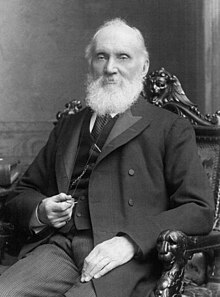

Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, OM, GCVO, PC, FRS, FRSE (26 June 1824 – 17 December 1907)[7] was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast.[8] He was the professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, where he undertook significant research and mathematical analysis of electricity, the formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and contributed significantly to unifying physics, which was then in its infancy of development as an emerging academic discipline. He received the Royal Society's Copley Medal in 1883 and served as its president from 1890 to 1895. In 1892, he became the first British scientist to be elevated to the House of Lords.[2]

Absolute temperatures are stated in units of kelvin in his honour. While the existence of a coldest possible temperature, absolute zero, was known before his work, Kelvin determined its correct value as approximately −273.15 degrees Celsius or −459.67 degrees Fahrenheit. The Joule–Thomson effect is also named in his honour.

He worked closely with mathematics professor Hugh Blackburn in his work. He also had a career as an electrical telegraph engineer and inventor which propelled him into the public eye and earned him wealth, fame, and honours. For his work on the transatlantic telegraph project, he was knighted in 1866 by Queen Victoria, becoming Sir William Thomson. He had extensive maritime interests and worked on the mariner's compass, which previously had limited reliability.

He was ennobled in 1892 in recognition of his achievements in thermodynamics, and of his opposition to Irish Home Rule,[9][10][11] becoming Baron Kelvin, of Largs in the County of Ayr. The title refers to the River Kelvin, which flows near his laboratory at the University of Glasgow's Gilmorehill home at Hillhead. Despite offers of elevated posts from several world-renowned universities, Kelvin refused to leave Glasgow, remaining until his retirement from that post in 1899.[7] Active in industrial research and development, he was recruited around 1899 by George Eastman to serve as vice-chairman of the board of the British company Kodak Limited, affiliated with Eastman Kodak.[12] In 1904 he became chancellor of the University of Glasgow.[7]

He resided in Netherhall, a redstone mansion in Largs, which he built in the 1870s and where he died in 1907. The Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow has a permanent exhibition on the work of Kelvin, which includes many of his original papers, instruments, and other artefacts, including his smoking pipe.

Early life and work[edit]

Family[edit]

Thomson's father, James Thomson, was a teacher of mathematics and engineering at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution and the son of a farmer. James Thomson married Margaret Gardner in 1817 and, of their children, four boys and two girls survived infancy. Margaret Thomson died in 1830 when William was six years old.[13]

William and his elder brother James were tutored at home by their father while the younger boys were tutored by their elder sisters. James was intended to benefit from the major share of his father's encouragement, affection and financial support and was prepared for a career in engineering.

In 1832, his father was appointed professor of mathematics at Glasgow, and the family moved there in October 1833. The Thomson children were introduced to a broader cosmopolitan experience than their father's rural upbringing, spending mid-1839 in London, and the boys were tutored in French in Paris. Much of Thomson's life during the mid-1840s was spent in Germany and the Netherlands. Language study was given a high priority.

His sister, Anna Thomson, was the mother of physicist James Thomson Bottomley FRSE.[14]

Youth[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Thomson had heart problems and nearly died when he was 9 years old. He attended the Royal Belfast Academical Institution, where his father was a professor in the university department. In 1834, aged 10, he began studying at the University of Glasgow, not out of any precociousness; the university provided many of the facilities of an elementary school for able pupils, and this was a typical starting age. In school, Thomson showed a keen interest in the classics along with his natural interest in the sciences. At age 12 he won a prize for translating Lucian of Samosata's Dialogues of the Gods from Ancient Greek to English.

In the academic year 1839/1840, Thomson won the class prize in astronomy for his "Essay on the figure of the Earth" which showed an early facility for mathematical analysis and creativity. His physics tutor at this time was his namesake, David Thomson.[15] Throughout his life, he would work on the problems raised in the essay as a coping strategy during times of personal stress. On the title page of this essay Thomson wrote the following lines from Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Man." These lines inspired Thomson to understand the natural world using the power and method of science:

Go, wondrous creature! mount where Science guides;

Go measure earth, weigh air, and state the tides;

Instruct the planets in what orbs to run,

Correct old Time, and regulate the sun;

Thomson became intrigued with Joseph Fourier's Théorie analytique de la chaleur (The Analytical Theory of Heat) and committed himself to study the "continental" mathematics resisted by a British establishment still working in the shadow of Sir Isaac Newton. Unsurprisingly, Fourier's work had been attacked by domestic mathematicians, Philip Kelland authoring a critical book. The book motivated Thomson to write his first published scientific paper[16] under the pseudonym P.Q.R., defending Fourier, which was submitted to The Cambridge Mathematical Journal by his father. A second P.Q.R. paper followed almost immediately.[17]

While on holiday with his family in Lamlash in 1841, he wrote a third, more substantial P.Q.R. paper On the uniform motion of heat in homogeneous solid bodies, and its connection with the mathematical theory of electricity.[18] In the paper he made remarkable connections between the mathematical theories of thermal conduction and electrostatics, an analogy that James Clerk Maxwell was ultimately to describe as one of the most valuable science-forming ideas.[19]

Cambridge[edit]

William's father was able to make a generous provision for his favourite son's education and, in 1841, installed him, with extensive letters of introduction and ample accommodation, at Peterhouse, Cambridge. While at Cambridge, Thomson was active in sports, athletics and sculling, winning the Colquhoun Sculls in 1843.[20] He took a lively interest in the classics, music, and literature; but the real love of his intellectual life was the pursuit of science. The study of mathematics, physics, and in particular, of electricity, had captivated his imagination. In 1845 Thomson graduated as second wrangler.[21] He also won the first Smith's Prize, which, unlike the tripos, is a test of original research. Robert Leslie Ellis, one of the examiners, is said to have declared to another examiner "You and I are just about fit to mend his pens."[22]

In 1845, he gave the first mathematical development of Michael Faraday's idea that electric induction takes place through an intervening medium, or "dielectric", and not by some incomprehensible "action at a distance". He also devised the mathematical technique of electrical images, which became a powerful agent in solving problems of electrostatics, the science which deals with the forces between electrically charged bodies at rest. It was partly in response to his encouragement that Faraday undertook the research in September 1845 that led to the discovery of the Faraday effect, which established that light and magnetic (and thus electric) phenomena were related.

He was elected a fellow of St. Peter's (as Peterhouse was often called at the time) in June 1845.[23] On gaining the fellowship, he spent some time in the laboratory of the celebrated Henri Victor Regnault, at Paris; but in 1846 he was appointed to the chair of natural philosophy in the University of Glasgow. At age 22 he found himself wearing the gown of a professor in one of the oldest universities in the country and lecturing to the class of which he was a first year student a few years before.

Thermodynamics[edit]

By 1847, Thomson had already gained a reputation as a precocious and maverick scientist when he attended the British Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Oxford. At that meeting, he heard James Prescott Joule making yet another of his, so far, ineffective attempts to discredit the caloric theory of heat and the theory of the heat engine built upon it by Sadi Carnot and Émile Clapeyron. Joule argued for the mutual convertibility of heat and mechanical work and for their mechanical equivalence.

Thomson was intrigued but sceptical. Though he felt that Joule's results demanded theoretical explanation, he retreated into an even deeper commitment to the Carnot–Clapeyron school. He predicted that the melting point of ice must fall with pressure, otherwise its expansion on freezing could be exploited in a perpetuum mobile. Experimental confirmation in his laboratory did much to bolster his beliefs.

