White horses in mythology

White horses have a special significance in the mythologies of cultures around the world. They are often associated with the sun chariot,[1] with warrior-heroes, with fertility (in both mare and stallion manifestations), or with an end-of-time saviour, but other interpretations exist as well. Both truly white horses and the more common grey horses, with completely white hair coats, were identified as "white" by various religious and cultural traditions.

Portrayal in myth[edit]

From earliest times, white horses have been mythologised as possessing exceptional properties, transcending the normal world by having wings (e.g. Pegasus from Greek mythology), or having horns (the unicorn). As part of its legendary dimension, the white horse in myth may be depicted with seven heads (Uchaishravas) or eight feet (Sleipnir), sometimes in groups or singly. There are also white horses which are divinatory, who prophesy or warn of danger.

As a rare or distinguished symbol, a white horse typically bears the hero- or god-figure in ceremonial roles or in triumph over negative forces. Herodotus reported that white horses were held as sacred animals in the Achaemenid court of Xerxes the Great (ruled 486–465 BC),[2] while in other traditions the reverse happens when it was sacrificed to the gods.

In more than one tradition, the white horse carries patron saints or the world saviour in the end times (as in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), is associated with the sun or sun chariot (Ossetia) or bursts into existence in a fantastic way, emerging from the sea or a lightning bolt.

Though some mythologies are stories from earliest beliefs, other tales, though visionary or metaphorical, are found in liturgical sources as part of preserved, on-going traditions (see, for example, "Iranian tradition" below).

Mythologies and traditions[edit]

European[edit]

Celtic[edit]

In Welsh mythology, Rhiannon, a mythic figure in the Mabinogion collection of legends, rides a "pale-white" horse.[3] Because of this, she has been linked to the Romano-Celtic fertility horse goddess Epona and other instances of the veneration of horses in early Indo-European culture.[4] In Irish Myth Donn "god of the dead" portrayed as a phantom horseman riding a white horse, is considered an aspect of The Dagda "the great God" also known as "the horseman" and is the origin of the Irish "Loch nEachach" for Loch Neagh. In Irish myth horses are said to be symbols of sovereignty and the sovereignty goddess Macha is associated with them. One of Cúchulainn's chariot-horses was called Liath Macha or "Macha's Grey"[citation needed]

The La Tène style hill figure in England, the Uffington White Horse dates back to the Bronze Age and is similar to some Celtic coin horse designs.

In Scottish folklore, the kelpie or each uisge, a deadly supernatural water demon in the shape of a horse, is sometimes described as white, though other stories say it is black.

Greek[edit]

In Greek mythology, the white winged horse Pegasus was the son of Poseidon and the gorgon Medusa. Poseidon was also the creator of horses, creating them out of the breaking waves when challenged to make a beautiful land animal.

A secondary pair of twins fathered by Zeus, Amphion and Zethus, the legendary founders of Thebes, are called "Dioskouroi, riders of white horses" (λευκόπωλος) by Euripides in his play The Phoenician Women (the same epithet is used in Heracles and in the lost play Antiope).[5][6][7]

Norse[edit]

In Norse mythology, Odin's eight-legged horse Sleipnir, "the best horse among gods and men", is described as grey.[8] Sleipnir is also the ancestor of another grey horse, Grani, who is owned by the hero Sigurd.[9]

Slavic[edit]

In Slavic mythology, the war and fertility deity Svantovit owned an oracular white horse; the historian Saxo Grammaticus, in descriptions similar to those of Tacitus centuries before, says the priests divined the future by leading the white stallion between a series of fences and watching which leg, right or left, stepped first in each row.[10]

Hungarian[edit]

One of the titles of God in Hungarian mythology was Hadúr, who, according to an unconfirmed source, wears pure copper and is a metalsmith. The Hungarian name for God was, and remains "Isten" and they followed Steppe Tengriism.[citation needed] The ancient Magyars sacrificed white stallions to him before a battle.[11] Additionally, there is a story (mentioned for example in Gesta Hungarorum) that the Magyars paid a white horse to Moravian chieftain Svatopluk I (in other forms of the story, it is instead the Bulgarian chieftain Salan) for a part of the land that later became the Kingdom of Hungary.[citation needed] Actual historical background of the story is dubious because Svatopluk I was already dead when the first Hungarian tribes arrived. On the other hand, even Herodotus mentions in his Histories an Eastern custom, where sending a white horse as payment in exchange for land means casus belli. This custom roots in the ancient Eastern belief that stolen land would lose its fertility.[citation needed]

