Zoran Milanović

Zoran Milanović | |

|---|---|

Milanović in 2021 | |

| President of Croatia | |

| Assumed office 19 February 2020 | |

| Prime Minister | Andrej Plenković |

| Preceded by | Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović |

| Prime Minister of Croatia | |

| In office 23 December 2011 – 22 January 2016 | |

| President | Ivo Josipović Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović |

| Deputy | Radimir Čačić Branko Grčić Milanka Opačić Vesna Pusić |

| Preceded by | Jadranka Kosor |

| Succeeded by | Tihomir Orešković |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 22 January 2016 – 26 November 2016 | |

| Prime Minister | Tihomir Orešković Andrej Plenković |

| Preceded by | Tomislav Karamarko |

| Succeeded by | Davor Bernardić |

| In office 2 June 2007 – 23 December 2011 | |

| Prime Minister | Ivo Sanader Jadranka Kosor |

| Preceded by | Ivica Račan Željka Antunović (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Jadranka Kosor |

| President of the Social Democratic Party | |

| In office 2 June 2007 – 26 November 2016 | |

| Deputy | Zlatko Komadina Gordan Maras Milanka Opačić Rajko Ostojić |

| Preceded by | Ivica Račan Željka Antunović (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Davor Bernardić |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 October 1966 Zagreb, SR Croatia, Yugoslavia |

| Political party | Independent (2020–present)[a] |

| Other political affiliations | Social Democratic Party (1999–2020) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Official website |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Premiership

Elections President of Croatia

Elections  |

||

Zoran Milanović (pronounced [zǒran milǎːnoʋitɕ] ⓘ;[2] born 30 October 1966) is a Croatian politician serving as the president of Croatia since 2020. Prior to assuming the presidency, he was prime minister from 2011 to 2016, as well as president of the Social Democratic Party from 2007 to 2016.

After graduating from the Zagreb Faculty of Law, Milanović started working in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He served as Advisor at the Croatian mission to the European Union and NATO in Brussels from 1996 to 1999. During the same year he joined the Social Democratic Party. In 1998 he earned his master's degree in European Union law at the Free University Brussels and was an assistant to the Croatian foreign minister for political multilateral affairs in 2003. In June 2007 he was elected president of the SDP, following the death of the long-time party leader and former prime minister Ivica Račan. Under Milanović's leadership the party finished in second place in the 2007 parliamentary election and was unable to form a governing majority. Despite losing the election, he was reelected party leader in 2008. In 2011 Milanović initiated the formation of the Kukuriku Coalition, uniting four centre to centre-left political parties. The coalition won an absolute majority in the 2011 parliamentary election, with the SDP itself becoming the largest party in Parliament. Milanović thus became Prime Minister on 23 December 2011, after the Parliament approved his cabinet.

The beginning of his prime ministership was marked by efforts to finalise the ratification process of Croatia's entry into the European Union and by the holding of a membership referendum. His cabinet introduced changes to the tax code, passed a fiscalisation law and started several large infrastructure projects. After the increase in the value of the Swiss franc, the government announced that all Swiss franc loans would be converted into euros. Milanović supported the expansion of same-sex couples' rights and introduced the Life Partnership Act. After the inconclusive 2015 election and more than two months of negotiations on forming a government, he was ultimately succeeded as prime minister by the nonpartisan technocrat Tihomir Orešković in January 2016. After Orešković's government fell, Milanović led the four-party People's Coalition in the subsequent snap parliamentary election in September 2016. In the election, his coalition suffered a surprise defeat to the centre-right Croatian Democratic Union and Milanović announced his withdrawal from politics. He then entered the consulting business and worked as an advisor to Albanian prime minister Edi Rama.

On 17 June 2019, Milanović announced that he would be running for the office of president in the 2019–20 election as the candidate of the Social Democratic Party; he was officially nominated on 6 July. He received the most votes (29.55%) in the first round of the election on 22 December 2019, ahead of incumbent president Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović (26.65%) and was elected as the fifth president of Croatia in the runoff on 5 January 2020, with 52.66% of the vote. He became the first presidential candidate in Croatian history to receive more votes than an incumbent officeholder in the first round of an election, the second person in Croatia to defeat an incumbent running for reelection and the first (post-independence) prime minister of Croatia to be elected head of state.

Background[edit]

His father, Stipe Milanović (1937–2019), was an economist, and his mother, Đurđica "Gina" (née Matasić), is a former teacher of English and German.[3]

His paternal family hails from the Sinj environs.[4] He stated that his father's family roots going back a century or two are from Livno, Bosnia and Herzegovina.[5] His paternal grandfather and paternal great-uncle, Ante and Ivan Milanović, respectively, from Glavice, joined the Yugoslav Partisans in 1942, taking part later in the liberation of Trieste. His maternal family Matasić is an old Senj bourgeois family, with some distant roots in Lika, Gacka valley. His maternal grandmother and grandfather were Marija (née Glavaš) and Stjepan Matasić, respectively. Their daughter Đurđica, Milanović's mother, was born and raised in Senj with three other siblings. Stjepan Matasić was killed in 1943 when the Allies bombed German-occupied Senj. Marija then moved with her children to Sušak, where she met Petar Plišić, a blacksmith from Ličko Lešće, whom she married and moved together with him to Zagreb, where they raised Đurđica and the rest of her siblings. Plišić, was—as Milanović revealed in 2016—an Ustasha, a member of the paramilitary corps established by the Nazi-collaborationist government of the Independent State of Croatia. After World War II, he served two years in Stara Gradiška prison before being released.[4][6][7]

Zoran's father was a member of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ).[4] Milanović was baptized secretly by his maternal grandmother Marija at the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Zagreb, and given the baptismal name Marijan.[3] He was brought up in the neighbourhoods of Knežija, and after 1970 in Trnje, a communist quarter.[3] He had a brother, Krešimir, who died in 2019.[8] Milanović attended the Center for Management and Judiciary from 1981.[3][9]

Milanović partook in sports, including football, basketball and boxing. He declared himself as a leftist.[3] In 1985, he entered the University of Zagreb to study law, then finished his military service, and returned to study in 1986.[3] After college, Milanović became an intern at the Zagreb Commercial Court, and in 1993 for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, working under future political rival Ivo Sanader. A year later, he joined an OSCE peacekeeping mission in the Nagorno-Karabakh region, disputed between Armenian natives and Azerbaijan.[10]

In 1994, he married his wife Sanja Musić, with whom he has two sons: Ante Jakov, and Marko.[11][12] Apart from Croatian, he speaks English, French, and Russian.[citation needed]

Party president[edit]

In 1999, he joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP) as he had not yet been an official member. Following SDP's win in the 2000 elections, he was given responsibility for liaison with NATO; three years later he became assistant to Foreign Minister Tonino Picula. He left his post after the 2003 elections when the conservative Croatian Democratic Union came to power.

As an SDP member, in 2004 he renounced his position as an assistant minister of foreign affairs and became a member of the newly founded SDP's executive committee as well as the International Secretary in charge of contacts with other political parties. Two years later, he briefly became party spokesman, standing in for absent Gordana Grbić. In early September 2006 he became SDP's coordinator for the 4th constituency in the 2007 elections.

