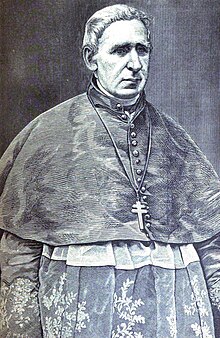

John MacHale

The Most Reverend John MacHale | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Tuam | |

| |

| Native name | Irish: Seán Mac Éil |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| Archdiocese | Tuam |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1814 by Daniel Murray |

| Consecration | 1825 by Pope Leo XII |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 March 1789 (or 1791) Tubbernavine, County Mayo, Ireland |

| Died | 7 November 1881 (aged 90 or 92) Tuam, County Galway, Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

John MacHale[1] (Irish: Seán Mac Éil;[2] 6 March 1789 (or 1791) – 7 November 1881) was the Irish Roman Catholic Archbishop of Tuam, and Irish nationalist.

He laboured and wrote to secure Catholic Emancipation, legislative independence, justice for tenants and the poor, and vigorously assailed the proselytizers and the government's proposal for a mix-faith national school system. He preached regularly to his flock in Irish and "almost alone among the Bishops he advocated the use of Irish by the Catholic clergy".[3]

Childhood[edit]

John MacHale was born in Tubbernavine, near Lahardane, County Mayo, Ireland.[4] Bernard O'Reilly places the date in the spring of 1791,[5] while others suggest 1789 more likely.[6] His parents were Patrick and Mary (née Mulkieran) MacHale. He was so feeble at birth that he was baptised at home by Father Andrew Conroy, who later was hanged during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. His father, known locally as Pádraig Mór, was a farmer, whose house served as a wayside inn on the highroad between Sligo and Castlebar. Although Irish was always spoken by the peasants at that time, the MacHale children were all taught English.[citation needed] John's grandmother, however, encouraged him to retain his knowledge of Irish.

By the time he was five years of age, he began attending a hedge school.[6] [7] Three important events happened during John's childhood: the Irish Rebellion of 1798; the landing at Killala of French troops, whom the boy, hidden in a stacked sheaf of flax, watched marching through a mountain pass to Castlebar; and a few months later the execution of Father Conroy on a charge of high treason. These occurrences made an indelible impression upon him.[5]

After school hours he studied Irish history, under the guidance of an old scholar in the neighbourhood. Destined for the priesthood, at the age of thirteen he was sent to a school at Castlebar to learn Latin, Greek, and English grammar.[6] In his sixteenth year the Bishop of Killala gave him a busarship at St Patrick's College, Maynooth at Maynooth.[8]

Ordination[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

The emigrant French priests who then taught at Maynooth appreciated the linguistic aptitude of the young man and taught him not only French, but also Latin, Greek, Italian, German, Hebrew, and the English classics. After seven years of study, he was appointed in 1814 lecturer in theology, although only a sub-deacon. Before the end of the year, however, aged 23 or 25, he was ordained a priest by Daniel Murray, Archbishop of Dublin.[5] Father MacHale continued his lectures at Maynooth until 1820, when he was nominated professor of theology.

About this period he commenced a series of letters to the Dublin Journal, signed "Hierophilus", vigorously attacking the Irish Established Church's system of religious education in schools. [7]

In 1825, Pope Leo XII appointed him titular bishop of Maronia, and coadjutor bishop to Dr. Thomas Waldron, Bishop of Killala.[9] After his consecration in Maynooth College chapel, he devoted himself to his sacred duties. He preached Irish and English sermons, and superintended the missions given in the diocese for the Jubilee of 1825. The following year, MacHale joined Bishop Doyle in denouncing the proselytizing Kildare Street Society of Dublin.[9]

MacHale attended the annual meeting of the Irish bishops, and gave evidence at Maynooth College before the Parliamentary Commissioners then inquiring into the condition of education in Ireland. The Catholic hierarchy's policy in the following decades was to ensure that Irish primary schools for Catholic children were run by Catholics, while the Dublin administration wanted all such schools to be run on a mixed-faith basis. The officials felt that two parallel systems would be too expensive and socially divisive, but the hierarchy held this would result in a default system based on the English version of history that had often been anti-Catholic since 1570.

