Wells Fargo

Company logo since 2019 | |

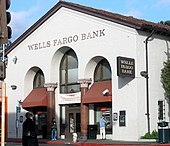

Wells Fargo's office in San Francisco, California | |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| |

| ISIN | US9497461015 |

| Industry | |

| Predecessors | |

| Founded | January 24, 1929 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. (as Northwest Bancorporation) April 1983 (as Norwest Corporation) November 2, 1998 (as Wells Fargo & Company) |

| Founders | (Wells Fargo Bank) |

| Headquarters | Sioux Falls, South Dakota, U.S. (legal);[1] 30 Hudson Yards[2] New York, NY 10001 U.S. (executive)[3][4] |

Number of locations | |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 238,698 (2022) |

| Subsidiaries | |

| Website | wellsfargo.com |

| Footnotes / references [5] | |

Wells Fargo & Company is an American multinational financial services company with a significant global presence.[8][5] The company operates in 35 countries and serves over 70 million customers worldwide.[5] It is a systemically important financial institution according to the Financial Stability Board, and is considered one of the "Big Four Banks" in the United States, alongside JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Citigroup.[9]

The firm's primary subsidiary is Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., a national bank that designates its Sioux Falls, South Dakota, site as its main office (and therefore is treated by most U.S. federal courts as a citizen of South Dakota).[1] It is the fourth-largest bank in the United States by total assets and is also one of the largest as ranked by bank deposits and market capitalization. It has 8,050 branches and 13,000 automated teller machines[5] and 2,000 stand-alone mortgage branches. It is the second-largest retail mortgage originator in the United States, originating one out of every four home loans[10] and services $1.8 trillion in home mortgages, one of the largest servicing portfolios in the US.[5] It is one of the most valuable bank brands.[11][12] Wells Fargo is ranked 47th on the Fortune 500 list of the largest companies in the U.S.[13]

In addition to banking, the company provides equipment financing via subsidiaries including Wells Fargo Rail and provides investment management and stockbrokerage services. A key part of Wells Fargo's business strategy is cross-selling, the practice of encouraging existing customers to buy additional banking services.[14][15][16][17] This led to the Wells Fargo cross-selling scandal.

Wells Fargo has international offices in London, Dublin, Paris, Dubai, Singapore, Tokyo, Shanghai, Beijing, and Toronto, among others.[18] Back-offices are in India and the Philippines with more than 20,000 staff.[19]

Wells Fargo operates under Charter No. 1, the first national bank charter issued in the United States. This charter was issued to First National Bank of Philadelphia on June 20, 1863, by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.[20] Wells Fargo, in its present form, is a result of a merger between the original Wells Fargo & Company and Minneapolis-based Norwest Corporation in 1998. The merged company took the better-known Wells Fargo name and moved to Wells Fargo's hub in San Francisco. At the same time, Norwest's banking subsidiary merged with Wells Fargo's Sioux Falls-based banking subsidiary. Wells Fargo became a coast-to-coast bank with the 2008 acquisition of Charlotte-based Wachovia.

History[edit]

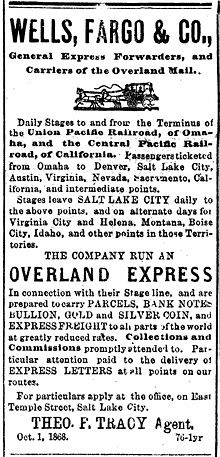

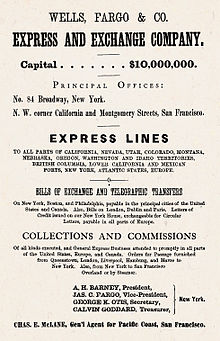

Henry Wells and William G. Fargo, who founded American Express along with John Butterfield, formed Wells Fargo & Company in 1852 to provide "express" and banking services to California, which was growing rapidly due to the California Gold Rush.[21] Its earliest and most significant tasks included transporting gold from the Philadelphia Mint and "express" mail delivery that was faster and less expensive than U.S. Mail. American Express was not interested in serving California.

By the end of the California Gold Rush, Wells Fargo was a dominant express and banking organization in the West, making large shipments of gold and delivering mail and supplies. It was also the primary lender of Butterfield Overland Mail Company, which ran a 2,757-mile route through the Southwest to San Francisco and was nicknamed the "Butterfield Line" after the name of the company's president, John Butterfield. In 1860, Congress failed to pass the annual Post Office appropriation bill, leaving the Post Office unable to pay Overland Mail Company. This caused Overland to default on its debts to Wells Fargo, allowing Wells Fargo to take control of the mail route.[22] Wells Fargo then operated the western portion of the Pony Express.[23]

Six years later, the "Grand Consolidation" united Wells Fargo, Holladay, and Overland Mail stage lines under the Wells Fargo name.[24]

In 1872, Lloyd Tevis, a friend of the Central Pacific "Big Four" and holder of rights to operate an express service over the Transcontinental Railroad, became president of the company after acquiring a large stake, a position he held until 1892.[25]

In 1905, Wells Fargo separated its banking and express operations, and Wells Fargo's bank merged with the Nevada National Bank to form the Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank.[26]

During the First World War, the United States government nationalized Wells Fargo's express business into a federal agency known as the US Railway Express Agency (REA).[27] After the war, the REA was privatized and continued service until 1975.

In 1923, Wells Fargo Nevada merged with the Union Trust Company to form the Wells Fargo Bank & Union Trust Company.[28]

In 1954, Wells Fargo & Union Trust shortened its name to Wells Fargo Bank. Four years later, it merged with American Trust Company to form the Wells Fargo Bank American Trust Company.[29] It changed its name back to Wells Fargo Bank in 1962.

