Margo St. James

Margo St. James | |

|---|---|

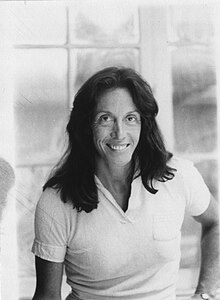

Photograph of St. James by filmmaker George Csicsery | |

| Born | Margaret Jean St. James September 12, 1937 Bellingham, Washington, US |

| Died | January 11, 2021 (aged 83) Bellingham, Washington, US |

| Occupation | Feminist activist |

| Known for | Founder of St. James Infirmary Clinic and COYOTE |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Don Sobjack, Jr. |

Margaret Jean "Margo" St. James (September 12, 1937 – January 11, 2021) was an American sex worker and sex-positive feminist. In San Francisco, she founded COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), an organization advocating decriminalization of prostitution, and co-founded the St. James Infirmary Clinic, a medical and social service organization serving sex workers in the Tenderloin.

Early life and education[edit]

St. James was born on 12 September 1937 in Bellingham, Washington, to George, a dairy farmer and Dorothy, a secretary.[1] She was the oldest of three children; her sister is a gospel singer and her brother is a sailor.[2] Growing up, Peggy, as she was called then, attended Bellingham High School and established herself as a realist painter. After she entered and won a New York contest, one of her works was chosen to be displayed at Carnegie Hall.[1][3]

She married Don Sobjack one month after her graduation and they had a son soon after.[3] Reflecting on her catapult into early parenthood, St. James told The Guardian that she knew it was “a mistake” and believed she would be a “bad mother”. In 1958, she divorced her husband and left for art school in San Francisco.[4]

Career[edit]

After her marriage ended, she moved to the heart of beatnik San Francisco to pursue an art career, living first in North Beach and then Haight-Ashbury. She lost all her canvasses to theft and a fire at her studio.[3]

In the 1960s, while she worked as a cocktail waitress, her apartment in Haight served as an informal salon; she lived with guitarist Steve Mann and hosted visitors including Ken Kesey, Dr. John, Frank Zappa, members of comedic improvisational ensemble The Committee, and comedian and publisher Paul Krassner. In a 2011 interview with Chicago's The Windy City Times, St. James recalled that "a lot of friends came over to her house after work, and there was a lot of pot-smoking and sex and, you know, whatever". The police became suspicious about the volume of people coming from and going to her house, and in 1962, she was arrested and falsely accused of prostitution. In court, St. James argued that she had “never turned a trick in her life” but was shot down by the judge who believed that "anyone who knows the language is a professional". She was convicted and jailed briefly.[1]

Infuriated by the outcome, St. James appeared for the college equivalency examination and enrolled in law school. She successfully appealed her conviction, worked as a process server for criminal defense attorney Vincent Hallinan, and became one of the first women private investigators in California.[5]

The conviction excluded her from many jobs, so, she wrote in 1989, and she became both a sex worker and a feminist.[3] She listed restaurant hostess, valet parking attendant, and deckhand on dinner cruises as other jobs she had held.[6]

During 1970–73, she was living in Marin County with carpenter-musician Roger Somers. Her next door neighbour was Elsa Gidlow, a lesbian poet, who pushed feminist literature under her door. In 1973, St. James founded COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics) to push for financial security, health care, and legal rights for sex workers. Its forerunner was Whores, Housewives and Others (WHO), the "others" being lesbians.[3] The first meeting of WHO took place in 1972 on Alan Watts’ houseboat (“The Vallejo”) in Sausalito.[2]

The name COYOTE came from the author Tom Robbins, who dubbed St. James the 'COYOTE Trickster' after one of their "mushroom-hunting expeditions."[2] The group was instrumental in the fight against San Francisco policies requiring arrested sex workers to undergo mandatory testing for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and face quarantine if the test came back positive. In the process, St. James worked towards reframing prostitution as a lawful profession with legitimate workplace and human rights concerns instead of something sinful.[1]

To finance COYOTE and its newspaper, COYOTE HOWLS, she organized annual Hooker's Balls;[5] the highest attendance was 20,000 in 1978.[3][6][7] She also organized similar organizations in other states,[5] lectured in 1974 on college campuses including Harvard, and in 1976 attended both the Democratic and Republican National Conventions, organizing "loiter-ins" at the former.[citation needed] In 1984, with the scholar Gail Pheterson and coinciding with the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, she organized the Women's Forum on Prostitutes' Rights and the COYOTE Convention.[5] She also attended the United Nations Decade Face of Women Conferences in Mexico City, the 1976 Tribunal of Crimes Against Women in Brussels, the 1977 International Women's Year Conference in Houston, the 1977 Libertarian Party Convention, and the 1980 Decade of Women Conference in Copenhagen.[citation needed]

From 1985 to 1994 she lived with Pheterson in the Netherlands and then the South of France. They co-founded the International Committee for Prostitutes' Rights and organized the first and second World Whores' Congresses, held in Amsterdam in 1985 and at the European Parliament in Brussels in 1986, which led to the World Charter for Prostitutes' Rights.[5][6]

