David Copperfield (illusionist)

David Copperfield | |

|---|---|

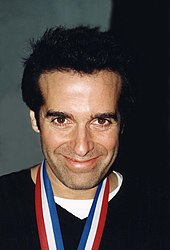

Copperfield in 2010 | |

| Born | David Seth Kotkin September 16, 1956 Metuchen, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Occupation | Magician |

| Years active | 1972–present |

| Partner(s) | Claudia Schiffer (1994–1999) Chloé Gosselin (2006–present)[1] |

| Children | 3 |

| Website | www |

David Seth Kotkin (born September 16, 1956), known professionally as David Copperfield, is an American magician, described by Forbes as the most commercially successful magician in history.[2]

Copperfield's television specials have been nominated for 38 Emmy Awards, winning 21. Best known for his combination of storytelling and illusion, his career of over 40 years has earned him 11 Guinness World Records,[3] a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame,[4] and a knighthood by the French government.[5] He has been named a Living Legend by the US Library of Congress.[6]

His illusions have included the disappearance of a Learjet (1981), the vanishing and reappearance of the Statue of Liberty (1983), levitating over the Grand Canyon (1984), walking through the Great Wall of China (1986), escaping from Alcatraz prison (1987), the disappearance of an Orient Express dining car (1991) and flying on stage for several minutes (1992).

As of 2006, he has sold 33 million tickets and grossed over US$4 billion, more than any other solo entertainer in history by a large margin.[2][3][7] In 2015, Forbes listed his earnings at $63 million for the previous 12 months and ranked him the 20th highest-earning celebrity in the world.[8]

When not performing, he manages his chain of 11 resort islands in The Bahamas, which he calls Musha Cay and the Islands of Copperfield Bay.[9]

Early life and education[edit]

Copperfield was born David Seth Kotkin in Metuchen, New Jersey,[10][11] the son of Jewish parents Rebecca Kotkin (née Gispan; 1924–2008), an insurance adjuster, and Hyman Kotkin (1922–2006), who owned and operated Korby's, a men's haberdashery in Warren, New Jersey.[10] His mother was born in Jerusalem, while his paternal grandparents were Jewish emigrants from the Ukrainian SSR (present-day Ukraine).[12][13] In 1974 he graduated from Metuchen High School.[14]

Copperfield started his career as a ventriloquist at the age of 8 with his own 'Jerry Mahoney' puppet.[15][16] When he was 10, he began practicing magic as "Davino the Boy Magician" in his neighborhood,[17] and at age 12, he became the youngest person admitted to the Society of American Magicians.[18] Shy and a loner, the young Copperfield saw magic as a way to fit in and, later, to meet women.[19] As a child, he attended Camp Harmony, a day camp in nearby Warren, New Jersey, where he began practicing magic and ventriloquism, an experience to which he credits his creative style. He said, "At Camp Harmony, we spent two weeks searching for a guide who'd been kidnapped by Indians. It was just a game, but I was living it. My whole life goes back to that camp experience when I was three or four."[20] As a teenager, he became fascinated with Broadway and frequently sneaked into shows, especially musicals featuring the work of Stephen Sondheim or Bob Fosse.[21] By age 16, he was teaching a course in magic at New York University.[22]

Career and business interests[edit]

At 18, Copperfield enrolled at New York City's Jesuit-based Fordham University, but three weeks into his freshman year he left to play the lead role in the musical The Magic Man in Chicago. It was then he adopted the stage name David Copperfield, taken from the famous Charles Dickens novel, because he liked its sound. He sang, danced and created most of the original illusions used in the show. The Magic Man became the longest-running musical in Chicago history.[23][24]

At age 19, he created and headlined for several months the first "Magic of David Copperfield" show at the Pagoda Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii, with the help of sound and lighting designer Willy Martin.[25]

Copperfield's career in television began in earnest when he was discovered by Joseph Cates, a producer of Broadway shows and television specials.[26] Cates produced a magic special in 1977 for ABC called The Magic of ABC, hosted by Copperfield,[27] as well as several The Magic of David Copperfield specials on CBS between 1978 and 2001.[26] There have been 18 Copperfield TV specials and 2 documentaries between September 7, 1977, and April 3, 2001.

Copperfield also played the character The Magician in the 1980 horror film Terror Train and had an uncredited appearance in the 1994 film Prêt-à-Porter. Most of his media appearances have been through television specials and guest spots on television programs.

One of his most famous illusions occurred on television on April 8, 1983: A live audience of 20 tourists was seated in front of a giant curtain attached to two lateral scaffoldings built on Liberty Island in an enclosed viewing area. Copperfield, with help from Jim Steinmeyer[28] and Don Wayne, raised the curtain before lowering it again a few seconds later to reveal that the space where the Statue of Liberty once stood was empty. A helicopter hovered overhead to give an aerial view of the illusion and the statue appeared to have vanished, with only the circle of lights surrounding it still present and visible. Before making the statue reappear, Copperfield explained in front of the camera why he wanted to perform this illusion. He wanted people to imagine what it would be like if there were no liberty or freedom in the world today and what the world would be like without the freedoms and rights we enjoy. Copperfield then brought the statue back, ending the illusion by saying that "our ancestors couldn't (enjoy rights and freedoms), we can and our children will". Both the disappearance and the reappearance of the statue were filmed in long take to demonstrate the absence of camera tricks.[29][30] This illusion was featured in season four of The Americans, in an episode entitled “The Magic of David Copperfield V: The Statue of Liberty Disappears,” and in the 2019 HBO documentary Liberty: Mother of Exiles.[31][32]

In 1986, Copperfield debuted a new variation on the classic sawing a woman in half illusion. Copperfield’s Death Saw illusion was presented as an escape gone wrong, sawing himself, rather than an assistant, in half with a large rotary saw blade which descended from above.[33] Copperfield’s Death Saw has become one of his most well-known illusions.[34][35]

In 1996, in collaboration with Francis Ford Coppola, David Ives, and Eiko Ishioka, Copperfield's Broadway show Dreams & Nightmares broke box office records in New York at the Martin Beck Theatre.[36] Reviewer Greg Evans described the sold-out show in Variety magazine: "With a likable, self-effacing demeanor that rarely comes across in his TV specials, Copperfield leads the audience through nearly two hours of truly mind-boggling illusions. He disappears and reappears, gets cut in half, makes audience members vanish and others levitate. Copperfield climaxes his show with a flying routine, seven years in the making, that defies both logic and visual evidence, he could probably retire just by selling his secrets to future productions of Peter Pan".[37]

Also in 1996, Copperfield joined forces with Dean Koontz, Joyce Carol Oates, Ray Bradbury and others for David Copperfield's Tales of the Impossible, an anthology of original fiction set in the world of magic and illusion. A second volume, David Copperfield's Beyond Imagination, was published in 1997. In addition to the two books, Copperfield wrote an essay as part of NPR's "This I Believe" series and This I Believe, Inc.[38]

In May 2001, Copperfield entertained guests at a White House benefit for UNICEF by performing a new illusion in which he sawed singer and actress Jennifer Lopez into six pieces while standing up.[39] This illusion was an update of one he performed in one of his early TV specials on actress Catherine Bach, and has never been performed publicly in any of his stage or TV appearances.

