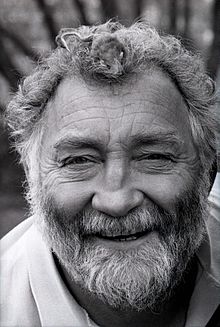

David Bellamy

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2019) |

David Bellamy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | David James Bellamy 18 January 1933 London, England |

| Died | 11 December 2019 (aged 86) Barnard Castle, England |

| Education | Sutton County Grammar School |

| Alma mater | Chelsea College of Science and Technology (BSc, 1957) Bedford College, London (PhD, 1960) |

| Occupation(s) | botanist, television presenter, author, environmental campaigner |

| Employer | Durham University |

| Spouse |

Rosemary Froy

(m. 1959; died 2018) |

| Children | 5 |

David James Bellamy OBE (18 January 1933 – 11 December 2019)[1] was an English botanist, television presenter, author and environmental campaigner.

Early and personal life[edit]

Bellamy was born at Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital in London to parents Winifred May (née Green) and Thomas Bellamy on 18 January 1933.[2][3] He was raised in a Baptist family and retained a strong Christian faith throughout his life.[4] As a child, he had hoped to be a ballet dancer, but he concluded that his rather large physique regrettably precluded him from pursuing the training.[3]

Bellamy went to school in south London, attending Chatsworth Road Primary School in Cheam, Cheam Road Junior School, and Sutton County Grammar School. He said that he "was never a model pupil".[2] He gained an honours degree in botany at Chelsea College of Science and Technology (now part of King's College London) in 1957 and a doctor of philosophy at Bedford College in 1960.[5]

Bellamy was influenced by Gene Stratton-Porter's 1909 novel A Girl of the Limberlost and Disney's 1940 film Fantasia.[3]

Bellamy married Rosemary Froy in 1959, and the couple remained together until her death in 2018.[2] They had five children: Henrietta (died 2017), Eoghain, Brighid, Rufus, and Hannah.[4] A resident of the Pennines in County Durham,[3][6] Bellamy died from vascular dementia at a care home in Barnard Castle on 11 December 2019, at the age of 86.[2]

Scientific career[edit]

Bellamy's first work in a scientific environment was as a laboratory assistant at Ewell Technical College[7] before he studied for a Bachelor of Science degree at Chelsea. In 1960 he became a lecturer in the botany department of Durham University.[8] The work that brought him to public prominence was his environmental consultancy on the Torrey Canyon oil spill in 1967, about which he wrote a paper in the leading scientific journal, Nature.[9]

[edit]

Bellamy published many scientific papers and books between 1966 and 1986 (see #Bibliography). Many books were associated with the TV series on which he worked. During the 1980s, he replaced Big Chief I-Spy as the figurehead of the I-Spy range of children's books, to whom completed books were sent to get a reward. In 1980, he released a single written by Mike Croft with musical arrangement by Dave Grosse to coincide with the release of the I-Spy title I Spy Dinosaurs (about dinosaur fossils) entitled "Brontosaurus Will You Wait For Me?" (backed with "Oh Stegosaurus"). He performed it on Blue Peter wearing an orange jump suit. It reached number 88 in the charts.[10]

Promotional and conservation work[edit]

In the early 1970s, Bellamy helped to establish Durham Wildlife Trust, and remained a key player in the conservation movement in the Durham area for a number of decades.[11]

The New Zealand Tourism Department, a government agency, became involved with the Coast to Coast adventure race in 1988 as they recognised the potential for event tourism. They organised and funded foreign journalists to come and cover the event. One of those was Bellamy, who did not just report from the event, but decided to compete. While in the country, Bellamy worked on a documentary series Moa's Ark that was released by Television New Zealand in 1990,[12][13] and he was awarded the New Zealand 1990 Commemoration Medal.[14]

Bellamy was the originator, along with David Shreeve and the Conservation Foundation (which he also founded), of the Ford European Conservation Awards.[15]

In 2002, he was a keynote speaker on conservation issues at the Asia Pacific Ecotourism Conference.[16]

In 2015, David Bellamy and his wife Rosemary visited Malaysia to explore its wildlife.[16]

In 2016, he opened the Hedleyhope Fell Boardwalk, which is the main feature of Durham Wildlife Trust's Hedleyhope Fell reserve in County Durham. The project includes a 60-metre path from Tow Law to the Hedleyhope Fell reserve, and 150 metres of boardwalk made from recycled plastic bottles.[17]

Broadcasting career[edit]