After her return from Europe, in the 1990s she was appointed to the San Francisco Task Force on Prostitution and in 1999 was one of three founders of the St. James Infirmary Clinic in the Tenderloin, which provides health care to the sex worker community.[3][5][8] She also served on the Board of Supervisors' Drug Abuse Advisory Board.[9]

St. James sought the Republican Party nomination for President of the United States in 1980 but the extent of her efforts is unknown.[8][10] In 1996, she campaigned for a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and promised to install a red light outside the City Hall that would be turned on whenever she was present.[6] Her famous slogan "The Lady Is a...Champ" was coined by longtime associate, chairperson of the California Democratic Party, and former member of US Congress John Burton.[11] She claimed to have the support of "the bohemians, the old hippies, the gays" in addition to "the veterans and the longshoremen and the politicians".[4] St. James also received endorsements from Mayor Willie Brown and the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, among others, but ultimately lost the election.

Personal life and death[edit]

St. James was first married to Don Sobjack, a fisherman; they married soon after she graduated from high school and had one son, Don Jr.[3][8][6]

In addition to Steve Mann and Gail Pheterson, St. James's partners included the psychiatrist Eugene Schoenfeld, known as "Dr. Hip".[3]

She married long-time friend and retired Bay Area journalist Paul Avery on Valentine’s Day in 1992. He was fatally ill with emphysema, and proposed so she could share his healthcare and also take care of him.[1] The couple lived in her family cabin in Orcas Island, Washington, where she remained until after he died in 2000.[12] After she started showing signs of Alzheimer’s, her sister, Claudette Sterk, moved her back to the mainland. She was diagnosed in June 2020, and died on January 11, 2021, at a memory care facility in Bellingham, Washington.[3][13][1] She has three grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.[1]

COYOTE's and St. James's papers are archived at Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University.[5][14]

Bibliography[edit]

- Pheterson, Gail, ed. (June 1989). A Vindication of the Rights of Whores. Seal Press. ISBN 978-0-931188-73-2.

Filmography[edit]

Margo St. James starred in:

- Dreamwood, an experimental film by James Broughton (1972)[15]

- Hookers, a documentary by George Csicsery (1975)[16]

- Hard Work, a documentary short by Ginny Durrin (1978)[17]

- Happy Endings?, a documentary by Tara Hurley (2009)

She also received a "Special Thanks" screen credit for the 1986 adult film Behind the Green Door: The Sequel[18]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Seelye, Katharine Q. (2021-01-20). "Margo St. James, Advocate for Sex Workers, Dies at 83". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ a b c "Margo St. James – St. James Infirmary". Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sam Whiting (January 15, 2021). "Margo St. James, the sex workers' 'Joan of Arc,' dies at 83". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Margo St. James, outspoken advocate for sex workers, dies at 83". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g "San Francisco's Own Legendary Margo St. James Dies". St. James Infirmary. January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Emily Langer (January 15, 2021). "Margo St. James, saucy advocate for sex workers, dies at 83". Washington Post. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Stephen Dyer Wells. "The Unofficial Margo St. James Fan Club". Archived from the original on July 20, 2001.

- ^ a b c Dan Gentile (January 13, 2021). "Legendary SF sex worker activist Margo St. James dies at age 83". SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle). Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ San Francisco Board of Supervisors (December 20, 1999). "Agenda & Minutes Archive". City and County of San Francisco. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ Don Stannard-Friel (2016). Street Teaching in the Tenderloin: Jumpin' Down the Rabbit Hole. Springer. p. 148. ISBN 9781137564375.

- ^ "The lady was a champ: Remembering Margo St. James, patron saint of sex work". 48 hills. 2021-01-22. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ Anne Gray Fischer (February 11, 2013). "Forty Years In The Hustle: A Q&A With Margo St. James". bitchmedia.org. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ Joe Kokura (January 13, 2021). "Margo St. James, Matriarch of the Modern Sex Work Movement, Has Died". Broke-Ass Stuart. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ Dick Boyd. "Margot St. James". North Beach Book.

- ^ "Dreamwood (1972)". IMDb.

- ^ Hookers on IMdB

- ^ "Hard Work (1978) [Short]". MIFF.

- ^ "Behind the Green Door: The Sequel". IMDb.

External links[edit]

- Coyote (Organization). Records, 1962-1989: A Finding Aid housed at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Radcliffe College

- Margo St. James for San Francisco Board of Supervisors, archived on October 13, 1997

- Speech by Dorchen Liedholdt, attacking Margo St. James

- 1937 births

- 2021 deaths

- People from Bellingham, Washington

- American feminists

- American women's rights activists

- Sex worker activists in the United States

- Feminist studies scholars

- Sex-positive feminists

- American prostitutes

- Activists from Washington (state)

- Candidates in the 1980 United States presidential election

- Candidates in the 1996 United States elections