In 2002, he was the subject of an hour-long biographical special on A&E's "Biography" channel.

On April 5, 2009, Copperfield made his first live TV appearance for some time when he entertained the audience at the 44th Annual Academy of Country Music Awards with two illusions. First, he made singer Taylor Swift appear inside an apparently empty translucent-sided elevator as it was lowered from the ceiling; he then sawed her in half in his Clearly Impossible illusion.[40]

On May 7, 2009, Copperfield was dropped by Michael Jackson from Jackson's residency at the O2 Arena after a disagreement over money. Copperfield wanted $1 million (£666,000) per show.[41] Copperfield denied the reports of a falling-out, saying "don't believe everything you read."[42] News of Copperfield's collaboration with Jackson first surfaced on April 1, 2009, and has since been described as a possible April Fool's prank.[43][44]

In July 2009, he filmed a number of scenes for a cameo appearance in episode 8 of the short-lived TV drama The Beautiful Life. In these scenes, he worked alongside actresses Mischa Barton and Sara Paxton performing a number of illusions including a sawing in half of Barton's character Sonja Stone in a specially-developed box-less version of the illusion.[45][46] Due to the show's cancellation after just two episodes had been aired, episode 8 was never completed and the footage of Copperfield's performances remains unseen.

In August 2009, Copperfield took his show to Australia.[47][48]

In January 2011 Copperfield joined the cast of the feature film Burt Wonderstone with Steve Carell, Jim Carrey, James Gandolfini and Olivia Wilde. Copperfield and his team developed illusions used in the film.[49] He also coached Carell and Wilde on how to perform the 'Impossible Sawing' illusion, in which Wilde's character is sawed in half and her halves separated without the use of any covering or camera tricks. Copperfield has served as technical advisor on several other films, including The Prestige and Now You See Me.[50] He also served as a co-producer of the film Now You See Me 2.[51]

In July 2012, OWN-TV network aired a one-hour special and interview with Copperfield as part of the network's Oprah's Next Chapter series. The show featured many aspects of Copperfield's personal life and family—with tours of his island home and Las Vegas conjuring museum—and a sampling of his illusions and magic effects. During the interview, he and his girlfriend Chloé Gosselin, a French fashion model, announced their engagement and appeared together briefly with their young daughter, strolling down the beach on the island.[52]

In 2018, the New York Historical Society hosted “Summer of Magic: Treasures from the David Copperfield Collection.”[53] The exhibit recounted the history of magic in New York and displayed some of Copperfield’s most popular illusions, like the Death Saw, and historical magical ephemera, including some of Copperfield’s collection of Houdini memorabilia.[34][54]

Copperfield made the missing star from the original Star-Spangled Banner flag reappear in an illusion on Flag Day 2019, in partnership with Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. The missing star, which is believed to have been removed in the nineteenth century, reappeared inside a box that seemed to levitate.[55][56]

Copperfield notes that his role models were not magicians, that "My idols were Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire and Orson Welles and Walt Disney ... they took their individual art forms and they moved people with them... I wanted to do the same thing with magic. I wanted to take magic and make it romantic and make it sexy and make it funny and make it goofy ... all the different things that a songwriter gets to express or a filmmaker gets to express".[57] This approach, despite its obvious popularity with audiences, has its share of detractors within the profession. One magician has described Copperfield's stage presentations as "resembling entertainment the way Velveeta resembles cheese".[58]

International Museum and Library of the Conjuring Arts[edit]

Copperfield owns the International Museum and Library of the Conjuring Arts, which houses the world's largest[59] collection of historically significant magic memorabilia, books and artifacts. Begun in 1991 when Copperfield purchased the Mulholland Library of Conjuring and the Allied Arts, which contained the world's largest collection of Houdini memorabilia,[2] the museum comprises approximately 80,000 items, including Houdini's Water Torture Cabinet and Metamorphosis Trunk, Orson Welles' Buzz Saw illusion, and automata created by Robert-Houdin.[59][60][61] Copperfield's 1991 Mulholland purchase, which formed the core of his collection, engendered criticism from some magicians. One told a reporter, "David Copperfield buying the Mulholland Library is like an Elvis impersonator winding up with Graceland."[58] In 1992, Copperfield agreed to purchase the largest private magic collection in the world from Dr. Robert Albo to add to the museum.[62] It houses the world's largest collection of "Houdiniana" (the second largest being Houdini Museum of New York).[63][64][65]

The museum is not open to the public; tours are reserved for "colleagues, fellow magicians, and serious collectors".[59] Located in a warehouse at Copperfield's headquarters in Las Vegas, the museum is entered via a secret door in what described by Forbes as a "mail-order lingerie warehouse".[2] "It doesn't need to be secret, it needs to be respected", Copperfield said. "If a scholar or journalist needs a piece of magic history, it's there."[61][27][66]

Musha Cay and the Islands of Copperfield Bay[edit]

In 2006, Copperfield bought eleven Bahamian islands called Musha Cay.[67] Renamed "The Islands of Copperfield Bay",[67] the islands are a private resort.[68] Guests have reportedly included Oprah Winfrey and John Travolta. Google co-founder Sergey Brin was married there.[69] Copperfield has said that the islands may contain the Fountain of Youth, a claim that resulted in him receiving a Dubious Achievement Award from Esquire magazine in 2006.[70]

"Magic Underground" restaurant[edit]

