Inkatha Freedom Party

Inkatha Freedom Party IQembu leNkatha yeNkululeko (Zulu) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | IFP |

| President | Velenkosini Hlabisa[1] |

| Chairperson | MB Gwala[1] |

| Secretary-General | Siphosethu Ngcobo[1] |

| Spokesperson | Mkhuleko Hlengwa[1] |

| Deputy President | Inkosi Buthelezi[1] |

| Deputy Secretary-General | Albert Mncwango[1] |

| Treasurer-General | Narend Singh[1] |

| Deputy Chairperson | Thembeni Madlopha-Mthethwa[1] |

| Parliamentary leader | Velenkosini Hlabisa |

| Founder | Mangosuthu Buthelezi |

| Founded | 21 March 1975 |

| Headquarters | 2 Durban Club Place Durban KwaZulu-Natal |

| Student wing | South African Democratic Students Movement |

| Ideology | Conservatism Anti-communism Ubuntu philosophy Constitutional monarchism[2] Factions: KwaZulu-Natal regionalism |

| Political position | Right-wing |

| National affiliation | Multi-Party Charter |

| Continental affiliation | Democrat Union of Africa |

| International affiliation | International Democrat Union |

| Colours | Red |

| National Assembly seats | 14 / 400 |

| NCOP seats | 2 / 90 |

| Provincial Legislatures | 14 / 430 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

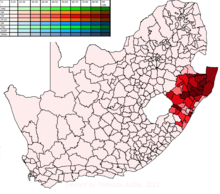

The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP; Zulu: IQembu leNkatha yeNkululeko) is a right-wing political party in South Africa. Although registered as a national party, it has had only minor electoral success outside its home province of KwaZulu-Natal. Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who served as chief minister of KwaZulu during the Apartheid period, founded the party in 1975 and led it until 2019. He was succeeded as party president in 2019 by Velenkosini Hlabisa.

During the first decade of the post-Apartheid period, the IFP received over 90% of its support from ethnic Zulus. Since then, the party has worked to increase its national support by promoting social and economic conservative policies.[3] In the 2019 general election, the IFP came in fourth place nationally, winning 3.38% of the vote and 14 seats in the National Assembly.[4]

Policies and ideology[edit]

Policy proposals of the IFP include:

- Devolution of power to provincial governments[5]

- Making the head of state and head of government posts separate, with a ceremonial figurehead as head of state.[5]

- Mixed-member proportional representation for the National Assembly.[5]

- Liberalisation of trade

- Lower income taxes[6]

- More flexible labour laws

- Autonomy for traditional African communities and their leaders

- Allowing traditional authorities to exercise local government functions

- Opposing the notion that tribalism is inherently regressive and antithetic to development and progress.

In 2018, the party issued an official statement, penned by MP, Narend Singh, stating that the time had come to discuss the possibility of reinstating the death penalty in South Africa.[7]

Ideologically, the party has been positioned on the right-wing of the spectrum although on its platform the IFP places itself in the political centre ground, stating it rejects "both centralised socialism, as well as harsh anything goes liberalism." The party states that it bases its values on Ubuntu/Botho tribal values and supports a pluralist, shared future for South Africa in which all groups have equal rights. Additionally, the party supports strong law & order policies, in particular calling for harsher penalties for people who commit violence against women and children. The IFP also supports the Zulu monarchy and investing more powers and recognition of the constitutional monarch of the KwaZulu-Natal region.[8]

History[edit]

Apartheid era[edit]

Mangosuthu Buthelezi, a former member of the ANC Youth League, founded the Inkatha National Cultural Liberation Movement (INCLM) on 21 March 1975.[9] In 1994, the name was changed to Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).[10] Buthelezi used a structure rooted in Inkatha (meaning "crown" in Zulu), a 1920s cultural organisation for Zulus established by his uncle, Zulu king Solomon kaDinuzulu.[11] The party was established in what is now KwaZulu-Natal, after which branches of the party quickly sprang up in the Transvaal, the Orange Free State and the Western Cape.

