Adam Duncan, 1st Viscount Duncan

The Viscount Duncan | |

|---|---|

Portrait by John Hoppner, c.1798 | |

| Born | 1 July 1731 Dundee, Angus, Scotland |

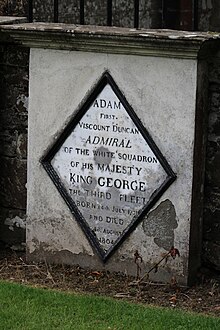

| Died | 4 August 1804 (aged 73) Cornhill-on-Tweed, Northumberland, United Kingdom |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1746–1804 |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Naval Gold Medal |

Admiral Adam Duncan, 1st Viscount Duncan, KB (1 July 1731 – 4 August 1804) was a British admiral who defeated the Dutch fleet off Camperdown on 11 October 1797. This victory is considered one of the most significant actions in naval history.[1]

Life[edit]

Adam was the second son of Alexander Duncan, Baron of Lundie, Angus, (d. May 1777) Provost of Dundee, and his wife (and first cousin once removed) Helen, daughter of John Haldane of Gleneagles. He was born at Dundee. In 1746, after receiving his education in Dundee, he entered the Royal Navy on board the sloop Trial, under Captain Robert Haldane, with whom, in HMS Trial and afterwards in HMS Shoreham, he continued until the peace in 1748. In 1749, he was appointed to HMS Centurion, then commissioned for service in the Mediterranean, by the Hon. Augustus Keppel (afterwards Viscount Keppel), with whom he was afterwards in HMS Norwich on the coast of North America, and was confirmed in the rank of lieutenant on 10 January 1755.[1]

Seven Years War[edit]

In August 1755, he followed Keppel to Swiftsure, and in January 1756 to Torbay, in which he continued until his promotion to commander's rank on 21 September 1759, and during this time was present in the expedition to Basque Roads in 1757, at the reduction of Gorée in 1758, and in the blockade of Brest in 1759, up to within two months of the Battle of Quiberon Bay, from which his promotion just excluded him.[1]

From October 1759 to April 1760, he had command of Royal Exchange, a hired vessel employed in petty convoy service with a miscellaneous ship's company, consisting to a large extent of boys and foreigners, many of whom (he reported) could not speak English, and all impressed with the idea that as they had been engaged by the merchants from whom the ship was hired they were not subject to naval discipline. It would seem that a misunderstanding with the merchants on this point was the cause of the ship's being put out of commission after a few months.[1]

As a commander, Duncan had no further service, but on 25 February 1761, he was posted and appointed to HMS Valiant, fitting for Keppel's broad pennant. In her he had an important share in the reduction of Belle Île in June 1761, and of Havana in August 1762. He returned to Britain in 1763, and, notwithstanding his repeated request, had no further employment for many years.[1]

Peacetime[edit]

During this time, he lived principally at Dundee, and married Henrietta, daughter of Robert Dundas of Arniston, Lord President of the Court of Session on 6 June 1777. It would seem that his alliance with this influential family obtained him the employment which he had been vainly seeking during fifteen years. Towards the end of 1778, he was appointed to HMS Suffolk, from which he was almost immediately moved into HMS Monarch.[1]

In January 1779, he sat as a member of the court-martial of Admiral Keppel for the poor performance of the Channel Fleet during the First Battle of Ushant. During the course of the trial Duncan objected several times to stop the prosecutor in irrelevant and in leading questions, or in perversions of answers. The Admiralty was therefore desirous that he should not sit on the court-martial of Sir Hugh Palliser for failure to obey orders during the same battle. The court-martial was set for April. The day before the assembling of the court the admiralty sent down orders for Monarch to go to St. Helens. Her crew, however, refused to weigh the anchor until they were paid their advance; and as this could not be done in time, Monarch was still in Portsmouth harbour when the signal for the court-martial was made;[2] so that, sorely against the wishes of the admiralty, Duncan sat on this court-martial also.[1]