David Copperfield's Magic Underground was planned to be a restaurant based on Copperfield's magic.[71] At Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida, a sign on Hollywood Boulevard during the late 1990s indicated the restaurant was coming soon. Signs also appeared around Pleasure Island and outside Disney-MGM Studios.[72] A Magic Underground restaurant was also to open in New York's Times Square.[71] Plans included eventual expansion into Disneyland in Anaheim, California, as well as Paris and Tokyo.[73] The restaurants were to have magic props and other items on the walls; magicians would go around to tables doing sleight of hand tricks. There was also to be a larger stage for larger stunts.[74][self-published source?] The restaurant in Times Square was 85% completed,[73] but amid disputes between the creative team and the financial team and enormous cost overruns, finances dried up from the investors, the project was canceled, and Disney canceled the lease.[75] Copperfield was not an investor in the project; the investors reportedly lost $34 million, and subcontractors placed $15 million in liens.[73][76]

Recorded message for expanded gambling in Maryland[edit]

In October 2012, Maryland residents received a robocall from Copperfield supporting a ballot initiative that would expand gambling in the state.[77]

Copperfield's Secrets on the Moon[edit]

Copperfield's magic secrets and related technological innovations are etched into nickel plates, designed to last billions of years, as part of the Arch Mission Foundation "lunar library" that crashed into the moon in April 2019 during an attempted landing of the lunar module Beresheet. It is believed the payload survived.[78][79][80]

Accidents and injuries[edit]

On March 11, 1984, while rehearsing an illusion called "Escape From Death" where he was shackled and handcuffed in a tank of water, Copperfield became tangled in the chains and started taking in water and banging into the sides of the tank.[57] He was pulled from the water after 80 seconds, hyperventilating and in shock, taken to a Burbank hospital, and found to have pulled tendons in arms and legs. He was in a wheelchair for a week and used a cane for a period thereafter.[81]

While doing a rope trick at a show in Memphis in 1989, Copperfield accidentally cut off the tip of his finger with sharp scissors.[82] He was rushed to the hospital and the fingertip was reattached.[83]

On December 17, 2008, during a live performance in Las Vegas, a 26-year-old assistant named Brandon was sucked into the spinning blades of a 12 feet (3.7 m) high industrial fan that Copperfield walks through. The assistant sustained multiple fractures to his arm, severe bleeding, and facial lacerations that required stitches.[84] Copperfield canceled the rest of the performance and offered the audience members refunds.

Magic as an art form[edit]

Since 2016, Copperfield has campaigned for Congressional Resolution 642, which would “recognize magic as a rare and valuable art form and national treasure".[85][86] The campaign has been unsuccessful as of November 2022.

Las Vegas residency[edit]

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Copperfield was performing daily, with 15 shows scheduled each week, at the David Copperfield theater in the MGM Grand Las Vegas. Each show was 90 minutes in duration.[87][88]

Litigation[edit]

On July 11, 1994, Copperfield sued magician and author Herbert L. Becker in order to prevent publication of Becker's book which reveals how magicians perform their illusions.[89] Becker won the lawsuit[90] but, because of a secrecy agreement Becker signed with Copperfield and an independent finding that Becker's description of Copperfield's methods was inaccurate, the publisher removed the section on Copperfield from the book before publication.[91] In 1997, Becker sued Copperfield and Lifetime Books for $50 million for breach of contract between himself and Lifetime Books, the publisher of his book All the Secrets of Magic Revealed. Copperfield settled at the last moment and the publisher lost during the court trial.[92]

In 1997, Copperfield and Claudia Schiffer sued Paris Match for $30 million after the magazine claimed their relationship was a sham,[93] that Schiffer was paid for pretending to be Copperfield's fiancée and that she did not even like him.[94][95] In 1999, they won an undisclosed sum and a retraction from Paris Match.[96] Herbert L. Becker, whom Copperfield asked to testify to the validity of the relationship, did so. Copperfield's publicist confirmed that Schiffer had a contract to appear in the audience at Copperfield's show in Berlin where they met, but was not under contract to be his "consort".[97]

On August 25, 2000, Copperfield unsuccessfully sued Fireman's Fund Insurance Company for reimbursement of a $506,343 ransom paid to individuals in Russia who had commandeered the entertainer's equipment there.[98][99][100]

In 2004, John Melk, co-founder of Blockbuster Inc., and previous owner of Musha Cay, sued Copperfield for fraud after Copperfield purchased the island chain, alleging that Copperfield had deliberately obscured his identity during the purchase and that he would not have sold the island to Copperfield.[101] Copperfield claimed that Melk had agreed to sell the property to Copperfield's Imagine Nation Company, and that Copperfield negotiated the deal through a third party because he feared Melk was "seeking to exploit" Copperfield's celebrity status by demanding an unfair price.[102] The case was settled in 2006, after mutual friend, Herbert L. Becker was brought in by both parties to negotiate a settlement. The terms of the settlement are undisclosed.[101]

On November 6, 2007, Viva Art International Ltd and Maz Concerts Inc. sued Copperfield for nearly $2.2 million for breach of contract[103][104] and the Indonesian promoter of Copperfield's canceled shows in Jakarta held on to $550,000 worth of Copperfield's equipment in lieu of money paid to Copperfield that had not been returned.[105] Copperfield countersued, and the dispute was resolved in July 2009.[106]

In 2018, a lawsuit alleging that a British tourist and audience member Gavin Cox was injured during a November 2013 performance, was resolved in Copperfield's favor. He was found "not liable".[107]

Sexual assault allegations[edit]

Copperfield was accused of sexual assault in 2007 by Lacey L. Carroll.[108] A federal grand jury in Seattle closed the investigation in January 2010 without bringing charges.[109][110] In January 2010, the Bellevue City Prosecutor's Office brought misdemeanor charges against Carroll for prostitution and allegedly making a false accusation of rape in another case.[111] Carroll filed a civil lawsuit against Copperfield,[112] which was dropped in April 2010.[113][114] In January 2018, Copperfield was accused of drugging and assaulting a teenager in 1988.[115] Copperfield published a statement in response on January 24, 2018.[116] In 2024, Copperfield's name was listed as one of the associates of American financier and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.[117]

Personal life[edit]