In 1968, Wells Fargo was converted to a federal banking charter and became Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. In that same year, Wells Fargo merged with Henry Trione's Sonoma Mortgage in a $10.8 million stock transfer, making Trione the largest shareholder in Wells Fargo until Warren Buffett and Walter Annenberg surpassed him.[30]

One year later, Wells Fargo & Company holding company was formed, with Wells Fargo Bank as its main subsidiary.[31]

In September 1983, a Wells Fargo armored truck depot in West Hartford, Connecticut, was the victim of the White Eagle robbery.[32] The robbery was organized by Los Macheteros (a guerrilla group seeking Puerto Rican independence from the United States) and involved an insider armored truck guard. It was the largest US bank theft to date with $7.1 million stolen.[33][34]

Throughout the 1980s and '90s, Wells Fargo completed a series of acquisitions. In 1986, it acquired Crocker National Bank from Midland Bank.[35][36] Then, in 1987 it acquired the personal trust business of Bank of America.[37] In 1988, it acquired Barclays Bank of California from Barclays plc.[38] In 1991, Wells Fargo spent $491 million to acquire 130 branches in California from Great American Bank.[39] In 1996, Wells Fargo acquired First Interstate Bancorp for $11.6 billion.[40] Integration went poorly as many executives left.[41][42]

Wells Fargo became the first major US financial services firm to offer internet banking, in May 1995.[43]

After its string of acquisitions, in 1998, Wells Fargo Bank was acquired by Norwest Corporation of Minneapolis, with the combined company assuming the Wells Fargo name.[44][45]

It then began on another set of acquisitions, starting in 2000, when Wells Fargo Bank acquired National Bank of Alaska and First Security Corporation.[46] In late 2001, it acquired H.D. Vest Financial Services for $128 million, but sold it in 2015 for $580 million.[47] In 2007, Wells Fargo acquired Greater Bay Bancorp, which had $7.4 billion in assets, in a $1.5 billion transaction.[48][49][50][51] It also acquired Placer Sierra Bank and CIT Group's construction unit that same year.[52][53][54] In 2008, Wells Fargo acquired United Bancorporation of Wyoming and Century Bancshares of Texas.[55][56]

On October 3, 2008, after Wachovia turned down an inferior offer from Citigroup, Wachovia agreed to be bought by Wells Fargo for about $14.8 billion in stock.[57] The next day, a New York state judge issued a temporary injunction blocking the transaction from going forward while the competing offer from Citigroup was sorted out.[58] Citigroup alleged that it had an exclusivity agreement with Wachovia that barred Wachovia from negotiating with other potential buyers. The injunction was overturned late in the evening on October 5, 2008, by the New York state appeals court.[59] Citigroup and Wells Fargo then entered into negotiations brokered by the FDIC to reach an amicable solution to the impasse. The negotiations failed. Citigroup was unwilling to take on more risk than the $42 billion that would have been the cap under the previous FDIC-backed deal (with the FDIC incurring all losses over $42 billion). Citigroup did not block the merger, but sought damages of $60 billion for breach of an alleged exclusivity agreement with Wachovia.[60]

On October 28, 2008, Wells Fargo received $25 billion of funds via the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act in the form of a preferred stock purchase by the United States Department of the Treasury.[61][62] As a result of requirements of the government stress tests, the company raised $8.6 billion in capital in May 2009.[63] On December 23, 2009, Wells Fargo redeemed $25 billion of preferred stock issued to the United States Department of the Treasury. As part of the redemption of the preferred stock, Wells Fargo also paid accrued dividends of $131.9 million, bringing the total dividends paid to $1.441 billion since the preferred stock was issued in October 2008.[64]

In April 2009, Wells Fargo acquired North Coast Surety Insurance Services.[65]

In 2010, hedge fund administrator Citco purchased the trust company operation of Wells Fargo in the Cayman Islands.[66]

In 2011, the company hired 25 investment bankers from Citadel LLC.[67][68][69]

In April 2012, Wells Fargo acquired Merlin Securities.[70][71] In December 2012, it was rebranded as Wells Fargo Prime Services.[72] In December of that year, Wells Fargo acquired a 35% stake in The Rock Creek Group LP. The stake was increased to 65% in 2014 but sold back to management in July 2018.[73]

In 2015, Wells Fargo Rail acquired GE Capital Rail Services and merged in with First Union Rail.[74] In late 2015, Wells Fargo acquired three GE units focused on business loans equipment financing.[75]

In March 2017, Wells Fargo announced a plan to offer smartphone-based transactions with mobile wallets including Wells Fargo Wallet, Android Pay and Samsung Pay.[76]

In June 2018, Wells Fargo sold all 52 of its physical bank branch locations in Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio to Flagstar Bank.[77][78][79]

In September 2018, Wells Fargo announced it would cut 26,450 jobs by 2020 to reduce costs by $4 billion.[80][81]

In March 2019, CEO Tim Sloan resigned amidst the Wells Fargo account fraud scandal and former general counsel C. Allen Parker became interim CEO.[82]

In July 2019, Principal Financial Group acquired the company's Institutional Retirement & Trust business.[83]

On September 27, 2019, Charles Scharf was announced as the firm's new CEO.[84]

In 2020, the company sold its student loan portfolio.[85][86]

In May 2021, the company sold its Canadian Direct Equipment Finance business to Toronto-Dominion Bank.[87]