Because of Buthelezi's former position in the African National Congress, the two organisations were initially very close and each supported the other in the anti-apartheid struggle. However, by the early 1980s the Inkatha had come to be regarded as a thorn in the side of the ANC, which wielded much more political force through the United Democratic Front (UDF), than Inkatha and the Pan Africanist Congress.[12] Although the Inkatha leadership initially favoured non-violence, there is clear evidence that during the time that negotiations were taking place in the early 1990s, Inkatha and ANC members were at war with each other, and Self-Protection Units (SPUs) and Self-Defence Units (SDUs) were formed, respectively, as their protection forces.[13]

As a Homeland leader, the power of Buthelezi depended on the South African state and economy. With anti-apartheid leaders inside South Africa and abroad demanding sanctions, Buthelezi came to be regarded more and more as a government puppet, along with other Bantustan leaders. His tribal loyalties and focus on ethnic interests over national unity were also criticised as contributing to the divisive programme of Inkatha. This led to a virtual civil war between Zulu loyalist supporters and ANC members in KwaZulu-Natal.[14] Although Inkatha was allied with the African National Congress in the struggle against apartheid they took opposing views on sanctions placed by the international community on South Africa. In 1984, Buthelezi travelled to the USA and met personally with President Ronald Reagan and argued divestment was economically harming black South African workers.[15]

Fearing erosion of his power, Buthelezi collaborated with the South African Defence Force and received military training for Zulu militia from SADF special forces starting in the 1980s as part of Operation Marion. Inkatha members were involved in several massacres in the run-up to South Africa's first democratic elections, including the Trust Feed massacre on 3 December 1988, and the Boipatong massacre on 17 June 1992.[16] In November 1993, the IFP signed a solidarity pact with the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging, with the AWB providing the IFP with military training and agreeing that "Boer and Zulu would fight together for freedom and land should they be confronted by a common enemy".[17]

During the phase of establishing a constitution for South Africa and prior to the first free elections in South African history, bloodshed frequently occurred between Inkatha and the ANC. Both Inkatha and ANC attempted to campaign in each other's KwaZulu-Natal strongholds and were met with resistance, sometimes violent, by members of the opposing party. Inkatha was also initially opposed to parts of the proposed South African constitution regarding the internal politics of KwaZulu, and, in particular, they campaigned for an autonomous and sovereign Zulu king, (King Goodwill Zwelethini kaBhekuzulu), as head of state. As a result, Inkatha abstained from registering its party for the 1994 election (a necessity in order to receive votes), in opposition. However, once it became obvious that its efforts were not going to stop the election, the party was registered as the Inkatha Freedom Party at the eleventh hour. However, due to their opposition to the constitution, concessions were made and KwaZulu-Natal (and thus all the other provinces) were granted double ballots for provincial and national legislatures, greater provincial powers, the inclusion of 'KwaZulu' in the official name of the province (formerly 'Natal') and recognition of specific ethnic and tribal groups within the province.[18]

On election day, the IFP displayed its political strength by taking the majority of the votes for KwaZulu-Natal.[13]

Post-apartheid politics[edit]

After the dismantling of apartheid system in 1994, the IFP formed an uneasy coalition in the national government with their traditional political rival, the ANC. Despite these challenges, the coalition was to last until 2004, when the IFP joined the opposition benches.[19]

The ANC/IFP rivalry, characterised by sporadic acts of political violence, has been firm since 1993. In 2004, while campaigning in Vulindlela, an IFP bastion in the Pietermaritzburg Midlands region, Thabo Mbeki was reportedly debarred by an IFP-affiliated traditional leader in Mafunze. Previously the stronghold of Moses Mabhida, this area has long been the site of heated clashes between the parties.[20][full citation needed]

The IFP's manifesto seeks the resolution to a number of South African issues, especially the AIDS crisis, in addition to addressing "unemployment, crime, poverty and corruption and prevent the consolidation of a one-party state;"[21] said "party" is implied to be the ANC.

Gavin Woods report[edit]

Gavin Woods, one of the party's most respected MPs, drew up a highly critical 11-page internal discussion document[22] at the request of the parliamentary caucus after a discussion in October 2004. In it, he said that the IFP "has no discernible vision, mission or philosophical base, no clear national ambitions or direction, no articulated ideological basis and offers little in the way of current, vibrant original and relevant policies". Woods also warned the party that "it must treat Buthelezi as the leader of a political party and not the political party itself". Woods pinpointed 1987 as the year when the IFP started losing ground as a political force. Before 1987, Woods contends, the party had a strong, unambiguous national identity. He further criticised the IFP's inability to end the ANC's campaign of violence against it, and an "impotent" attitude towards the attacks conducted against it by the ANC.