In 1993 at a Berlin celebrity gala Copperfield met German supermodel Claudia Schiffer when he brought her on stage to participate in a mind-reading act and his flying illusion, and in January 1994 they became engaged. During the engagement, Schiffer sometimes appeared on stage with Copperfield to act as his special guest assistant in illusions including being sawn in half.[118][119][120] She also appeared alongside Copperfield in David Copperfield: 15 Years of Magic (1994), a documentary in which she played the role of a reporter interviewing him, and at the end of which they reprised their performance of the "Flying" illusion. After a nearly six-year engagement, in September 1999 they announced their separation, citing work schedules.[121]

In April 2006, he and two female assistants were robbed at gunpoint after a performance in West Palm Beach, Florida.[122] His assistants handed over their money, passports, and a cell phone. According to his police statement, Copperfield did not hand over anything, claiming that he used sleight of hand to hide his possessions,[123] although later admitting that doing so was "a reflex that could have got me shot."[124] One of the assistants wrote down most of the license plate number, and the suspects were later arrested, charged, and sentenced.[125]

Copperfield's girlfriend Chloé Gosselin, a French fashion model 28 years his junior, gave birth to his daughter in 2010. Copperfield has two other children, a son and a daughter.[126]

In July 2016, Copperfield purchased a mansion at 1625 Enclave Court in Las Vegas's affluent Summerlin community for $17.55 million.[127]

Earnings[edit]

| David Copperfield on the Forbes Celebrity 100 List[128] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year (June–June) | Pay (USD, millions) | Power rank | Pay rank |

| 1999–2000 | not on list | ||

| 2001 | 60 | 23 | 5 |

| 2002 | not on list | ||

| 2003 | 55 | 43 | 10 |

| 2004 | 57 | 35 | 10 |

| 2005 | 57 | 41 | 10 |

| 2006–2008 | not on list | ||

| 2009 | 30 | 80 | 50 |

Forbes magazine reported that Copperfield earned $55 million in 2003, making him the 10th highest paid celebrity in the world (earnings figures are pre-tax and before deductions for agents' and attorneys' fees, etc.).[129] He earned $57 million in 2004 and 2005, and $30 million in 2009 in entertainment earnings, according to Forbes.[130][131] Copperfield performs over 500 shows per year throughout the world.[132]

Charitable activities[edit]

In March 1982, Copperfield founded Project Magic,[133] a rehabilitation program to help disabled patients regain lost or damaged dexterity skills by using sleight of hand as physical therapy.[133] The program has been accredited by the American Occupational Therapy Association, and is in use in over 1,100 hospitals in 30 countries. Copperfield made an appearance on Oprah Radio in April 2008 to talk with host Dr. Mehmet Oz about how magic can help disabled people.[134]

In 2007, he organized and performed at a charity show for UNICEF in Los Angeles, along with a number of celebrity guests. During the show, he used his ex-Orson Welles Buzz Saw illusion to saw British TV presenter Cat Deeley in half.[135]

Copperfield organized relief efforts after Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas in 2019, using his own plane to fly in supplies.[136][137]

Achievements and awards[edit]

- The Society of American Magicians named him "Magician of the Century" and the "King of Magic".[138][139]

- Copperfield has been nominated 38 times for Emmy Awards, with 21 wins.[140]

- Copperfield received a Living Legend Award from the Library of Congress.[6]

- Copperfield is the first living magician to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[4]

- Copperfield received the Chevalier of Arts and Letters, the first one ever awarded to a magician.[141]

- Copperfield was named "Magician of the Year" in 1979 and 1986 by the Academy of Magical Arts.[142]

- Forbes's "The Celebrity 100" for 2009 ranks Copperfield as the 80th most powerful celebrity, with earnings of $30 million.[130]

- Copperfield was inducted into New York City's Ride of Fame on September 11, 2015.[143]

- In December 2020, Copperfield became the 23rd member of the Hall of Fame of the National Museum of American Jewish History, joining Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Steven Spielberg. Copperfield inducted Harry Houdini as the 22nd member during the same ceremony.[144][145]

Guinness World Records[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Copperfield holds 11 Guinness World Records,[3][146] including:

- Most magic shows performed in a year

- Most tickets sold worldwide by a solo entertainer

- Highest career earnings as a magician

- Largest international television audience for a magician

- Highest annual earnings for a magician (current year)

- Largest Broadway attendance in a week

- Largest magic work archive

- Most expensive poster depicting magic sold at auction

- Largest illusion ever staged

Television specials[edit]

- The Magic of ABC (September 7, 1977) (with special guests Fred Berry, Shaun Cassidy, Howard Cosell, Kate Jackson, Hal Linden, Penny Marshall, Kristy McNichol, Donny Osmond, Marie Osmond, Parker Stevenson, Dick Van Patten, Adam Rich, Abe Vigoda and Cindy Williams)

- The Magic of David Copperfield (October 27, 1978) (with special guests Orson Welles, Carl Ballantine, Valerie Bertinelli, Sherman Hemsley, Bernadette Peters and Cindy Williams)

- One Emmy nomination: Outstanding Achievement in Technical Direction and Electronic Camerawork

- The Magic of David Copperfield II (October 24, 1979) (with special guest Bill Bixby, Loni Anderson, Valerie Bertinelli, Robert Stack and Alan Alan)

- One Emmy nomination: Outstanding Achievement in Technical Direction and Electronic Camerawork

- The Magic of David Copperfield III: Levitating Ferrari (September 25, 1980) (with special guest Jack Klugman, Debby Boone, Mary Crosby, Louis Nye, Shimada, Cindy Williams and David Mendenhall).

- Two Emmy nominations: Outstanding Achievement in Music Direction; Outstanding Achievement in Technical Direction and Electronic Camerawork

- The Magic of David Copperfield IV: The Vanishing Airplane (October 26, 1981) (with special guest Jason Robards, Susan Anton, Audrey Landers, Catherine Bach, David Mendenhall, Barnard Hughes, Clark Brandon and Elaine Joyce) The last illusion, Lear Jet Vanish, was filmed in long take at the Van Nuys Airport in Los Angeles, California.

- One Emmy win: Outstanding Technical Direction and Electronic Camerawork

- The Magic of David Copperfield V: The Statue of Liberty Disappears (April 8, 1983) (with special guests Morgan Fairchild, Michele Lee, Eugene Levy, William B. Williams and Lynne Griffin)

- The Magic of David Copperfield VI: Floating Over the Grand Canyon (April 6, 1984) (with special guests Ricardo Montalbán, Bonnie Tyler and Heather Thomas). The extended international version featured an additional 10 minutes of performance, including Tyler being sawed in half by Copperfield.