In 1848, he extended the Carnot–Clapeyron theory further through his dissatisfaction that the gas thermometer provided only an operational definition of temperature. He proposed an absolute temperature scale[24] in which "a unit of heat descending from a body A at the temperature T° of this scale, to a body B at the temperature (T−1)°, would give out the same mechanical effect [work], whatever be the number T." Such a scale would be "quite independent of the physical properties of any specific substance."[25] By employing such a "waterfall", Thomson postulated that a point would be reached at which no further heat (caloric) could be transferred, the point of absolute zero about which Guillaume Amontons had speculated in 1702. "Reflections on the Motive Power of Heat", published by Carnot in French in 1824, the year of Lord Kelvin's birth, used −267 as an estimate of the absolute zero temperature. Thomson used data published by Regnault to calibrate his scale against established measurements.

In his publication, Thomson wrote:

... The conversion of heat (or caloric) into mechanical effect is probably impossible, certainly undiscovered

—But a footnote signalled his first doubts about the caloric theory, referring to Joule's very remarkable discoveries. Surprisingly, Thomson did not send Joule a copy of his paper, but when Joule eventually read it he wrote to Thomson on 6 October, claiming that his studies had demonstrated conversion of heat into work but that he was planning further experiments. Thomson replied on 27 October, revealing that he was planning his own experiments and hoping for a reconciliation of their two views.

Thomson returned to critique Carnot's original publication and read his analysis to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in January 1849,[26] still convinced that the theory was fundamentally sound. However, though Thomson conducted no new experiments, over the next two years he became increasingly dissatisfied with Carnot's theory and convinced of Joule's. In February 1851 he sat down to articulate his new thinking. He was uncertain of how to frame his theory, and the paper went through several drafts before he settled on an attempt to reconcile Carnot and Joule. During his rewriting, he seems to have considered ideas that would subsequently give rise to the second law of thermodynamics. In Carnot's theory, lost heat was absolutely lost, but Thomson contended that it was "lost to man irrecoverably; but not lost in the material world". Moreover, his theological beliefs led Thomson to extrapolate the second law to the cosmos, originating the idea of universal heat death.

I believe the tendency in the material world is for motion to become diffused, and that as a whole the reverse of concentration is gradually going on – I believe that no physical action can ever restore the heat emitted from the Sun, and that this source is not inexhaustible; also that the motions of the Earth and other planets are losing vis viva which is converted into heat; and that although some vis viva may be restored for instance to the earth by heat received from the sun, or by other means, that the loss cannot be precisely compensated and I think it probable that it is under-compensated.[27]

Compensation would require a creative act or an act possessing similar power,[27] resulting in a rejuvenating universe (as Thomson had previously compared universal heat death to a clock running slower and slower, although he was unsure whether it would eventually reach thermodynamic equilibrium and stop for ever).[28] Thomson also formulated the heat death paradox (Kelvin's paradox) in 1862, which uses the second law of thermodynamics to disprove the possibility of an infinitely old universe; this paradox was later extended by William Rankine.[29]

In final publication, Thomson retreated from a radical departure and declared "the whole theory of the motive power of heat is founded on ... two ... propositions, due respectively to Joule, and to Carnot and Clausius."[30] Thomson went on to state a form of the second law:

It is impossible, by means of inanimate material agency, to derive mechanical effect from any portion of matter by cooling it below the temperature of the coldest of the surrounding objects.[31]

In the paper, Thomson supports the theory that heat was a form of motion but admitts that he had been influenced only by the thought of Sir Humphry Davy and the experiments of Joule and Julius Robert von Mayer, maintaining that experimental demonstration of the conversion of heat into work was still outstanding.[32] As soon as Joule read the paper he wrote to Thomson with his comments and questions. Thus began a fruitful, though largely epistolary, collaboration between the two men, Joule conducting experiments, Thomson analysing the results and suggesting further experiments. The collaboration lasted from 1852 to 1856, its discoveries including the Joule–Thomson effect, sometimes called the Kelvin–Joule effect, and the published results[33] did much to bring about general acceptance of Joule's work and the kinetic theory.

Thomson published more than 650 scientific papers[2] and applied for 70 patents (not all were issued). Regarding science, Thomson wrote the following:

In physical science a first essential step in the direction of learning any subject is to find principles of numerical reckoning and practicable methods for measuring some quality connected with it. I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about and express it in numbers you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind: it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely, in your thoughts, advanced to the stage of science, whatever the matter may be.[34]

Transatlantic cable[edit]

Calculations on data rate[edit]

Though eminent in the academic field, Thomson was obscure to the general public. In September 1852, he married childhood sweetheart Margaret Crum, daughter of Walter Crum;[7] but her health broke down on their honeymoon, and over the next 17 years Thomson was distracted by her suffering. On 16 October 1854, George Gabriel Stokes wrote to Thomson to try to re-interest him in work by asking his opinion on some experiments of Faraday on the proposed transatlantic telegraph cable.

Faraday had demonstrated how the construction of a cable would limit the rate at which messages could be sent—in modern terms, the bandwidth. Thomson jumped at the problem and published his response that month.[35] He expressed his results in terms of the data rate that could be achieved and the economic consequences in terms of the potential revenue of the transatlantic undertaking. In a further 1855 analysis,[36] Thomson stressed the impact that the design of the cable would have on its profitability.

Thomson contended that the signalling speed through a given cable was inversely proportional to the square of the length of the cable. Thomson's results were disputed at a meeting of the British Association in 1856 by Wildman Whitehouse, the electrician of the Atlantic Telegraph Company. Whitehouse had possibly misinterpreted the results of his own experiments but was doubtless feeling financial pressure as plans for the cable were already well under way. He believed that Thomson's calculations implied that the cable must be "abandoned as being practically and commercially impossible".

Thomson attacked Whitehouse's contention in a letter to the popular Athenaeum magazine,[37] pitching himself into the public eye. Thomson recommended a larger conductor with a larger cross section of insulation. He thought Whitehouse no fool and suspected that he might have the practical skill to make the existing design work. Thomson's work had attracted the attention of the project's undertakers. In December 1856, he was elected to the board of directors of the Atlantic Telegraph Company.

Scientist to engineer[edit]

Thomson became scientific adviser to a team with Whitehouse as chief electrician and Sir Charles Tilston Bright as chief engineer, but Whitehouse had his way with the specification, supported by Faraday and Samuel F. B. Morse.

Thomson sailed on board the cable-laying ship HMS Agamemnon in August 1857, with Whitehouse confined to land owing to illness, but the voyage ended after 380 miles (610 km) when the cable parted. Thomson contributed to the effort by publishing in the Engineer the whole theory of the stresses involved in the laying of a submarine communications cable, showing when the line is running out of the ship, at a constant speed in a uniform depth of water, it sinks in a slant or straight incline from the point where it enters the water to that where it touches the bottom.[38]

Thomson developed a complete system for operating a submarine telegraph that was capable of sending a character every 3.5 seconds. He patented the key elements of his system, the mirror galvanometer and the siphon recorder, in 1858. Whitehouse still felt able to ignore Thomson's many suggestions and proposals. It was not until Thomson convinced the board that using purer copper for replacing the lost section of cable would improve data capacity, that he first made a difference to the execution of the project.[39]

The board insisted that Thomson join the 1858 cable-laying expedition, without any financial compensation, and take an active part in the project. In return, Thomson secured a trial for his mirror galvanometer, which the board had been unenthusiastic about, alongside Whitehouse's equipment. Thomson found the access he was given unsatisfactory, and the Agamemnon had to return home following a disastrous storm in June 1858. In London, the board was about to abandon the project and mitigate their losses by selling the cable. Thomson, Cyrus West Field and Curtis M. Lampson argued for another attempt and prevailed, Thomson insisting that the technical problems were tractable. Though employed in an advisory capacity, Thomson had, during the voyages, developed a real engineer's instincts and skill at practical problem-solving under pressure, often taking the lead in dealing with emergencies and being unafraid to assist in manual work. A cable was completed on 5 August.