During the summer of 1779, Monarch was attached to the Channel fleet under Sir Charles Hardy; in December was one of the squadrons with which Rodney sailed for the relief of Gibraltar, and had a prominent share in the action off St. Vincent on 16 January 1780. On returning to Britain, Duncan quit Monarch, and had no further command until after the change of Ministry in March 1782, when Keppel became first lord of the admiralty. He was then appointed to HMS Blenheim of 90 guns, and commanded her during the year in the Grand Fleet under Howe, at the relief of Gibraltar in October, and the encounter with the allied fleet off Cape Spartel. He afterwards succeeded Sir John Jervis in command of Foudroyant, and after the peace commanded HMS Edgar as guardship at Portsmouth for three years. He attained flag rank on 24 September 1787, became vice admiral 1 February 1793, and was promoted to admiral 1 June 1795. In February 1795, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief, North Sea, and hoisted his flag on board HMS Venerable.[3]

In action with the Dutch[edit]

During the first two years of Duncan's command, the work was limited to enforcing a rigid blockade of the enemy's coast, but in the spring of 1797, it became more important from the knowledge that the Dutch fleet in the Texel was getting ready for sea.[4]

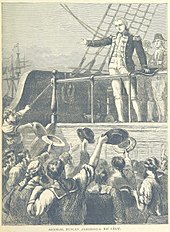

The situation was one of extreme difficulty, for the mutiny which had paralysed the fleet at the Nore broke out also amongst the crews under Duncan, and kept him for some weeks in enforced inactivity. Duncan's personal influence and some happy displays of his vast personal strength held the crew of Venerable to their duty; but with one other exception, that of Adamant, the ships refused to quit their anchorage at Yarmouth, leaving Venerable and Adamant alone to keep up the pretence of the blockade.[4]

Fortunately, the Dutch were not at the time ready for sea; and when they were ready and anxious to sail, with thirty thousand troops, for the invasion of Ireland, a persistent westerly wind detained them in harbour until they judged that the season was too far advanced.[5] For political purposes, however, the French Revolutionaries who controlled the government in Holland (despite the contrary opinion of their admiral, De Winter), ordered him to put to sea in the early days of October.[4]

Duncan, with the main body of the fleet, was at the time lying at Great Yarmouth revictualling, the Texel being watched by a small squadron under Captain Henry Trollope in HMS Russell, from whom he received early information of the Dutch being at sea. He at once weighed anchor, and with a fair wind approached the Dutch coast, saw that the fleet was not returned to the Texel, and steering towards the south sighted it on the morning of 11 October about seven miles from the shore and nearly halfway between the villages of Egmont and Camperdown. The wind was blowing straight on shore, and though the Dutch forming their line to the north preserved a bold front, it was clear that if the attack was not made promptly they would speedily get into shoal water, where no attack would be possible. Duncan at once realised the necessity of cutting off their retreat by getting between them and the land. At first, he was anxious to bring up his fleet in a compact body, for his numbers were at best equal to those of the Dutch; but seeing the absolute necessity of immediate action, without waiting for the ships astern to come up, without waiting to form line of battle, and with the fleet in very irregular order of sailing, in two groups, led respectively by himself in Venerable and Vice-admiral Richard Onslow in Monarch, he made the signal to pass through the enemy's line and engage to leeward.[4]

It was a bold departure from the absolute rule laid down in the Fighting Instructions, still new, though warranted by the more formal example of Howe on 1 June 1794; and on this occasion, as on the former, was crowned with complete success. The engagement was long and bloody; for though Duncan, by passing through the enemy's line, had prevented their untimely retreat, he had not advanced further in tactical science, and the battle was fought out on the primitive principles of ship against ship, the advantage remaining with those who were the better trained to the great gun exercise,[6] though the Dutch inflicted great loss on the Royal navy.[4]

It had been proposed to De Winter to make up for the want of skill by firing shell from the lower deck guns, and some experiments had been made during the summer which showed that the idea was feasible.[7] However, want of familiarity with an arm so new and so dangerous presumably prevented its being acted on in the battle.[4]

Rewards[edit]