Iranian[edit]

In Zoroastrianism, one of the three representations of Tishtrya, the hypostasis of the star Sirius, is that of a white stallion (the other two are as a young man, and as a bull). The divinity takes this form during the last 10 days of every month of the Zoroastrian calendar, and also in a cosmogonical battle for control of rain. In this latter tale (Yasht 8.21–29), which appears in the Avesta's hymns dedicated to Tishtrya, the divinity is opposed by Apaosha, the demon of drought, which appears as a black stallion.[12]

White horses are also said to draw divine chariots, such as that of Aredvi Sura Anahita, who is the Avesta's divinity of the waters. Representing various forms of water, her four horses are named "wind", "rain", "clouds" and "sleet" (Yasht 5.120).

Indic[edit]

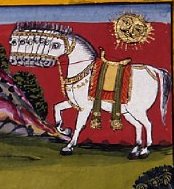

White horses appear many times in Hindu mythology and stand for the sun.[13] The Vedic horse sacrifice or ashvamedha was a fertility and kingship ritual involving the sacrifice of a sacred grey or white stallion.[14]

In the Puranas, one of the precious objects that emerged during the legend of the churning of the ocean by the devas and the asuras was Uchchaihshravas, a snow-white horse with seven heads.[14] Turaga was another divine white horse that emerged from the ocean and taken by the sun god Surya.[15][16] Uchchaihshravas was at times ridden by Indra, the king of the devas. Indra is depicted as having a liking for white horses in several legends – he often steals the sacrificial horse to the consternation of all involved, such as in the story of Sagara,[17] or the story of King Prithu.[18]

The chariot of the solar deity Surya is drawn by seven horses, alternately described as all white, or as the colours of the rainbow.

Hayagriva, an avatar of Vishnu, is worshipped as a god of knowledge and wisdom. His iconography depicts him with a human body and a horse's head, brilliant white in colour, with white garments, and seated on a white lotus. Kalki, the tenth incarnation of Vishnu and final world saviour, is predicted to appear riding a white horse, or in the form of a white horse.[14]

Buddhist[edit]

Kanthaka was a white horse that was a royal servant and favourite horse of Prince Siddhartha, who later became Gautama Buddha. Siddhartha used Kanthaka in all major events described in Buddhist texts prior to his renunciation of the world. Following the departure of Siddhartha, it was said that Kanthaka died of a broken heart.[19]

Abrahamic[edit]

Jewish[edit]

The Book of Zechariah twice mentions coloured horses; in the first passage there are three colours (red, dappled, and white), and in the second there are four teams of horses (red, black, white, and finally dappled) pulling chariots. The second set of horses are referred to as "the four spirits of heaven, going out from standing in the presence of the Lord of the whole world." They are described as patrolling the earth and keeping it peaceful.

Christian[edit]

In the New Testament, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse include one seated on a white horse[20] and one on a pale horse – the "white" horse carried the rider Conquest (traditionally, Pestilence) while the "pale" horse carried the rider Death.[21] However, the Greek word chloros, translated as pale, is often interpreted as sickly green or ashen grey rather than white. Later in the Book of Revelation, Christ rides a white horse out of heaven at the head of the armies of heaven to judge and make war upon the earth.[22]

Two Christian saints are associated with white steeds: Saint James, as patron saint of Spain, rides a white horse in his martial aspect.[23][24][25] Saint George, the patron saint of horsemen[26] among other things, also rides a white horse.[27] In Ossetia, the deity Uastyrdzhi, who embodied both the warrior and sun motifs often associated with white horses, became identified with the figure of St. George after the region adopted Christianity.[28]