After Bellamy's TV appearances concerning the Torrey Canyon disaster, his exuberant and demonstrative presentation of science topics featured on programmes such as Don't Ask Me along with other scientific personalities such as Magnus Pyke, Miriam Stoppard, and Rob Buckman. He wrote, appeared in, or presented hundreds of television programmes on botany, ecology, environmentalism, and other issues. His television series included Bellamy on Botany, Bellamy's Britain, Bellamy's Europe and Bellamy's Backyard Safari.[18] He was regularly parodied by impersonators such as Lenny Henry on Tiswas with a "gwapple me gwapenuts" catchphrase. His distinctive voice was used in advertising.[19]

Activism[edit]

In 1983, Bellamy was imprisoned for blockading the Australian Franklin River in a protest against a proposed dam.[16] On 18 August 1984, he leapt from the pier at St Abbs Harbour into the North Sea; in the process, he officially opened Britain's first Voluntary Marine Reserve, the St. Abbs and Eyemouth Voluntary Marine Reserve.[20] In the late 1980s, he fronted a campaign in Jersey, Channel Islands, to save Queens Valley, the site of the lead character's cottage in Bergerac, from being turned into a reservoir because of the presence of a rare type of snail, but was unable to stop it.[21]

In 1997, he stood unsuccessfully at Huntingdon against the incumbent Prime Minister John Major for the Referendum Party. Bellamy credited this campaign with the decline in his career as a popular celebrity and television personality. In a 2002 interview, he said it was ill-advised.[22]

He was a prominent campaigner against the construction of wind farms in undeveloped areas, despite appearing very enthusiastic about wind power in the educational video Power from the Wind[23] produced by Britain's Central Electricity Generating Board.

David Bellamy was the president of the British Institute of Cleaning Science, and was a strong supporter of its plan to educate young people to care for and protect the environment. The David Bellamy Awards Programme is a competition designed to encourage schools to be aware of, and act positively towards, environmental cleanliness. Bellamy was also a patron of the British Homeopathic Association, and the UK plastic recycling charity Recoup from 1998.[2]

Views on global warming[edit]

In Bellamy's foreword to the 1989 book The Greenhouse Effect,[24] he wrote:

The profligate demands of humankind are causing far-reaching changes to the atmosphere of planet Earth, of this there is no doubt. Earth's temperature is showing an upward swing, the so-called greenhouse effect, now a subject of international concern. The greenhouse effect may melt the glaciers and ice caps of the world, causing the sea to rise and flood many of our great cities and much of our best farmland.

Bellamy's later statements on global warming indicate that he subsequently changed his views. A letter he published on 16 April 2005 in New Scientist asserted that a large proportion (555 of 625) of the glaciers being observed by the World Glacier Monitoring Service were advancing, not retreating.[25] George Monbiot of The Guardian tracked down Bellamy's original source for this information and found that it was from discredited data originally published by Fred Singer, who claimed to have obtained these figures from a 1989 article in the journal Science; however, Monbiot proved that this article had never existed.[26] Bellamy subsequently accepted that his figures on glaciers were wrong, and announced in a letter to The Sunday Times in 2005 that he had "decided to draw back from the debate on global warming",[27] although Bellamy jointly authored a paper with Jack Barrett in the refereed Civil Engineering journal of the Institution of Civil Engineers, entitled "Climate stability: an inconvenient proof" in May 2007.[28]

In 2008 Bellamy signed the Manhattan Declaration, calling for the immediate halt to any tax-funded attempts to counteract climate change.[29] He maintained a view that man-made climate change is "poppycock", insisting that climate change is part of a natural cycle.[30][31]

His opinions changed the way some organisations viewed Bellamy. The Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts stated in 2005, "We are not happy with his line on climate change",[32] and Bellamy, who had been president of the Wildlife Trusts since 1995,[11] was succeeded by Aubrey Manning in November 2005.[33] Bellamy asserted that his views on global warming resulted in the rejection of programme ideas by the BBC.[30][34]

Bibliography[edit]

Bellamy wrote or contributed to at least 45 books, including:

- Bellamy on Botany (1972) ISBN 0-563-10666-2

- Peatlands (1973)

- Bellamy's Britain (1974)

- Life Giving Sea (1975)

- Green Worlds (1975)

- The World of Plants (1975)

- It's Life (1976)

- Bellamy's Europe (1976)

- Natural History of Teesdale Chapter 7 Conservation & Upper Teesdale' (1976)

- Botanic Action (1978) ISBN 978-0091341411

- Botanic Man (1978) ISBN 978-0600314578

- Half of Paradise (1978) ISBN 978-0304297542

- Forces of Life: The Botanic Man (1979) ISBN 978-0517535295

- Bellamy's Backyard Safari (1981) ISBN 978-0563164685

- The Great Seasons (with Sheila Mackie, illustrator; Hodder & Stoughton, 1981) ISBN 978-0340257203

