex-leader Michael Howard calls for Boris Johnson to go". BBC News. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Justin Scheck and Jenny Gross (25 August 2015). "Report Raises Questions Over Somali Dealings of Firm Headed by U.K.'s Michael Howard". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ "Serious Fraud Office Closes Corruption Investigation of Soma Oil". WSJ Risk and Compliance Journal. 15 December 2016. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Hospice UK Chair set to retire from board later this year". hospiceuk.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Debrett's Peerage. 2019. p. 3068.

External links[edit]

- Michael Howard MP official site

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Michael Howard

- Conservative Party: Michael Howard official profile of the Party Leader

- ePolitix.com – Michael Howard Archived 25 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine profile

- Guardian Unlimited Politics – Ask Aristotle: Michael Howard MP

- They Work For You: Michael Howard MP

- The Public Whip – Michael Howard MP voting record

- BBC News – Michael Howard profile 17 October 2002

- Michael Howard on Newsnight on YouTube

- Debrett's People of Today

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1941 births

- Alumni of Peterhouse, Cambridge

- British people of Romanian-Jewish descent

- British people of Russian-Jewish descent

- English King's Counsel

- British Secretaries of State for Employment

- British Secretaries of State for the Environment

- Conservative Party (UK) life peers

- Life peers created by Elizabeth II

- Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- Jewish British politicians

- Leaders of the Conservative Party (UK)

- Leaders of the Opposition (United Kingdom)

- Living people

- Members of the Bow Group

- Members of the Inner Temple

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- People educated at Llanelli Boys' Grammar School

- People from Llanelli

- Politicians from Swansea

- Presidents of the Cambridge Union

- Secretaries of State for the Home Department

- UK MPs 1983–1987

- UK MPs 1987–1992

- UK MPs 1992–1997

- UK MPs 1997–2001

- UK MPs 2001–2005

- UK MPs 2005–2010

- Welsh Jews

- Welsh lawyers

- Welsh politicians

- 20th-century Welsh lawyers

- Shadow Chancellors of the Exchequer

- Jewish nobility