An extraordinary party convention was held in Zagreb on 2 June 2007, due to 11 April resignation of the first party president and Croatia's former prime minister Ivica Račan. Milanović entered the contest, despite being considered an "outsider", because of his shorter term in the party, running against Željka Antunović (acting party president since Račan's resignation), Milan Bandić and Tonino Picula. On 29 September 2007, during the campaign for party president, he publicly promised to resign and never to seek presidency of the party again, if party did not win more seats than HDZ in next elections.[13]

In the first round he led with 592, well ahead of his nearest rival, Željka Antunović.[14] He won the second round, thereby becoming president of the party.[15]

2007 parliamentary election[edit]

The 2007 parliamentary election turned out to be the closest election since independence with SDP winning 56 seats, only 10 mandates short of HDZ's 66. 5 seats that HDZ had won were from the eleventh district reserved for citizens living abroad, which was one of the main campaign issues of SDP which sought to decrease electoral significance of the so-called diaspora voters. The resulting close race left both sides in a position to form a government, provided they gather 77 of the 153 representatives. After the election, Sanader seemed to be in a better position to form a cabinet which caused Milanović to make himself the candidate for prime minister over the less popular Ljubo Jurčić, without first consulting the party's Main Committee. However, the Social Democrats remained in the Opposition, since Ivo Sanader managed to form a majority coalition.[citation needed]

After losing the hotly contested general elections, Milanović did not resign as party president, despite promising before the election that he would, should the party lose.[13] In the 2007 election, despite the loss, SDP emerged with the largest parliamentary caucus in their history and achieved their best result yet. Milanović seemed to be in a good position to remain party president and announced he would run for a first full term as party president. In the 2008 leadership election he faced Davorko Vidović and Dragan Kovačević, but emerged as the winner with almost 80 percent of the delegate vote.[citation needed]

First term as Leader of the Opposition (2007–2011)[edit]

With 56 seats won SDP emerged from the 2007 election as the second largest party in Parliament and the largest party that is not a part of the governing majority. This made Milanović the unofficial leader of the opposition. Milanović was very critical of the Sanader administration, especially concerning their handling of the economy and the fight against corruption.

In September 2008, Milanović made a highly publicized visit to Bleiburg to commemorate the victims of the Yugoslav Communists.[16] This made him the second leader of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia to visit the site, the first being Ivica Račan.

The 2009 local elections were held on 17 and 31 May and resulted with the Social Democrats making considerable gains in certain traditionally HDZ-leaning cities and constituencies, such as Dubrovnik, Šibenik, Trogir and Vukovar, as well as retaining such major traditionally SDP-leaning cities as Zagreb, Varaždin and Rijeka.[17]

On 1 July 2009, Ivo Sanader announced he was resigning the premiership and leaving his deputy Jadranka Kosor as prime minister. Parliament approved her and the new cabinet which made Kosor the first woman ever to be appointed prime minister.[18] Since late 2008, the SDP had been leading the polls, however by a narrow margin. After the sudden resignation of Sanader HDZ plummeted in the polls to their lowest level since 1999 when corruption scandals were rocking the party establishment.[19] Milanović insisted the resignation of the prime minister means that an early general election was necessary. The governing majority refused to dissolve Parliament and insisted that the Kosor cabinet would finish the remainder of its term.

In 2008 the country's accession to the European Union was deadlocked with the Slovenian blockade over a border dispute. Sanader and his Slovenian counterpart Borut Pahor were unable to settle their differences in the following months which meant Croatia's accession to the European Union was in a standstill. There was much speculation, since Sanader had not given a reason for his departure, whether the Slovenian blockade was the cause for his resignation. In the following months Kosor and Pahor met several times, trying to resolve the border dispute. The negotiations resulted in an agreement which led to the continuation of negotiations for the Croatian accession to the European Union. The solution was an Arbitration Agreement[20] which was signed in Stockholm on 4 November 2009, by both countries' prime ministers and the Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt.[21] The agreement required a two-thirds majority in Parliament for it to be approved. Milanović and most SDP MPs voted in favor of the agreement, however he criticized the Government and especially its former and present leaders, Sanader and Kosor, for wasting precious time since the arrangement with Slovenia could have been made a year earlier and Croatia would not have waited so long to continue with the accession process.[22]

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 hit most European countries hard, as well as Croatia. The crisis continued throughout the following years. Industry shed tens of thousands of jobs, and unemployment soared. Consumer spending reduced drastically compared to record 2007 levels, causing widespread problems in the trade as well as transport industries. The continuing declining standard resulted in a quick fall in both the prime minister's as well as government's support. Milanović was very critical of the Government's supposed slow response and inadequate measures that did little to revive the economy. The recession and high unemployment continued throughout 2011 resulting in many anti-government protests around the country.[23]

2011 parliamentary election[edit]

On 28 October MPs voted to dissolve Parliament.[24] President of the Republic Ivo Josipović agreed to a dissolution of Sabor on Monday, 31 October and scheduled the election, as previously suspected, for Sunday, 4 December 2011.[25] The 2011 parliamentary election saw SDP joining three other left-wing parties to create the media-dubbed Kukuriku coalition with Milanović at the helm. Kukuriku won the election with an absolute majority of 81 seats. The election was the first in which rival HDZ was not the leading individual party in Parliament.[26]

Prime Minister (2011–2016)[edit]

Milanović presented his cabinet to the Parliament on 23 December, 19 days after the election. The discussion resulted with 89 members, 81 Kukuriku and 8 national minority MPs, voting in favour of the Milanović cabinet.[27] The transition to power occurred the following evening when Jadranka Kosor welcomed Milanović to the government's official meeting place, Banski dvori, opposite the Sabor building on St. Mark's Square and handed him the necessary papers and documents.[28]

Taking office at the age of 45, Milanović became one of the youngest prime ministers since Croatia's independence.[29] In addition, his cabinet also became the youngest, with an average minister's age of 48.[30] Cabinet members came from three out of four parties of the winning coalition, leaving only the single-issue Croatian Party of Pensioners (HSU) without representation.[31] Milanović was reelected as president of the SDP in the 2012 leadership election as the only candidate.[32]

Domestic policy[edit]

The Milanović administration started its mandate by introducing several liberal reforms. During 2012, a Law on medically assisted fertilization was enacted, health education was introduced in all elementary and high schools, and Milanović announced further expansion of rights for same-sex couples.[33][34] During the 2011 elections the Kukuriku coalition promised to publish the registry of veterans of the Croatian War of Independence, which was done in December 2012.[35]

In the Trial of Gotovina et al, following an initial guilty verdict in April 2011, Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač were ultimately acquitted in November 2012. Milanović called the ruling "an important moment for Croatia", adding that "A huge weight has been lifted off my shoulders. I say thank you to them for surviving so long for the sake of Croatia."[36]

In September 2013 anti-Cyrillic protests started against the introduction of bilingual signs with Serbian Cyrillic alphabet in Vukovar. Milanović condemned them as "chauvinist violence", saying he will not take down signs in Cyrillic in Vukovar as the "rule of law must prevail".[37]

On 1 December 2013, a constitutional referendum was held in Croatia, its third referendum since becoming independent. The referendum, organized by the citizen initiative For the family of Željka Markić, proposed an amendment that would define marriage as a union between a man and a woman, thus creating a constitutional prohibition against same-sex marriage. Milanović opposed the proposal and told HRT that he would vote against it.[38] The government advised citizens to vote against it, but the referendum passed with 65% votes in favour, however, with voter turnout at only 38%. Milanović was unhappy that the referendum had taken place at all, saying "I think it did not make us any better, smarter or prettier."[39] He also said that the referendum does not change the existing definition of marriage according to Croatian laws. He further announced the upcoming enactment of the Law on Partnership, which will enable same-sex persons to form a lifetime partnership union, which would share the same rights as that of marriage proper, apart from the right of adoption.[40] On 12 December 2013 the Government passed the proposed Bill,[41] and the Parliament passed the Life Partnership Act in July 2014.[42]

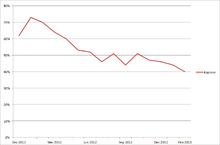

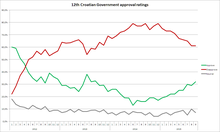

A bad economic situation weakened the originally strong public support for the Milanović government, which was demonstrated in the 2013 local elections.[43] In the first European Parliament elections in Croatia in 2013, SDP won 32% of the votes and five MEPs, one less than HDZ, the largest opposition party. The following year SDP won 29.9% in the 2014 European Parliament elections and four MEPs.[44] Milanović and his party gave support to Ivo Josipović in the presidential elections, which were won by Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović from the HDZ. Josipović later formed his own party, Forward Croatia-Progressive Alliance, instead of returning to the SDP.[45]

War veterans protest[edit]

Croatian war veterans started a protest in Zagreb in October 2014, calling for the resignation of Predrag Matić, war veterans minister, and a new constitutional law guaranteeing their rights. Milanović rejected their demands, saying that there is no reason to sack the minister and that he would not submit to ultimatums:[46]

My government has not, even by thought, act or omission, brought the human dignity of the Croatian defenders and the eternal significance of the Homeland War into question.[46]