Emancipation campaign, 1820s[edit]

About this time he also revised a theological manual On the Evidences and Doctrines of the Catholic Church, afterward translated into German. With his friend and ally, Daniel O'Connell, MacHale took a prominent part in the important question of Catholic Emancipation, impeaching in unmeasured terms the severities of the former penal code, which had branded Catholics with the stamp of inferiority. During 1826 his zeal was omnipresent; "he spoke to the people in secret and public, by night and by day, on the highways and in places of public resort, calling up the memories of the past, denouncing the wrongs of the present, and promising imperishable rewards to those who should die in the struggle for their faith. He called on the Government to remember how the Act of Union in 1800 was carried by William Pitt the Younger on the distinct assurance and implied promise that Catholic Emancipation, which had been denied by the Irish Parliament, should be granted by the Parliament of the Empire."[10]

1830s[edit]

In two letters written to the Prime Minister, Earl Grey, he described the distress occasioned by starvation and fever in Connacht, the ruin of the linen trade, the vestry tax for the benefit of Protestant churches, the tithes to the Protestant clergy, which Catholics were obliged to pay as well as their Protestant countrymen, the exorbitant rents extracted by absentee landlords, and the crying abuse of forcing the peasantry to buy seed-corn and seed-potatoes from landlords and agents at usurious charges. No attention was paid to these letters. Dr. MacHale accompanied to London a deputation of Mayo gentlemen, who received only meaningless assurances from Earl Grey. After witnessing the coronation of William IV at Westminster Abbey, the bishop, requiring change of air on account of ill-health, went on to Rome, but not before he had addressed to the premier another letter informing him that the scarcity in Ireland "was a famine in the midst of plenty, the oats being exported to pay rents, tithes, etc., and that the English people were actually sending back in charity what had originally grown on Irish soil plus freightage and insurance". It may be observed that Dr. MacHale never blamed the English people, whose generosity he acknowledged. On the other hand he severely condemned the Government for its incapacity, its indifference to the wrongs of Ireland, that aroused in the Irish peasantry a sullen hatred unknown to their more simple-minded forefathers. During an absence of sixteen months he wrote excellent descriptive letters of all he saw on the Continent. They were eagerly read in The Freeman's Journal, while the sermons he preached in Rome were so admired that they were translated into Italian. Amid the varied interests of the Eternal City he was ever mindful of Ireland's woes and forwarded thence another protest to Earl Gray against tithes, and proselytism, this last grievance being then rampant, particularly in Western Connacht.

On his return he became an opponent of the proposed system of non-sectarian 'National Schools', fearing that the bill as originally framed, was an insidious attempt to weaken the faith of Catholic children. The policy of the Stanley letter was to provide a new state-funded primary school system without religious indoctrination. McHale's overview was that in many ways he owned his flock, body and soul, and would educate them as he saw fit.

Archbishop of Tuam[edit]

| Styles of John MacHale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | The Most Reverend |

| Spoken style | Your Grace or Archbishop |

Oliver Kelly, Archbishop of Tuam, died in 1834, and the clergy selected MacHale as one of three candidates, to the annoyance of the Government who despatched agents to induce the pope not to nominate him to the vacant see. Pope Gregory XVI dryly remarked:

- ever since the Relief Bill had passed, the English Government never failed to interfere about every appointment as it fell vacant" (Charles C. F. Greville, "Memoirs", pt. II[11]).

Disregarding their request, the pope appointed MacHale Archbishop of Tuam. He was the first prelate since the Reformation who had received his entire education in Ireland. The corrupt practices of general parliamentary elections and the Tithe War caused frequent rioting and bloodshed, and were the subjects of denunciation by the new archbishop, until the passing of a Tithes bill in 1838. Archbishop MacHale now began in the newspapers a series of open letters to the Government, whereby he frequently harassed the ministers into activity in Irish affairs. MacHale also led the opposition to the Protestant Second Reformation, which was being pursued by evangelical clergy in the Church of Ireland, including the Bishop of Tuam, Thomas Plunket.

During the Autumn of 1835, he visited the Island of Achill, a stronghold of the Bible Readers. To offset their proselytism, he sent thither more priests and Franciscan friars of the Third Order.

MacHale condemned the Poor Law, and the system of National Schools and Queen's Colleges as devised by the Government. He founded his own schools, entrusting those for boys to the Christian Brothers and Franciscan friars, while Sisters of Mercy and Presentation Nuns taught the girls. Want of funds restricted the number of these schools, which had to be supplemented by the National Board at a later period, when the necessary amendments had been added to the Bill.