The news of the victory was received in Britain with the warmest enthusiasm. It was the first certain sign that the mutinies of the summer had not destroyed the power and the prestige of the Royal Navy. Duncan was at once (21 October) raised to the peerage as Viscount Duncan, of Camperdown, and Baron Duncan, of Lundie in the Shire of Perth (with which came the lands now known as Camperdown Park in Dundee), and there was a strong feeling that the reward was inadequate. Even as early as 18 October his aunt, Lady Mary Duncan, wrote to Henry Dundas, at that time secretary of state for war: Report says my nephew is only made a Viscount. Myself it is nothing, but the whole nation thinks the least you can do is to give him an English earldom. … Am sure were this properly represented to our good king, who esteems a brave, religious man like himself, would be of my opinion. ….[8] It was not, however, until 1831, many years after Duncan's death, that his son, then bearing his title, was raised to the dignity of an earl, and his other children to the rank and precedence of the children of an earl.[9]

Duncan was awarded the Large Naval Gold Medal and an annual pension of £3,000, to himself and the next two heirs to his title – this was the biggest pension ever awarded by the British government. Additionally, he was given the freedom of several cities, including Dundee and London.[10]

Death[edit]

Duncan continued in command of the North Sea fleet until 1801, but without any further opportunity of distinction. Three years later, 4 August 1804, he died quite suddenly, aged seventy-three, at the inn at Cornhill, a village on the border, where he had stopped for the night on his journey to Edinburgh (ib. 252) and was buried in Lundie west of Dundee.[10]

Memorial[edit]

There is a memorial to him within St Paul's Cathedral.[11]

Character[edit]

Duncan was of size and strength almost gigantic. He is described as 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) in height, and of corresponding breadth. When a young lieutenant walking through the streets of Chatham, his grand figure and handsome face attracted crowds of admirers, and to the last he is spoken of as singularly handsome.[12]

Nelson wrote to Duncan's son, Henry, a fellow Royal Navy officer, on 4 October 1804, including a newspaper with the account of Duncan's death, "There is no man who more sincerely laments the heavy loss you have sustained than myself; but the name of Duncan will never be forgot by Britain, and in particular by its navy, in which service the remembrance of your worthy father will, I am sure, grow up in you. I am sorry not to have a good sloop to give you, but still an opening offers which I think will insure your confirmation as a commander".[13]

Family[edit]

Duncan's uncle was Sir William Duncan, physician-extraordinary to King George III and first of the Duncan baronets.[14] On 6 June 1777 Duncan married Henrietta (1749–1832), daughter of Robert Dundas of Arniston, Lord President of the Court of Session. On his death Duncan left a family of four daughters and two sons. His eldest son succeeded to the peerage and later became Earl of Camperdown; the second son, Henry, died a captain in the navy and K.C.H. in 1835.[10]

His sister Margaret was mother to James Haldane Tait who served under him several times and rose to the rank of Rear Admiral.[15]

Henrietta and her children are buried in Canongate Kirkyard in Edinburgh east of the church.

Heraldry[edit]

The paternal arms of the 1st Viscount were: Gules, two cinquefoils in chief and a bugle horn in base argent stringed azure (Clan Duncan).[16] In the centre of his paternal coat the 1st Viscount was granted an augmentation of honour: Pendant by a ribbon argent and azure from a naval crown or a gold medal thereon two figures the emblems of Victory and Britannia; Victory alighting on the prow of an antique vessel, crowning Britannia with a wreath of laurel; and below the word "Camperdown"

Crest: A first rate ship of war, with masts broken, rigging torn and in disorder, floating on the sea, all proper and over, the motto "Disce Pati" ("learn to suffer").

Supporters: On the dexter side an Angel, mantle purpure; on the head a celestial crown; the right hand supporting an anchor proper; in the left a palm branch Or. On the sinister a sailor, habited and armed proper; his left hand supporting a staff, thereon hoisted a flag azure; the Dutch colours, wreathed about the middle of the staff. Motto: "Secundis Dubiisque Rectus"[17][18]

Recognition[edit]

- Several ships have been named HMS Duncan, or Admiral Duncan (ship), or Lord Duncan (ship) after him.