At the first caucus discussion, Woods read out the 11-page paper in full and caucus members were generally positive about its frank nature. IFP president Mangosuthu Buthelezi was absent from that meeting but raised it at a meeting of the party's national council, which Woods did not attend. At a subsequent caucus meeting where both were present, Buthelezi read from a prepared statement attacking Woods. All the numbered copies were ordered to be "shredded" but some survived.[23]

Electoral decline[edit]

After the 1994 elections, the IFP suffered a gradual decline in support. The party ceded control of the KwaZulu-Natal province to the ANC following the 2004 general election and its presence in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, its stronghold, started to become diminished.[24] Party member Ziba Jiyane left the IFP to form the National Democratic Convention (Nadeco). Prominent IFP MP Gavin Woods and IFP ward councillors in KwaZulu-Natal joined his new party.[25][26]

After the party's results in the 2009 general elections, party members began debating a change in leadership for the 2011 local government elections. Buthelezi had previously announced his retirement but rescinded it. Senior IFP politician Zanele kaMagwaza-Msibi wanted Buthelezi to step down and had supporters advocating for her to take over the party's leadership.[27] She later resigned from the party and formed a breakaway party, the National Freedom Party (NFP).[28] The NFP obtained 2.4% of the national vote and 10.4% in KwaZulu-Natal in the 2011 municipal elections, mainly at the expense of the IFP.[29][30]

In the 2014 general elections, the party achieved its lowest support levels since 1994. The party lost its status as the official opposition in the KwaZulu-Natal Legislature to the Democratic Alliance. Nationally, the party lost eight seats in the National Assembly. The NFP factor also contributed to the IFP's decline on the national and provincial level.[31]

Buthelezi later said in 2019 that the reason the party had lost support, was because of ANC president Jacob Zuma being from the Zulu tribe. He insisted that the exodus voters leaving the IFP occurred on ethnic grounds.[32]

Resurgence and succession[edit]

In the 2016 municipal elections, the party's support grew for the first time since 1994. The party had reclaimed support in Northern KwaZulu-Natal. The ANC and DA both suggested that the NFP not being able to participate in the election, contributed to the party's surge in support.[33] The party managed to retain control of the Nkandla Local Municipality, the residence of former ANC president Jacob Zuma.[34]

In October 2017, Buthelezi announced that he would step down as leader of the IFP at the party's National General Conference in 2019. The party's Extended National Council pledged its support to Velenkosini Hlabisa, mayor of the Big Five Hlabisa Local Municipality, to succeed Buthelezi as party leader.[35] The party grew its support in the May 2019 general elections and won back the title of official opposition in KwaZulu-Natal.[36] Hlabisa became the leader of the opposition in the legislature, as he was the party's premier candidate. Buthelezi confirmed his intention to stand down as leader.[37] Hlabisa was elected president of the IFP at the party's 35th National General Conference in August 2019.[38]

Election results[edit]

National elections[edit]

| Election | Total votes | Share of vote | Seats | +/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 2,058,294 | 10.54% | 43 / 400

|

– | Government of National Unity |

| 1999 | 1,371,477 | 8.58% | 34 / 400

|

First Cabinet of Thabo Mbeki | |

| 2004 | 1,088,664 | 6.97% | 28 / 400

|

in opposition | |

| 2009 | 804,260 | 4.55% | 18 / 400

|

in opposition | |

| 2014[39] | 441,854 | 2.40% | 10 / 400

|

in opposition | |

| 2019 | 588,839 | 3.38% | 14 / 400

|

in opposition |

Provincial elections[edit]

| Election[39][40] | Eastern Cape | Free State | Gauteng | Kwazulu-Natal | Limpopo | Mpumalanga | North-West | Northern Cape | Western Cape | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | |

| 1994 | 0.17% | 0/56 | 0.51% | 0/30 | 3.66% | 3/86 | 50.32% | 41/81 | 0.12% | 0/40 | 1.52% | 0/30 | 0.38% | 0/30 | 0.42% | 0/30 | 0.35% | 0/42 |

| 1999 | 0.33% | 0/63 | 0.47% | 0/30 | 3.51% | 3/73 | 41.90% | 34/80 | 0.34% | 0/49 | 1.41% | 0/30 | 0.52% | 0/33 | 0.53% | 0/30 | 0.18% | 0/42 |

| 2004 | 0.20% | 0/63 | 0.35% | 0/30 | 2.51% | 2/73 | 36.82% | 30/80 | — | — | 0.96% | 0/30 | 0.25% | 0/33 | 0.24% | 0/30 | 0.14% | 0/42 |

| 2009 | 0.10% | 0/63 | 0.22% | 0/30 | 1.49% | 1/73 | 22.40% | 18/80 | 0.06% | 0/49 | 0.50% | 0/30 | 0.15% | 0/33 | 0.19% | 0/30 | 0.06% | 0/42 |

| 2014 | 0.06% | 0/63 | 0.11% | 0/30 | 0.78% | 1/73 | 10.86% | 9/80 | 0.08% | 0/49 | 0.26% | 0/30 | 0.14% | 0/33 | 0.06% | 0/30 | 0.05% | 0/42 |

| 2019 | 0.05% | 0/63 | 0.08% | 0/30 | 0.89% | 1/73 | 16.34% | 13/80 | 0.05% | 0/49 | 0.31% | 0/30 | 0.08% | 0/33 | - | - | 0.03% | 0/42 |

KwaZulu-Natal provincial elections[edit]

| Election | Votes | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 1,844,070 | 50.32 | 41 |

| 1999 | 1,241,522 | 41.90 | 34 |

| 2004 | 1,009,267 | 36.82 | 30 |

| 2009 | 780,027 | 22.40 | 18 |

| 2014[39] | 416,496 | 10.86 | 9 |

| 2019 | 588,046 | 16.34 | 13 |

Municipal elections[edit]

| Election | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1995–96 | 757,704 | 8.7% |

| 2000 | 9.1% | |

| 2006 | 2,120,142 | 8.1% |

| 2011 | 954,021 | 3.6% |

| 2016[41] | 1,823,382 | 4.7% |

| 2021[42] | 1,916,170 | 6.3% |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Duma, Nkosikhona (25 August 2019). "The IFP's new top six revealed". EWN. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Article 60" (PDF). Constitution of Kwazulu-Natal. 2015. (proposed)

- ^ Piombo, Jessica (2009), Piombo, Jessica (ed.), "The Inkatha Freedom Party: Turning away from Ethnic Power", Institutions, Ethnicity, and Political Mobilization in South Africa, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 143–162, doi:10.1057/9780230623828_8, ISBN 978-0-230-62382-8, retrieved 16 June 2023

- ^ "South Africa's ANC wins vote, loses seats; 14 parties secure seats (Final results)". Africanews. 12 May 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Constitutional Affairs Policy". Inkatha Freedom Party. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ "Economy Policy". Inkatha Freedom Party. 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ "Should SA bring back the death penalty? IFP believes it may be time". 23 July 2018. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Our Vision". Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Inkatha Freedom Party is formed". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Lynd, Hilary (7 August 2019). "Secret details of the land deal that brought the IFP into the 94 poll". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Myeni, DN. "The KwaZulu-government and Inkatha Freedom Party's record on civil liberties in South Africa" (PDF). uzspace.unizulu.ac.za/. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Adam, Heribert; Moodley, Kogila (1992). "The Journal of Modern African Studies". 2. 30 (3): 485–510. JSTOR 161169.

- ^ a b Carver, Richard. "Kwazulu-Natal - Continued Violence and Displacement". refworld.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Southall, Roger (October 1981). "African Affairs". 321. 80 (321): 453–481. JSTOR 721987.

- ^ "Our History". Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Zuma and Zulu nationalism: A response to Gumede" Archived 21 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. pambazuka.org

- ^ SPIN. September 1994. pp. 92, 96. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "The day apartheid died: Bombs and chaos no bar to voters". The Guardian. 27 April 1994. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Khan, Farook (19 April 2004). "Indian voters helped ANC win KZN". IOL. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Olifant and Khumalo 2009.