The protest continued throughout 2015. In May 2015 it escalated when hundreds of veterans scuffled with the police in front of the government building. Milanović said that his government has not curbed their rights and that he is ready for talks, but will not be blackmailed. He accused the opposition party HDZ for manipulating with the veterans. Tomislav Karamarko, the president of HDZ, rejected the accusation.[47] Milanović met with the representatives of the protesting veterans in June, but the protest continued.[48]

On 4 August 2015, on the insistence of Milanović and the Defence Minister Ante Kotromanović, a military parade of the Croatian Armed Forces was held in Zagreb in honour of the Victory Day, celebrating the 20th anniversary of Operation Storm. Milanović thanked everyone who sacrificed their lives for Croatia's freedom. He also expressed his gratitude to Franjo Tuđman, first Croatian president, who led Croatia during the war.[49]

Croatia had every right to do everything that it could to stay alive and integral, it had the right not to get expelled from its home, it had the right not to serve as human shield to those who destroyed cities and burned down villages. Croatia today is not celebrating the war, it is not celebrating anyone's suffering or persecution, let this be clear to everyone who still don't understand. Croatia had done everything it could to avoid the war, it had offered peaceful solutions. And it was rejected. Croatia today celebrates freedom and peace and with a pure heart it celebrates victory, a turning point which put an end to an ugly, imposed and particularly caddish war

Economy[edit]

The Milanović administration adopted a number of reforms in taxation in order to cope with the difficult economic situation. It raised the standard Value-added tax from 23% to 25% and introduced new VAT rates for goods and services that were not previously taxed. It also cut social insurance contributions and public-sector wages.[31][50] In October the Financial Operations and Pre-Bankruptcy Settlements Act was passed, which allowed firms that were unable to pay their bills to stay open during the bankruptcy proceedings and restructure their debts.[51] Because of opposition by its coalition partner, HNS, property tax has not been expanded.[52]

The government succeeded in reducing the budget deficit to 5.3% in 2012,[53] but GDP contracted by 2.2% and public debt reached 69.2%.[54][55] Milanović's time in office has been marked by several cuts to Croatia's credit rating. On 14 December 2012 S&P cut the country's long term rating to BB+ and the short term rating to B.[56] On 1 February 2013, Moody's cut Croatia's credit rating from Baa3 to Ba1.[56]

Several major construction projects started in 2012, including a new passenger terminal on the Zagreb International Airport and a third block of the coal-fired Plomin Power Station. However, some projects have been suspended, including the Ombla hydroelectric power plant.[57] The government said that construction of the Pelješac Bridge was to start in spring 2016.[58] Milanović expressed his support for further oil and gas exploration and exploitation in the Adriatic Sea,[59] which is opposed by the opposition parties and environmental organizations.[60]

In November 2012, Minister of Economy and Deputy Prime Minister Radimir Čačić resigned and was replaced by Ivan Vrdoljak. In 2013 a new fiscalization law was introduced to control gray economy and minimize tax avoidance.[61] The government put focus on the shipbuilding industry and privatized state-owned shipyards by May 2013.[62] In order to service public debt, the government presented a project of monetization of Croatian highways in 2013 which would bring around 2.5 billion euros. Trade unions and civic associations rejected the proposal and called for a retraction of the decision.[63] A civic initiative called "We Are Not Giving Our Highways" gathered signatures for a highway referendum. Although the constitutional court ruled that a referendum on the subject was unconstitutional, the government announced that it was withdrawing the decision. Instead of the initial plan to lease the country's highways to foreign investors, the government will instead offer shares in them to Croatian citizens and pension funds.[64]

The Pension Insurance Act of January 2014 raised the statutory retirement age from 65 to 67 and early retirement age from 60 to 62.[65] The unemployment rate peaked in February 2014 at 22.7%,[66] but has since been steadily declining and reached its lowest rate in two years in August.[67] In May 2014 Milanović sacked the Finance Minister, Slavko Linić, over a property deal that he said had hurt the state budget and appointed Boris Lalovac on his place.[68] Changes in Personal Income Tax were introduced in 2015, the non-taxable part of income was raised, which resulted in a net salary increase for around one million people.[69]

In January 2015 the government decided to freeze exchange rates for Swiss francs for a year, after a rise in the franc that caused increasingly expensive loans for borrowers in that currency.[70] In August 2015 Milanović announced that Swiss franc loans will be converted into euro-denominated ones.[71]

GDP decreased in 2013 (-0.9%) and 2014 (-0,4%), but in the 4th quarter of 2014 real GDP growth reached 0.3% for the first time since 2011.[54] It was announced on 28 August 2015 that the economy had grown by 1.2% for a third consecutive quarter which marked Croatia's exit from a six-year economic recession.[72] The budget deficit decreased in 2015 to 3.2% of GDP, down from 5.5% in 2014, and public debt was at 86.7% of GDP, the lowest debt growth rate since the introduction of the ESA 2010 methodology.[73]

Foreign policy[edit]

Milanović's foreign policy was initially concentrated on the accession of Croatia to the European Union. On 22 January 2012, an EU accession referendum was held, with 66.25% voting in favour and 33.13% against. About 47% of eligible voters took part in the referendum.[31] On 11 March 2013, Milanović signed the Memorandum of Agreement with Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Janša, regarding the issue of Ljubljanska Banka, which closed down in 1991 without reimbursing its Croatian depositors. Croatia agreed to suspend a lawsuit against the bank and its successor, while Slovenia pledged to ratify Croatia's EU Accession Treaty.[74] Slovenia ratified Croatia's accession bid on 2 April 2013.[75] After all 27 member states signed the EU accession treaty, on 1 July 2013, Croatia joined the European Union, becoming the 28th member state.[76]

On 27 February 2012 Milanović visited Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was his first travel to a foreign country since he became prime minister.[77] On the following day he visited Široki Brijeg and Mostar, where he met with members of the Croatian National Assembly, a political organisation of the Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Milanović said that all he is asking for Croats in that country is a fair deal and added that Croatia will support the Accession of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the European Union.[78]

Due to the ongoing civil war in Syria, in February 2012 Milanović called on Croatian companies working in Syria to withdraw from the country.[79] On 18 January 2013 Croatian Foreign Ministry declared that Croatia, as well as the entire European Union, recognizes the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces as the only "legitimate representatives of the aspirations of the Syrian people".[80][81] In February 2013 Milanović announced that Croatia is withdrawing its troops from the Golan Heights that are participating in the UN's peacekeeping mission after it was reported that Croatia sold their old weapons to the Syrian opposition.[82]

When demonstrations and riots started in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2014, Milanović visited Mostar, a city with a Croat majority, where the seat of HDZ BiH was damaged in the riots. Sarajevo criticized his move, saying he should have visited the capital first. Milanović later called the protest quasi-civic on ethnic and religious vertical.[83] The Croatian Government refused to accept indictments from Sarajevo labeled as political due to unacceptable claims about the character of the Croat–Bosniak War.[84]

On 22 July 2015 a major scandal occurred during the arbitration procedure of the Croatian–Slovenian border dispute, when it was discovered that the Slovenian representative has been lobbying other judges to rule in Slovenia's favor. Three days later Milanović announced the withdrawal of Croatia from arbitration after a meeting with the leaders of parliamentary groups.[85]

European migrant crisis[edit]

Beginning on 16 September 2015, migrants and refugees from the Middle East, South Asia and Africa began entering Croatia from Serbia in large numbers[86] after the construction of the Hungary-Serbia barrier. On 17 September Croatia closed its border with Serbia.[87] After initial efforts to register all migrant entrances into Croatia, registration ceased on 18 September and migrants began to be transported toward Slovenia and Hungary. By 23 September 2015 over 40,000 had entered Croatia from Serbia, with main acceptance centers set up in Opatovac and Zagreb,[88] while migrants were also held in Beli Manastir, Ilača, Tovarnik, Ježevo and Sisak.[89] Milanović criticized Serbia for sending migrants only towards the Croatian border, while sparing Hungary and Romania[90] and stated that his country "will not become a migrant hotspot".[91] Tensions escalated between Serbia and Croatia and on 24 September Serbia banned imports from Croatia to protest against Croatia's decision to close the border to cargo, while Croatia responded by banning all Serbian-registered vehicles from entering the country.[92] On 25 September Croatia lifted the blockade on its border and Serbia lifted its ban on imports from Croatia, but Milanović said that he is ready to block the border again if necessary.[93] With winter approaching a new, more permanent refugee acceptance center was built in Slavonski Brod in late 2015.[citation needed]

