China Airlines Flight 642

B-150, the aircraft involved in the accident in 1998, while still in service with Mandarin Airlines at Hong Kong International Airport | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 22 August 1999 |

| Summary | Crashed on landing due to pilot error |

| Site | Hong Kong International Airport 22°18′18″N 113°55′19″E / 22.305°N 113.922°E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas MD-11 |

| Operator | China Airlines |

| IATA flight No. | CI642 |

| ICAO flight No. | CAL642 |

| Call sign | DYNASTY 642 |

| Registration | B-150 |

| Flight origin | Don Mueang International Airport |

| Stopover | Hong Kong International Airport |

| Destination | Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport |

| Occupants | 315 |

| Passengers | 300 |

| Crew | 15 |

| Fatalities | 3 |

| Injuries | 208 (44 serious, 164 minor) |

| Survivors | 312 |

China Airlines Flight 642 was a flight that crashed at Hong Kong (Chep Lap Kok) International Airport on 22 August 1999. It was operating from Bangkok (Bangkok International Airport, now renamed as Don Mueang International Airport) to Taipei with a stopover in Hong Kong.[1]

The plane, a McDonnell Douglas MD-11 (registration B-150), was still carrying Mandarin Airlines' livery from its time of service with the carrier. While landing during a typhoon, it touched down hard, flipped over and caught fire. Of the 315 people on board, 312 survived and three were killed.[2] It was the first fatal accident to occur at the new Hong Kong International airport since it opened in July 1998.[3]

Flight 642 was one of only two hull losses of MD-11s with passenger configuration, the other being Swissair Flight 111, which crashed in 1998 with 229 fatalities. All other hull losses of MD-11s have been when the aircraft has been serving as a cargo aircraft.[4]

Aircraft and crew[edit]

The aircraft was a McDonnell Douglas MD-11 registered as B-150, which had been delivered to China Airlines in October 1992. The aircraft was powered by three Pratt & Whitney PW4460 turbofan engines.[5]: 13–19 [6][7] B-150 had been involved in an earlier unrelated incident as CAL012 on 7 December 1992 when moderate turbulence led to the aircraft departing normal flight, leading to it sustaining damage to its outboard elevator skin assemblies, some of which broke off from the aircraft.[8][9] B-150 was then delivered to China Airlines's subsidiary Mandarin Airlines in July 1993. It was then returned to China Airlines in March 1999.[6]

The captain was 57-year-old Gerardo Lettich, an Italian national who had joined China Airlines in 1997, and had previously flown for a major European airline. He had 17,900 flight hours, including 3,260 hours on the MD-11. The first officer was 36-year-old Liu Cheng-hsi, a Taiwanese national who had been with the Airline since 1989 and had logged 4,630 flight hours, with 2,780 of them on the MD-11.[5]: 9–13 [10]

Summary[edit]

At about 6:43 P.M. local time (10:43 UTC) on 22 August 1999, the MD-11 was making its final approach to runway 25L when Tropical Storm Sam was 50 kilometres (31 mi; 27 nmi) NE of the airport. At an altitude of 700 feet (210 m) prior to touchdown a further wind check was reported to the crew: 320 deg/28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) gusting to 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph). This resulted in a crosswind vector of 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) gusting to 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph), while the tested limit for the aircraft was 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph).

During the final flare to land, the plane rolled to the right, landed hard on its right main gear and the No. 3 engine touched the runway. The right wing separated from the fuselage. The aircraft continued to roll over and skidded off the runway in flames. When it stopped, it was on its back and the rear of the plane was on fire, coming to rest on a grass area next to the runway, 3500 ft from the runway threshold. The right wing was found on a taxiway 280 feet (85 m) from the nose of the plane.[11] As shown in photos of the aircraft at rest, the fire caused significant damage to the rear section of the aircraft but was quickly extinguished due to the heavy rain and quick response from rescue teams in the airport.

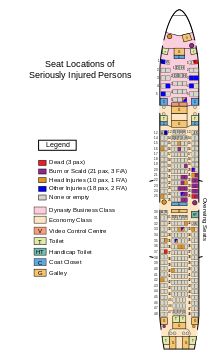

Rescue vehicles quickly arrived on the scene and suppressed the fire on and in the vicinity of the aeroplane, allowing rescue of the passengers and crew to progress in very difficult conditions. Two passengers rescued from the wreckage were certified dead on arrival at hospital and one passenger died five days later in hospital.[12] A total of 219 persons, including crewmembers, were admitted to hospital, of whom 50 were seriously injured and 153 sustained minor injuries. All 15 crew members survived.[5]: 7

Investigation[edit]

The final report of the accident blamed it mainly on pilot error, specifically the inability to arrest the high rate of descent existing at 50 feet (15 m) altitude on the radar altimeter. The descent rate at touch down was 18–20 feet per second (5.5–6.1 m/s).