- One Emmy win: Outstanding Technical Direction/Camerawork/Video for a Limited Series or a Special

- Two Emmy nominations: Outstanding Achievement in Music Direction; Outstanding Live and Tape Sound Mixing and Sound Effects for a Limited Series or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield VII: Familiares (March 8, 1985) (with special guests Angie Dickinson, Teri Copley, Omri Katz and Peggy Fleming)

- One Emmy win: Outstanding Technical Direction/Electronic Camera/Video Control for a Limited Series or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield VIII: Walking Through the Great Wall of China (March 14, 1986) (with special guest Ben Vereen) – This is the only special filmed outside the United States. At the end, Copperfield promotes a return to Egypt, which he later canceled for political reasons.[147]

- Two Emmy nominations: Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Technical Direction/Electronic Camera/Video Control for a Miniseries or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield IX: The Escape From Alcatraz (March 13, 1987) (with special guest Ann Jillian) – the television show used the soundtrack of Back to the Future, unedited and in its entirety, something for which the show was later lampooned.[148]

- Two Emmy nominations: Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Lighting Direction (Electronic) for a Miniseries or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield X: The Bermuda Triangle (March 12, 1988) (with special guest Lisa Hartman) Filmed at the Caesars Palace in Las Vegas

- Two Emmy nominations: Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Technical Direction/Electronic Camera/Video Control for a Miniseries or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield XI: Explosive Encounter (March 3, 1989) (with special guest Emma Samms) Filmed at the Orange County Performing Arts Center in Orange County, California.

- Two Emmy wins: Outstanding Costume Design for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Lighting Direction (Electronic) for a Drama Series, Variety Series, Miniseries or a Special

- Two Emmy nominations: Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Sound Mixing for a Variety or Music Series or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield XII: The Niagara Falls Challenge (March 30, 1990) (with special guest Kim Alexis and Penn & Teller) Filmed at the Orange County Performing Arts Center in Orange County, California.

- One Emmy win: Outstanding Technical Direction/Camera/Video for a Miniseries or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield XIII: Mystery On The Orient Express (April 9, 1991) (with special guest Jane Seymour) Filmed in part at the Tampa Bay Performing Arts Center in Tampa Bay, Florida and the Tillamook Air Museum in Tillamook, Oregon.

- Four Emmy wins: Outstanding Achievement in Special Visual Effects; Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Lighting Direction (Electronic) for a Drama Series, Variety Series, Miniseries or a Special; Outstanding Technical Direction/Camera/Video for a Miniseries or a Special

- One Emmy nomination: Outstanding Editing for a Miniseries or a Special – Multi-Camera Production

- The Secret of The Phantom of the Opera (1991) Filmed in the Théâtre National de l'Opéra, Paris, France.

- The Magic of David Copperfield XIV: F·L·Y·I·N·G – Live The Dream (March 31, 1992) (with special guest James Earl Jones and a special appearance by the late Orson Welles) Filmed at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida.

- Three Emmy wins: Outstanding Individual Achievement in Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Individual Achievement in Editing for a Miniseries or a Special – Multi-Camera Production; Outstanding Individual Achievement in Lighting Direction (Electronic) for a Drama Series, Variety Series, Miniseries or a Special

- The Magic of David Copperfield XV: Fires Of Passion (March 12, 1993) (with special guest Wayne Gretzky) Filmed in part at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas and the Tampa Bay Performing Arts Center in Tampa Bay, Florida.

- Three Emmy wins: Outstanding Individual Achievement in Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Individual Achievement in Editing for a Miniseries or a Special – Multi-Camera Production; Outstanding Individual Achievement in Technical Direction/Camera/Video for a Miniseries or a Special

- David Copperfield: 15 Years of Magic (May 12, 1994) (with special guest Claudia Schiffer as "The Reporter", and appearances of various guests from previous specials via archive footage, such as James Earl Jones and Joanie Spina). In the international version, in addition to reprising their "Flying" illusion, Copperfield and Schiffer also reprised the performance of the Clearly Impossible illusion from Copperfield's stage shows in which Schiffer was sawed in half inside a transparent box.

- One Emmy win: Outstanding Individual Achievement in Editing for a Miniseries or a Special – Multi-Camera Production

- The Magic of David Copperfield XVI: Unexplained Forces (May 1, 1995) – Filmed at the Tampa Bay Performing Arts Center in Tampa Bay, Florida.

- Three Emmy wins: Outstanding Individual Achievement in Editing for a Miniseries or a Special – Multi-Camera Production; Outstanding Individual Achievement in Lighting Direction (Electronic) for a Drama Series, Variety Program, Miniseries or a Special; Outstanding Technical Direction/Camera/Video for a Miniseries or a Special

- Two Emmy nominations: Outstanding Individual Achievement in Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program; Outstanding Individual Achievement in Sound Mixing for a Variety or Music Series or a Special

- David Copperfield: The Great Escapes (April 26, 2000)

- Copperfield – Tornado of Fire (April 3, 2001) (with special guests Carson Daly and, only in the international version, Whoopi Goldberg. Carson Daly was replaced by Hans Kazàn in the Dutch version and Marco Berry in the Italian version) – Filmed in January 2001 in a surrounded stage at the Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis, Tennessee, and a live (in the U.S. only) tornado stunt performed at Pier 94 in New York City, NY.[149] (North America version 60 minutes, European version 90 minutes)

- One Emmy nomination: Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program

Worldwide tours[edit]

This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (August 2022) |

- The Magic of David Copperfield: Live on Stage (1983–1986)

- The Magic of David Copperfield: Radical New Illusions (1987–1989)

- David Copperfield: Magic for the 90's (1990–1994)

- David Copperfield: Beyond Imagination (a.k.a. The Best of David Copperfield) (1995–1996)

- David Copperfield: Dreams and Nightmares (a.k.a. The Magic is Back) (1996–1998)

- David Copperfield: Journey of a Lifetime (a.k.a. U!) (1999–2000)

- David Copperfield: Unknown Dimension (a.k.a. Global Encounter) (2000–2001)

- David Copperfield: Portal (2001–2002)

- David Copperfield: An Intimate Evening of Grand Illusion (a.k.a. World of Wonders) (2003–present)

Plans for new illusions[edit]

Copperfield declared that among the new illusions he plans to create, he wants to put a woman's face on Mount Rushmore, straighten the Leaning Tower of Pisa and even vanish the moon.[150][151]