In 2021, the company sold its asset management division, Wells Fargo Asset Management (WFAM) to private equity firms GTCR and Reverence Capital Partners for $2.1 billion.[88] WFAM had $603 billion in assets under management as of December 31, 2020,[89][90] of which 33% was invested in money market funds.[91] WFAM was rebranded as Allspring Global Investments.[92][93]

Environmental record[edit]

In 2022, Wells Fargo announced a goal of reducing absolute emissions by companies it lends to in the oil and gas sector by 26% by 2030 from 2019 levels. Some critics say these goals conflict with the bank being the largest lender to fossil fuel companies in the U.S. and one of the largest globally.[94] The company has committed to net zero financed emissions by 2050; however, major environmental groups are skeptical if this goal will be achieved.[95] The company has stated that it will not finance any hydrocarbon exploration projects in the Arctic.[96] The company has also provided financing to renewable energy projects.

Wells Fargo History Museum[edit]

The company operates the Wells Fargo History Museum at 420 Montgomery Street, San Francisco. Displays include original stagecoaches, photographs, gold nuggets and mining artifacts, the Pony Express, telegraph equipment, and historic bank artifacts. The museum also has a gift shop.[97] In January 2015, armed robbers in an SUV smashed through the museum's glass doors and stole gold nuggets.[98][99][100][101] The company previously operated other museums but those have since closed.[102]

Lawsuits, fines, and controversies[edit]

Regulatory issues[edit]

The company has been the subject of several investigations by regulators. On February 2, 2018, the Wells Fargo account fraud scandal resulted in the Federal Reserve barring Wells Fargo from growing its nearly $2 trillion asset base any further until the company fixed its internal problems to the satisfaction of the Federal Reserve.[103] In September 2021, Wells Fargo incurred further fines from the United States Justice Department charging fraudulent behavior by the bank against foreign-exchange currency trading customers.[104] Bloomberg L.P. reported in March 2022 that Wells Fargo was the only major lender in 2020 to reject more home refinance applications from Black applicants than it approved.[105]

In December 2022, the U.S. levied a $3.7 billion loan-management fine upon Wells Fargo. In March 2023, Wells Fargo blamed a technical glitch for misstating the balances of customers' accounts, in many cases incorrectly deeming the customers as having a negative bank balance.[106] Subsequently, in 2023, prison sentencing took place for employee-directed money laundering and funneling cash illegally to Mexico through the creation of fictitious accounts.[107]

1981 MAPS Wells Fargo embezzlement scandal[edit]

In 1981, it was discovered that a Wells Fargo assistant operations officer, Lloyd Benjamin "Ben" Lewis, had perpetrated one of the largest embezzlements in history through its Beverly Drive branch. During 1978–1981, Lewis had successfully written phony debit and credit receipts to benefit boxing promoters Harold J. Smith (né Ross Eugene Fields) and Sam "Sammie" Marshall, chairman and president, respectively, of Muhammad Ali Professional Sports, Inc. (MAPS), of which Lewis was also listed as a director; Marshall, too, was a former employee of the same Wells Fargo branch as Lewis. In excess of $300,000 was paid to Lewis, who pled guilty to embezzlement and conspiracy charges in 1981, and testified against his co-conspirators for a reduced five-year sentence.[108] (Boxer Muhammad Ali had received a fee for the use of his name, and had no other involvement with the organization.[109])

Higher costs charged to African-American and Hispanic borrowers[edit]

Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan filed suit against Wells Fargo on July 31, 2009, alleging that the bank steered African Americans and Hispanics into high-cost subprime loans. A Wells Fargo spokesman responded that "The policies, systems, and controls we have in place – including in Illinois – ensure race is not a factor..."[110] An affidavit filed in the case stated that loan officers had referred to black mortgage-seekers as "mud people," and the subprime loans as "ghetto loans."[111] According to Beth Jacobson, a loan officer at Wells Fargo interviewed for a report in The New York Times, "We just went right after them. Wells Fargo mortgage had an emerging-markets unit that specifically targeted black churches because it figured church leaders had a lot of influence and could convince congregants to take out subprime loans." The report presented data from the city of Baltimore, where more than half the properties subject to foreclosure on a Wells Fargo loan from 2005 to 2008 now stand vacant, and 71 percent of those are in predominantly black neighborhoods.[111] Wells Fargo agreed to pay $125 million to subprime borrowers and $50 million in direct down payment assistance in certain areas, for a total of $175 million.[112][113][114]

Failure to monitor suspected money laundering[edit]

In a March 2010 agreement with US federal prosecutors, Wells Fargo acknowledged that between 2004 and 2007 Wachovia had failed to monitor and report suspected money laundering by narcotics traffickers, including the cash used to buy four planes that shipped a total of 22 tons of cocaine into Mexico.[115]

Overdraft fees[edit]

In August 2010, Wells Fargo was fined by United States district court judge William Alsup for overdraft practices designed to "gouge" consumers and "profiteer" at their expense, and for misleading consumers about how the bank processed transactions and assessed overdraft fees.[116][117] In May 2013, Wells Fargo paid $203 million to settle class-action litigation accusing the bank of imposing excessive overdraft fees on checking-account customers.[118]

Settlement and fines regarding mortgage servicing practices[edit]