Disaster and triumph[edit]

Thomson's fears were realised when Whitehouse's apparatus proved insufficiently sensitive and had to be replaced by Thomson's mirror galvanometer. Whitehouse continued to maintain that it was his equipment that was providing the service and started to engage in desperate measures to remedy some of the problems. He fatally damaged the cable by applying 2,000 volts. When the cable failed completely Whitehouse was dismissed, though Thomson objected and was reprimanded by the board for his interference. Thomson subsequently regretted that he had acquiesced too readily to many of Whitehouse's proposals and had not challenged him with sufficient vigour.[40]

A joint committee of inquiry was established by the Board of Trade and the Atlantic Telegraph Company. Most of the blame for the cable's failure was found to rest with Whitehouse.[41] The committee found that, though underwater cables were notorious in their lack of reliability, most of the problems arose from known and avoidable causes. Thomson was appointed one of a five-member committee to recommend a specification for a new cable. The committee reported in October 1863.[42]

In July 1865, Thomson sailed on the cable-laying expedition of the SS Great Eastern, but the voyage was dogged by technical problems. The cable was lost after 1,200 miles (1,900 km) had been laid, and the project was abandoned. A further attempt in 1866 laid a new cable in two weeks, and then recovered and completed the 1865 cable. The enterprise was feted as a triumph by the public, and Thomson enjoyed a large share of the adulation. Thomson, along with the other principals of the project, was knighted on 10 November 1866. To exploit his inventions for signalling on long submarine cables, Thomson entered into a partnership with C. F. Varley and Fleeming Jenkin. In conjunction with the latter, he also devised an automatic curb sender, a kind of telegraph key for sending messages on a cable.

Later expeditions[edit]

Thomson took part in the laying of the French Atlantic submarine communications cable of 1869, and with Jenkin was engineer of the Western and Brazilian and Platino-Brazilian cables, assisted by vacation student James Alfred Ewing. He was present at the laying of the Pará to Pernambuco section of the Brazilian coast cables in 1873.

Thomson's wife, Margaret, died on 17 June 1870, and he resolved to make changes in his life. Already addicted to seafaring, in September he purchased a 126-ton schooner, the Lalla Rookh[43][44] and used it as a base for entertaining friends and scientific colleagues. His maritime interests continued in 1871 when he was appointed to the Board of Enquiry into the sinking of HMS Captain.

In June 1873, Thomson and Jenkin were on board the Hooper, bound for Lisbon with 2,500 miles (4,020 km) of cable when the cable developed a fault. An unscheduled 16-day stop-over in Madeira followed, and Thomson became good friends with Charles R. Blandy and his three daughters. On 2 May 1874 he set sail for Madeira on the Lalla Rookh. As he approached the harbour, he signalled to the Blandy residence "Will you marry me?" and Fanny (Blandy's daughter Frances Anna Blandy) signalled back "Yes". Thomson married Fanny, 13 years his junior, on 24 June 1874.

Other contributions[edit]

Treatise on Natural Philosophy[edit]

Over the period 1855 to 1867, Thomson collaborated with Peter Guthrie Tait on a textbook that founded the study of mechanics first on the mathematics of kinematics, the description of motion without regard to force. The text developed dynamics in various areas but with constant attention to energy as a unifying principle. A second edition appeared in 1879, expanded to two separately bound parts. The textbook set a standard for early education in mathematical physics.

Atmospheric electricity[edit]

Thomson made significant contributions to atmospheric electricity for the relatively short time for which he worked on the subject, around 1859.[45] He developed several instruments for measuring the atmospheric electric field, using some of the electrometers he had initially developed for telegraph work, which he tested at Glasgow and whilst on holiday on Arran. His measurements on Arran were sufficiently rigorous and well-calibrated that they could be used to deduce air pollution from the Glasgow area, through its effects on the atmospheric electric field.[46] Thomson's water dropper electrometer was used for measuring the atmospheric electric field at Kew Observatory and Eskdalemuir Observatory for many years,[47] and one was still in use operationally at the Kakioka Observatory in Japan[48] until early 2021. Thomson may have unwittingly observed atmospheric electrical effects caused by the Carrington event (a significant geomagnetic storm) in early September 1859.[45]

Vortex theory of the atom[edit]

Between 1870 and 1890 the vortex atom theory, which purported that an atom was a vortex in the aether, was popular among British physicists and mathematicians. Thomson pioneered the theory, which was distinct from the 17th century vortex theory of René Descartes in that Thomson was thinking in terms of a unitary continuum theory, whereas Descartes was thinking in terms of three different types of matter, each relating respectively to emission, transmission, and reflection of light.[49] About 60 scientific papers were written by approximately 25 scientists. Following the lead of Thomson and Tait,[50] the branch of topology called knot theory was developed. Thompson's initiative in this complex study that continues to inspire new mathematics has led to persistence of the topic in history of science.[51]

Marine[edit]

Thomson was an enthusiastic yachtsman, his interest in all things relating to the sea perhaps arising from, or fostered by, his experiences on the Agamemnon and the Great Eastern. Thomson introduced a method of deep-sea depth sounding, in which a steel piano wire replaces the ordinary hand line. The wire glides so easily to the bottom that "flying soundings" can be taken while the ship is at full speed. A pressure gauge to register the depth of the sinker was added by Thomson. About the same time he revived the Sumner method of finding a ship's position, and calculated a set of tables for its ready application.

During the 1880s, Thomson worked to perfect the adjustable compass to correct errors arising from magnetic deviation owing to the increased use of iron in naval architecture. Thomson's design was a great improvement on the older instruments, being steadier and less hampered by friction. The deviation caused by the ship's magnetism was corrected by movable iron masses at the binnacle. Thomson's innovations involved much detailed work to develop principles identified by George Biddell Airy and others, but contributed little in terms of novel physical thinking. Thomson's energetic lobbying and networking proved effective in gaining acceptance of his instrument by The Admiralty.

Scientific biographers of Thomson, if they have paid any attention at all to his compass innovations, have generally taken the matter to be a sorry saga of dim-witted naval administrators resisting marvellous innovations from a superlative scientific mind. Writers sympathetic to the Navy, on the other hand, portray Thomson as a man of undoubted talent and enthusiasm, with some genuine knowledge of the sea, who managed to parlay a handful of modest ideas in compass design into a commercial monopoly for his own manufacturing concern, using his reputation as a bludgeon in the law courts to beat down even small claims of originality from others, and persuading the Admiralty and the law to overlook both the deficiencies of his own design and the virtues of his competitors'.

The truth, inevitably, seems to lie somewhere between the two extremes.[52]

Charles Babbage had been among the first to suggest that a lighthouse might be made to signal a distinctive number by occultations of its light, but Thomson pointed out the merits of the Morse code for the purpose, and urged that the signals should consist of short and long flashes of the light to represent the dots and dashes.