2015 Parliamentary election[edit]

For the 2015 parliamentary election the Kukuriku Coalition changed its name to Croatia is Growing. It consists of three out of four original members: the Social Democratic Party, Croatian People's Party – Liberal Democrats (HNS-LD), Croatian Party of Pensioners (HSU), as well as three new ones: Croatian Labourists – Labour Party, Authentic Croatian Peasant Party (A-HSS) and Zagorje Party. Istrian Democratic Assembly left the coalition. The campaign of the Coalition, led by Milanović, was based on rhetoric against austerity measures and emphasizing the government's policies during its mandate.[94]

After 76 days of negotiations, the Patriotic Coalition and the Bridge of Independent Lists party formed the 13th Croatian Government with Tihomir Orešković as the new prime minister. Milanović formally handed over office to Orešković in the late hours of 22 January 2016, after a lengthy parliamentary debate on the new government's program and the subsequent vote of confidence.[citation needed]

Second term as Leader of the Opposition (2016)[edit]

On 2 April 2016, elections were held for the party's leadership. Milanović's opposing candidate was Zlatko Komadina, the prefect of Primorje-Gorski Kotar County, who advocated for a "much more social democratic" SDP.[95] Milanović was again re-elected president of SDP for the next four years.[96]

2016 parliamentary election[edit]

In July 2016, SDP, HNS-LD and HSU formed the People's Coalition (Croatian: Narodna koalicija) for the 2016 parliamentary election. They were joined by the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS), while the Croatian Labourists left the coalition.[97]

Leaked taped conversations from a meeting with representatives of veterans association, published on 24 and 25 August 2016 by Jutarnji list, in which Milanović made controversial statements against the neighboring countries of Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, have caused criticism.[98][99] While commenting on Serbia's accession to the EU and their law on universal jurisdiction for war crimes prosecution on the whole territory of former Yugoslavia, Milanović stated that the Serbian government was acting arrogantly, and that he was willing to block Serbia's EU accession negotiations and also adopt a special law which would allow Croatia to prosecute Serbian citizens who committed war crimes in Kosovo, adding that "Serbs want to be rulers of the Balkans, but are actually a handful of misery".[100] While commenting on Bosnia and Herzegovina, Milanović stated that he wasn't "thrilled with the situation there" and complained that "there was no one he could talk to in Sarajevo", adding that he would like for Bosnia and Herzegovina to enter the EU even without all the preconditions being met, since "it's a country without law and order".[101] In addition, he stated that he did not care about Za dom spremni salute but urged veterans not to use it because it is harmful to Croatia.[102] Milanović's rhetoric during the 2016 electoral campaign was described by some observers as populist.[103][104]

The HDZ won a majority of seats in the parliament and formed a governing majority with Most, with HDZ leader Andrej Plenković becoming the new Prime Minister. Milanović announced that he would not run for another term as SDP president.[105] On 26 November he was succeeded by Davor Bernardić as the president of SDP.[106]

Break from politics[edit]

After leaving politics, Milanović entered the consulting business and founded a consulting firm called EuroAlba Advisory.[107] Since 2017, he was an advisor to Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama,[108] and president of the Diplomatic Council of the Dag Hammarskjöld University College of International Relations and Diplomacy.[109]

2019 presidential campaign[edit]

On 17 June 2019, Milanović confirmed that he will be running in the country's upcoming presidential election as SDP's candidate, with the campaign slogan "A president with character".[110] While announcing his candidacy, Milanović said that he wanted to be the "president of a modern, progressive, inquisitive and open Croatia".[111] The SDP main committee, as well as the HSS presidency, gave support to Milanović's bid for president.[112][113] He was subsequently endorsed by several centre-left and centrist parties, including the HSU, PGS, NS-R, Democrats, IDS, HL, SU, Glas, MDS, SNAGA, and ZS.[114][115]

The first round of the election took place on 22 December 2019, with Milanović winning a plurality of 29.55% of the vote, ahead of Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, who received 26.65% of the vote.[116] Miroslav Škoro, who was running as an independent candidate, narrowly failed to reach the run-off election, managing to attract the support of 24.45% of voters.[116] Therefore, this election marked the first time in Croatian history that the incumbent president did not receive the highest number of votes in the first round. Furthermore, Milanović attained both the lowest number of votes (562,779) and the lowest percentage of the vote of any winning candidate in the first round of a presidential election.[117] Milanović received a plurality of the vote in Croatia's three largest cities: 33.02% in Zagreb, 30.79% in Split and 41.87% in Rijeka, and finished second (25.61%) in the fourth largest city, Osijek, which was won by Škoro (33.33%).[118]

A run-off election took place between Milanović and Grabar-Kitarović on 5 January 2020. Milanović won by a margin of close to 105,000 votes, thereby becoming the 5th President of Croatia since independence and the second president to have been officially nominated by the Social Democratic Party, after Ivo Josipović (2010–2015).[119]

Since his electoral victory, the newly elected president Zoran Milanović has made his first public appearance at an official event in Rijeka. There he attended the inaugural ceremony of Rijeka as the European Capital of Culture 2020.[120] He met with the mayor Vojko Obersnel, commended the artists, the day-long programme and the opening ceremony.[121] Milanović also praised the founders of punk rock in Rijeka and its 44-year-old tradition, stating that, "By the time when the Paraf were having their first concert, Sid Vicious hadn’t been singing in the Sex Pistols yet. These facts are of crucial importance regarding the cultural map of Europe".[122]

Presidency (2020–present)[edit]

The inauguration of Milanović as the 5th president of Croatia took place on 18 February 2020. This was the first time that a presidential inauguration ceremony in Croatia was not held at St. Mark's Square in the city center of Zagreb, where the parliament and government buildings are located. Instead, Milanović decided to forgo the usual pomp of the ceremony by inviting merely some 40 guests, including state officials, former presidents, his family and members of his campaign team.[123] This was also the first time that party leaders, diplomats and church dignitaries did not attend a presidential inauguration.[124] The ceremony began with the performance of the national anthem by renowned Croatian pop and jazz diva Josipa Lisac, accompanied by pianist Zvjezdan Ružić, whose alternative rendition of Croatia's national anthem struck a different tone to the national anthem's usual sombre, bombastic delivery.[125][126][127] This caused a lot of positive comments and negative reactions, which resulted in an unprecedented public debate about the national anthem and artistic freedom.[128][129]

On 24 February 2020, Milanović strongly condemned the burning of an effigy showing a same-sex couple with their child at a festival in Imotski, describing the incident as an "inhumane, totally unacceptable act", demanded an apology from the organizers of the event and stated that they "deserve the strongest condemnation of the public because hatred for others, intolerance and inhumanity are not and will not be a Croatian tradition".[130][131] He also demanded a reaction from the relevant institutions especially as the event was observed by many children who could witness the spreading of hatred and inciting to violence.[130]

Milanović made his first trip abroad as president on 27 February 2020 to Otočec ob Krki, Slovenia, where he met with president Borut Pahor. The two of them firmly concluded that they would do everything to improve and make the relations between the two countries excellent, pointing out that they had known each other for over 16 years. They also discussed about the border issue between the two countries, Croatian accession to the Schengen Area and about the border controls implemented by the Croatian government due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Milanović also addressed the European perspective of Montenegro, Albania and North Macedonia.[132]

During the summer Milanović visited Montenegro and met with president Milo Đukanović. He also canceled his planned trip to Russia, where president Vladimir Putin invited him to attend the 2020 Victory Day parade. In September and October, he got involved in a verbal confrontation with a number of prominent Croatian politicians, political analysts and journalists, including the prime minister Andrej Plenković.[133] He voiced his opposition to lockdown and curfew, as he said he would arrest and put in a police van those wanting curfew and lockdown.[134]