Filmography[edit]

- Terror Train (1980) as the Magician

- Mister Rogers' Neighborhood (1997) as himself

- Scrubs, episode "My Lucky Day" (2002) as himself

- Oh My God (2009) as himself[152]

- America's Got Talent (2010) as himself

- The Simpsons, episode "The Great Simpsina" (2011) as himself (voice)

- Wizards of Waverly Place, episode "Harperella" (2011) as himself

- Burt Wonderstone (2013) as himself

- The Amazing Race 24 (2014)

- American Restoration (2014)

- Unity (2015) as narrator[153]

- 7 Days in Hell (2015) as himself

Popular illusions[edit]

This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (August 2022) |

Created and/or performed by Copperfield:

- Laser illusion

- Portal

- Walking Through the Great Wall of China

- Death Saw

- Clearly Impossible

- Flying illusion

- Squeeze box

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Why David Copperfield Is Afraid of Marriage". Oprah.com. July 17, 2012

- ^ a b c d "Houdini in the Desert". Forbes.com. May 8, 2006

- ^ a b c Guinness World Records 2006, p. 197 ISBN 1-904994-02-4

- ^ a b "Magic Web Channel hall of fame – David Copperfield". Magic Web Channel. September 16, 1956. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ "Reappearing Act: Inside The Multimillion Dollar World Of Illusionist David Copperfield". Forbes.com. September 5, 2013

- ^ a b "Living Legends". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ "Forbes 400 Richest Americans: Ones to Watch – David Copperfield". Forbes. 2013.

- ^ "The World's Highest-Paid Celebrities van". Forbes. November 15, 2015.

- ^ David, Richard (May 6, 2011). "David Copperfield's Caribbean Island". Departures. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Peres, Daniel. "Hy about Life". Remember Hy. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ^ Witchel, Alex (November 24, 1996). "A Maestro of the Magic Arts Returns to His Roots". The New York Times. Retrieved on December 6, 2007. "David Seth Kotkin was born in Metuchen, N.J., 40 years ago; David Copperfield was born when David Kotkin turned 18, at the suggestion of the wife of a New York Post reporter. Which is why his passport reads David Kotkin, a k a David Copperfield."

- ^ Ike Hughes (2006). "David Copperfield has made a career out of dazzling people". Lansing State Journal. Retrieved on September 22, 2008. "His dad, who managed a men's clothing store, was the son of Russian immigrants. His mom was born in Jerusalem; both wanted him to go to college and into a profession."

- ^ David Copperfield Bio (Biography) Archived June 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. / Celebrity Gossip (September 16, 1956). Retrieved on February 15, 2012.

- ^ The Ultimate New Jersey High School Year Book. The Star-Ledger.

- ^ Pannell, Tim. "The Magical World Of David Copperfield". Forbes. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ DCDI Productions. "David Copperfield: 15 Years of Magic (1994)". YouTube. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ Espinoza, Galina (April 9, 2001). "A Lift Out of Life – David Copperfield". People. Archived from the original on June 2, 2009. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ "David Copperfield Milestones". Genii. Vol. 47, no. 7. July 1983. p. 455.

- ^ "The Victoria Advocate – Google News Archive Search". Retrieved September 15, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Leith Gollner, Adam. "author". Vice. Archived from the original on February 25, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ Berson, Misha (July 24, 1997). "Entertainment & the Arts | Colossal Copperfield – Magic Superstar Throws Extravaganza As Big As Keyarena". The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ "Short bio from Chicago Gigs on Copperfield". Chicago Gigs. Archived from the original on August 18, 2009. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ "The Magic of David Copperfield". Notre Dame & St Mary's Observer. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ Brennan, Morgan. "Reappearing Act: Inside The Multimillion Dollar World of Illusionist David Copperfield". Forbes. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ David Copperfield Bio from A&E

- ^ a b "Joseph Cates, 74, a Producer Of Innovative Specials for TV". New York Times. October 12, 1998. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ^ a b Witchel, Alex (November 24, 1996). "A Maestro of the Magic Arts Returns to His Roots". The New York Times. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ Biography. jimsteinmeyer.com

- ^ David Copperfield – Vanishing the Statue of Liberty. YouTube (December 1, 2010). Retrieved on 2018-02-02.

- ^ Jory, Tom (April 8, 1983) David Copperfield and the vanishing Miss Liberty. Associated Press via Kingman Daily Miner

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (May 5, 2016). "'The Americans' recap: Two Soviet sources disappear, and family life explodes". EW.com. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Aurthur, Kate (October 3, 2019). "HBO's 'Liberty: Mother of Exiles' Examines the Origins of the Nation's Famous Statue". Variety. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Marshall, Alex (January 29, 2021). "Sawing Someone in Half Never Gets Old. Even at 100". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Summer of magic: David Copperfield exhibits his collection of wonders". the Guardian. June 19, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "From Houdini to Copperfield, a Century of Jewish Magicians". Tablet Magazine. July 10, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (December 26, 1996). "Poof! Quick as smoke questions about magic just seem to disappear". New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ Evans, Greg – "David Copperfield: Dreams & Nightmares". Variety, December 5, 1996.

- ^ "Renowned Illusionist David Copperfield to Offer Personal Essay on This I Believe Segment on All Things Considered". National Public Radio.

Renowned illusionist David Copperfield discusses his father's influence and the impact of kindness in an essay for the NPR series This I Believe airing on All Things Considered, Monday, August 21.

- ^ "Diva Dissection", People, June 25, 2001

- ^ 44th Annual Academy of Country Music Awards (2009 TV Special) Trivia. IMDb.com.

- ^ "Jackson swaps Copperfield for Angel". Daily Express. May 8, 2009.

- ^ "Copperfield denies rumours". Sky News. 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ "David Copperfield Can't Make King of Pop Items Disappear". Gossip Cop. 2009.

- ^ "David Copperfield Was Never On Jackson UK Tour". Undercover.com.au. 2009. Archived from the original on August 18, 2009. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ Bryant, S. "David Copperfield To Debut New Boxless Sawing In Half On Fashion Industry TV Drama". Genii magazine, August 2009, (Vol 72, No 8.).

- ^ Farmer, R., "David Copperfield Performs New Sawing In Half On Mischa Barton For TV Drama", Magic magazine, Vol.18 No.12 (August 2009).

