A Bucket of Blood

| A Bucket of Blood | |

|---|---|

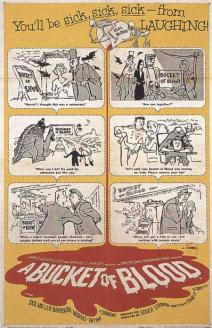

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roger Corman |

| Screenplay by | Charles B. Griffith |

| Produced by | Roger Corman |

| Starring | Dick Miller Barboura Morris Antony Carbone |

| Cinematography | Jacques R. Marquette |

| Edited by | Anthony Carras |

| Music by | Fred Katz |

Production company | Alta Vista Productions[1] |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 65 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50,000[2][3] |

| Box office | $180,000[3] |

A Bucket of Blood is a 1959 American comedy horror film directed by Roger Corman. It starred Dick Miller and was set in the West Coast beatnik culture of the late 1950s. The film, produced on a $50,000 budget, was shot in five days[2] and shares many of the low-budget filmmaking aesthetics commonly associated with Corman's work.[4] Written by Charles B. Griffith, the film is a dark comic satire[2][5] about a dimwitted, impressionable young busboy at a Bohemian café who is acclaimed as a brilliant sculptor when he accidentally kills his landlady's cat and covers its body in clay to hide the evidence. When he is pressured to create similar work, he becomes a serial murderer.[6]

A Bucket of Blood was the first of a trio of collaborations between Corman and Griffith in the comedy genre, which include The Little Shop of Horrors (which was shot on the same sets as A Bucket of Blood)[7] and Creature from the Haunted Sea. Corman had made no previous attempt at the genre, although past and future Corman productions in other genres incorporated comedic elements.[2] The film is a satire not only of Corman's own films but also of the world of abstract art as well as low-budgeted teen films of the 1950s. The film has also been praised in many circles as an honest, undiscriminating portrayal of the many facets of beatnik culture, including poetry, dance, and a minimalist style of life.[citation needed] The plot has similarities to Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). However, by setting the story in the Beat milieu of 1950s Southern California, Corman creates an entirely different mood from the earlier film.[8]

Plot[edit]

One night after hearing the words of Maxwell H. Brock, a poet who performs at The Yellow Door cafe, the dimwitted, impressionable, busboy Walter Paisley returns home to attempt to create a sculpture of the face of the hostess Carla. He stops when he hears the meowing of Frankie, the cat owned by his inquisitive landlady, Mrs. Surchart, who has somehow gotten himself stuck in Walter's wall. Walter attempts to get Frankie out using a knife, but accidentally kills the cat when he sticks the knife into his wall. Instead of giving Frankie a proper burial, Walter covers the cat in clay, leaving the knife stuck in it.

The next morning, Walter shows the cat to Carla and his boss Leonard. Leonard dismisses the oddly morbid piece, but Carla is enthusiastic about the work and convinces Leonard to display it in the café. Walter receives praise from Will and the other beatniks in the café. An adoring fan, Naolia, gives him a vial of heroin to remember her by. Naively ignorant of its function, he takes it home and is followed by Lou Raby, an undercover cop, who attempts to take him into custody for narcotics possession. In a blind panic, thinking Lou is about to shoot him, Walter hits him with the frying pan he is holding, killing Lou instantly.

Meanwhile, Walter's boss discovers the secret behind Walter's Dead Cat piece when he sees fur sticking out of it. The next morning, Walter tells the café-goers that he has a new piece, which he calls Murdered Man. Both Leonard and Carla come with Walter as he unveils his latest work and are simultaneously amazed and appalled. Carla critiques it as "hideous and eloquent" and deserving of a public exhibition. Leonard is aghast at the idea, but realizes the potential for wealth if he plays his cards right.

The next night, Walter is treated like a king by almost everyone, except for a blonde model named Alice, who is widely disliked by her peers. Walter later follows her home and confronts her, explaining that he wants to pay her to model. At Walter's apartment, Alice strips nude and poses in a chair, where Walter proceeds to strangle her with her scarf. Walter creates a statue of Alice which, once unveiled, so impresses Brock that he throws a party at the Yellow Door in Walter's honor. Costumed as a carnival fool, Walter is wined and dined to excess.