Repeal of the Union campaign, 1830s[edit]

The repeal of the Union, advocated by Daniel O'Connell, enlisted his ardent sympathy and he assisted the Liberator in many ways, and remitted subscriptions from his priests for this purpose. His biographer Bernard O'Reilly describes MacHale as supporting "a thorough and universal organisation of Irishmen in a movement for obtaining by legal and peaceful agitation the restoration of Ireland's legislative independence".[12] The Charitable Bequests Bill, formerly productive of numerous lawsuits owing to its animus against donations to religious orders, was vehemently opposed by the archbishop. In this he differed considerably from some other Irish prelates, who thought that each bishop should exercise his own judgment as to his acceptance of a commissionership on the Board, or as regarded the partial application of the Act. The latter has since then been so amended, that in its present form it is quite favourable to Catholic charities and the Catholic poor. In his zeal for the cause of the Catholic religion and of Ireland, so long down-trodden, but not in the 1830s, Dr. MacHale frequently incurred from his opponents the charge of intemperate language, something not altogether undeserved. He did not possess that suavity of manner which is so invaluable to leaders of men and public opinion, and so he alarmed or offended others. In his anxiety to reform abuses and to secure the welfare of Ireland, by an uncompromising and impetuous zeal, he made many bitter and unrelenting enemies. This was particularly true of British ministers and their supporters, by whom he was dubbed "a firebrand", and "a dangerous demagogue". Cardinal Barnabo, Prefect of Propaganda, who had serious disagreements with Dr. MacHale, declared he was a twice-dyed Irishman, a good man ever insisting on getting his own way. This excessive inflexibility, not sufficiently tempered by prudence, explains his more or less stormy career.

The Famine of 1845–49[edit]

The Irish famine of 1846–47 affected his diocese more than any. In the first year he announced in a sermon that the famine was a divine punishment on his flock for their sins (as did Cardinal Wiseman). Then by 1846 he warned the Government as to the state of Ireland, reproached them for their dilatoriness, and held up the uselessness of relief works expended on high roads instead of on quays and piers to develop the sea fisheries. From England as well as other parts of the world, cargoes of food were sent to the starving Irish. Bread and soup were distributed from the archbishop's kitchen. Donations sent to him were acknowledged, accounted for, and disbursed by his clergy among the victims.

Political matters[edit]

The death of Daniel O'Connell in 1847 was a setback to MacHale as were the subsequent disagreements within the Repeal Association.

The 1850 Synod of Thurles emphasised differences within the hierarchy on education with MacHale strongly in favour of exclusively Catholic institutions, along with Papal policy.

During the recrudescence of "No Popery" in 1851, on the occasion of the re-establishment of the Catholic Hierarchy in England and Wales, and the passing of the Ecclesiastical Titles Act that inflicted penalties upon any Roman Catholic prelate who assumed the title of his see, MacHale defiantly signed his letters to Government on this subject "John, Archbishop of Tuam".

As to the Catholic University, although MacHale had been foremost in advocating the project, he disagreed completely with Paul Cullen, Archbishop of Dublin, concerning its management, particularly the appointment of John Henry Newman as rector – a disagreement that handicapped the new university.

MacHale approved of the Irish Tenant League. He wrote to O'Connell's son that it "was the assertion of the primitive right of man to enjoy in security and peace the fruit of his industry and labour". At a conference held in Dublin, there was cross-denominational support for his views on "fixity of tenure, free sale, and fair rent", and these were provided for in the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870.

Vatican Council[edit]

MacHale attended the First Vatican Council of 1869–1870. He voted against the doctrine of papal infallibility on the first ballot on the basis that it was an inopportune time to promulgate it; he absented himself from the final ballot, which adopted it.[13] According to Bernard O'Reilly, "on his return to Tuam he lost not a moment in proclaiming from the pulpit of St Jarlath's the dogma ..., which he believed with his whole heart and mind, as he believed the articles of the Apostles' Creed".[14]

A character in James Joyce's story "Grace" tells a garbled version of the events, conflating MacHale with Edward Fitzgerald, another no-voter.[13]

In 1877, to the disappointment of the archbishop, who desired that his nephew should be his coadjutor, John McEvilly, Bishop of Galway, was elected by the clergy of the archdiocese, and was commanded by Pope Leo XIII after some delay, to assume his post. He had opposed this election as far as possible, but submitted to the papal order.[citation needed]

Use of Irish[edit]

Every Sunday he preached a sermon in Irish at the cathedral, and during his diocesan visitations he always addressed the people in their native tongue, which was still largely used in his diocese. On journeys he usually conversed in Irish with his attendant chaplain, and had to use it to address people of Tuam or the beggars who greeted him whenever he went out. He preached his last Irish sermon after his Sunday Mass, April 1881. He died seven months later.