On February 9, 2012, it was announced that the five largest mortgage servicers (Ally Financial, Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo) agreed to a settlement with the US Federal Government and 49 states over improper foreclosure practices in the 2010 United States foreclosure crisis, including "robo-signing" (having someone fraudulently sign that they know the contents of a document they do not in fact know) and foreclosing without standing via MERS.[119] The settlement, known as the National Mortgage Settlement (NMS), required the servicers to provide about $26 billion in relief to distressed homeowners and in direct payments to the federal and state governments; Wells Fargo's share was the second largest, at $5.4 billion.[120] This settlement amount makes the NMS the second largest civil settlement in U.S. history, only trailing the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.[121] The five banks were also required to comply with 305 new mortgage servicing standards. Oklahoma held out and agreed to settle with the banks separately.[122]

On April 5, 2012, a federal judge ordered Wells Fargo to pay $3.1 million in punitive damages over a single loan, one of the largest fines for a bank ever for mortgaging service misconduct, after the bank improperly charged Michael Jones, a New Orleans homeowner, with $24,000 in mortgage fees, after the bank misallocated payments to interest instead of principal. Elizabeth Magner, a federal bankruptcy judge in the Eastern District of Louisiana, cited the bank's behavior as "highly reprehensible", stating that Wells Fargo has taken advantage of borrowers who rely on the bank's accurate calculations.[123][124] The award was affirmed on appeal in 2013.[125]

In May 2013, New York attorney-general Eric Schneiderman announced a lawsuit against Wells Fargo over alleged violations of the national mortgage settlement. Schneidermann claimed Wells Fargo had violated rules over giving fair and timely serving.[126] In 2015, a judge sided with Wells Fargo.[127]

SEC fine due to inadequate risk disclosures[edit]

On August 14, 2012, Wells Fargo agreed to pay around $6.5 million to settle U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charges that in 2007 it sold risky mortgage-backed securities without fully realizing their dangers.[128]

Lawsuit by FHA over loan underwriting[edit]

In 2016, Wells Fargo agreed to pay $1.2 billion to settle allegations that the company violated the False Claims Act by underwriting over 100,000 Federal Housing Administration (FHA) backed loans when over half of the applicants did not qualify for the program.[129][130]

In October 2012, Wells Fargo was sued by United States Attorney Preet Bharara over questionable mortgage deals.[131]

[edit]

In April 2013, Wells Fargo settled a suit with 24,000 Florida homeowners alongside insurer QBE Insurance, in which Wells Fargo was accused of inflating premiums on forced-place insurance.[132]

Violation of New York credit card laws[edit]

In February 2015, Wells Fargo agreed to pay $4 million, including a $2 million penalty and $2 million in restitution for illegally taking an interest in the homes of borrowers in exchange for opening credit card accounts for the homeowners.[133]

Tax liability and lobbying[edit]

In December 2011, Public Campaign criticized Wells Fargo for spending $11 million on lobbying during 2008–2010, while increasing executive pay and laying off workers, while having no federal tax liability due to losses from the Great Recession.[134] However, in 2013, the company paid $9.1 billion in income taxes.[135]

Prison industry investment[edit]

The company has invested its clients' funds in GEO Group, a multi-national provider of for-profit private prisons.[136] By March 2012, its stake had grown to more than 4.4 million shares worth $86.7 million.[137] As of November 2012, Wells Fargo divested 33% of its holdings of GEO's stock, reducing its stake to 4.98% of Geo Group's common stock, below the threshold of which it must disclose further transactions.[138][139]

Discrimination against African Americans in hiring[edit]

In August 2020, the company agreed to pay $7.8 million in back wages for allegedly discriminating against 34,193 African Americans in hiring for tellers, personal bankers, customer sales and service representatives, and administrative support positions. The company agreed to provide jobs to 580 of the affected applicants.[140][141]

SEC settlement for insider trading case[edit]

In May 2015, Gregory T. Bolan Jr., a stock analyst at Wells Fargo agreed to pay $75,000 to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to settle allegations that he gave Joseph C. Ruggieri, a stock trader, insider information on probable ratings charges. Ruggieri was not convicted of any crime.[142][143][144]

Wells Fargo cross-selling scandal[edit]

In September 2016, Wells Fargo was issued a combined total of $185 million in fines for opening over 1.5 million checking and savings accounts and 500,000 credit cards on behalf of customers without their consent. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued $100 million in fines, the largest in the agency's five-year history, along with $50 million in fines from the City and County of Los Angeles, and $35 million in fines from the Office of Comptroller of the Currency.[145] The scandal was caused by an incentive-compensation program for employees to create new accounts. It led to the firing of nearly 5,300 employees and $5 million being set aside for customer refunds on fees for accounts the customers never wanted.[146] Carrie Tolstedt, who headed the department, retired in July 2016 and received $124.6 million in stock, options, and restricted Wells Fargo shares as a retirement package.[147][148]

On October 12, 2016, John Stumpf, the then chairman and CEO, announced that he would be retiring amidst the scandals. President and chief operating officer Timothy J. Sloan succeeded Stumpf, effective immediately. Following the scandal, applications for credit cards and checking accounts at the bank plummeted.[149] In response to the event, the Better Business Bureau dropped accreditation of the bank.[150][151] Several states and cities ended business relations with the company.[152]

An investigation by the Wells Fargo board of directors, the report of which was released in April 2017, primarily blamed Stumpf, who it said had not responded to evidence of wrongdoing in the consumer services division, and Tolstedt, who was said to have knowingly set impossible sales goals and refused to respond when subordinates disagreed with them. Wells Fargo coined the phrase, "Go for Gr-Eight" – or, in other words, aim to sell at least 8 products to every customer. The board chose to use a clawback clause in the retirement contracts of Stumpf and Tolstedt to recover $75 million worth of cash and stock from the former executives.[153]