After the party, Walter later stumbles towards his apartment. Still drunk, he beheads a factory worker with his own buzzsaw to create a bust. When he shows the head to Leonard, the boss realizes that he must stop Walter's murderous rampage and promises Walter a show to offload his latest "sculptures". At the exhibit, Walter proposes to Carla, but she rejects him. Walter is distraught and now offers to sculpt her, and she happily agrees to after the reception. Back at the exhibit, however, she finds part of the clay on one figure has worn away, revealing Alice's finger. When she tells Walter that there is a body in one of the sculptures, he tells her that he "made them immortal", and that he can make her immortal, too. She flees, he chases, and the others at the exhibit learn Walter's secret and join the chase. Walter and Carla wind up at a lumber yard where Walter, haunted by the voices of Lou and Alice, stops chasing Carla, and runs home. With discovery and retribution closing in on him, Walter vows to "hide where they'll never find me". The police, Carla, Leonard, Maxwell, and the others break down Walter's apartment door only to find that Walter has hanged himself. Looking askance at the hanging, clay-daubed corpse, Maxwell proclaims, "I suppose he would have called it Hanging Man ... his greatest work."

Cast[edit]

- Dick Miller as Walter Paisley

- Barboura Morris as Carla

- Antony Carbone as Leonard de Santis

- Julian Burton as Maxwell H. Brock

- Ed Nelson as Art Lacroix

- John Brinkley as Will

- John Herman Shaner as Oscar

- Judy Bamber as Alice

- Myrtle Vail as Mrs. Swickert

- Bert Convy as Detective Lou Raby

- Jhean Burton as Naolia

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

I, being a young director and knowing a lot of young directors and writers, hung out with a group that could be considered vaguely beatnik. I was not a beatnik, however. When we made A Bucket of Blood, the beat scene was more or less at its peak... A Bucket of Blood was ultimately an affectionate satire on a movement that was soon to be replaced by the hippie generation. [9]

– Roger Corman, 2016

In the middle of 1959, American International Pictures approached Roger Corman to direct a horror film—but only gave Corman a $50,000 budget and a five-day shooting schedule—plus leftover sets from Diary of a High School Bride (1959).[10]

Corman accepted the challenge but later said he was uninterested in producing a straightforward horror film. He claims he and screenwriter Charles B. Griffith developed the idea for producing a satirical black comedy horror film about the beatnik culture.[11]

Charles Griffith later claimed Corman was very uneasy at the idea of making a comedy "because you have to be good. We don't have the time or money to be good, so we stick to action."[12] Griffith says he talked Corman around by pointing out that since the film was made for such a little amount of money over such a short schedule, he could not fail to make money.[12]

Corman says that the genesis of the film was an evening he and Griffith "spent drifting around the beatnik coffeehouses, observing the scene and tossing ideas and reactions back and forth until we had the basic story."[13] The director says by the end of the evening they developed the film's plot structure,[2] partially basing the story upon Mystery of the Wax Museum.[11]

Griffith says Corman was uneasy about how to direct comedy, and Griffith, whose parents were in vaudeville, advised him that the key was to ensure the actors played everything straight.[12]

Shooting[edit]

The film was shot under the title The Living Dead,[14] and filming started 11 May 1959.[15][16]

According to actor Antony Carbone, "[The production] had a kind of spirit of 'having fun,' and I think [Corman] realized that while making the film. And I feel it helped him in other films he made, like The Little Shop of Horrors−he carried that Bucket of Blood 'idea' into that next film."[14]

Actor Dick Miller was unhappy with the film's low production values. Miller is quoted by Beverly Gray as stating that,

If they'd had more money to put into the production so we didn't have to use mannequins for the statues; if we didn't have to shoot the last scene with me hanging with just some gray make-up on because they didn't have time to put the plaster on me, this could have been a very classic little film. The story was good; the acting was good; the humor in it was good; the timing was right; everything about it was right. But they didn't have any money for production values ... and it suffered.[4]