- Il Libro Verde (BOTANIC MAN). NATURAL AMBIENTE ECOLOGIA (SEI, 1981)

- Mouse Book: A Story of Apodemus, a Long-tailed Field Mouse (1983) ISBN 978-0853622000

- Bellamy's New world: A botanical history of America (1983) ISBN 978-0563165613

- The Queen's Hidden Garden (1984) ISBN 9780715385906

- David Bellamy's I-Spy Book of Nature 1985 (1985) ISBN 978-0850378252

- Bellamy's Bugle (1986)[citation needed]

- Bellamy's Ireland: The Wild Boglands (1986) ISBN 978-0747002161

- Turning The Tide. Exploring The Options For Life On Earth (1987) ISBN 978-0002193689

- The Roadside (Our Changing World) (1988) ISBN 978-0356135687

- England's Last Wilderness- A Journey Through the North Pennines (1989) ISBN 9780718131579

- Wetlands: An Exploration Of The Lost Wilderness Of East Anglia (1990) ISBN 978-0283999833

- Wilderness Britain? (1990, Oxford Illustrated Press, ISBN 1-85509-225-5)

- Moa's Ark (with Brian Springett and Peter Hayden, 1990) ISBN 9780670830985

- How Green Are You? (1991) ISBN 9780517584293

- Tomorrow's Earth: A Squeaky-green Guide (1991) ISBN 9780855339401

- World Medicine: Plants, Patients and People (1992) ISBN 9780631169338

- Blooming Bellamy: Guide to the Healing Herbs of Britain (1993) ISBN 978-0563367253

- Trees: A Celebration in Photographs (Introduction) (1994) ISBN 978-0517599631

- The Bellamy Herbal (2003) ISBN 978-0712683692

- Fabric Live: Bellamy Sessions (2004)[citation needed]

- Jolly Green Giant (autobiography, 2002, Century, ISBN 0-7126-8359-3)

- A Natural Life (autobiography, 2002, Arrow, ISBN 0-09-941496-1)

- Conflicts in the Countryside: The New Battle for Britain (2005), Shaw & Sons, ISBN 0-7219-1670-8

Discovering the Countryside with David Bellamy[edit]

Bellamy was "consultant editor and contributor" for this series, published by Hamlyn in conjunction with the Royal Society for Nature Conservation:

- Coastal Walks (1982; ISBN 0-600-35588-8)

- Woodland Walks (1982; ISBN 0-600-35658-2)

- Waterside Walks (1983; ISBN 0-600-35636-1)

- Grassland Walks (1983; ISBN 0-600-35637-X)

Forewords[edit]

Bellamy contributed forewords or introductions to:

- It's Funny About the Trees a collection of light verse by Paul Wigmore [Autolycus Press], ISBN 0 903413 96 5 (1998)

- Hidden Nature The Startling Insights of Viktor Schauberger by Alick Bartholomew, ISBN 978-0863154324 (2003)

- Chris Packham's Back Garden Nature Reserve New Holland Publishers, Chris Packham, (2001) ISBN 1-85974-520-2

- The Cosmic Fairy Arthur Atkinson [pseudonym for Arthur Moppett] [Colin Smythe Limited Publishers], 1996, ISBN 0-86140-403-3

- British Naturalists Association Guide to Woodlands J L Cloudsley-Thompson ISBN 978-0946284160 (1985)

- While the Earth Endures Creation, Cosmology and Climate Change Philip Foster [St Matthew Publishing Ltd]. ISBN 978-1901546316 (2008)

- Marine Fish and Invertebrates of Northern Europe Frank Emil Moen & Erling Svensen [KOM Publishing]. ISBN 0-9544060-2-8 (2004)

- The Lost Australia of François Péron Colin Wallace [Nottingham Court Press], ISBN 0-906691-96-6 (1984)

- Populate and Perish?, R. Birrell, D. Hill and J. Nevill, eds., Fontana/Australian Conservation Foundation (1984), ISBN 0 00 636728 3

Recognition[edit]

Bellamy also held these positions:

- Patron of Recoup (Recycling of Used Plastics), the national charity for plastics recycling

- Professor of Adult and Continuing Education, University of Durham

- Hon. Prof. Central Queensland University, Faculty of Engineering and Physical Systems

- Special Professor of Botany, (Geography), University of Nottingham

- Patron of the British Chelonia Group, For tortoise, terrapin and turtle care and conservation[35]

President of:

- The Wildlife Trusts partnership (1995-2005)[11]

- Wildlife Watch (1988-2005)[11]