In January 2021, Milanović refused to participate in a ceremony commemorating the 1993 Operation Maslenica because the Croatian Defence Forces′ symbols were to be displayed.[135] In September 2021, he publicly voiced his opinion that Bunjevci are Croatians. The national council of Bunjevci responded harshly to his statements, stating that Bunjevci had been living in Subotica for 350 years and that the difference between Bunjevci and Croats was clearly attested by historical sources.[136][137]

In November 2021, Austria's foreign ministry summoned the Croatian ambassador in Vienna, Daniel Glunčić, to give an explanation, after Milanović compared the lockdown in Austria to the methods employed in the era of Nazism.[138]

War in Ukraine[edit]

In December 2021, Milanović criticised prime minister Plenković's visit to Ukraine made at the start of a new escalation of the crisis over Ukraine calling it "plain charlatanism".[139][140] The prime minister responded by saying that the government sought to maintain good relations with Russia too.[140]

Harsh reaction from Ukraine's government followed Milanović's statements made on 25 January 2022 about Ukraine being not fit to join NATO as well the country being corrupt and Russia deserving to be given a way to have its security demands met.[141][142][143] Milanović also referred to the 2014 Maidan Revolution in Ukraine as a "coup d'état".[144][145] The foreign ministry of Ukraine summoned Croatian ambassador Anica Djamić, whereafter the ministry issued a comment that said, "[...] Zoran Milanović's statements retransmit Russian propaganda narratives, do not correspond to Croatia's consistent official position in support of Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity, harm bilateral relations and undermine unity within the EU and NATO in the face of current security threats in Europe. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine demands a public refutation of these insulting statements by the President of Croatia, as well as non-repetition in the future."[146][147] The same day, he was included in the blacklist of Myrotvorets.[148] Russia's pro-government media outlets gave Milanović's pronouncements much publicity, presenting them as a sign of a split in the ranks of the EU and NATO and predicting that other EU leaders would follow suit.[149] Croatia's prime minister Plenković reacted by saying that on hearing Milanović's statements he thought it was being said "by some Russian official"; he also offered apologies to Ukraine and reiterated that Croatia supported Ukraine's territorial integrity.[150] In an interview with the RTL television network shortly after, Milanović refused to apologise and re-affirmed his stance on Ukraine and went on to say that he thought that prime minister Andrej Plenković "behaved like an agent of Ukraine".[151][152] On 1 March 2022, Milanović stated: "one has to be concerned when Ukraine threatens to use nuclear weapons, or when Russia threatens to use nuclear weapons."[153]

On 1 February 2022, as the UK defence secretary Ben Wallace was in Zagreb for a meeting with his Croatian counterpart, Mario Banožić, to discuss the security situation caused by the crisis over Ukraine, Milanović told the press he thought Britain was "misleading Ukraine, inciting it, and holding it hostage to the relationship between London, which ha[d] become a second-order power, and Washington"; he also said Ukraine would "not make itself happy if it listen[ed] to London" and voiced his opinion that the EU could not enjoy stability without settlement with Russia.[154][155][156] Shortly after, former Russian ambassador to Croatia Anvar Azimov welcomed "the reasonable statements of president Zoran Milanović about Ukraine", while Croatian weekly Globus opined that Milanović proved to be the only statesman in the EU and NATO, who "so openly demonstrated his acceptance of Russia, relativised its actions, and criticised America, Britain and other NATO allies for the current tensions".[157][158] When being asked by journalists about Bucha massacre, Milanović responded: That is far away, I know nothing about that. The Russians withdrew. What was found there, who found it, from Croatian experience, don't ask me about that, be careful." On the same occasion, he said that Ukraine isn't a democratic state "otherwise they would [already] start negotiations with the EU or had some status".[159] In June Milanović again commented on the war in Ukraine by saying: "Zelenskyy's words lead to defeat, once Russian boot arrives somewhere, it never leaves. It is a powerful military force. Russia is not like us, they are not a democracy. As an enemy, they are indestructible."[160] In September 2022, Milanović characterised the EU's Ukraine policy as "stupid" and not being in the interest of Croatia, nor Germany. He went on to say: "We're currently watching Russia emaciate Ukraine with a very small number of soldiers". He added that the West had for eight years failed to have Ukraine respect the Minsk agreements.[161]

In the aftermath of Tu-141 drone crash in Zagreb, Milanović issued the order to ban NATO's aircraft flights over Zagreb and other Croatian cities, stating that the flights "disturb the citizens". By doing so, he continued his conflict with prime minister Plenković, who said that these flights are supposed to send the message of "strategic partnership and safety of Croatian citizens".[162] After EU announced the possibility of training Ukrainian troops on its territory, including in Croatia, Milanović announced he was blocking this decision because, according to him that would bring the war to Croatia.[163][164] In late January 2023, Milanović said: "from 2014 to 2022 we observed how someone provoked Russia, with intent of instigating this war. [...] Now we talk about tanks. We will send all German tanks there, as the Russian ones burned. The same destiny awaits the others..."[165] In March 2023 Milanović gave a statement saying that Croatian donation of Mi-8 transport helicopters to Ukraine: "will lead to mass bloodshed, mass casualties and it extends the war"[166] In June same year, he claimed that: "Ustaše were gentlemen in comparison with those who fought by the salute "slava Ukraini".[167]

Finnish and Swedish NATO accession[edit]

In April 2022, Milanović suggested blocking Finnish and Swedish accession to NATO until the electoral law in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which would allow Bosniaks the option of electing a Croat member of the Presidency and Croat representatives in the House of Peoples of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was changed. He went on to say that he would label every MP in Croatian Sabor who refused to vote against expansion of NATO as a national traitor.[168] On 28 April 2022, Foreign Minister Gordan Grlić-Radman announced that Croatia supports Finland and Sweden's applications for membership in NATO.[169] In May 2022, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan opposed Finland and Sweden's NATO membership,[170] and in June 2022, Erdoğan withdrew the objections of the two countries membership process.[171] After Finland's foreign minister Pekka Haavisto stated that his country was shocked by Milanović's statements, Milanović responded by saying: "Welcome to the club, mister foreign minister. We have been shocked for several years already by your ignorance and rudeness".[172] However, the Finnish Minister for European Affairs and Ownership Steering Tytti Tuppurainen later commented that, although the citizens of Finland were confused by Milanović's statements, Finland understood the Croatian concern about the reforms of the electoral law in Bosnia and Herzegovina and that Finland supported the international efforts regarding the changes of the electoral law.[173] His prior comments notwithstanding, Milanović did not veto Finnish and Swedish NATO accession at the 2022 NATO Madrid summit.[174]

War in Gaza[edit]

In October 2023, he criticized Israel's retaliatory strikes on the Gaza Strip, saying "I condemned [Hamas’] murders, I even expressed disgust and abhorrence, but the right to defense does not include the right to revenge and the killing of civilians."[175]

2024 parliamentary election[edit]

On 15 March 2024, Milanović announced his candidacy for the office of Prime Minister on the SDP list in the parliamentary election.[176][177][178]

Personal life[edit]

Milanović is a fan of the Croatian football club Hajduk Split.[179][180]

Honours[edit]

| Ribbon | Distinction | Country | Date | Location | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of Merit with a collar | 12 December 2022 | Santiago | Highest civil decoration in Chile | [181] |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Milanović was elected president under the nomination of the SDP. However, as per article 96 of the Constitution, he was required to resign his party membership prior to taking office.[1]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Milanović i službeno prestao biti član SDP-a". www.tportal.hr (in Croatian). Tportal. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "zòra" and "mȉo". Hrvatski jezični portal (in Croatian). Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Milanović – Od fakina iz kvarta do šefa Banskih dvora". Večernji list. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b c "Zoran Milanović: Moj deda je bio ustaša!". Novosti.

- ^ "Milanović se nasmijao na konstataciju novinara o broju glasova iz BiH | N1 BA". ba.n1info.com. 7 January 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Bajruši, Robert (14 August 2016). "Tko je Milanovićev djed ustaša kojeg je tek sada otkrio".