Release[edit]

American International Pictures' theatrical marketing campaign emphasized the comedic aspects of the film's plot, proclaiming that the audience would be "sick, sick, sick—from laughing!",[17] a reference to cartoonist Jules Feiffer's popular Village Voice comic strip and his 1958 book with the same title. The film's poster consists of a series of comic strip panels humorously hinting at the film's horror content.[citation needed]

According to Tim Dirks, the film was one of a wave of "cheap teen movies" released for the drive-in market. They consisted of "exploitative, cheap fare created especially for them [teens] in a newly established teen/drive-in genre."[18]

When Corman found that the film "worked well", he continued to direct two more comedic films scripted by Griffith:[2] The Little Shop of Horrors, a farce with a similar plot to Bucket of Blood and using the same sets;[5][7] and Creature from the Haunted Sea, a parody of the monster movie genre.

The film was acquired by MGM Home Entertainment upon the company's purchase of Orion Pictures, which had owned the AIP catalog. MGM released A Bucket of Blood on VHS and DVD in 2000.[19][20] MGM re-released the film as part of a box set with seven other Corman productions in 2007. However, the box set featured the same menus and transfer as MGM's previous edition of the film.[21]

Reception[edit]

From a contemporary review, the Monthly Film Bulletin stated that although "the horror ultimately becomes rather too explicit, this macabre satire on beatniks and teenage horror films has some particularly adroit dialogue and tragi-comic situations."[22] The review praised Dick Miller, who "gives a performance of sustained poignancy as the half-wit hero."[22]

In a retrospective review, Sight & Sound referred to the film as "Corman's best work" with "hilarious dialogue and a finale reminiscent of Fritz Lang's M" and that his "low-budget comedy horror pic works both as satire at the expense of the Beat generation and as a trenchant little allegory about the New York art world in general."[23]

Corman later said the film "wasn't a huge success, but I think we were ahead of our time because The Raven, which is a triumph, is far less funny. Maybe the film was too modest, filmed in five days on sets that came from a film about youth. The distributors didn't know what to make of a movie that didn't belong to any particular genre. They were always scared of comedy."[24]

Adaptations[edit]

The film was remade for television in 1995 under the same name, although the remake was also distributed under the title The Death Artist. The remake was directed by comedian Michael McDonald and starred Anthony Michael Hall and Justine Bateman. The cast also included cameos by David Cross, Paul Bartel, Mink Stole, Jennifer Coolidge and Will Ferrell.

A musical production of A Bucket of Blood was produced by Chicago's Annoyance Theatre in 2009.[25] It opened September 26, and closed October 31, 2009, garnering exceptional reviews,[26] including a recommendation from the Chicago Reader.[27] The musical was directed by Ray Mees, with music by Chuck Malone. The cast included James Stanton as Walter Paisley, Sam Locke as Leonard, Peter Robards as Maxwell, Jen Spyra as Carla, Colleen Breen as Naolia, Maari Suorsa as Alice, Tyler Patocka as William and Peter Kremidas as Lee.[25] Another musical adaptation is currently[when?] in development, retitled Beatsville. It features a book by Glenn Slater and music and lyrics by Wendy Wilf.[28]

In March 2023, the La Mirada Theatre premiered a musical adaption of A Bucket of Blood entitled Did You See What Walter Paisley Did Today?[29]Although no promotional material ever directly stated that Walter Paisley was an adaptation of Bucket of Blood, the plot and characters of the musical are identical to those of the film, including exact character names. The only major difference is the ending, in which Walter falls into a concrete mixer rather than hanging himself. The show featured a libretto by Randy Rogel and choreography by Connor Gallagher, as well as direction by BT McNicholl, and ran from March 16, 2023 to April 2, 2023.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "A Bucket of Blood". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Corman, Roger; Jerome, Jim (August 22, 1998). How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime. Da Capo Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 0-306-80874-9.