Electrical standards[edit]

Thomson did more than any other electrician up to his time in introducing accurate methods and apparati for measuring electricity. As early as 1845 he pointed out that the experimental results of William Snow Harris were in accordance with the laws of Coulomb. In the Memoirs of the Roman Academy of Sciences for 1857 he published a description of his divided ring electrometer, based on the electroscope of Johann Gottlieb Friedrich von Bohnenberger. He introduced a chain or series of effective instruments, including the quadrant electrometer, which cover the entire field of electrostatic measurement. He invented the current balance, also known as the Kelvin balance or Ampere balance (SiC), for the precise specification of the ampere, the standard unit of electric current. From around 1880 he was aided by the electrical engineer Magnus Maclean FRSE in his electrical experiments.[53]

In 1893, Thomson headed an international commission to decide on the design of the Niagara Falls power station. Despite his belief in the superiority of direct current electric power transmission, he endorsed Westinghouse's alternating current system which had been demonstrated at the Chicago World's Fair of that year. Even after Niagara Falls, Thomson still held to his belief that direct current was the superior system.[54]

Acknowledging his contribution to electrical standardisation, the International Electrotechnical Commission elected Thomson as its first president at its preliminary meeting, held in London on 26–27 June 1906. "On the proposal of the President [Mr Alexander Siemens, Great Britain], secounded [sic] by Mr Mailloux [US Institute of Electrical Engineers] the Right Honorable Lord Kelvin, G.C.V.O., O.M., was unanimously elected first President of the Commission", minutes of the Preliminary Meeting Report read.[55]

Age of Earth[edit]

Kelvin made an early physics-based estimation of the age of Earth. Given his youthful work on the figure of Earth and his interest in heat conduction, it is no surprise that he chose to investigate Earth's cooling and to make historical inferences of Earth's age from his calculations. Thomson was a creationist in a broad sense, but he was not a 'flood geologist'[56] (a view that had lost mainstream scientific support by the 1840s.[57][58] He contended that the laws of thermodynamics operated from the birth of the universe and envisaged a dynamic process that saw the organisation and evolution of the Solar System and other structures, followed by a gradual "heat death". He developed the view that Earth had once been too hot to support life and contrasted this view with that of uniformitarianism, that conditions had remained constant since the indefinite past. He contended that "This earth, certainly a moderate number of millions of years ago, was a red-hot globe … ."[59]

After the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859, Thomson saw evidence of the relatively short habitable age of Earth as tending to contradict Darwin's gradualist explanation of slow natural selection bringing about biological diversity. Thomson's own views favoured a version of theistic evolution sped up by divine guidance.[60] His calculations showed that the Sun could not have possibly existed long enough to allow the slow incremental development by evolution—unless it was heated by an energy source beyond the knowledge of Victorian era science. He was soon drawn into public disagreement with geologists and with Darwin's supporters John Tyndall and T. H. Huxley. In his response to Huxley's address to the Geological Society of London (1868) he presented his address "Of Geological Dynamics" (1869)[61] which, among his other writings, challenged the geologists' assertion that Earth must be vastly old, perhaps billions of years in age.[62]

Thomson's initial 1864 estimate of Earth's age was from 20 to 400 million years old. These wide limits were due to his uncertainty about the melting temperature of rock, to which he equated Earth's interior temperature,[63][64] as well as the uncertainty in thermal conductivities and specific heats of rocks. Over the years he refined his arguments and reduced the upper bound by a factor of ten, and in 1897 Thomson, now Lord Kelvin, ultimately settled on an estimate that Earth was 20–40 million years old.[59][65] In a letter published in Scientific American Supplement 1895 Kelvin criticized geologists' estimates of the age of rocks and the age of Earth, including the views published by Darwin, as "vaguely vast age".[66]

His exploration of this estimate can be found in his 1897 address to the Victoria Institute, given at the request of the institute's president George Stokes,[67] as recorded in that institute's journal Transactions.[68] Although his former assistant John Perry published a paper in 1895 challenging Kelvin's assumption of low thermal conductivity inside Earth, and thus showing a much greater age,[69] this had little immediate impact. The discovery in 1903 that radioactive decay releases heat led to Kelvin's estimate being challenged, and Ernest Rutherford famously made the argument in a 1904 lecture attended by Kelvin that this provided the unknown energy source Kelvin had suggested, but the estimate was not overturned until the development in 1907 of radiometric dating of rocks.[62]

The discovery of radioactivity largely invalidated Kelvin's estimate of the age of Earth. Although he eventually paid off a gentleman's bet with Strutt on the importance of radioactivity in Earth's geology, he never publicly acknowledged this because he thought he had a much stronger argument restricting the age of the Sun to no more than 20 million years. Without sunlight, there could be no explanation for the sediment record on Earth's surface. At the time, the only known source for solar energy was gravitational collapse. It was only when thermonuclear fusion was recognised in the 1930s that Kelvin's age paradox was truly resolved.[70] However, modern cosmology recognizes the Kelvin period in the early life of a star, during which it shines from gravitational energy (correctly calculated by Kelvin) before fusion and the main sequence begins.

Later life and death[edit]

In the winter of 1860–61 Kelvin slipped on the ice while curling near his home at Netherhall and fractured his leg, causing him to miss the 1861 Manchester meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and to limp thereafter.[7] He remained something of a celebrity on both sides of the Atlantic until his death.

Thomson remained a devout believer in Christianity throughout his life; attendance at chapel was part of his daily routine.[71] He saw his Christian faith as supporting and informing his scientific work, as is evident from his address to the annual meeting of the Christian Evidence Society[72] on 23 May 1889.[73]

In the 1902 Coronation Honours list published on 26 June 1902 (the original day of the coronation of Edward VII and Alexandra),[74] Kelvin was appointed a Privy Councillor and one of the first members of the new Order of Merit (OM). He received the order from the King on 8 August 1902[75][76] and was sworn a member of the council at Buckingham Palace on 11 August 1902.[77] In his later years he often travelled to his town house at 15 Eaton Place, off Eaton Square in London's Belgravia.[7]

In November 1907 he caught a chill and his condition deteriorated until he died at his Scottish country seat, Netherhall, in Largs on 17 December.[78] At the request of Westminster Abbey, the undertakers Wylie & Lochhead prepared an oak coffin lined with lead. In the dark of the winter evening the cortege set off from Netherhall for Largs railway station, a distance of about a mile. Large crowds witnessed the passing of the cortege, and shopkeepers closed their premises and dimmed their lights. The coffin was placed in a special Midland and Glasgow and South Western Railway van. The train set off at 8:30 pm for Kilmarnock, where the van was attached to the overnight express to St Pancras railway station in London.[79]

Kelvin's funeral was on 23 December 1907.[7] The Abbey was crowded, including representatives from the University of Glasgow and the University of Cambridge, along with representatives from France, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, and Monaco. Kelvin's grave is in the nave, near the choir screen, and close to the graves of Isaac Newton, John Herschel, and Charles Darwin.[80] Darwin's son, Sir George Darwin, was one of the pall-bearers.[81]

The University of Glasgow held a memorial service for Kelvin in the Bute Hall. Kelvin had been a member of the Scottish Episcopal Church, attached to St Columba's Episcopal Church in Largs, and when in Glasgow to St Mary's Episcopal Church (now, St Mary's Cathedral, Glasgow).[79] At the same time as the funeral in Westminster Abbey, a service was held in St Columba's Episcopal Church, Largs, attended by a large congregation including burgh dignitaries.[82]

Lord Kelvin is memorialised on the Thomson family grave in Glasgow Necropolis. The family grave has a second modern memorial, erected by the Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow; a society of which he was president in the periods 1856–58 and 1874–77.[83]

Legacy[edit]

Limits of classical physics[edit]