- ^ Pete Hellard, "David Copperfield to bring magic act to Australia". Couriermail.com.au. March 15, 2009

- ^ "More Than Meets the Eye". The Sydney Morning Herald, August 7, 2009

- ^ Carol Cling (January 9, 2012). "Extras Wanted For 'Burt Wonderstone' Comedy". Las Vegas Review-Journal.

- ^ TODAY, Bryan Alexander, USA. "David Copperfield is the king of movie magic". USA TODAY. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "David Copperfield brings his magic to movies for 'Now You See Me 2'". Los Angeles Times. June 10, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "David Copperfield". Oprah's Next Chapter. July 15, 2012. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Graeber, Laurel (August 22, 2018). "Presto! A Museum Becomes a House of Illusion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Oldweiler, Cory (June 17, 2018). "New-York Historical Society's 'Summer of Magic' is rare chance to see Copperfield, Houdini artifacts | amNewYork". www.amny.com. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Burakoff, Maddie. "David Copperfield Welcomes New Citizens With a Magic Show and a History Lesson". Smithsonian. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Perks, Ashley (June 5, 2019). "David Copperfield says he'll restore 15th star on historic US flag". TheHill. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "Magic Television – Oprah: David Copperfield". Magic Television. February 19, 1996. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Singer, Mark (April 5, 1993). "Secrets of the Magus", The New Yorker, retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c Braxton, Greg (November 29, 2002). "Curator Copperfield". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ "International Museum and Library of the Conjuring Arts – MagicPedia". Genii. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ a b "Oprah's Next Chapter: Tour David Copperfield's Magic Museum" (Video). Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ Walker, Byron (February 2011). "Dr. Robert J. Albo". Linking Ring. 91 (2): 24–27.

- ^ Osterhout, Jacob E.; Bachner, Jeff (October 23, 2012). "New York gets first museum on famed magician Harry Houdini". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

Curator Roger Dreyer, head of Fantasma Toys Inc., spent two decades and millions of dollars amassing the second-largest Houdini collection in the world, behind only magician David Copperfield's. But Dreyer had nowhere to display his prized items.

- ^ "Houdini Museum of New York". NYC Arts. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "About Us". Houdini Museum of New York. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Tour David Copperfield's Magic Museum" (video). Oprah. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ a b —Jennifer Hall (March 1, 2009). "The Robb Reader: David Copperfield". Robb Report. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ "Magic Isles: David Copperfield's latest trick is a resort encompassing 11 Bahamian islands, The Robb Report, p. 72 (March 2009)

- ^ Dann, Caron (December 12, 2007). "Celebrity islands | Travel". News.com.au. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ Dubious Achievement Awards, 2006. Esquire February 20, 2007.

- ^ a b "Presto! A David Copperfield Magic Restaurant". The New York Times. July 13, 1997. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ "Unbuilt Disney-MGM Studios Concepts". waltdatedworld.com.

- ^ a b c Bagli, Charles V. (September 26, 1999). "Poof! $34 Million Vanishes on Broadway". The New York Times. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ Finnie, Shaun (2006). The Disneylands That Never Were. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-84728-543-0.[self-published source]

- ^ "Cost overruns stop Copperfield's construction". Nation's Restaurant News. September 21, 1998. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ "BW Online | October 19, 1998 | Talk Show". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

subcontractors slapped $15 million in liens on the project

- ^ Wagner, John (October 3, 2012). "It's no illusion: That's David Copperfield calling to promote gambling in Maryland". Washington Post. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- ^ Culver, Jordan. "Thousands of 'water bears' crash land on moon. They're practically indestructible". USA Today. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Chris (April 17, 2019). "There may be a copy of Wikipedia somewhere on the moon. Here's how to help find it". Mashable. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "David Copperfield's secret magic techniques crash-landed on the Moon". TechCrunch. April 15, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Magician has close call during underwater escape". The Pantagraph. Bloomington, Illinois. March 22, 1984. p. 18.

The diagnosis was basically abrasions and pulled tendons in arms and legs.

- ^ Wenzel, John (May 8, 2009). "Denver-bound Copperfield decries revealing of secrets". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ^ Lavine, Gail (2003). Rags To Riches: Motivating Stories Of How Ordinary People Achieved Extraordinary Wealth. iUniverse. p. 145. ISBN 0-595-30091-X.

- ^ "News - Exclusive: David Copperfield Assistant Rushed to Hospital During Las Vegas Show". Us Weekly. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ Andrews, Natalie (March 16, 2016). "David Copperfield Says Congress's Magical Move 'Means Everything'". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "David Copperfield Wants Congress To Believe In Magic". NPR.org. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "David Copperfield". MGM Grand Las Vegas. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "Hall of Fame: David Copperfield". Las Vegas Magazine. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "David Copperfield's Publishing Problem". Entertainment Weekly. August 5, 1994. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ^ "A judge says reporter Herbert Becker's "All the Secrets of Magic Revealed" can still go on sale in November". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. September 2, 1994. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2009 – via NewsBank.

- ^ "Magic book won't include Copperfield". Rome News-Tribune. 1994. Retrieved June 7, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "America's top two magicians locked in a legal battle". New Straits Times. 1997. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ "Fairytale romance that began with a cunning illusion – The Independent". www.independent.co.uk. London. July 11, 1997. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

The French magazine Paris Match claims that the meeting was a carefully calculated stunt, to boost Ms Schiffer's profile in the US and Copperfield's career in Europe. 'It was just a plot to dupe their loyal fans, and we've got the contracts to prove it,' said the magazine.

- ^ Luscombe, Belinda (August 4, 1997). "Copperfield V. Paris Match". Time. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

The suit states that Paris Match added that the supermodel now gets paid for pretending to be Copperfield's fiancée and doesn't even like him.

- ^ "Shedding Light: Copperfield talks candidly about his profession". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

Last year Copperfield slapped a $30 million lawsuit on Paris-Match magazine that alleged in a story that the Copperfield-Schiffer relationship was mere illusion; little more than a business deal to enhance both their careers.

- ^ Rush, George; Molloy, Joanna; Malkin, Marc S (August 29, 1999). "Copperfield's Claudia Clone". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Love, Honor and Portray". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 16, 1997. p. C5. ProQuest 391683984. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

Copperfield's publicist said he and Schiffer had contracts to do the 1993 show, but 'there is no contract that states Claudia is there as some sort of consort.'