In February 2020, the company agreed to pay $3 billion to settle claims by the United States Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission. The settlement did not prevent individual employees from being targets of future litigation.[154] The Federal Reserve put a limit to Wells Fargo's assets, as a result of the scandal. In 2020, Wells Fargo sold $100 million in assets to stay under the limit.[155]

In December 2022, the bank agreed to a settlement with the CFPB of $3.7 billion over abuses tied to the fake account scandal as well as mortgages and auto loans. The total was split between $1.7 billion for a civil penalty and $2 billion for customers.[156] Separately, in May 2023, the bank agreed to pay $1 billion to settle a shareholder class-action suit.[157]

Racketeering lawsuit for mortgage appraisal overcharges[edit]

In November 2016, Wells Fargo agreed to pay $50 million to settle allegations of overcharging hundreds of thousands of homeowners for appraisals ordered after they defaulted on their mortgage loans. While banks are allowed to charge homeowners for such appraisals, Wells Fargo frequently charged homeowners fees of $95 to $125 on appraisals for which the bank had been charged $50 or less. The plaintiffs had sought triple damages under the U.S. Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act on grounds that sending invoices and statements with fraudulently concealed fees constituted mail and wire fraud sufficient to allege racketeering.[158]

Financing of Dakota Access Pipeline[edit]

Wells Fargo is a lender on the Dakota Access Pipeline, a 1,172-mile-long (1,886 km) underground oil pipeline transport system in North Dakota. The pipeline has been controversial regarding its potential impact on the environment.[159]

In February 2017, the city councils of Seattle, Washington and Davis, California voted to move $3 billion of deposits from the bank due to its financing of the Dakota Access Pipeline as well as the Wells Fargo account fraud scandal.[160]

Failure to comply with document security requirements[edit]

In December 2016, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority fined Wells Fargo $5.5 million for failing to store electronic documents in a "write once, read many" format, which makes it impossible to alter or destroy records after they are written.[161]

Doing business with the gun industry and NRA[edit]

From December 2012 through February 2018, Wells Fargo reportedly helped two of the biggest firearms and ammunition companies obtain $431.1 million in loans.[162] It also handled banking for the National Rifle Association of America (NRA) and provided bank accounts and a $28-million line of credit.[162] In 2020, the company said that it is winding down its business with the NRA.[163]

Discrimination against female workers[edit]

In June 2018, about a dozen female Wells Fargo executives from the wealth management division met in Scottsdale, Arizona to discuss the minimal presence of women occupying senior roles within the company. The meeting, dubbed "the meeting of 12", represented the majority of the regional managing directors, of which 12 out of 45 were women.[164] Wells Fargo had previously been investigating reports of gender bias in the division in the months leading up to the meeting.[165] The women reported that they had been turned down for top jobs despite their qualifications, and instead the roles were occupied by men.[165] There were also complaints against company president Jay Welker, who is also the head of the Wells Fargo wealth management division, due to his sexist statements regarding female employees. The female workers claimed that he called them "girls" and said that they "should be at home taking care of their children."[165][166]

Overselling auto insurance[edit]

On June 10, 2019, Wells Fargo agreed to pay $385 million to settle a lawsuit accusing it of allegedly scamming millions of auto-loan customers into buying insurance they did not need from National General Insurance.[167]

Failure to Supervise Registered Representatives[edit]

On August 28, 2020, Wells Fargo agreed to pay a fine of $350,000 as well as $10 million in restitution payments to certain customers after the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority accused the company of failing to reasonably supervise two of its registered representatives that recommended that customers invest a high percentage of their assets in high-risk energy securities in 2014 and 2015.[168]

Steering customers to more expensive retirement accounts[edit]

In April 2018, the United States Department of Labor launched a probe into whether Wells Fargo was pushing its customers into more expensive retirement plans as well as into retirement funds managed by Wells Fargo itself.[169][170]

Alteration of documents[edit]

In May 2018, the company discovered that its business banking group had improperly altered documents about business clients in 2017 and early 2018.[171]

Executive compensation[edit]

With CEO John Stumpf paid 473 times more than the median employee, Wells Fargo ranked number 33 among the S&P 500 companies for CEO—employee pay inequality. In October 2014, a Wells Fargo employee earning $15 per hour emailed the CEO—copying 200,000 other employees—asking that all employees be given a $10,000 per year raise taken from a portion of annual corporate profits to address wage stagnation and income inequality. After being contacted by the media, Wells Fargo responded that all employees receive "market competitive" pay and benefits significantly above US federal minimums.[172][173]

Pursuant to Section 953(b) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, publicly traded companies are required to disclose (1) the median total annual compensation of all employees other than the CEO and (2) the ratio of the CEO's annual total compensation to that of the median employee.[174]

Aggressive freezing and closing of bank accounts[edit]

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that between 2011 and 2016, Wells Fargo had been freezing entire consumer deposit accounts based on automated fraud detection. This freeze extended to the entire account, not just the suspicious amount, and all access to funds was blocked. As a result, customers were unable to access their funds until the accounts were closed and the funds were returned. In 2022, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau mandated that Wells Fargo provide $160 million in compensation to more than a million individuals, addressing the significant harm caused by its aggressive tactic of freezing and closing bank accounts during the period from 2011 to 2016.[175]

In popular culture[edit]

The company was a theme or the subject in a few films. In the 1939 John Ford-directed movie "Stagecoach", at the 5:22 mark two men can be seen hoisting a chest plainly marked "Wells Fargo." Seven Men from Now (a 1956 film), Cheyenne (the 1947 film), Wells Fargo (a 1937 film) and Unclaimed Goods (a 1918 silent) are examples. A long running television series, Tales of Wells Fargo ran from 1957 to 1962, focusing on a fictitious Wells Fargo special agent.