- ^ a b Isenberg, Barbara (May 5, 1970). "Formula flicks". The Wall Street Journal. ProQuest 133440245.

- ^ a b Gray, Beverly (2004). Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-555-2.

- ^ a b Graham, Aaron W. "Little Shop of Genres: An interview with Charles B. Griffith". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on January 25, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ Gary A. Smith, The American International Pictures Video Guide, McFarland 2009 p 35

- ^ a b "Fun Facts". A Bucket of Blood (Media notes). MGM Home Entertainment. 2000. ISBN 079284680X.

- ^ Wright, Gene (1986). Horrorshow. New York: Facts on File Publications. ISBN 0-8160-1014-5. p. 4.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (2016). "Interview: Roger Corman Remembers 1959's A BUCKET OF BLOOD". p. ComingSoon.net.

- ^ Mark McGee, Faster and Furiouser: The Revised and Fattened Fable of American International Pictures, McFarland, 1996 p145

- ^ a b Clarens, Carlos (1997). An Illustrated History of Horror and Science-Fiction Films. Da Capo Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-306-80800-5.

- ^ a b c Beverly Gray, Roger Corman: Blood Sucking Vampires, Flesh Eating Cockroaches and Driller Killers AZ Ferris Publications 2014 p 48

- ^ Roger Corman, "Wild Imagination: Charles B. Griffith 1930–2007", LA Weekly 17 October 2007 Archived April 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine accessed 20 April 2014

- ^ a b Weaver, Tom (2004). Science Fiction and Fantasy Film Flashbacks: Conversations with 24 Actors, Writers, Producers and Directors from the Golden Age. McFarland & Company. pp. 64–67. ISBN 0-7864-2070-7.

- ^ "FILMLAND EVENTS: Ilona Massey Signed for Airplane Drama". Los Angeles Times. May 5, 1959. p. A13.

- ^ "Briefs from the Lots". Variety. May 6, 1959. p. 15.

- ^ "Taglines for A Bucket of Blood (1959)". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on June 22, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "The History of Film – The 1950s: The Cold War and Post-Classical Era, The Era of Epic Films, and the Threat of Television, Part 1". Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ^ A Bucket of Blood. ISBN 0792845544.

- ^ A Bucket of Blood. ISBN 079284680X.

- ^ "Roger Corman Collection". ASIN B000SK5ZFC. Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ a b "Bucket of Blood, A, U.S.A., 1959". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 27, no. 312. British Film Institute. 1960. p. 6.

- ^ Tunney, Tom; Macnab, Geoffrey (January 1997). "A Bucket of Blood". Sight & Sound. Vol. 7, no. 1. British Film Institute. p. 59.

- ^ Nasr, Constantine (2011). Roger Corman: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers. University Press of Mississippi. p. 10.

- ^ a b "The Annoyance Theatre and Bar". Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ [1] [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Chicago Reader". June 9, 2011. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "New Music: NAMT Announces Selections for 2008 Festival of New Musicals - Playbill.com". February 6, 2016. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Gans, Andrew. "La Mirada World Premiere of New Musical "Did You See What Walter Paisley Did Today?" Begins March 16th". Playbill.com. Playbill.

External links[edit]

- A Bucket of Blood at IMDb

- A Bucket of Blood at AllMovie

- A Bucket of Blood at the American Film Institute Catalog

- A Bucket of Blood at the TCM Movie Database

- A Bucket of Blood at Rotten Tomatoes

- A Bucket of Blood is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- A Bucket of Blood on YouTube

- A Bucket of Blood on Livestream

- 1959 films

- 1959 black comedy films

- 1959 comedy horror films

- 1950s satirical films

- 1950s teen films

- American black-and-white films

- American black comedy films

- American comedy horror films

- American International Pictures films

- American satirical films

- 1950s English-language films

- Films about the Beat Generation

- Films about sculptors

- Films directed by Roger Corman

- Films produced by Roger Corman

- Films set in apartment buildings

- American serial killer films

- American exploitation films

- 1950s American films

- Films about landlords