- The Dundee Unit of the Sea Cadets is named TS Duncan after him.

- A statue by Westmacott, erected at the public expense, is in St. Paul's.[10]

- Duncan Terrace in Islington, London N1 was named after him.[19]

- Duncan Street in Leeds town centre is named after him. The pub on this street honours him with its name and many pictures and paintings.

- The Galapagos island, now known as Pinzón Island, was named Duncan Island.

- A statue of Duncan was erected in 1997 in his birthplace, Dundee, on the corner of High Street and Commercial Street.

- Several public houses are named after him, including the Admiral Duncan pub in Soho, London,[20] a gay pub that was the scene of a terrorist bombing in 1999.

- namesake of Duncan's Cove, Nova Scotia

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Laughton 1888, p. 159.

- ^ Laughton 1888, p. 159 cites Considerations on the Principles of Naval Discipline, 8vo, 1781, p. 106n.

- ^ Laughton 1888, pp. 159–160.

- ^ a b c d e f Laughton 1888, p. 160.

- ^ Laughton 1888, p. 160 cites Life of Wolfe Tone, ii. 425–435.

- ^ Laughton 1888, p. 160 cites Chevalier, Histoire de la Marine Française sous la première République, 329

- ^ Laughton 1888, p. 160 cites Life of Wolfe Tone, ii. 427

- ^ Laughton 1888, pp. 160–161 cites Arniston Memoirs, 251.

- ^ Laughton 1888, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b c d Laughton 1888, p. 161.

- ^ "Memorials of St Paul's Cathedral" Sinclair, W. p. 453: London; Chapman & Hall, Ltd; 1909.

- ^ Laughton 1888, p. 161 cites Colburn's New Monthly Magazine, 1836, xlvii. 466.

- ^ Laughton 1888, p. 161 cites Nelson Despatches vi. 216.

- ^ Burke, John; Burke, Sir Bernard (1841). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Extinct and Dormant Baronetcies of England, Ireland and Scotland (2nd ed.). Scott, Webster, and Geary. p. 176.

- ^ Marshall, John (1827). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 162–165.

- ^ Naval Chronicle, Volume 4, London, 1801, edited by James Stanier Clarke, John Jones, Stephen Jones, Heraldic Particulars relative to Lord Viscount Duncan, p.113 [1]

- ^ Naval Chronicle, Volume 4, London, 1801

- ^ For image of heraldic achievement see

- ^ Early London County Courts : a brief account of their history and buildings. [Place of publication not identified]: Anthony Bradbury. 2010. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-9566442-0-6. OCLC 1285558728.

- ^ Rothwell, David (2006). The dictionary of pub names. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. p. 11. ISBN 1-84022-266-2. OCLC 352936023.

References[edit]

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Laughton, John Knox (1888). "Duncan, Adam". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 159–161. Endnotes:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Laughton, John Knox (1888). "Duncan, Adam". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 159–161. Endnotes:

- Ralfe's Naval Biography, i. 319;

- Naval Chronicle, iv. 81;

- Charnock's Biographia Navalis, vi. 422;

- James's Naval History of Great Britain (edit. 1860), ii. 74;

- Keppel's Life of Viscount Keppel.

Further reading[edit]

- Crimmin, P. K. (January 2008) [2004]. "Duncan, Adam, Viscount Duncan (1731–1804)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8211. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Rampant Scotland - Famous Scots - Adam Duncan, 1st Viscount Camperdown (1731–1804)

- Taynet - Admiral Lord Duncan, Hero of Camperdown

- Gazetteer for Scotland - Admiral Adam Duncan

- The Naval Chronicle, Volume 4 1800, J. Gold, London. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01843-2)

- 1731 births

- 1804 deaths

- People educated at the High School of Dundee

- Military personnel from Dundee

- Nobility from Dundee

- Royal Navy admirals

- Royal Navy personnel of the American Revolutionary War

- Royal Navy personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars

- Royal Navy personnel of the Seven Years' War

- Viscounts in the Peerage of Great Britain

- Peers of Great Britain created by George III