Wells Fargo stagecoaches are mentioned in the song "The Deadwood Stage (Whip-Crack-Away!)" in the 1953 film Calamity Jane performed by Doris Day: "With a fancy cargo, care of Wells and Fargo, Illinois - Boy!".[176] Wells Fargo is also shown as the delivery service bringing the instruments for the town band in the 1962 film The Music Man. A Wells Fargo & Company stagecoach is seen passing through the town of Hill Valley as Marty is walking down the street in the 1990 film, Back to the Future Part III.

The song "The Wells Fargo Wagon" is part of the Broadway musical The Music Man, referring to Wells, Fargo & Company's stagecoach delivery in the early 20th century, the time in which The Music Man is set.

Charity[edit]

On March 2, 2022, Wells Fargo announced $1 million donation to the American Red Cross that will be used for Ukrainian refugees fleeing from the Russian invasion.[177]

In April 2022, The Wells Fargo foundation announced its pledge of $210 million toward racial equity in homeownership. With $60 million of the donation awarded in Wealth Opportunities Restored through Homeownership (WORTH) grants which will run until 2025. Additionally, $150 million will be committed to lower mortgage rates and reducing the refinancing costs to aid minority homeowners.[178]

In April 2023, TD Jakes Group and Wells Fargo have formalized a 10-year partnership to create inclusive communities for people of all income levels. Wells Fargo has committed approximately $1 billion to fund projects that align with the overall strategy. The first of the projects focuses on the development of mixed-income housing and retail facilities outside of Atlanta.[179]

In December 2023, Wells Fargo appointed Darlene Goins as president of the Wells Fargo Foundation and Head of Philanthropy and Community Impact. Previously, she had held leadership roles at FICO, a leading data and analytics company, and at Wells Fargo, she was responsible for helping low-income populations as head of philanthropy for financial health. She also led the Banking Inclusion Initiative, a 10-year commitment to help people access low-cost basic accounts and help those without bank accounts gain easy access to low-cost banking services and financial education.[180]

See also[edit]

- List of Wells Fargo directors

- List of Wells Fargo presidents

- Wells Fargo Arena

- Wells Fargo Center

- Big Four banks

References[edit]

- ^ a b Rouse v. Wachovia Mortgage, FSB, 747 F.3d 707 (9th Cir. 2014) (citing cases on each side of circuit split and joining majority rule that a national bank is only a citizen of the state in which its main office is located).

- ^ a b "Newsroom Wells Fargo Announces Expansion at Hudson Yards". New York: Wells Fargo. November 27, 2023. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ a b Wack, Kevin (February 26, 2020). "How New York became Wells Fargo's new center of power". American Banker.

- ^ a b "Wells Fargo Manhattan Headquarters". Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Wells Fargo & Company Annual Report 2022" (PDF). wellsfargo.com. Wells Fargo.

- ^ O'Daniel, Adam (November 1, 2012). "Wells Fargo to open new Charlotte trading floor in Duke Energy Center". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "PHOTOS: First look at Wells Fargo Securities' new trading floor". American City Business Journals. November 29, 2012.

- ^ Wack, Kevin (February 26, 2020). "How New York became Wells Fargo's new center of power". American Banker.

- ^ "FRB: Large Commercial Banks".

- ^ Fox, Zach; Gull, Zuhaib (July 16, 2020). "Quicken overtakes Wells Fargo as nation's No. 1 mortgage originator". S&P Global.

- ^ Gray, Melinda (February 7, 2014). "Wells Fargo Tops List of World's Most Valuable Bank Brands". Chicago Agent.

- ^ "The Top 500 Banking Brands, 2014". The Banker. February 3, 2014.

- ^ "Fortune 500: Wells Fargo". Fortune.

- ^ Tayan, Brian (December 19, 2016). "The Wells Fargo Cross-Selling Scandal". Harvard Law School.

- ^ Egan, Matt (January 13, 2017). "Wells Fargo dumps toxic 'cross-selling' metric". CNN.

- ^ Smith, Randall (February 28, 2011). "In Tribute to Wells, Banks Try the Hard Sell". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Touryalai, Halah (January 25, 2012). "The Art Of The Cross-Sell". Forbes.

- ^ "International Locations". January 12, 2024.

- ^ "Why US banking giant Wells Fargo is creating back-office jobs in India". Firstpost. June 22, 2012.

- ^ Babal, Marianne (March 14, 2019). "Charter Number 1". Wells Fargo.

- ^ Rivera, Sheila (2004). California Gold Rush. Edina, Minnesota: ABDO. p. 32. ISBN 1-59197-281-7.

- ^ Ely, Glen Sample (2016). The Texas Frontier and the Butterfield Overland Mail, 1858–1861. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-8061-5221-9.

- ^ "Butterfield Overland Mail". California State Parks.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Investment Advisors", Macmillan Guide to International Asset Managers, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 276–280, 1989, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-10905-0_67, ISBN 978-1-349-10907-4, retrieved November 15, 2023

- ^ Engstrand, Iris. "Wells Fargo: California's Pioneer Bank" (PDF). San Diego History.

- ^ "Enlisting the stagecoach during WWI". Wells Fargo. June 29, 2018.

- ^ "Wells and Fargo start shipping and banking company". History.com.

- ^ "A Salute to the Society's Corporate Patrons: Wells Fargo Bank, N.a." Southern California Quarterly. 66 (4): 377–378. 1984. doi:10.2307/41171130. JSTOR 41171130.