- The Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country

- Durham Wildlife Trust[36]

- FOSUMS - Friends Of Sunderland Museums[37]

- The Conservation Foundation, UK

- Population Concern

- Plantlife

- WATCH

- Coral Cay Conservation[38]

- National Association for Environmental Education[39]

- British Naturalists' Association

- Galapagos Conservation Trust

- British Institute of Cleaning Science[40]

- Hampstead Heath Anglers Society[41]

- The Camping and Caravanning club[42]

- The Young People's Trust for the Environment.[43]

Vice president of:

- The Conservation Volunteers (TCV)[44]

- Fauna and Flora International

- Marine Conservation Society

- Australian Marine Conservation Society

- Nature in Art Trust[45]

Trustee, patron or honorary member of:

- Patron of National Gamekeepers' Organisation[46]

- Living Landscape Trust[47]

- World Land Trust (1992–2002)

- Patron of Southport Flower Show

- Patron, The Space Theatre, Dundee

- Hon Fellow Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management

- Chairman of the international committee for the Tourism for Tomorrow Awards.

- Patron of Butterfly World Project, St. Albans, UK[48]

- BSES Expeditions

- Patron, Project AWARE Foundation[49]

- Patron of Tree Appeal[50]

- Patron of RECOrd (Local Biological Records Centre for Cheshire)

- Patron of Ted Ellis Trust

Honours and awards[edit]

Bellamy was awarded an Honorary Dr. of Science, degree from Bournemouth University. He was the recipient of a number of other awards:

- The Dutch Order of the Golden Ark

- the U.N.E.P. Global 500 Award

- The Duke of Edinburgh's Prize (1969)[51]

- BAFTA, Richard Dimbleby Award

- BSAC Diver of The Year Award[citation needed]

- BSAC Colin McLeod Award, 2001[52]

In 2013, Professor Chris Baines gave the inaugural David Bellamy Lecture at Buckingham Palace to honour Bellamy's 80th birthday.[53] A second David Bellamy Lecture was given by Pete Wilkinson at the Royal Geographical Society in 2014.[54]

Chronology of TV appearances and radio broadcasts[edit]

|

|

See also[edit]

- Environmental movement

- Environmentalism

- Individual and political action on climate change

References[edit]

- ^ "TV naturalist David Bellamy dies aged 86". The Guardian. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Buczacki, Stefan (2023). "Bellamy, David James (1933–2019), botanist, broadcaster, and environmentalist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000380834. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d "My Secret Life: David Bellamy, broadcaster and botanist, 78". The Independent. 18 June 2011.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Pete (12 December 2019). "David Bellamy obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Professor David Bellamy OBE. "Professor David Bellamy OBE". www.royalholloway.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Elspeth (3 May 2006). "Counties of Britain: Durham by David Bellamy". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009.

- ^ Salter, Jessica (19 November 2009). "Eco hero: David Bellamy, botanist and campaigner". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Bellamy, David (2001). A Natural Life. Century.

- ^ Bellamy, D.J.; Clarke, P.H.; John, D.M.; Jones, D.; Whittick, A. (1 December 1967). "Effects of Pollution from the Torrey Canyon on Littoral and Sublittoral Ecosystems". Nature. 216 (5121): 1170–1173. Bibcode:1967Natur.216.1170B. doi:10.1038/2161170a0. S2CID 4201940.

- ^ "Official Charts Company". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 10 January 2018. [verification needed]

- ^ a b c d "David Bellamy - a tribute from The Wildlife Trusts". www.wildlifetrusts.org. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ McKerrow, Bob; Woods, John (1994). Coast to Coast: The Great New Zealand Race. Christchurch, New Zealand: Shoal Bay Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-908704-22-4.

- ^ "Moa's Ark". NZ on Screen. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Taylor, Alister; Coddington, Deborah (1994). Honoured by the Queen – New Zealand. Auckland: New Zealand Who's Who Aotearoa. p. 63. ISBN 0-908578-34-2.

- ^ "Awards – British Naturalists' Association". British Naturalists' Association. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Leadbeater, Chris (5 February 2016). "David Bellamy goes back to nature". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "David Bellamy on the boardwalk at Tow Law reserve". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Bellamy's Backyard Safari at Wild Film History. Retrieved 1 July 2014

- ^ Ribena UK Ltd. "Ribena". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ "St. Abbs & Eyemouth Voluntary Marine Reserve". www.marine-reserve.co.uk. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "BBC - Jersey - The Rock - Queen's Valley Reservoir". www.bbc.co.uk. 26 November 2004. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (30 September 2002), "The Green Man", The Guardian, London, retrieved 7 November 2008

- ^ Jenkins, N. (September 1990), "European Wind Energy", The Environmentalist, 10 (3): 230–231, doi:10.1007/BF02240360, S2CID 85265859.