- ^ PSD (5 January 2022). "Iako joj je sin predsjednik, Đurđica Milanović uspješno bježi od očiju javnosti. Djetinjstvo joj nije bilo lako, a godinama je od Zorana krila veliku obiteljsku tajnu". Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "UMRO JE BRAT ZORANA MILANOVIĆA Nakon duge i teške bolesti preminuo je u 49. godini". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 21 September 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Javno – Hrvatska Archived 3 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, javno.com; accessed 15 April 2015.

- ^ Zoran Milanović profile Archived 24 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, zivotopis.hr; accessed 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Sanja Milanović: 17 godina uz Zorana Milanovića" (in Croatian). 29 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ "Premijerova supruga samozatajna je liječnica i majka". Večernji.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Milanović obećao ostavku ako ne pobijedi Sanadera". 24sata.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Zrinjski, Marijana; Jurić, Goran (2 June 2007). "Uskoro rezultati izbora za predsjednika SDP-a" [SDP presidency election results to follow soon] (in Croatian). Nacional (weekly). Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Zoran Milanović novi predsjednik SDP-a!". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 2 June 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Milanović na Bleiburgu: "Ja sam tu zbog žrtava, a ne zbog propalih režima", Dnevnik.hr; accessed 15 April 2015.

- ^ Čizmić, Martina (15 June 2009). "Ponovljeni izbori: SDP dobio Šibenik i Trogir" [Repeated vote: SDP wins Šibenik and Trogir]. Nacional (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ "Croatia's PM Sanader resigns, quits politics". Reuters. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ "Nikad veća razlika: SDP 'potukao' HDZ". Nova TV (in Croatian). 1 August 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ "Premiers Kosor, Pahor say two countries at watershed, politics must find solutions". Croatian Government. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "Croatia, Slovenia open new chapter in their relations, PMs say". Croatian Government. 4 November 2009. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "Sabor izglasao Sporazum o arbitraži, SDP 'aktivno suzdržan'", Dnevnik.hr; accessed 15 April 2015.

- ^ Rastrgali zastavu HDZ-a, zapalili SDP-ovu i EU-a Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, novilist.hr; accessed 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Pogledajte sve snimke sa suđenja Sanaderu". Dnevnik.hr. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Predsjednik Josipović raspisao izbore!". Odluka2011.dnevnik.hr. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Sustainable Governance Indicators - 2015 Croatia Report, p. 2

- ^ "Pogledajte kako je izglasano povjerenje Vladi!", rtl.hr; accessed 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Kosor s velikim brošem HDZ-a Milanoviću predala vlast: Idemo probati biti uspješni", slobodnadalmacija.hr; accessed 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Pogrešna računica: Milanović nije najmlađi hrvatski premijer". Doznajemo.com (in Croatian). Zagreb. 24 December 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Toma, Ivanka (22 December 2011). "Milanovićevih 21 - Najmlađi premijer, najmlađa vlada". Večernji list (in Croatian). Zagreb. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ a b c "Croatia in 2012". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "SDP sutra bira vodstvo - Milanović jedini kandidat". slobodnadalmacija.hr. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Milanović: Gay parovima trebamo dati prava kao u Španjolskoj, zbog toga nitko neće ništa izgubiti". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 11 May 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ Rukavina Kovačević, Ksenija (27 July 2013). "Građanski Odgoj I Obrazovanje U Školi – Potreba Ili Uvjet?". Riječki Teološki Časopis. 41 (1). Hrcak.srce.hr: 101–136. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Croatia Publishes List of War Veterans". balkaninsight.com. 20 December 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Generals' war crime convictions overturned". stuff.co.nz. 17 November 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Anti-Serbian language protests highlight Croatia tensions". The Sun (Malaysia). 6 September 2013. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Croatia to hold referendum on same-sex marriage ban BBC News, 8 November 2013

- ^ "Croatian Government to Pursue Law Allowing Civil Unions for Gay Couples". The New York Times. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Gayevi će se vjenčavati, samo se njihova veza neće moći zvati brakom [Gays will be able to get married, but their relationship can not be called marriage], archived from the original on 12 April 2016, retrieved 27 October 2015

- ^ Foto: Patrik Macek/PIXSELL. "Milanović: Veslom smo gurali Jakovinu da ide u Bali" (in Croatian). Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "Povijesna Odluka U Saboru Istospolni će parovi od rujna imati ista prava kao i bračni partneri". jutarnji.hr. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Sustainable Governance Indicators - 2015 Croatia Report, p. 4

- ^ "Results of the 2014 European elections - Results by country - Croatia - European Parliament". Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Josipovic to Form New Left Party in Croatia". balkaninsight.com. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Croatia PM Rejects Protesting Veterans' Demands". balkaninsight.com. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatian PM says opposition manipulating war veterans' protest". reuters.com. 29 May 2015. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Protesting veterans, PM and ministers again at sitting table". dalje.com. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Milanovic says Croatia not celebrating war but freedom and peace". dalje.com. 29 May 2015. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Sustainable Governance Indicators - 2014 Croatia Report, p. 7

- ^ "Fina distraint orders prove to be efficient". limun.hr. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Sustainable Governance Indicators - 2015 Croatia Report, p. 8

- ^ "Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Rating: Croatia Credit Rating 2023 | countryeconomy.com". countryeconomy.com.

- ^ "Zmajlović potvrdio: Vlada je odbila HEP-ov zahtjev za gradnju hidroelektrane Ombla". vijesti.rtl.hr. 25 July 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatia: Delayed bridge bypassing Bosnia goes ahead". BBC News. BBC Monitoring. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Adriatic Driling: Milanović Supports Further Exploration of Hydrocarbon Reserves in the Adriatic Sea". total-croatia-news.com. 16 August 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "HDZ against HPB's privatisation, oil rigs in Adriatic". dalje.com. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Grey economy on the way out in Croatia". croatiaweek.com. 1 January 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatia plans to wrap up privatization of shipyards by end-May – fin min". wire.seenews.com. 21 January 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatian Government Faces Demands to Retract its Decision on Motorway Concessions". oneworldsee.org. 19 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatia to Offer Shares in Highways to Citizens". balkaninsight.com. 24 April 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Sustainable Governance Indicators - 2015 Croatia Report, p. 13

- ^ "ALARMANTNE BROJKE Stopa nezaposlenosti u veljači najviša u posljednjih 12 godina, a Mrsić je zadovoljan". Jutarnji list. 21 March 2014.

- ^ "Nezaposlenost na najnižoj razini u dvije godine". Novi list. 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Croatian PM sacks finance minister over property purchase". wire.seenews.com. 6 May 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Personal Income Tax (Croatia)". ecovis.com. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatia Freezes Swiss Franc Exchange Rate". balkaninsight.com. 20 January 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatia to convert Swiss franc loans into euros". reuters.com. 25 August 2015. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "RAST IZNAD SVIH OČEKIVANJA Hrvatsko gospodarstvo u drugom tromjesečju ove godine poraslo 1,2 posto, znatno više od prethodnog kvartala". Jutarnji.hr. 28 August 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Croatia's 2015 general government deficit at 3.2%, public debt at 86.7% of GDP". EBL News. 21 April 2016. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Slovenia and Croatia Signed LB Memorandum". The Slovenia Times. 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Slovenia backs Croatia's EU entry after bank dispute set aside". Reuters. 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Croatia celebrates on joining EU". BBC. 1 July 2013.

- ^ "Premijer Milanović u Sarajevu". Croatian Radiotelevision. 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Milanović u Mostaru: Posjetio SKB Mostar i Sveučilište, održao predavanje studentima". bljesak.info. 28 February 2012.

