Charles Tennant

Charles Tennant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 3 May 1768 |

| Died | 1 October 1838 (aged 70) |

| Occupation(s) | Businessperson, chemist, industrialist |

| Parent(s) | John Tennant Margaret McClure |

| Family | Tennant |

Charles Tennant (3 May 1768 – 1 October 1838) was a Scottish chemist and industrialist. He discovered bleaching powder and founded an industrial dynasty.

Biography[edit]

Charles Tennant was born at Laigh Corton, Alloway, Ayrshire, the sixth of thirteen surviving children of farmer John "Auld Glen" Tennant (1725–1810), later of Glenconner, Ochiltree, Ayrshire, and his second wife, Margaret McClure (1738–1784). He was educated at home and at the Ochiltree parish school, then was apprenticed by his father to a master handloom weaver at Kilbarchan in Renfrewshire. The Tennant family were friends with the poet Robert Burns (1759–1796); in his epistle to "James Tennant of Glenconner" Tennant is mentioned as "wabster (Scots language: weaver) Charlie", in reference to the occupation Tennant had undertaken.[1][2][3]

Impetus[edit]

Tennant was quick to learn his trade, but also to see that the growth of the weaving industry was restricted by the primitive methods used to bleach the cloth. At that time this involved treatment with stale urine and leaving the cloth exposed to sunlight for many months in so called bleachfield. Huge quantities of unbleached cotton piled up in the warehouses. Tennant left his well paid weaving position to try to develop improved bleaching methods.

He acquired bleaching fields in 1788, at Darnley, near Barrhead, Renfrewshire, and turned his mind and energy to developing ways to shorten the time required in bleaching. Others had already managed to reduce bleaching time from eighteen months to four by replacing sour milk with sulfuric acid.[citation needed] Further, in the last half of the eighteenth century, bleachers started to use lime in the bleaching process, but only in secret due to possible injurious effects. Tennant had the original idea that a combination of chlorine and lime would produce the best bleaching results. He worked on this idea for several years and was finally successful. His method proved to be effective, inexpensive and harmless. He was granted patent #2209 on 23 January 1798. He continued his research and developed a bleaching powder for which he was granted patent #2312 on 30 April 1799.[4]

St Rollox Chemical Works[edit]

While still working in the bleachfields around the year 1794, Tennant formed a partnership with four friends. The first of these, Dr. William Couper, was the legal advisor to the partnership. The second partner was Alexander Dunlop (His brother married Charles' eldest daughter), who served as accountant to the group. The third partner, James Knox, managed the sales department. Charles Macintosh, an excellent chemist, was the fourth partner. He is known for his technique of macintosh waterproofing[citation needed] and he also assisted in the invention of bleaching powder.

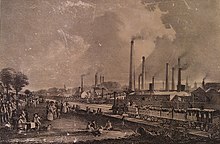

Immediately after granting of the patent on bleaching, Charles and his partners purchased land on the Monkland Canal, just north of Glasgow, to build a factory for the production of bleaching liquor and powder. The area was known as St. Rollox, after a French holy man. It was close to a good supply of lime, and since the area was rural, the land was cheap. Additionally, the nearby canal provided excellent transportation. Production was swiftly moved from the earlier bleachfields in Darnley, to the new plant in St. Rollox. It quickly became successful. Production increased from fifty-two tons the first year, 1799, to over 9200 tons the fifth year. Later a second plant was built at Hebburn, raising production of bleaching powder alone to 20 000 tons by 1865.

In 1798 James Knox and Robert Tennant (Charles younger brother), went to Ireland where they struck a deal with the Irish bleachers, for the use of the process. Although the Irish bleachers admitted a saving of over £160,000 in 1799 alone, by using the Tennant process, they never paid for its use as agreed. As a result, the partnership lost a great deal in time and money. Further losses came from challenges to the patents in England and Ireland and the outright infringement of the process. In spite of these worrisome problems the partnership was a great success. It continued for fourteen years when the rights under the patents expired.

Charles continued to expand his horizons during this time. When the partnership ended he purchased the company. As a forward thinking business man, he was in a class by himself. His company, during the 1830s and 1840s was the largest chemical plant in the world.[citation needed]

Reformer[edit]

As a dedicated reformer Charles played his full part in the movements of the day. A great deal of unrest followed the Napoleonic wars, which had the effect of increased wealth for the manufacturing classes but poverty for the working classes. Charles and his son John were active in a time liberal views could be construed as treason. He worked for many years in the reform movement, but it was not until he reached the age of sixty-four that his effort bore fruit with the passage of the Reform Bill of 1832. Following on from the success of the reform Bill of 1832 Charles appears to have been a leading light in the movement to honour Scotland's Political Martyr Thomas Muir of Huntershill, A public dinner was organised to take place on 17 January 1838, Charles was to chair the event at Mosesfield house, the home of James Duncan Esq. Unfortunately Charles was indisposed and unable to attend. His ideas and active support helped create one of the most productive periods of social progress and reform, in almost every area, in Scotland's history.