In 1884, Lord Kelvin led a master class on "Molecular Dynamics and the Wave Theory of Light" at Johns Hopkins University.[84] Kelvin referred to the acoustic wave equation describing sound as waves of pressure in air and attempted to describe also an electromagnetic wave equation, presuming a luminiferous aether susceptible to vibration. The study group included Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley who subsequently performed the Michelson–Morley experiment, which found no luminiferous aether. Kelvin did not provide a text, but A. S. Hathaway took notes and duplicated them with a papyrograph. As the subject matter was under active development, Kelvin amended that text and in 1904 it was typeset and published. Kelvin's attempts to provide mechanical models ultimately failed in the electromagnetic regime. Starting from his lecture in 1884, he was the first scientist to formulate the hypothetical concept of dark matter; he then attempted to define and locate some "dark bodies" in the Milky Way.[85][86]

He was skeptical about Maxwell's prediction of radiation pressure, but admitted that it did exist after seeing Lebedew's experimental proof of radiation pressure.[87]

On 27 April 1900 he gave a widely reported lecture titled "Nineteenth-Century Clouds over the Dynamical Theory of Heat and Light" to the Royal Institution.[88][89] The two "dark clouds" he was alluding to were confusion surrounding how matter moves through the aether (including the puzzling results of the Michelson–Morley experiment) and indications that the equipartition theorem in statistical mechanics might break down. Two major physical theories were developed during the 20th century starting from these issues: for the former, the theory of relativity; for the second, quantum mechanics. In 1905 Albert Einstein published the so-called annus mirabilis papers, one of which explained the photoelectric effect based on Max Planck's discovery of energy quanta which was the foundation of quantum mechanics, another of which described special relativity, and the last of which explained Brownian motion in terms of statistical mechanics, providing a strong argument for the existence of atoms.

Pronouncements later proven to be false[edit]

Like many scientists, Thomson made some mistakes in predicting the future of technology.

His biographer Silvanus P. Thompson writes that "When Röntgen's discovery of the X-rays was announced at the end of 1895, Lord Kelvin was entirely skeptical, and regarded the announcement as a hoax. The papers had been full of the wonders of Röntgen's rays, about which Lord Kelvin was intensely skeptical until Röntgen himself sent him a copy of his Memoir"; on 17 January 1896, having read the paper and seen the photographs, he wrote Röntgen a letter saying that "I need not tell you that when I read the paper I was very much astonished and delighted. I can say no more now than to congratulate you warmly on the great discovery you have made"[90] Kelvin had his own hand X-rayed in May 1896.[91]

His forecast for practical aviation (i.e., heavier-than-air aircraft) was negative. In 1896 he refused an invitation to join the Aeronautical Society, writing "I have not the smallest molecule of faith in aerial navigation other than ballooning or of expectation of good results from any of the trials we hear of."[92] In a 1902 newspaper interview he predicted that "No balloon and no aeroplane will ever be practically successful."[93]

A statement falsely attributed to Kelvin is: "There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement." This has been widely misattributed to Kelvin since the 1980s, either without citation or stating that it was made in an address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1900).[94] There is no evidence that Kelvin said this,[95][96] and the quote is instead a paraphrase of Albert A. Michelson, who in 1894 stated: "… it seems probable that most of the grand underlying principles have been firmly established … An eminent physicist remarked that the future truths of physical science are to be looked for in the sixth place of decimals."[96] Similar statements were given earlier by others, such as Philipp von Jolly.[97] The attribution to Kelvin in 1900 is presumably a confusion with his "Two clouds" lecture and which on the contrary pointed out areas that would subsequently see revolutions.

In 1898, Kelvin predicted that only 400 years of oxygen supply remained on the planet, due to the rate of burning combustibles.[98][99] In his calculation, Kelvin assumed that photosynthesis was the only source of free oxygen; he did not know all of the components of the oxygen cycle.[dubious ] He could not even have known all of the sources of photosynthesis: for example the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus—which accounts for more than half of marine photosynthesis—was not discovered until 1986.

Eponyms[edit]

A variety of physical phenomena and concepts with which Thomson is associated are named Kelvin, including:

- Kelvin bridge (also known as Thomson bridge)

- Kelvin functions

- Kelvin–Helmholtz instability

- Kelvin–Helmholtz luminosity

- Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism

- Kelvin material

- Joule–Kelvin effect

- Kelvin sensing

- Kelvin transform in potential theory

- Kelvin wake pattern

- Kelvin water dropper

- Kelvin wave

- Kelvin's heat death paradox

- Kelvin's circulation theorem

- Kelvin–Stokes theorem

- Kelvin–Varley divider

- The SI unit of temperature, kelvin

Mount Kelvin in New Zealand's Paparoa Range was named after him by botanist William Trownson.[100]

Honours[edit]

- Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1847.

- Keith Medal, 1864.

- Gunning Victoria Jubilee Prize, 1887.

- President, 1873–1878, 1886–1890, 1895–1907.

- Foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1851.

- Fellow of the Royal Society, 1851.

- Royal Medal, 1856.

- Copley Medal, 1883.

- President, 1890–1895.

- Hon. Member of the Royal College of Preceptors (College of Teachers), 1858.

- Hon. Member of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland, 1859.[101]

- Knighted 1866.[102]

- Commander of the Imperial Order of the Rose (Brazil), 1873.

- Commander of the Legion of Honour (France), 1881.

- Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour, 1889.

- Knight of the Prussian Order Pour le Mérite, 1884.

- Commander of the Order of Leopold (Belgium), 1890.

- Baron Kelvin, of Largs in the County of Ayr, 1892.[103] The title derives from the River Kelvin, which runs by the grounds of the University of Glasgow. His title died with him, as he was survived by neither heirs nor close relations.

The memorial of William Thomson, Baron Kelvin in Kelvingrove Park next to the University of Glasgow - Knight Grand Cross of the Victorian Order, 1896.[104]

- Honorary degree Legum doctor (LL.D.), Yale University, 5 May 1902.[105]

- One of the first members of the Order of Merit, 1902.[106]

- Privy Counsellor, 11 August 1902.[77]

- Honorary degree Doctor mathematicae from the Royal Frederick University on 6 September 1902, when they celebrated the centenary of the birth of mathematician Niels Henrik Abel.[107][108]

- First international recipient of John Fritz Medal, 1905.

- Order of the First Class of the Sacred Treasure of Japan, 1901.

- He is buried in Westminster Abbey, London next to Isaac Newton.

- Lord Kelvin was commemorated on the £20 note issued by the Clydesdale Bank in 1971; in the current issue of banknotes, his image appears on the bank's £100 note. He is shown holding his adjustable compass and in the background is a map of the transatlantic cable.[109]

- In 2011 he was inducted to the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame.[110]

- World Refrigeration Day, is 26 June. It was chosen to celebrate his birth date and has been held annually, since 2019.

Arms[edit]

|

|

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Grabiner, Judy (2002). "Creators of Mathematics: The Irish Connection (book review)" (PDF). Irish Math. Soc. Bull. 48: 67. doi:10.33232/BIMS.0048.65.68. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Sharlin, Harold I. (2019). "William Thomson, Baron Kelvin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Significant Scots. William Thomson (Lord Kelvin)". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "William Thomson, Lord Kelvin. Scientist, Mathematician and Engineer". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

His first wife was Margaret Crum and he married secondly Frances Blandy but had no children.

- ^ Ranford, Paul (September 2019). John William Strutt-- the 3rd Baron Rayleigh (1842–1919): Recently studied correspondence. p. 25.