- ^ Kuzmanovic, Jasmina (23 February 2012). "Croatian Companies Should Exit Syria, Premier Milanovic Says". Businessweek. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "RH priznala sirijsku oporbu kao legitimnog predstavnika naroda - Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ I.M. (18 January 2013). "Hrvatska priznala sirijsku oporbu kao jedinu legitimnu vlast u Siriji - Vijesti". Index.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Zbog NY Timesa Hrvatska povlači svoje vojnike s Golanske visoravni". Večernji list (in Croatian). 28 February 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Milanović u Mostaru: 'Prosvjedi se ne bi dogodili da je EU znala što želi u BiH'". dnevnik.hr. 9 February 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Bosnia says Croatia free to decide on indictments". dalje.com. 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Milanovic: Croatia is withdrawing from arbitration". Dalje. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ "U Hrvatsku stiglo 1300 izbjeglica: "Trebamo pomoć, ne možemo se nositi s desecima tisuća ljudi"". Index.hr. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Migrant crisis: Croatia closes border crossings with Serbia". BBC News. 18 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Na Kubi proizvedena "Julija" - prva cigara za žene - Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "FOTO, VIDEO: SITUACIJA SVE TEŽA Drama u Slavoniji: Vlaka još uvijek nema, a izbjeglice nemaju ni kapi vode! U Dugavama azilant gađao ciglom fotoreportera, s balkona hotela viču: 'Sloboda'". Jutarnji.hr. 17 September 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Croatia PM urges Serbia to redirect migrants to ease burden". Channel NewsAsia. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Matthew Weaver and agencies (18 September 2015). "Croatia 'will not become a migrant hotspot' says prime minister | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Tensions between Croatia and Serbia rise over refugees". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Croatia lifts border blockade with Serbia". reuters.com. 25 September 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "News Analysis: Third option in Croatian elections to lower percentages won by major parties". xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Komadina: It's time for a democratic and modern SDP". EBL News. 16 January 2016. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Milanovic re-elected SDP leader". EBL News. 2 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "SDP to run in coalition with HNS, HSS and HSU". EBL News. 9 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Leaked Audiotapes of Former PM and SDP Chief Milanović Cause Controversy in West Balkans". 25 August 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "Poslušajte kako je tekao jednosatni sastanak na Iblerovom trgu". Jutarnji list. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ Hanza Media (24 August 2016). "MILANOVIĆ O SRBIMA 'Žele biti gospodari Balkana, a zapravo su šaka jada' -Jutarnji List". Jutarnji.hr. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ "Milanović: BiH nije država | Al Jazeera Balkans" (in Bosnian). Balkans.aljazeera.net. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Hanza Media (24 August 2016). "Milanović ponudio braniteljima: 'Želite li da vam ostavim Tomu Medveda?' -Jutarnji List". Jutarnji list. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Stojić, Marko (2017). Party Responses to the EU in the Western Balkans: Transformation, Opposition or Defiance?. Springer. p. 70. ISBN 978-3319595634.

- ^ "Croatia vote overshadowed by nationalist rhetoric". BBC News. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Zoran Milanović Will Not Run for Another Term as SDP President". Total Croatia News. 12 September 2016.

- ^ "New SDP leader to advocate society of equal opportunity". EBL News. 27 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Former Prime Minister Milanović Starts a Business". Total Croatia News. 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Former Prime Minister Milanović Advising Albanian Government". Total Croatia News. 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Milanović dobio novi posao, radit će u Visokoj školi diplomacije". index.hr. 17 November 2017.

- ^ "Milanovic confirms running for president on his Facebook profile". N1. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Zoran Milanović Launches His Presidential Campaign". Total Croatia News. 18 June 2019.

- ^ "SDP main committee supports Zoran Milanovic's presidential bid". N1. 6 July 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "HSS supports Milanovic in presidential race". N1. 16 July 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "ŠIROKA KOLINDINA POTPORA S PROŠLIH IZBORA SVELA SE SAMO NA HDZ Završen ciklus grupiranja stranaka oko kandidata: Analiziramo tko je najbolje prošao..." Jutarnji list. 30 September 2019.

- ^ "MDS daje podršku kandidaturi Zorana Milanovića za predsjednika Republike Hrvatske — eMedjimurje.hr". emedjimurje.rtl.hr. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Zoran Milanović relativni pobjednik izbora, u drugi krug i Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović". novilist.hr. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Službene stranice Državnog izbornog povjerenstva Republike Hrvatske - Naslovna". izbori.hr. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Službene stranice Državnog izbornog povjerenstva Republike Hrvatske - Naslovna". izbori.hr. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Croatia elects centre-left challenger as president". 6 January 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "PM says gov't strongly supported Rijeka as European Capital of Culture project". 7 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Milanović: Friends from Ljubljana Are Our Most Natural Allies". 2 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Milanović: U vrijeme kad su Parafi imali prvi koncert Sid Vicious još nije pjevao u Sex Pistolsima" (in Croatian). 1 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Zoran Milanovic inaugurated as Croatian president". 27 February 2020. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Zoran Milanovic inaugurated as Croatia's fifth president in low-key ceremony". 18 February 2020. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Josipa Lisac pjeva himnu uz klavirsku pratnju Zvjezdana Ružića, na inauguraciji Zorana Milanovića". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Singer Josipa Lisac sued for 'mocking' Croatian national anthem". 21 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Croatian singer faces criminal charges for 'mocking' national anthem". 21 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

"...While some find it deep, artistic and special, others see it as mockery as performance not worth of the National Anthem." - ^ "Croatian singer Josipa Lisac gets sued for her performance of the National Anthem". 20 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

"...While some find it deep, artistic and special, others see it as mockery as performance not worth of the National Anthem." - ^ "JOSIPA LISAC IZVEDBOM 'LIJEPE NAŠE' IZAZVALA RASPRAVE: 'To nije moja himna…', kažu jedni, drugi uzvraćaju: 'Kad sluh oštrite na narodnjacima'" (in Croatian). 18 February 2020. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Outrage after effigy of same-sex couple and child burned at festival in Croatia". 26 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Croatia's president condemns burning of gay couple effigy". 24 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Predsjednici Hrvatske i Slovenije žele bolje odnose unatoč "problemčićima"" (in Croatian). 27 February 2020. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Milanović sada napada GONG, a evo kako ga je hvalio kao premijer". N1 HR (in Croatian). 7 October 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Milanović: One koji spominju uvođenje policijskog sata treba strpati u maricu. Ne želim za to ni čuti. Što da stanemo kao kad je umro Tito u 15.05?". Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). 30 October 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Milanović napustio protokol za Maslenicu zbog majica s natpisom 'za dom spremni'". Večernji List. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Nacionalni savet Bunjevaca Milanoviću: Čuvamo posebnost našeg identiteta". 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Bunjevački nacionalni savet - Saopštenje Nacionalnog savita bunjevačke nacionalne manjine povodom izjave Zorana Milanovića, pridsidnika Republike Hrvatske".

- ^ "Zbog izjava Milanovića oko austrijskih kovid mera ambasador pozvan na razgovor". 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Milanović kritizirao Plenkovićev posjet Kijevu: "Obično šarlatanstvo. Zbrisat će u Bruxelles ako zagusti"". Nacional. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ a b "PM: Croatia's relationship with Ukraine is in no way against Russia". N1. 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Croatia to recall all troops from NATO in case of Russia-Ukraine conflict". TASS. 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "VIDEO Milanović: Ja sam zapovjednik vojske, hrvatski vojnici neće ići u Ukrajinu" (in Croatian). Index.hr. 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Milanovic: Ukraine does not belong in NATO". N1. 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Croatia PM apologizes to Ukrainians for president's statement". Ukrinform. 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Croatia sows confusion with threat to pull NATO troops over Ukraine crisis". Politico. 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Comment of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine on the statements of President of Croatia Zoran Milanović". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine summons Croatian ambassador to Kyiv over Milanovic's remarks". N1. 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Президент Хорватии попал в базу "Миротворца" за "антиукраинскую пропаганду"" (in Russian). Kommersant. 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Zoran Milanović, novi ruski heroj: 'Konačno je netko rekao ono što svi u EU misle!'" (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "VIDEO Plenković o Milanovićevoj izjavi o Ukrajini i Rusiji: Ispričavam se Ukrajincima" (in Croatian). Index.hr. 25 January 2022.