Gesta Francorum contains a description of the First Crusade, where soldiers fighting at Antioch claimed to have been heartened by a vision of St. George and white horses during the battle: There came out from the mountains, also, countless armies with white horses, whose standards were all white. And so, when our leaders saw this army, they ... recognised the aid of Christ, whose leaders were St. George, Mercurius, and Demetrius.[29]

Islamic[edit]

Islamic culture tells of a white creature named Al-Buraq who brought Muhammad to Jerusalem during the Night Journey. Al-Buraq was also said to transport Abraham (Ibrâhîm) when he visited his wife Hagar (Hājar) and son Ishmael (Ismâ'îl). According to tradition, Abraham lived with one wife (Sarah) in Syria, but Al-Buraq would transport him in the morning to Makkah to see his family there, and then take him back to his Syrian wife in the evening. Al-Burāq (Arabic: البُراق al-Burāq "lightning") isn't mentioned in the Quran but in some hadith ("tradition") literature.[30]

Twelver Shī'a Islamic traditions envisage that the Mahdi will appear riding a white horse.[31]

Far East[edit]

Korean[edit]

A huge white horse appears in Korean mythology in the story of the kingdom of Silla. When the people gathered to pray for a king, the horse emerged from a bolt of lightning, bowing to a shining egg. After the horse flew back to heaven, the egg opened and the boy Park Hyeokgeose emerged. When he grew up, he united six warring states.

Philippines[edit]

The city of Pangantucan has as its symbol a white stallion who saved an ancient tribe from massacre by uprooting a bamboo and thus warning them of the enemy's approach.

Vietnamese[edit]

The city of Hanoi honours a white horse as its patron saint with a temple dedicated to this revered spirit, the White Horse or Bach Ma Temple ( "bach" means white and "ma" is horse). The 11th-century king, Lý Công Uẩn (also known as King Lý Thái Tổ) had a vision of a white horse representing a river spirit which showed him where to build his citadel.[32]

Native American[edit]

In Blackfoot mythology, the snow deity Aisoyimstan is a white-coloured man in white clothing who rides a white horse.

Literature and art[edit]

The mythological symbolism of white horses has been picked up as a trope in literature, film, and other storytelling. For example, the heroic prince or white knight of fairy tales often rides a white horse. Unicorns are (generally white) horse-like creatures with a single horn. And the English nursery rhyme "Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross" refers to a lady on a white horse who may be associated with the Celtic goddess Rhiannon.[33]

A "white palfrey" appears in the fairy tale "Virgilius the Sorcerer" by Andrew Lang. It appears in The Violet Fairy Book and attributes more than usual magical powers to the ancient Roman poet Virgil (see also Virgil#Mysticism and hidden meanings).

Gandalf, a protagonist and wizard in The Lord of the Rings rides on his white mount Shadowfax, who is described as being silver in color. Later in the series, Gandalf becomes known as White Rider.[34]

The British author G. K. Chesterton wrote an epic poem titled Ballad of the White Horse. In Book I, "The Vision of the King," he writes of earliest England, invoking the white horse hill figure and the gods:

Before the gods that made the gods

Had seen their sunrise pass,

The White Horse of the White Horse Vale

Was cut out of the grass.[35]

The Rip, a 2008 song by Portishead also invokes the imagery of white horses

Wild, white horses

They will take me away

And the tenderness I feel

Will send the dark underneath

Will I follow?[36]

The white horse is a recurring motif in Ibsen's play Rosmersholm, making use of the common Norse folklore that its appearance was a portent of death. The basis for the superstition may have been that the horse was a form of Church Grim, buried alive at the original consecration of the church building (the doomed protagonist in the play was a pastor), or that it was a materialisation of the fylgje, an individual's or family's guardian spirit.[37]

See also[edit]

- Horse in Chinese mythology

- Horse symbolism

- Horses in Germanic paganism

- Horse sacrifice

- Horse worship

- List of fictional horses

- Sun mythology

- White (horse)

- White horse (disambiguation)

- White horse of Kent

- White Horse Prophecy

- White Horse Stone

- Legendary horses in the Jura

- Legendary horses of Pas-de-Calais

References[edit]

- ^ The Complete Dictionary of Symbols by Jack Tresidder, Chronicle Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8118-4767-4, page 241. Google books copy

- ^ "White Horses and Genetics". Archaeology.about.com. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ The Four Branches of the Mabinogi: The Mabinogi of Pwyll by Will Parker (Bardic Press: 2007) ISBN 978-0-9745667-5-7. online text. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ Hyland, Ann (2003) The Horse in the Ancient World. Stroud, Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2160-9. Page 6.