- ^ "Wells Fargo, American Trust Merge as the 11th Biggest Bank". The New York Times. March 26, 1960.

- ^ Kovner, Guy (February 12, 2015). "Santa Rosa power broker, philanthropist Henry Trione dies at 94". The Press Democrat.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Bank Is Given Holding Company Approval". The New York Times. January 31, 1969.

- ^ Calderón, Fernando Herrera (2021). Twentieth Century Guerrilla Movements in Latin America: A Primary Source History. Oxon: Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-415-73179-9.

- ^ MAHONY, EDMUND H. (February 29, 2008). "NOT GUILTY PLEA IN 1983 ARMED ROBBERY". Hartford Courant.

- ^ Madden, Richard L. (December 11, 1983). "WELLS FARGO THEFT, 3 MONTHS LATER: ONLY TANTALIZING LEADS TO $7 MILLION". The New York Times.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (May 31, 1986). "CROCKER ABSORBED INTO WELLS FARGO". The New York Times.

- ^ Gruber, William (February 8, 1986). "WELLS FARGO BUYS CROCKER". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Wells Fargo & Company 1987 Annual Report" (PDF).

- ^ Lawrence M. Fisher (January 16, 1988). "Wells Fargo to Buy Barclays in California". The New York Times.

- ^ "Regulators seize Great American Bank". United Press International. August 9, 1991.

- ^ Hansell, Saul (January 25, 1996). "Wells Fargo Wins Battle for First Interstate". The New York Times.

- ^ Baker, David R. (December 19, 2004). "When hostile takeovers backfire". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Svaldi, Aldo (June 12, 1998). "Wells Fargo learned hard way about deals". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "Wow! Two decades of banking online". Wells Fargo. May 18, 2015.

- ^ "Wells Fargo, Norwest pair". CNN. June 8, 1998.

- ^ O'Brien, Timothy L. (June 9, 1998). "Wells Fargo And Norwest Plan Merger". The New York Times.

- ^ "Wells Fargo to Buy Alaskan Bank". Los Angeles Times. December 22, 1999.

- ^ "H.D. Vest to be acquired by Internet company Blucora for $580 million". Investment News. October 15, 2015.

- ^ "Wells Fargo, Greater Bay Bancorp Agree to Merge" (Press release). PR Newswire. May 4, 2007.

- ^ Said, Carolyn (May 5, 2007). "Wells Fargo buys bank / Greater Bay has 41 branches in the Bay Area". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Gobbles Up Greater Bay Bancorp". The New York Times. May 7, 2007.

- ^ Barris, Mike (May 4, 2007). "Wells Fargo Agrees to Acquire Greater Bay Bancorp for $1.5 Billion". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Wells Fargo to purchase Placer Sierra Bank, owner of four Bank of Lodi branches". Lodi News-Sentinel. January 9, 2007.

- ^ "Wells Fargo to Purchase CIT Unit". American Banker. June 22, 2007.

- ^ Stempel, Jonathan (June 22, 2007). "Wells Fargo to buy CIT Group's construction unit". Reuters.

- ^ "Wells to acquire United Bancorp of Wyoming". American City Business Journals. January 15, 2008.

- ^ Chad Eric Watt (August 13, 2008). "Wells Fargo to acquire Century Bank". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "Wells Fargo agrees to buy Wachovia; Citi objects". USA Today. Associated Press. October 4, 2008.

- ^ "Court tilts Wachovia fight toward Wells". WABC-TV. October 5, 2008.

- ^ "Court tilts Wachovia fight toward Wells Fargo". Times Internet. October 6, 2008.

- ^ "Wells Fargo plans to buy Wachovia; Citi ends talks". USA Today. Associated Press. October 9, 2008.

- ^ "Capital Purchase Program Transaction Report" (PDF). Transactions Report (Troubled Asset Relief Program). November 17, 2008.

- ^ Landler, Mark & Dash, Eric (October 15, 2008). "Drama Behind a $250 billion Banking Deal". The New York Times.

- ^ Temple, James (May 9, 2009). "Wells Fargo stock offering raises $8.6 billion". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Barr, Alistair (December 23, 2009). "Citigroup and Wells Fargo exit TARP". MarketWatch.

- ^ "Wells Fargo buys North Coast Surety Insurance". American City Business Journals. April 20, 2009.

- ^ Pfeuti, Elizabeth (November 23, 2010). "Fund administration giant buys Cayman rival; Asset managers are returning to the offshore domicile after retreating in the aftermath of the Crisis". Financial News.

- ^ Ahmed, Azam (August 15, 2011). "Wells Fargo Brings Citadel's Investment Banking Unit Aboard". The New York Times.

- ^ Moyer, Liz; Rieker, Matthias (August 16, 2011). "Wells Fargo Scores Citadel Investment-Bank Talent, Deals". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Touryalai, Halah (August 16, 2011). "Don't Read Too Much Into Wells Fargo's Deal With Citadel". Forbes.

- ^ "Wells Fargo to Acquire Merlin Securities, LLC" (Press release). Business Wire. April 27, 2012.

- ^ "Wells Fargo to Buy Prime Brokerage Firm". The New York Times. April 27, 2012.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Rebrands Merlin Securities to Wells Fargo Prime Services" (Press release). Business Wire. December 3, 2012.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Announces the Sale of Its Majority Stake in The Rock Creek Group" (Press release). Business Wire. July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Agrees to Acquire GE's Railcar Leasing Business". Bloomberg News. September 30, 2015.