- ^ Boyle, Stewart; Ardill, John (1989), The Greenhouse Effect, New English Library, ISBN 0-450-50638-X

- ^ "Glaciers are cool". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Monbiot, George (10 May 2005). "Junk Science". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ Bellamy, David (29 May 2005), In an Adverse Climate, London: Times Online, retrieved 7 November 2008

- ^ Bellamy, David; Barrett, David (1 May 2007), "Climate stability: an inconvenient proof", Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Civil Engineering, 160 (2), Thomas Telford Journals: 66–72, doi:10.1680/cien.2007.160.2.66, archived from the original on 15 September 2012

- ^ "Climate experts who signed the Manhattan Declaration". International Climate Science Coalition. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ a b Cahalan, Paul (14 January 2013). "David Bellamy: 'I was shunned. They didn't want to hear'". The Independent. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "David Bellamy tells of moment he was frozen out of the BBC". The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Leake, Jonathan (15 May 2005), Wildlife Groups Axe Bellamy as Global Warming 'Heretic', London: Times Online, retrieved 7 November 2008

- ^ "Wildlife Trusts roots out new city president". www.scotsman.com. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Bellamy, David. "The price of dissent on global warming". The Australian. (subscription required)

- ^ "British Chelonia Group - For tortoise, terrapin and turtle care and conservation". www.britishcheloniagroup.org.uk. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Trust statement following the death of David Bellamy. – Durham Wildlife Trust". Durham Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "All aboard for a heritage trip down memory lane". Sunderland Echo newspaper. 27 April 2005. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Science biography. "Science biography". www.coralcay.org. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Environmental Education. "Environmental Education" (PDF). naee.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Cleanzine. "David Bellamy OBE steps down as President of BICSc". www.bics.org.uk. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "東京脱毛サロン脱毛士の美肌促進ブログ". www.hhasoc.org. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Club History". www.campingandcaravanningclub.co.uk. 8 June 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Our Team - Presidents, Trustees and Staff - Young People's Trust For the Environment". Young People's Trust For the Environment. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Governance". The Conservation Volunteers. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Nature in Art – Trust". Nature in Art Trsut. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ^ "The National Gamekeepers Organisation Moorland Branch". Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ The Living Landscape Trust. "The Living Landscape Trust". opencharities.org. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Patrons". Butterfly World Project. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Project AWARE Homepage - Project AWARE". www.projectaware.org. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Trees and Us - Professor David Bellamy". www.treeappeal.co.uk. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Duke of Edinburgh's Prize - British Sub-Aqua Club". British Sub-Aqua Club. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Colin Mcleod Award". British Sub Aqua Club. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ "David Bellamy". www.bna-naturalists.org. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Veteran green says emissions aren't the only danger - Climate News Network". Climate News Network. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ IMDb. "David Bellamy". www.imdb.com. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ "Genome". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

External links[edit]

- Barrett Bellamy Climate climate science web site of Drs. David Bellamy and Jack Barrett

- David Bellamy Awards for Sustainability in Schools

- David Bellamy Conservation Awards

- Simon Hattenstone, The Guardian, 30 September 2002, "The green man" – Interview with David Bellamy

- New Scientist: 11 June 2005, British conservationist to lose posts after climate claims – Issue 2503, page 4

- Correspondence between David Bellamy and George Monbiot, 2004

- George Monbiot, The Guardian, 10 May 2005, "Junk science:David Bellamy's inaccurate and selective figures on glacier shrinkage are a boon to climate change deniers"

- Radio broadcast, Bellamy, David Suzuki, Janet Earle on marine conservation, RRR 102.7fm, Melbourne, 2002

- St. Abbs and Eyemouth Voluntary Marine Reserve Archived 3 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Britain's first Voluntary Marine Reserve opened by David Bellamy in August 1984.

- Today's forecast: yet another blast of hot air, The Times, 22 October 2007.

- Channel 4 Newsnight interview with David Bellamy and George Monbiot

- 1933 births

- 2019 deaths

- 20th-century Baptists

- 21st-century Baptists

- Academics of Durham University

- Alumni of Bedford College, London

- Alumni of King's College London

- Deaths from dementia in England

- Deaths from vascular dementia

- English Baptists

- English botanists

- English conservationists

- English environmentalists

- English expatriates in Australia

- English male non-fiction writers

- English non-fiction writers

- English television presenters

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People educated at Sutton Grammar School

- People from County Durham

- Referendum Party politicians

- Writers from London