- ^ Thomson, William (1849). "An Account of Carnot's Theory of the Motive Power of Heat; with Numerical Results deduced from Regnault's Experiments on Steam". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 16 (5): 541–574. doi:10.1017/s0080456800022481. S2CID 120335729.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Crosbie. "Thomson, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36507. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Martin, Elizabeth, ed. (2009), "Kelvin, Sir William Thomson, Lord", The New Oxford Dictionary for Scientific Writers and Editors (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545155.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-954515-5,

British theoretical and experimental physicist

- Knowles, Elizabeth, ed. (2014), Lord Kelvin Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (8th ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199668700.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-966870-0,

Lord Kelvin 1824–1907 British physicist and natural philosopher

- Clapham, Christopher; Nicholson, James, eds. (2014), "Kelvin, Lord", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Mathematics (5th ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199679591.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967959-1,

Kelvin, Lord (1824–1907) The British mathematician, physicist and engineer

- Schaschke, Carl, ed. (2014), "Kelvin, Lord", A Dictionary of Chemical Engineering, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199651450.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-965145-0,

A Belfast-born Scottish scientist

- Ridpath, Ian, ed. (2018), "Kelvin, Lord", A Dictionary of Astronomy (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780191851193.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-185119-3,

Kelvin, Lord (William Thomson) (1824–1907) Scottish physicist

- Ratcliffe, Susan, ed. (2018). Lord Kelvin Oxford Essential Quotations (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780191866692.001.0001.

Lord Kelvin 1824–1907 British scientist

- Rennie, Richard; Law, Jonathan, eds. (2019), "Kelvin, Lord", A Dictionary of Physics (8th ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198821472.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-882147-2,

Kelvin, Lord (William Thomson; 1824–1907) British physicist

- Law, Jonathan; Rennie, Richard, eds. (2020), "Kelvin, Lord", A Dictionary of Chemistry (8th ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198841227.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-884122-7,

Kelvin, Lord (William Thomson; 1824–1907) British physicist, born in Belfast

- Martin, Elizabeth, ed. (2009), "Kelvin, Sir William Thomson, Lord", The New Oxford Dictionary for Scientific Writers and Editors (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545155.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-954515-5,

- ^ Flood, Raymond; McCartney, Mark; Whitaker, Andrew (28 April 2009). "Kelvin and Ireland". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 158: 011001. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/158/1/011001. S2CID 250690809.

- ^ Randall, Lisa (2005). Warped Passages. New York: HarperCollins. p. 162. ISBN 0-06-053109-6.

- ^ Hutchison, Iain (2009). "Lord Kelvin and Liberal Unionism". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 158 (1). IOP Publishing: 012004. Bibcode:2009JPhCS.158a2004H. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/158/1/012004. S2CID 250693895.

- ^ Trainer, Matthew (2008). "Lord Kelvin, Recipient of The John Fritz Medal in 1905". Physics in Perspective. 10: 212–223. doi:10.1007/s00016-007-0344-4. S2CID 124435108.

- ^ "Biography of William Thomson's father". Groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ "Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1783–2002" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ "David Thomson 17 Nov 1817 – 31st Jan 1880". Aberdeen University.

- ^ P.Q.R. (1841). "On Fourier's expansions of functions in trigonometric series". Cambridge Mathematical Journal. 2: 258–262.

- ^ P.Q.R. (1841). "Note on a passage in Fourier's 'Heat'". Cambridge Mathematical Journal. 3: 25–27.

- ^ P.Q.R. (1842). "On the uniform motion of heat and its connection with the mathematical theory of electricity". Cambridge Mathematical Journal. 3: 71–84. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511996009.004.

- ^ Niven, W.D., ed. (1965). The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell, 2 vols. Vol. 2. New York: Dover. p. 301.

- ^ Mayer, Roland (1978). Peterhouse Boat Club 1828–1978. Peterhouse Boat Club. p. 5. ISBN 0-9506181-0-1.

- ^ "Thomson, William (THN841W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus (1910). The Life of William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs. Vol. 1. MacMillan and Co., Limited. p. 98.

- ^ McCartney, Mark (1 December 2002). "William Thomson: king of Victorian physics". Physics World. Archived from the original on 15 July 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ Chang, H. (2004). "4". Inventing Temperature: Measurement and Scientific Progress. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517127-3.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1848). "On an Absolute Thermometric Scale founded on Carnot's Theory of the Motive Power of Heat, and calculated from Regnault's observations". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 100–106. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996009.040. ISBN 978-1-108-02898-1.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1849). "An Account of Carnot's Theory of the Motive Power of Heat; with Numerical Results deduced from Regnault's Experiments on Steam". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–164. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996009.042. ISBN 978-1-108-02898-1.

- ^ a b Sharlin, p. 112.

- ^ Otis, Laura (2002). "Literature and Science in the Nineteenth Century: An Anthology". OUP Oxford. Vol. 1. pp. 60–67.

- ^ Thomson, William (1862). "On the Age of the Sun's Heat". Macmillan's Magazine. Vol. 5. pp. 388–393.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1852). "On the dynamical theory of heat; with numerical results deduced from Mr. Joule's equivalent of a thermal unit and M. Regnault's observations on steam". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 174–332. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996009.049. ISBN 978-1-108-02898-1.

- ^ Thomson, W. (March 1851). "On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with numerical results deduced from Mr Joule's equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M. Regnault's Observations on Steam". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. XX (part II): 261–268, 289–298. Also published in Thomson, W. (December 1852). "On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with numerical results deduced from Mr Joule's equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M. Regnault's Observations on Steam". Phil. Mag. 4. IV (22): 8–21.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1851) p.183

- ^ Joule, J. P.; Thomson, W. (30 June 2011). "On the thermal effects of fluids in motion". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 333–455. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996009.050.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1891). Popular Lectures and Addresses, Vol. I. London: MacMillan. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-598-77599-3. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1855). "On the theory of the electric telegraph". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–76. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996016.009. ISBN 978-1-108-02899-8.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1855). "On Peristaltic Induction of Electric Currents". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–91 [87]. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996016.011.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1856). "Letters on "telegraphs to America"". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–102. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996016.012. ISBN 978-1-108-02899-8.

- ^ Thomson, W. (1865). "On the forces concerned in the laying and lifting of deep-sea cables". Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–167. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511996016.020. ISBN 978-1-108-02899-8.

- ^ Sharlin, p. 141.

- ^ Sharlin, p. 144.

- ^ "Board of Trade Committee to Inquire into … Submarine Telegraph Cables', Parl. papers (1860), 52.591, no. 2744

- ^ "Report of the Scientific Committee Appointed to Consider the Best Form of Cable for Submersion Between Europe and America" (1863)

- ^ Gurney, Alan (2005). "Chapter 19: Thomson's Compass and Binnacle". Compass: A Story of Exploration and Innovation. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-60883-0.

- ^ "Lord Kelvin's sailing yacht 'Lalla Rookh', c 1860–1900". stock images.

- ^ a b Aplin, K. L.; Harrison, R. G. (3 September 2013). "Lord Kelvin's atmospheric electricity measurements". History of Geo- and Space Sciences. 4 (2): 83–95. arXiv:1305.5347. Bibcode:2013HGSS....4...83A. doi:10.5194/hgss-4-83-2013. S2CID 9783512.

- ^ Aplin, Karen L. (April 2012). "Smoke emissions from industrial western Scotland in 1859 inferred from Lord Kelvin's atmospheric electricity measurements". Atmospheric Environment. 50: 373–376. Bibcode:2012AtmEn..50..373A. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.12.053.

- ^ Harrison, R. G. (2003). "Twentieth-century atmospheric electrical measurements at the observatories of Kew, Eskdalemuir and Lerwick". Weather. 58 (1): 11–19. Bibcode:2003Wthr...58...11H. doi:10.1256/wea.239.01. S2CID 122673748.