Memorials[edit]

A marble statue perpetuates his memory in the Cathedral grounds.

The Cork-born Irish-American composer Paul McSwiney (1856–1890) was in the process of writing the cantata John McHale for centenary celebrations in New York City in 1891, but died before he could complete it.[15]

MacHale Park in Castlebar, County Mayo and Archbishop McHale College in Tuam are named after him.

In his birthplace, the Parish of Addergoole, the local GAA Club Lahardane MacHales is named in his honour. The Dunmore GAA team, "Dunmore MacHales", which play underage teams to senior teams, is also named after him.[16]

Works[edit]

Among his writings are a treatise on the evidences of Catholicism and translations in Irish of Moore's "Melodies," and part of the Bible and the Iliad. He compiled an Irish language catechism and prayer book. Moreover, he made translations into Irish of portions of the scriptures as well as the Latin hymns, Dies Irae and Stabat Mater.

Notes[edit]

- ^ The spelling MacHale is adopted by the Catholic Hierarchy site, and his biographer.

- ^ The original publication of MacHale's translation of the Iliad gave his name as "Seághan, Árd-Easbog Túama" (sic), i.e. "John, Archbishop of Tuam.[1] In later contexts, MacHale's name is usually given as Seán Mac Héil or Seán Mac hÉil. A 1981 reprint of MacHale's translation of the Iliad, Íliad Hóiméar, leabhair I-VIII, gives his name as Seán Mac Héil.[2] Áine Ní Cheanainn's Leon an Iarthair : aistí ar Sheán Mac Héil, Ardeaspag Thuama, 1834–1881 (1983) also uses Seán Mac Héil.[3] However, Peter A. Maguire's "Language and Landscape in the Connemara Gaeltacht" in the Journal of Modern Literature (26.1, Fall 2002, pp. 99–107) uses Seághan Mac Éil and the name is also given as Eoin Mac Héil by some sources.[4]

- ^ Tomás Ó hAilín, 'Irish Revival Movements' in Brian Ó Cuív, A View of the Irish Language, pg. 94.

- ^ "Archbishop John McHale", Mayo Historical and Archaeological Society, 29, May 2005

- ^ a b c O'Reilly, Bernard. John MacHale, Archbishop of Tuam, Vol.1, Fr. Pustet & Co., New York, 1890

- ^ a b c Hamrock, Ivor. Most Rev Dr John MacHale, Archbishop of Tuam", Leabharlann Chontae Mhaaigh Eo Archived 4 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b The Illustrated Catholic family annual for the United States, for the year of our Lord 1884. New York: The Catholic Publication Society. 1884. pp. 32–37.

- ^ Moore 1893.

- ^ a b "John MacHale, Archbishop (1791-1881)", Ricorso.net. Accessed 3 October 2022.

- ^ Burke, Oliver Joseph. The History of the Catholic Archbishops of Tuam, Dublin, 1882

- ^ British Library Catalogue entry

- ^ British Library Catalogue entry

- ^ a b Lernout, Geert (2010). Help My Unbelief: James Joyce and Religion. London: Continuum. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4411-9474-9.

- ^ O'Reilly 1890 vol.2 pp.546–7

- ^ Axel Klein: "McSwiney, Paul", in: Ireland and the Americas. Culture, Politics, and History, ed. by James P. Byrne, Philip Coleman, Jason King (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 2008), pp. 584–585.

- ^ Western People – 2004/09/08: It’s all change on McHale Road Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

References[edit]

- Andrews, Hilary (2001). The Lion of the West. Veritas. ISBN 978-1-85390-572-8.

- Collins, Kevin (2008). Catholic Churchmen and the Celtic Revival in Ireland, 1848–1916. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1851826582.

- Moore, Norman (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- O'Reilly, Bernard (1890). John MacHale, Archbishop of Tuam: His Life, Times and Correspondence. New York: Fr. Pustet. Vol.I Vol.II

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "John MacHale". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "John MacHale". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Machale, John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links[edit]

- 1791 births

- 1881 deaths

- 19th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in Ireland

- Alumni of St Patrick's College, Maynooth

- Deaths from pneumonia in the Republic of Ireland

- Irish writers

- People from Castlebar

- Christian clergy from County Mayo

- Roman Catholic archbishops of Tuam

- Roman Catholic bishops of Killala

- Roman Catholic writers

- Irish Roman Catholic archbishops