- ^ "David Copperfield Sues Fireman's Fund". Insurance Journal, August 29, 2000

- ^ "Jury goes against magician". Las Vegas Review-Journal. March 12, 2003. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2009 – via www.accessmylibrary.com.

- ^ Philadelphia, Desa (January 24, 2000). "David Copperfield Has a New Assistant: the KGB". Time. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ a b "Property Owner Sued Copperfield Over Sale of Island Where Alleged Rape Occurred". FOX News. October 24, 2007. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ "Magic Star in $56.5 Mil Exuma Resort Row" Archived February 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Bahamas B2B.com, February 2, 2004

- ^ "Promoters Sue David Copperfield for $2.2 Million". Voice of America. 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ "David Copperfield rep says shows canceled over money". Daily News. New York. November 9, 2007. Archived from the original on January 12, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ "Indonesian promoter says he will hold Copperfield's stage props". Earth Times News. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ "Woman in David Copperfield's Rape Probe Arrested". ABC News. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ "Jury finds claims against David Copperfield unfounded in slip-and-fall case". May 30, 2018.

- ^ Carter, Mike (February 5, 2010). "Magician, pageant runner-up battle on in court". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ Barrett, Katherine (October 19, 2007). "Copperfield raid related to Bahamas incident". CNN.

- ^ "BBC News – David Copperfield 'rape' investigation closed". BBC. January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ Carter, Mike (January 26, 2010). "Woman who accused Copperfield of rape is now facing prostitution charge". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ Carter, Mike (March 23, 2010). "2011 trial date in lawsuit against magician Copperfield". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "Woman Drops Sexual Assault Suit Against David Copperfield - Trials & Lawsuits, David Copperfield". People. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ "Magician David Copperfield cleared of rape charges". News.com.au. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original on April 24, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ Fernandez, Alexia (January 24, 2018) "David Copperfield Accused of Sexually Assaulting Teen Model". People. Retrieved on 2018-02-02.

- ^ Saad, Nardine (January 25, 2018) "David Copperfield accused of drugging and assaulting model; 'don't rush to judgment,' illusionist says". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on February 2, 2018.

- ^ Bekiempis, Victoria (January 4, 2024) "Jeffrey Epstein: documents linking associates to sex offender unsealed". The Guardian. Retrieved on January 3, 2024

- ^ Style File: Claudia Schiffer (image #7). Archived June 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Vogue. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ Sophie Dahl and Jamie Cullum's secret wedding: 10. Claudia Schiffer and David Copperfield The Independent. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ David Copperfield Biography Archived February 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Ask Men. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ "Schiffer's big shift". Canoe.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

It was our work schedules that ended the relationship.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Magician David Copperfield robbed after show at Kravis Center". Palm Beach Post. April 25, 2006.

- ^ "David Copperfield tricks robbers". USA Today. April 26, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- ^ "TIL Illusionist David Copperfield was robbed at gunpoint and used sleight-of-hand to hide his wallet, passport, and cell phone". Reddit. February 3, 2015.

Yes... very stupid. It was a reflex that could have got me shot.

- ^ "David Copperfield Robbed At Gunpoint". The Smoking Gun. April 26, 2006.

- ^ "The Magicians' Podcast: Ep 100 - David Copperfield on Apple Podcasts". Apple Podcasts. September 26, 2023.

- ^ "Illusionist David Copperfield buys Las Vegas Summerlin home for $17.5M". July 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Celebrity 100". Forbes. June 20, 2002. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ "The World's Most Powerful Celebrities -". Forbes. June 3, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "#80 David Copperfield - The 2009 Celebrity 100". Forbes. June 3, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ "David Copperfield, Forbes Top Celebrities". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 19, 2005.

- ^ Basquille, Mark (May 2004). "David Copperfield to Captivate Seoul Audience". The Seoul Times.

- ^ a b "David Copperfield conjures therapeutic magic". USA Today. April 15, 2002. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ "Magician David Copperfield". Archived from the original on September 5, 2012.

Can performing magic tricks help disabled patients heal? Dr. Oz talks with illusionist David Copperfield about how magic has helped him and how, in turn, he is helping others through his organization Project Magic.

- ^ Sitting down with Cat Deeley On & Beyond, June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Celebs Give Back in 2019". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Las Vegas legend David Copperfield leading Bahama relief efforts". Las Vegas Review-Journal. September 11, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Day, Patrick Kevin (September 14, 2011). "David Copperfield Crowned First-Ever 'King of Magic'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Gaydos, Steven (September 25, 2013). "David Copperfield Has No Illusions About His New Film Prod'n Co. Red Safe". Variety. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Schawbel, Dan. "David Copperfield: How He Became The World's Most Successful Magician". Forbes. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Consider Nothing Impossible: David Copperfield's Illusions defy logic". archives.starbulletin.com. May 19, 1998. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Hall of Fame". The Academy of Magical Arts.

- ^ "David Copperfield Ride Of Fame Induction Ceremony". Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ "Jewish museum to honor magicians Houdini, David Copperfield". Associated Press. AP News. October 22, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Gershon, Livia. "How Harry Houdini and David Copperfield's Jewish Heritage Shaped Their Craft". Smithsonian. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Guinness World Records – Record Application Search". Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ The Morning Herald, 8 August 1986, page 35. Newspapers.com. Retrieved on February 2, 2018.

- ^ "The Magic of David Copperfield VIII, IX, X" (DVD Commentary), Standing Room Only Studios (2003)

- ^ "Copperfield will fight ice with fire". USA Today. April 3, 2001.

- ^ Bunnie Nichols Copperfield to change the world through magic. The Nation. March 12, 1997

- ^ David Copperfield coming to Barbara B. Mann - cape-coral-daily-breeze.com | News, sports, community info. Archived April 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Cape Coral Daily Breeze (January 17, 2009). Retrieved on February 15, 2012.

- ^ Oh My God (2009). IMDb.com

- ^ McNary, Dave (April 22, 2015). "Documentary 'Unity' Set for Aug. 12 Release with 100 Star Narrators". Variety. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

External links[edit]

- 1956 births

- American magicians

- American male film actors

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Fordham University alumni

- Las Vegas shows

- Living people

- Metuchen High School alumni

- New York University faculty

- People from Metuchen, New Jersey

- Philanthropists from New Jersey

- Academy of Magical Arts Magician of the Year winners