- ^ Takeda, M.; Yamauchi, M.; Makino, M.; Owada, T. (2011). "Initial effect of the Fukushima accident on atmospheric electricity". Geophysical Research Letters. 38 (15). Bibcode:2011GeoRL..3815811T. doi:10.1029/2011GL048511. S2CID 73530372.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (2002). "The Vortex Atom: A Victorian Theory of Everything". Centaurus. 44 (1–2): 32–114. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0498.2002.440102.x. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Thomson, Wm. (1867). "On Vortex Atoms". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 6: 94–105. doi:10.1017/S0370164600045430.

- ^ Silliman, Robert H. (1963). "William Thomson: Smoke Rings and Nineteenth-Century Atomism". Isis. 54 (4): 461–474. doi:10.1086/349764. JSTOR 228151. S2CID 144988108.

- ^ Lindley, p. 259

- ^ "Maclean, Magnus, 1857–1937, electrical engineer". University of Strathclyde Archives. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Lindley, p. 293

- ^ IEC. "1906 Preliminary Meeting Report, pp 46–48" (PDF). The minutes from our first meeting. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ Sharlin, p. 169.

- ^ Imbrie, John; Imbrie, Katherine Palmer (1986). Ice ages: solving the mystery. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-674-44075-3.

- ^ Young, Davis A.; Stearley, Ralph F. (2008). The Bible, rocks, and time : geological evidence for the age of the earth. Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Academic. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8308-2876-0.

- ^ a b Burchfield, Joe D. (1990). Lord Kelvin and the Age of the Earth. University of Chicago Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-226-08043-7.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (1983). The eclipse of Darwinism: anti-Darwinian evolution theories in the decades around 1900 (paperback ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-8018-4391-4.

- ^ ""Of Geological Dynamics" excerpts". Zapatopi.net. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ a b Kelvin did pay off gentleman's bet with Strutt on the importance of radioactivity in the Earth. The Kelvin period does exist in the evolution of stars. They shine from gravitational energy for a while (correctly calculated by Kelvin) before fusion and the main sequence begins. Fusion was not understood until well after Kelvin's time. England, P.; Molnar, P.; Righter, F. (January 2007). "John Perry's neglected critique of Kelvin's age for the Earth: A missed opportunity in geodynamics". GSA Today. 17 (1): 4–9. Bibcode:2007GSAT...17R...4E. doi:10.1130/GSAT01701A.1.

- ^ Tung, K. K. (2007) Topics in Mathematical Modeling. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691116426. pp. 243–251. In Thomson's theory the Earth's age is proportional to the square of the difference between interior temperature and surface temperature, so that the uncertainty in the former leads to an even larger relative uncertainty in the age.

- ^ Thomson, William (1862). "On the Secular Cooling of the Earth". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. XXIII: 160–161. doi:10.1017/s0080456800018512. S2CID 126038615.

- ^ Hamblin, W. Kenneth (1989). The Earth's Dynamic Systems 5th ed. Macmillan Publishing Company. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-02-349381-2.

- ^ Heuel-Fabianek, Burkhard. "Natürliche Radioisotope: die "Atomuhr" für die Bestimmung des absoluten Alters von Gesteinen und archäologischen Funden". StrahlenschutzPraxis. 1/2017: 31–42.

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus Phillips (January 1977). "The life of Lord Kelvin". American Journal of Physics. 45 (10): 1095. Bibcode:1977AmJPh..45.1010T. doi:10.1119/1.10735. ISBN 978-0-8284-0292-7.

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus Phillips (January 1977). "The life of Lord Kelvin". American Journal of Physics. 45 (10): 998. Bibcode:1977AmJPh..45.1010T. doi:10.1119/1.10735. ISBN 978-0-8284-0292-7.

- ^ Perry, John (1895) "On the age of the earth," Nature, 51 : 224–227, 341–342, 582–585. (51:224, 51:341, 51:582 at Internet Archive)

- ^ Stacey, Frank D. (2000). "Kelvin's age of the Earth paradox revisited". Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (B6): 13155–13158. Bibcode:2000JGR...10513155S. doi:10.1029/2000JB900028.

- ^ McCartney & Whitaker (2002), reproduced on Institute of Physics website

- ^ Thomson, W. (1889) Address to the Christian Evidence Society

- ^ The Finality of this Globe, Hampshire Telegraph, 15 June 1889, p. 11.

- ^ "The Coronation Honours". The Times. No. 36804. London. 26 June 1902. p. 5.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36842. London. 9 August 1902. p. 6.

- ^ "No. 27470". The London Gazette. 2 September 1902. p. 5679.

- ^ a b "No. 27464". The London Gazette. 12 August 1902. p. 5173.

- ^ "Death of Lord Kelvin". Times

- ^ a b The Scotsman, 23 December 1907

- ^ Hall, Alfred Rupert (1966) The Abbey Scientists. London: Roger & Robert Nicholson. p. 62.

- ^ Glasgow Herald, 24 December 1907

- ^ Glasgow Evening Times, 23 December 1907

- ^ Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow (2008). No Mean Society: 200 years of the Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow. 2nd Ed (PDF). Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-9544965-0-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Kargon, Robert and Achinstein, Peter (1987) Kelvin's Baltimore Lectures and Modern Theoretical Physics: historical and philosophical perspectives. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-11117-9

- ^ "How dark matter became a particle". CERN Courier. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "A History of Dark Matter- Gianfranco Bertone & Dan Hooper". ned.ipac.caltech.edu.

- ^ Khramov, Yu A (31 December 1986). "Petr Nikolaevich Lebedev and his school (On the 120th anniversary of the year of his birth)". Soviet Physics Uspekhi. 29 (12): 1127–1134. doi:10.1070/PU1986v029n12ABEH003609. ISSN 0038-5670.

- ^ "Lord Kelvin, Nineteenth Century Clouds over the Dynamical Theory of Heat and Light", reproduced in Notices of the Proceedings at the Meetings of the Members of the Royal Institution of Great Britain with Abstracts of the Discourses, Volume 16, p. 363–397

- ^ The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Series 6, volume 2, pages 1–40 (1901)

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus (1910). The Life of William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs. Vol. 2. MacMillan and Co., Limited.

- ^ The Royal Society, London

- ^ Letter from Lord Kelvin to Baden Powell 8 December 1896

- ^ Interview in the Newark Advocate 26 April 1902

- ^ Davies, Paul and Brown, Julian. (1988) Superstring: A theory of everything?. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780521437752

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2007) Einstein: His Life and Universe. Simon & Schuster. p. 575. ISBN 9781416586913

- ^ a b Horgan, John (1996) The End of Science. Broadway Books. p. 19. ISBN 9780553061741

- ^ Lightman, Alan P. (2005). The discoveries: great breakthroughs in twentieth-century science, including the original papers. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf Canada. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-676-97789-9.

- ^ "Papers Past—Evening Post—30 July 1898—A Startling Scientific Prediction". Paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "The Evening News – Google News Archive Search". Archived from the original on 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Place name detail: Mount Kelvin". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "Honorary Members and Fellows". Institution of Engineers in Scotland. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "No. 23185". The London Gazette. 16 November 1866. p. 6062.

- ^ "No. 26260". The London Gazette. 23 February 1892. p. 991.

- ^ "No. 26758". The London Gazette. 14 July 1896. p. 4026.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36760. London. 6 May 1902. p. 5.

- ^ "No. 27470". The London Gazette. 2 September 1902. p. 5679.

- ^ "Foreign degrees for British men of Science". The Times. No. 36867. London. 8 September 1902. p. 4.

- ^ "Honorary doctorates from the University of Oslo 1902–1910". (in Norwegian)

- ^ "Current Banknotes : Clydesdale Bank". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ "Lord Kelvin biography – Science Hall of Fame – National Library of Scotland". digital.nls.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus (1910). The Life of William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs. Vol. 2. MacMillan and Co., Limited. p. 914.