- ^ "IFP official website". Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2004.

- ^ "IFP has 'no mission, no vision'". Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Buthelezi makes blood boil". News24 Archives. Johannesburg. 15 August 2005. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "The IFP is on the verge of being extinct". SowetanLIVE. 19 May 2009. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Quintal, Angela (7 September 2005). "Gavin Woods leaves IFP for new party". IOL. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Madlala, Bheko (20 September 2005). "Jiyane bounces back". IOL. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Mgaga, Thando (11 November 2009). "Chairwoman for president, says IFP youth". The Witness. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Mthembu, Bongani (25 January 2011). "IFP breakaway party launched". News24 Archives. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "ANC, NFP team up in KwaZulu-Natal". Mail & Guardian. 30 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "NFP wants to govern KZN". News24 Archives. 30 January 2011. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "KZN: IFP loses position as official opposition". Mail & Guardian. 9 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Modjadji, Ngwako. "Buthelezi: IFP lost support because of Zuma". CityPress - News24. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Waterworth, Tanya (5 August 2016). "NFP's absence helped IFP grow support: ANC". IOL. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Nkandla is ours: IFP". eNCA. Pretoria. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Mthethwa, Bongani (29 October 2017). "IFP leader Buthelezi calls it quits". TimesLIVE. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Saba, Athandiwe (10 May 2019). "Inkatha Freedom Party arrests the decline". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Zulu, Makhosandile (5 April 2020). "Buthelezi will not stand for re-election as IFP leader". The Citizen. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Velenkosini Hlabisa elected IFP's new president". SABC News. 25 August 2019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "2014 National and Provincial Elections Results - 2014 National and Provincial Election Results". IEC. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Results Dashboard". www.elections.org.za. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Results Summary - All Ballots" (PDF). elections.org.za. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Results Summary - All Ballots" (PDF). elections.org.za. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Google. "kaMagwaza-Msibi Gamalakhe". Google Search. 3 May 2009. (Accessed 3 May 2009.)

- Inkatha Freedom Party. "ANC Members Attack IFP Premier Candidate in Port Shepstone". Durban: IFP Press Statement, 8 April 2009.

- IFP. "ANC Members Attack IFP Premier Candidate in Port Shepstone".[permanent dead link] Inkatha Freedom Party. 8 April 2009. (Accessed 3 May 2009.)

- IFP. "ANC Members Attack IFP Premier Candidate in Port Shepstone" media.co.za. 9 April 2009. (Accessed 3 May 2009.)

- IFP. "IFP: Statement by the Inkatha Freedom Party on the attack of its Premier candidate in Port Shepstone (08/04/2009)" Polity. 8 April 2009. (Accessed 3 May 2009.)

- IFP. "IEC must reconsider ANC's eligibility for 2009 elections – IFP". Politicsweb. 24 February 2009. (Accessed 3 May 2009.)

- IFP. "IFP Calls for Forensic Audit into uMhlabuyalingana Municipality". Durban: IFP Press Statement, 9 April 2009.

- IFP. "IFP National Chair to Hold More Post-Election Rallies". Durban: IFP Press Statement, 3 May 2009.

- IFP. "IFP to Outline Plans for First 100 Days in Power in KZN". Durban: IFP Press Statement, 13 April 2009.

- Mandela, Nelson; Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela; Little Brown & Co; ISBN 0-316-54818-9 (paperback, 1995).

- Mbuyazi, Nondumiso. "IFP accuses ANC members of assault". IOL. 8 April 2009. (Accessed 3 May 2009.)

- Skosana, Ben. "SADC Must Reach Inclusive, Sustainable Solution for Zim". Durban: Inkatha Freedom Party, 26 January 2009.

- Zapiro. "Zapiro's A–Z of Election '09". Mail & Guardian. 26 April 2009. (Accessed 3 May 2009.)

External links[edit]

- Flag of the Inkatha Freedom Party

- Inkatha Freedom Party official site

- Speech by Mangosuthu Buthelezi to The Heritage Foundation, 19 June 1991.