The flight data stored in the volatile memory of the aircraft's Quick Access Recorder (QAR) during the last 500 feet (150 m) of the approach could not be recovered due to the interruption of the power supply at impact. Probable wind variations and the loss of headwind component, together with the early retardation of thrust levers, led to a 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) loss in indicated airspeed just prior to touchdown.[5]

Due to the severe weather conditions forecast for Hong Kong, the flight crew had prepared to divert the flight to Taipei if the situation at Hong Kong was deemed unsuitable for landing. Extra fuel was carried for this possibility, resulting in a landing weight of 429,557 lb (194,844 kg), 99.897% of its maximum landing weight of 430,000 lb (200,000 kg). Based on the initial weather and wind check which was passed along to the crew from Hong Kong during the flight, they believed they could land there and decided against a diversion to Taipei. However, four earlier flights had carried out missed approaches at Hong Kong and five had diverted.

During the final approach, the plane descended along the Instrument Landing System (ILS) glideslope until at about 700 feet (210 m), the crew visually acquired the runway. They disengaged the autopilot but left the autothrottle on. During the flare, the rate of descent was not arrested, the plane landed with the right wing slightly lower. The right landing gear touched down first, the right engine impacted the runway and the right wing was detached from the fuselage. Since the left wing was still attached, the lift from that wing rolled the fuselage onto its right side, and the plane came to rest inverted in the grass strip next to the runway. The spilled fuel caught fire.[5]

Several suggestions were given to China Airlines concerning its training.[5] However, China Airlines disputed the report's findings on the flight crews' actions, citing the weather conditions at the time of the accident and claimed that the aircraft flew into a microburst just before landing, causing it to crash.[13]

Aftermath[edit]

As of 2016[update] the route continues to operate with the flight no longer originating in Bangkok and is strictly a Hong Kong-Taipei route. Bangkok-Hong Kong service ended on 31 October 2010. Both non-stop routes are now flown by the Airbus A330-300.[14]

Media[edit]

The landing and crash of Flight 642 was recorded by nearby occupants in a car. The video, which also captured reactions from the witnesses, has been uploaded to websites such as YouTube and Airdisaster.com.[15]

A photo showing a Mandarin Airlines MD-11 taxiing past the remains of Flight 642 was circulated.[16]

The crash was mentioned in Episode 7 of the first Season Extreme Engineering, despite many details being incorrect in the episode.

This disaster was also aired on RTHK's Elite Brigade II Episode 2 in 2012.

See also[edit]

- Martinair Flight 495 – a DC-10 that broke up after a hard landing under similar weather conditions in 1992

- Lufthansa Cargo Flight 8460 – an MD-11 that bounced and broke up on landing in 2010

- FedEx Express Flight 80 – an MD-11 that bounced and flipped on landing in 2009

- FedEx Express Flight 14 – an MD-11 that bounced and flipped on landing in 1997

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

References[edit]

- ^ Murphy, Colum (5 February 2005). "Pilot error blamed for typhoon crash". The Standard. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas MD-11 B-150 Hong Kong-Chek Lap Kok International Airport (HKG)". aviation-safety.net. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Sunday's Hong Kong crash fourth accident in past decade". CNN. Reuters. 22 August 1999. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "MD-11 hull losses". aviation-safety.net. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Report on the accident to Boeing MD11 B-150 at Hong Kong International Airport on 22 August 1999" (PDF). www.cad.gov.hk. Hong Kong: Civil Aviation Department. December 2004. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ a b "B-150 China Airlines McDonnell Douglas MD-11". www.planespotters.net. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "China Airlines B-150 (McDonnell Douglas MD-11 - MSN 48468)". www.airfleets.net. Airfleets aviation. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas MD-11 B-150 Kushimoto". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "In-flight turbulence encounter and loss of portions of the elevators, China Airlines Flight CI-012, McDonnell Douglas MD-11-P, Taiwan registration B-150, About 20 miles east of Japan, December 7, 1992" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 15 February 1994. NTSB/AAR-94/02. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ Lee, Ella; Lee, Stella (22 September 1999). "Pilots urged to attend meeting with Taiwan aviation heads". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Accident Bulletin on China Airlines". www.info.gov.hk. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "2 die, more than 200 hurt in Hong Kong jet crash". CNN. 22 August 1999. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "China Airlines Disputes Official Finding of Pilot Error". www.defensedaily.com. Defense Daily. 14 February 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "China Airlines (CI) #642". FlightAware. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "Airdisaster.com video of China Airlines Flight 642". Airdisaster.com. Archived from the original on 9 December 2003. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "A Difficult Cabin Announcement". Snopes.com. 11 January 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

External links[edit]

| External image | |

|---|---|

- Civil Aviation Department

- (in English) Video of the incident on YouTube

- (in Spanish) Video of the incident on YouTube

- Li, Alex Fu-hing. "Air crash rescuers praised for courage and gallantry". Civil Service Bureau. Archived from the original on 4 December 2000.

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 1999

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by weather

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error

- Aviation accidents and incidents in Hong Kong

- Accidents and incidents involving the McDonnell Douglas MD-11

- China Airlines accidents and incidents

- Hong Kong International Airport

- 1999 in Hong Kong

- 1999 meteorology

- August 1999 events in Asia