Charles Tennant, in spite of the many demands on his time from outside sources, never lost sight of the main business in his life, the St. Rollox chemical works. By the year 1832, St. Rollox was consuming thirty thousand tons of coal a year. The system had not been designed to handle this volume. It just could not do so efficiently. He plunged into a study of possible solutions to the problem. His imagination and interest were fired by a new way of transporting people and freight. This involved using wagons, pulled by a steam engine, on iron rails laid on a level roadbed. He had heard of this from his good friend George Stephenson, the great railway engineer. He quickly realised this was the answer to his problem at St. Rollox. From 1825 until his death he was one of the prime movers in railway expansion. He was mainly responsible for getting a railway into Glasgow, over the fierce opposition of the canal proprietors.

Never one to overlook a sideline, Charles decided he must not forget the waterways. In 1830 he started his younger sister Sarah's son, William Sloan, with some small schooners. He saw this as a way to control the transportation of chemical products to nearby markets. At the time of Sloan's death in 1848 they had the largest fleet in Glasgow, and were running nineteen vessels.

Charles lived to see his empire grow to be the largest and most important in the world. He was, beyond question, an entrepreneur of amazing ability. His dedication to his work, his family and his sense of what was right and fair lasted until the day he died. He was quick to champion those less fortunate, and the reforms he initiated and supported made the lives of his countrymen better. On his death on 1 October 1838, his eldest son John Tennant became managing director of Charles Tennant & Co for the next 40 years. Amongst other diverse business interests, he also became a partner in the Bonnington Chemical Works.[5]

Discovery[edit]

With the chemist Charles Macintosh (1766–1843) he helped establish Scotland's first alum works at Hurlet, Renfrewshire. In 1798 he took out a patent for a bleach liquor formed by passing chlorine into a mixture of lime and water. This product had the advantage of being cheaper than the one generally used at the time because it substituted lime for potash. Unfortunately when Tennant attempted to protect his rights against infringement, his patent was held invalid on the double ground that the specification was incomplete and that the invention had been anticipated at a bleach works near Nottingham. Tennant's great discovery was bleaching powder (chloride of lime) for which he took a patent in 1799. The process involved reacting chlorine and dry slaked lime to form bleaching powder, a mixture of calcium hypochlorite and other derivatives. It seems Macintosh also played a significant role in this discovery and remained one of Tennant's associates for many years.

Fortune[edit]

In 1800 Tennant founded a chemical works at St. Rollox, Glasgow.[6] The principal product being bleaching powder (calcium hypochlorite), which was sold worldwide. By 1815 the business was known as Charles Tennant & Co. and had expanded into other chemicals, metallurgy and explosives. The early rail network in Scotland and important mines in Spain were also areas of interest.

The St. Rollox plant grew to be the largest chemical works in the world during the 1830s and 1840s. It covers over 100 acres (0.4 km2) and had 250,000 square feet (23,000 m2) of floor space. It had a payroll of over one thousand persons and dominated the local economy. The huge chimney known as the St. Rollox Stalk aka Tennant's Stalk towered over everything. It was a well-known landmark around Glasgow. Built in 1842, it rose a majestic 435.5 feet (132.7 m) in the air.[7] It was 40 feet (12.2 m) in diameter at ground level.[8] At the time of construction it was the tallest such structure in the world (losing the accolade 17 years later to the Townsend Chimney, located less than a mile away at Port Dundas).[9] In 1922 it was struck by lightning and had to be dynamited down – four workmen died when part of the structure collapsed during the process[10] – but until that time it was in daily use.

Legacy[edit]

Tennant died at his home at Abercromby Place[11] in Glasgow on 1 October 1838. He is buried in Glasgow Necropolis where his monument stands on the upper plateau. The unusual statue thereon is in the form of a very casually (arguably slumped) seated figure. The sculpture is by Patrick Park (1811–1855) and appears to be based on Francis Chantrey's statue of James Watt in the nearby Hunterian Museum.