Cited sources[edit]

- Lindley, D. (2004). Degrees Kelvin: A Tale of Genius, Invention and Tragedy. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-309-09073-5.

- Sharlin, H. I. (1979). Lord Kelvin: The Dynamic Victorian. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00203-3.

Kelvin's works[edit]

- Thomson, W.; Tait, P. G. (1867). Treatise on Natural Philosophy. Oxford. 2nd edition, 1883. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-108-00537-1)

- ——; Tait, P. G (1872). Elements of Natural Philosophy. At the University press. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01448-9) 2nd edition, 1879.

- Elasticity and heat. Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black. 1880.

- Thomson, W. (1881). Shakespeare and Bacon on Vivisection. Sands & McDougall.

- ——; Tait, P. G (1872). Elements of Natural Philosophy. At the University press. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01448-9) 2nd edition, 1879.

- —— (1882–1911). Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge University Press. (6 volumes)

- Volume I. 1841–1853 (Internet Archive)

- Volume II. 1853–1856 (Internet Archive)

- Volume III. Elasticity, heat, electro-magnetism (Internet Archive)

- Volume IV. Hydrodynamics and general dynamics (Hathitrust)

- Volume V. Thermodynamics, cosmical and geological physics, molecular and crystalline theory, electrodynamics (Internet Archive)

- Volume VI. Voltaic theory, radioactivity, electrions, navigation and tides, miscellaneous (Internet Archive)

- —— (1904). Baltimore Lectures on Molecular Dynamics and the Wave Theory of Light. Bibcode:2010blmd.book.....T. LCCN 04015391. OCLC 1041059646. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-00767-2)

- —— (1912). "Collected Papers in Physics and Engineering". Nature. 90 (2256): 563–565. ASIN B0000EFOL8. Bibcode:1913Natur..90..563P. doi:10.1038/090563a0. S2CID 3957852.

- Wilson, D. B., ed. (1990). The Correspondence Between Sir George Gabriel Stokes and Sir William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs. (2 vols), Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32831-9.

- Hörz, H. (2000). Naturphilosophie als Heuristik?: Korrespondenz zwischen Hermann von Helmholtz und Lord Kelvin (William Thomson). Basilisken-Presse. ISBN 978-3-925347-56-6.

Biography, history of ideas and criticism[edit]

- Buchwald, J. Z. (1977). "William Thomson and the mathematization of Faraday's electrostatics". Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. 8: 101–136. doi:10.2307/27757369. JSTOR 27757369.

- Cardoso Dias, D.M. (1996). "William Thomson and the Heritage of Caloric". Annals of Science. 53 (5): 511–520. doi:10.1080/00033799600200361.

- Gooding, D. (1980). "Faraday, Thomson, and the concept of the magnetic field". British Journal for the History of Science. 13 (2): 91–120. doi:10.1017/S0007087400017726. S2CID 145573114.

- Gossick, B. R. (1976). "Heaviside and Kelvin: a study in contrasts". Annals of Science. 33 (3): 275–287. doi:10.1080/00033797600200561.

- Gray, A. (1908). Lord Kelvin: An Account of His Scientific Life and Work. London: J. M. Dent & Co.

- Green, G. & Lloyd, J. T. (1970). "Kelvin's instruments and the Kelvin Museum". American Journal of Physics. 40 (3): 496. Bibcode:1972AmJPh..40..496G. doi:10.1119/1.1986598. ISBN 978-0-85261-016-9.

- Hearn, Chester G. (2004). Circuits in the Sea: the men, the ships, and the Atlantic cable. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

- Kargon, Robert; Achinstein, Peter; Brown, Laurie M. (1987). Kargon, R. H.; Achinstein, P. (eds.). "Kelvin's Baltimore Lectures and Modern Theoretical Physics; Historical and Philosophical Perspectives". Physics Today. 42 (1): 82–84. Bibcode:1989PhT....42a..82K. doi:10.1063/1.2810888. ISBN 978-0-262-11117-1.

- King, A. G. (1925). "Kelvin the Man". Nature. 117 (2933): 79. Bibcode:1926Natur.117R..79.. doi:10.1038/117079b0. S2CID 4094894.

- King, E. T. (1909). "Lord Kelvin's Early Home". Nature. 82 (2099): 331–333. Bibcode:1910Natur..82..331J. doi:10.1038/082331a0. S2CID 3974629.

- Knudsen, O. (1972). "From Lord Kelvin's notebook: aether speculations". Centaurus. 16 (1): 41–53. Bibcode:1972Cent...16...41K. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1972.tb00164.x.

- Lekner, J. (2012). "Nurturing genius: the childhood and youth of Kelvin and Maxwell" (PDF). New Zealand Science Review.

- McCartney, M.; Whitaker, A., eds. (2002). Physicists of Ireland: Passion and Precision. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7503-0866-3.

- May, W. E. (1979). "Lord Kelvin and his compass". Journal of Navigation. 32: 122–134. doi:10.1017/S037346330003318X. S2CID 122538244.

- Munro, J. (1891). Heroes of the Telegraph. London: Religious Tract Society.

- Murray, D. (1924). Lord Kelvin as Professor in the Old College of Glasgow. Glasgow: Maclehose & Jackson.

- Russell, A. (1912). Lord Kelvin: His Life and Work. London: T. C. & E. C.Jack. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Smith, C. & Wise, M. N. (1989). Energy and Empire: A Biographical Study of Lord Kelvin. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26173-9. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Thompson, S. P. (1910). Life of William Thomson: Baron Kelvin of Largs. London: Macmillan. In two volumes Volume 1 Volume 2

- Tunbridge, P. (1992). Lord Kelvin: His Influence on Electrical Measurements and Units. Peter Peregrinus: London. ISBN 978-0-86341-237-0.

- Wilson, D. (1910). William Thomson, Lord Kelvin: His Way of Teaching. Glasgow: John Smith & Son.

- Wilson, D. B. (1987). Kelvin and Stokes: A Comparative Study in Victorian Physics. Bristol: Hilger. ISBN 978-0-85274-526-7.

External links[edit]

- Works by Lord Kelvin at Project Gutenberg

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Lord Kelvin", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Works by or about Lord Kelvin at Internet Archive

- Works by Lord Kelvin at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Heroes of the Telegraph at The Online Books Page

- "Horses on Mars", from Lord Kelvin

- William Thomson: king of Victorian physics at Institute of Physics website

- Measuring the Absolute: William Thomson and Temperature Archived 2 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Hasok Chang and Sang Wook Yi (PDF file)

- Reprint of papers on electrostatics and magnetism (gallica)

- The molecular tactics of a crystal (Internet Archive)

- Quotations. This collection includes sources for many quotes.

- Kelvin Building Opening – The Leys School, Cambridge (1893)

- The Kelvin Library

- William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

- 19th-century British physicists

- 1824 births

- 1907 deaths

- 19th-century British mathematicians

- 20th-century British mathematicians

- Academics of the University of Glasgow

- Alumni of Peterhouse, Cambridge

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- British physicists

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- Catastrophism

- Chancellors of the University of Glasgow

- Elders of the Church of Scotland

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fluid dynamicists

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- John Fritz Medal recipients

- Knights Bachelor

- Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Ordained peers

- People associated with electricity

- People educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution

- People of the Industrial Revolution

- Irish physicists

- Presidents of the Physical Society

- Presidents of the Royal Society

- Presidents of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Royal Medal winners

- Second Wranglers

- Scientists from Belfast

- Theistic evolutionists

- Creators of temperature scales

- Ulster Scots people

- Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees

- Recipients of the Matteucci Medal

- Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society

- Peers of the United Kingdom created by Queen Victoria