- ^ "President: I am neither enemy of Ukraine nor friend to Russia". N1. 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Milanović za RTL: 'Neka se Plenković ispričava. On se ponaša kao ukrajinski agent, a ja kao hrvatski predsjednik" (in Croatian). RTL television network. 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Milanović: Ukrajinci nisu dali dobar otpor, a nama su naši problemi veći od njihovih". www.index.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "President Milanovic accuses the West of 'warmongering' over Ukraine crisis". N1. 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Croat president slams UK, demands agreement with Russia". Euractiv. 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Milanović ne da vojnicima u Ukrajinu, vlast optužio za korupciju: "Ako je pola toga istina, to je razlog za pad Vlade"" (in Croatian). Dnevnik.hr. 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Azimov za Večernji: 'Rat Rusije protiv Ukrajine potpuni je blef, a SAD treba prihvatiti jednu činjenicu'" (in Croatian). Večernji list. 8 February 2022., # 20820, p.9.

- ^ Putinov najdraži predsjednik: Kako je Milanović približio Pantovčak Kremlju i šokirao Bruxelles // Globus, 9 February 2022, # 1547, p. 13.

- ^ "VIDEO Milanović: Ukrajina nije demokratska država". www.index.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "VIDEO Milanović: Ovo što Zelenskij radi vodi u poraz, Rusija je neuništiva". www.index.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Đečević, Jasmin (1 September 2022). "Milanović: Politika EU prema ratu u Ukrajini je glupa. Pa pogledajte što je Tuđman bio spreman napraviti". Novi list. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ "Jutarnji list - Milanović izdao zapovijed Hranju: 'Najstrože zabranjujem prelete vojnih aviona iznad Zagreba i svih drugih gradova!'". www.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 15 March 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Telegram.hr. "Milanović će, kaže, blokirati obuku ukrajinskih vojnika u Hrvatskoj: 'To bi bilo dovođenje rata kod nas'". Telegram.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Jutarnji list - Doznajemo detalje: Ukrajinski vojnici bi na obuku dolazili u Hrvatsku, HV bi oformio i mobilne timove instruktora?". www.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "UŽIVO Milanović o ratu u Ukrajini: "Neki u EU parlamentu govore o 'kidanju Rusije' - to je mahnito. Mi i Srbi se nismo toliko mrzili"". Dnevnik.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 30 January 2023.

"Od 2014. do 2022. mi gledamo kako netko provocira Rusiju s namjerom da ovaj rat izbije. Izbio je. Prošlo je godinu dana, mi tek sada razgovaramo o tenkovima. Sve njemačke tenkove ćemo tamo poslati, ruski su izgorjeli. Ista sudbina očekuje i ove druge", dodao je Milanović.

- ^ Index.rs (17 March 2023). "Milanović: Vlada je poslala helikoptere Ukrajini, to vodi do masovnog krvoprolića". NOVA portal (in Serbian). Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ "Milanović: Ustaše su bili kavaliri za one koji su se borili uz pozdrav Slava Ukrajini". tportal.hr. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ "Milanović: Tko ne bude glasao protiv proširenja NATO-a, ja ću ga nazvati izdajnikom". www.index.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "Grlic-Radman: Croatia supports Nato membership for Finland and Sweden". www.n1info.hr. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Erdogan says Turkey opposed to Finland, Sweden NATO membership". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Turkey supports Finland and Sweden Nato bid". www.bbc.com/news. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Croatian President accuses Finland of "ignoring Croatia's interests"". N1 (in Croatian). 13 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Finska ministrica: Naši građani su malo zbunjeni zbog izjava Milanovića". Index.hr (in Croatian).

- ^ "'Za Milanovića je veliki udarac bio kad mu je Selak Raspudić rekla – gdje si sad, frajeru. On samome sebi radi problem i ovo je njegov politički poraz'". tportal.hr. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Israel has lost my sympathy, says Croatia's president". Politico. 13 October 2023.

- ^ Igra na sve ili ništa: Milanović je upravo učinio nešto što nikome prije njega nije palo na pamet

- ^ Milanović daje ostavku na mjesto predsjednika? Bit će kandidat za premijera, ide na parlamentarne izbore sa SDP-om!

- ^ Milanović ide na izbore sa SDP-om: Bit će kandidat za premijera

- ^ Milanović bacio ‘bombu‘ u eter, a evo za koga navija: Ja kad sam gorio za Hajduk, on je bio jak klub iz malog grada

- ^ STANKOVIĆ OSTAO U ČUDU: 'Milanović navijač Hajduka?! Nisam znao'

- ^ "Službeni predsjednika Republike Hrvatske, Zorana Milanovića Republici Čile" [The official visit President of the Republic of Croatia Zoran Milanović to the Republic of Chile] (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs. 15 December 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

Bibliography[edit]

Books[edit]

- Bajruši, Robert (2011). Zoran Milanović. Politička biografija (Biblioteka Političko pleme ed.). Zagreb: Naklada Jesenski i Turk. ISBN 978-953-222-423-8.

- Karlović Sabolić, Marina (2015). Zoran Milanović. Mladić koji je obećavao. Zagreb: Profil knjiga. ISBN 978-953-313-445-1.

Theses[edit]

- Prgomet, Edita (15 September 2016). Politička retorika Zorana Milanovića (bachelor thesis) (in Croatian). Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek. Department of Cultural studies. Chair in media culture.

- Gotovina, Ana (18 September 2018). Analiza televizijskog sučeljavanja Andreja Plenkovića i Zorana Milanovića (bachelor thesis) (in Croatian). VERN University of Applied Sciences.

- Vrdoljak, Ivana (26 July 2018). ANALIZA NEVERBALNE I PARAVERBALNE KOMUNIKACIJE ZORANA MILANOVIĆA (bachelor thesis) (in Croatian). Zagreb School of Business.

- Sibneraj, Ines (15 September 2020). Politički diskurs obraćanja Zorana Milanovića u Hrvatskom saboru (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science. Department of Journalism and Media Production.

- Topić, Patricija (17 September 2020). Strateško upravljanje karakterom u izbornim kampanjama - slučaj Zorana Milanovića (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science. Department of Strategic Communication.

- Ardalić, Lucija (13 July 2020). Retorika predsjedničke kampanje Zorana Milanovića na Facebooku 2019 (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science.

- Perošević, Lara (17 September 2020). Politička komunikacija kandidata na Facebooku na predsjedničkim izborima 2019./2020 (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science.

- Lokner, Gorana (28 November 2016). Medijski imidž Zorana Milanovića (bachelor thesis) (in Croatian). The Edward Bernays College of Communication Management. Department of Public Relations.

- Klimeš, Roberto (15 September 2020). Analiza i usporedba inauguracije Kolinde Grabar-Kitarović i Zorana Milanovića (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science.

- Baus, Valentina (25 September 2017). Politički stil kao alat političke komunikacije: usporedna analiza televizijskih nastupa Zorana Milanovića i Andreja Plenkovića u izbornoj kampanji 2016 (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science.

- Čosić, Marina (28 September 2016). Artikulacija ideoloških rascjepa u govorima Zorana Milanovića i Tomislava Karamarka: analiza diskursa 2012. - 2016 (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science. Department of Croatian Politics.

- Dragušica, Marija (23 September 2019). Usporedba političke retorike predsjednika SDP-a od 2000. do 2019. godine (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science. Department of Strategic Communication.

- Daničić, Marijana (21 September 2020). Populizam u komunikaciji predsjedničkih kandidata u izbornoj kampanji 2019. godine (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science.

- Kopčić, Ivana (14 September 2020). Predizborno sučeljavanje predsjedničkih kandidata na komercijalnim televizijama i javnom servisu na primjeru kampanje 2019. godine (master thesis) (in Croatian). University of Zagreb. The Faculty of Political Science.

- Car, Bruno (18 April 2018). Analiza neverbalne komunikacije kandidata za premijera tijekom političkog sučeljavanja na parlamentarnim izborima 2016 (bachelor thesis) (in Croatian). VERN University of Applied Sciences.

- Mamić, Hrvoje (21 November 2018). Argumentacija u postčinjeničnom razdoblju na primjeru odabranih političkih debata (master thesis) (in Croatian). VERN University of Applied Sciences.

Articles[edit]

- Denis Kuljiš. Prorok prije proroka: Briljantna priča o Zoranu Milanoviću. // START style & news, # 13, Spring 2020, pp. 71–73.

External links[edit]

- Bajruši, Robert (17 April 2007). "Zoran Milanovic – The Rise of Racan's Successor". Nacional. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- (in Croatian) Javno.com: Biography