The mighty business empire Tennant founded and the immense wealth generated soon expanded even further with major initiatives in explosives with Alfred Nobel, copper, sulphur, gold mines and banking [12] His grandson Charles Clow Tennant (1823–1906) became the 1st baronet of Glenconner. The chemical business founded by Tennant became known as the United Alkali Company Ltd. and eventually merged with others in 1926 to form the chemical giant Imperial Chemical Industries. The chemical works at Springburn closed in 1964. Outwith ICI and its successors the privately owned group, now Tennants Consolidated Ltd., continues with headquarters in London and chemicals, colours and distribution trade with every continent.

Notable descendants and relatives[edit]

- Alexander Tennant (1772–1814) brother

- Charles Clow Tennant (1823–1906) grandson

- Edward Tennant, 1st Baron Glenconner (1859–1920) great grandson

- Margot Asquith (1864–1946) great granddaughter

- Harold Tennant (1865–1935) great grandson

- Edward Tennant (1897–1916) 2nd great grandson

- Elizabeth Bibesco (1897–1945) 2nd great granddaughter

- Anthony Asquith (1902–1968) 2nd great grandson

- Stephen Tennant (1906–1987) 2nd great grandson

- Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat (1911–1995) 3rd great grandson

- Hugh Fraser (British politician) (1918–1984) 3rd great grandson

- Harold Tennyson, 4th Baron Tennyson (1919–1991) 3rd great grandson

- Charles Manners, 10th Duke of Rutland (1919–1999) 3rd great grandson

- Iain Tennant (1919–2006) 3rd great grandson

- David Fane, 15th Earl of Westmorland (1924–1993) 3rd great grandson

- Emma Tennant (b. 1937) 3rd great granddaughter

- Arthur Gore, 9th Earl of Arran (b. 1938) 4th great grandson

- Torquhil Campbell, 13th Duke of Argyll (b. 1968) 5th great grandson

- Stella Tennant (1970-2020) 4th great granddaughter

- Honor Fraser (b. 1974) 5th great granddaughter

Notes[edit]

- ^ "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27131. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Charles Tennant - National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk.

- ^ "Society of Chemical Industry - Charles Tennant".

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2019). "Bonnington Chemical Works (1822-1878): Pioneer Coal Tar Company". International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology. 89 (1–2): 73–91. doi:10.1080/17581206.2020.1787807. S2CID 221115202.

- ^ "Ordnance Survey 25 inch 1892-1914". Explore georeferenced maps. National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Jenkins, Moses (2021). Scotland's Tall Chimneys. Pugmill Press. p. 30. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Bancroft, Robert; Bancroft, Francis (1885). Tall Chimney Construction (PDF). Lewes: Farncombe and Co. p. 37. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ When Glasgow had the Tallest Chimney(s) in the World, A Hauf Stop, 20 July 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2022

- ^ Tennants Chimney Collapse and Demolition 1922, A Hauf Stop, July 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2022

- ^ Glasgow Post Office Directory 1838

- ^ "Charles Tennant and Co - Graces Guide".

References[edit]

- Crathorne, Nancy (1973). Tennants Stalk The story of the Tennants of the Glen. London: MacMillan, The Nancy Crathorne Memorial Trust.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Harden, Arthur (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 56. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Lindsey, Christopher F. "Tennant, Charles (1768–1838)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27131. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Sources[edit]

- Poems and Songs of Robert Burns publisher: London, Collins, 1955 ISBN 1-4264-0558-8 OCLC 53420849.

- Blow, Simon (1987), Broken Blood – The Rise and Fall of the Tennant family. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-13374-6 OCLC 16470862.

- Dugdale, Nancy (1973). Tennant's Stalk: the story of the Tennants of the Glen. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-13820-1. OCLC 2736092.

- The will of Charles Tennant (1768–1838) 1840 Glasgow Sheriff Court Wills ref: SC36/51/16.

- The will of Margaret Wilson (1766–1843) 1845 Glasgow Sheriff Court Wills ref: SC36/51/21.

- Ordnance Survey map of Ayrshire 1860.

- Ordnance Survey map of Renfrewshire 1863.

- An Avant-Garde Family: A History of the Tennants.

- 1768 births

- 1838 deaths

- People from South Ayrshire

- People associated with Glasgow

- People of the Industrial Revolution

- Scottish industrialists

- Scottish chemists

- Scottish inventors

- Scottish company founders

- Tennant family

- Burials at the Glasgow Necropolis

- Springburn

- People from Ochiltree

- 18th-century Scottish businesspeople

- 19th-century Scottish businesspeople