- ^ Sanko, Siarhei (2018). "Reflexes of Ancient Ideas about Divine Twins in the Images of Saints George and Nicholas in Belarusian Folklore". Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore. 72: 15–40. doi:10.7592/fejf2018.72.sanko. ISSN 1406-0957.

- ^ Roman, Luke; Roman, Monica (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology. Infobase Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4381-2639-5.

- ^ "Apollodorus, Library, book 3, chapter 5, section 5". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda, page 36. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- ^ Morris, William (Trans.) and Magnússon, Eiríkr (Trans.) (2008). The Story of the Volsungs, page 54. Forgotten Books. ISBN 1-60506-469-6

- ^ The Trinity-Тројство-Триглав @ veneti.info, quoting Saxo Grammaticus in the "Gesta Danorum".

- ^ Peeps at Many Lands – Hungary by H. T. Kover, READ BOOKS, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4067-4416-3, page 8. Google books copy

- ^ Brunner, Christopher J. (1987). "Apōš". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 161–162.

- ^ Kak, Subhash (2002). The Aśvamedha: The Rite and Its Logic. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120818774.

- ^ a b c Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend by Anna L. Dallapiccola. Thames and Hudson, 2002. ISBN 0-500-51088-1.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. ISBN 9780143414216.

- ^ bigelow, mason. Isles of Wonder: the cover story. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781326407360.

- ^ The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa: Book 3, Vana Parva. Translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, 1883–1896.Section CVII. online edition at Sacred Texts. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ Śrīmad Bhāgavatam Canto 4, Chapter 19: King Pṛthu's One Hundred Horse Sacrifices translated by The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc.

- ^ Malasekera, G. P. (1996). Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. Government of Sri Lanka.

- ^ New Testament: Book of Revelation, Ch 6:2 (NIV)

- ^ New Testament: Book of Revelation, Ch 6:8 (NIV)

- ^ New Testament: Book of Revelation, Ch 19:11-6 (NIV)

- ^ "Dictionary of Phrase and Fable by E. Cobham Brewer, 1898". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ The Pilgrimage to Compostela in the Middle Ages by Maryjane Dunn and Linda Kay Davidson. Routledge, 2000. Page 115. ISBN 978-0-415-92895-3. Google books copy. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ The Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820 by Joseph J. Rishel and Suzanne L. Stratton. Yale University Press, 2006. page 318. ISBN 978-0-300-12003-5. Google books copy. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ Patron Saints Index: Saint George. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ The Meaning of Icons by Vladimir Lossky. St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0-913836-99-6. page 137. Google books copy. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ The Religion of Ossetia: Uastyrdzhi and Nart Batraz in Ossetian mythology. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ Gesta Francorum:The Defeat of Kerbogha, excerpt online at Medieval Sourcebook. Retrieved November 2008.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:58:227

- ^

Gilkes, F. Carl Gilkes; Gilkes, R. Carl Gilkes (2009). Introduction to the Endtimes. Xulon Press. p. 51. ISBN 9781615791057. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

The Muslims expect their own savior, the twelfth Iman, the Muhammad d'ul Mahdi, to come to the earth before Jesus returns. Their Mahdi will solve all their problems ... they believe that their twelfth Iman will come riding a white horse.

- ^ "1995 article with images by Barbara Cohen". Thingsasian.com. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "A Possible Solution to the Banbury Cross Mystery". Kton.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "Character Bios: Shadowfax". Henneth-Annun Story Archive. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ "Chesterton, G.K.Ballad of the White Horse (1929) (need additional citation material)". Infomotions.com. 31 December 2001. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "Genius.com - Portishead the rip lyrics". Genius. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ Holtan, Orley (1970). Mythic Patterns in Ibsen's Last Plays. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 55–6. ISBN 978-0-8166-0582-8.