- ^ Koren, James Rufus (October 14, 2015). "Wells Fargo buys 3 GE units focused on equipment financing". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Dillet, Romain (March 27, 2017). "Wells Fargo will let you use Apple Pay and Android Pay to withdraw money". TechCrunch.

- ^ Levitt, Hannah (June 5, 2018). "Wells Fargo sells all its branches in Indiana, Michigan, Ohio". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Egan, Matt (June 5, 2018). "Wells Fargo sells all its branches in three Midwestern states". CNN.

- ^ Moise, Imani (June 5, 2018). "Wells Fargo pulls back from U.S. Midwest, selling 52 branches to Flagstar". Reuters.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Plans To Eliminate Up To 26,450 Jobs By 2020". HuffPost. Reuters. September 21, 2018.

- ^ Egan, Matt (September 20, 2018). "Wells Fargo plans to cut up to 26,500 jobs over three years". CNN.

- ^ LIBERTO, JENNIFER (March 28, 2019). "Wells Fargo CEO Quits In Wake Of Consumer Financial Scandals". NPR.

- ^ "Principal Completes Acquisition of Wells Fargo Institutional Retirement & Trust Business" (Press release). Principal Financial Group. July 1, 2019.

- ^ Egan, Matt (September 27, 2019). "Wells Fargo names financial veteran Charles Scharf as its new CEO". CNN.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Agrees to Sell Private Student Loan Portfolio" (Press release). Business Wire. December 18, 2020.

- ^ Truong, Kevin (December 21, 2020). "Wells Fargo sells off private student loan business". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "TD Bank Group completes acquisition of Wells Fargo's Canadian Direct Equipment Finance Business" (Press release). Toronto-Dominion Bank. May 3, 2021.

- ^ French, David; Hussain, Noor (February 23, 2021). "Wells Fargo sells asset management arm to private equity firms for $2.1 billion". Reuters.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Enters Agreement with GTCR and Reverence Capital Partners to Sell Wells Fargo Asset Management" (Press release). Wells Fargo. February 23, 2021.

- ^ "Wells Fargo sells asset management arm to private-equity firms for $2.1 billion". CNBC. Reuters. February 23, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Sophie; Comtois, James (March 11, 2021). "Wells Fargo unit sale hailed as opportunity". Pensions & Investments.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Closed-End Funds Announce Change of Name" (Press release). Business Wire. July 26, 2021.

- ^ Segal, Julie (July 26, 2021). "Wells Fargo Asset Management to Get New CEO and New Brand". Institutional Investor.

- ^ Marshall, Elizabeth Dilts; Kerber, Ross (May 6, 2022). "Wells Fargo set emissions reduction targets for oil, gas, power clients". Reuters.

- ^ "Wells Fargo makes net zero commitment but does not rule out continued financing of fossil fuels". BankTrack. March 8, 2021.

- ^ Bleir, Garet (March 3, 2020). "Wells Fargo, Top Banker of Fracked Oil and Gas, Ditches Arctic Drilling". Sierra Club.

- ^ "Museum - Wells Fargo History". Wells Fargo.

- ^ Calvey, Mark (February 19, 2015). "Wells Fargo History Museum reopens after gold heist". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "PHOTOS: Robbery at San Francisco's Wells Fargo Museum". KGO-TV. January 29, 2015.

- ^ Glazer, Emily (January 27, 2015). "Gold Nuggets Stolen From Wells Fargo Museum in San Francisco". The Wall Street Journals.

- ^ CORKERY, MICHAEL (January 27, 2015). "Robbers Crash Into Wells Fargo Museum to Steal Gold Nuggets". The New York Times.

- ^ Hudson, Caroline (September 2, 2020). "Wells Fargo to permanently shutter almost all of its museums". American City Business Journals.

- ^ Flitter, Emily; Appelbaum, Binyamin; Cowley, Stacy (February 2, 2018). "Federal Reserve Shackles Wells Fargo After Fraud Scandal". The New York Times.

- ^ Son, Hugh (September 27, 2021). "Wells Fargo pays $37 million to resolve Justice Department claims it defrauded currency customers". CNBC. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Donnan, Shawn; Choi, Ann; Levitt, Hannah; Cannon, Christopher (March 11, 2022). "Wells Fargo Rejected Half Its Black Applicants in Mortgage Refinancing Boom". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Collette Bennett (March 10, 2023). "Wells Fargo Just Made Another Huge Mistake". The Street. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

The controversial bank is trending yet again.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Personal Banker Sentenced for Money Laundering and Bank Fraud". United States Department of Justice. March 2, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ Miller, Wilbur R.The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia, SAGE Publications, 2012, page 666. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (February 1, 1981). "Sports of The Times; The Maps Boxing Scandal". The New York Times.

- ^ "Illinois Files Bias Suit Against Wells Fargo". Reuters. July 31, 2009.

- ^ a b Powell, Michael (June 7, 2009). "Bank Accused of Pushing Mortgage Deals on Blacks". The New York Times.

- ^ Broadwater, Luke (July 13, 2012). "Wells Fargo agrees to pay $175M settlement in pricing discrimination suit". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Yost, Pete (July 13, 2012). "Wells Fargo settles discrimination case". Associated Press.

- ^ "Justice Department Reaches Settlement with Wells Fargo Resulting in More Than $175 Million in Relief for Homeowners to Resolve Fair Lending Claims" (Press release). United States Department of Justice. July 12, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Michael (June 29, 2010). "Banks Financing Mexico Gangs Admitted in Wells Fargo Deal". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Gelles, Jeff (August 15, 2010). "Consumer 10.0: How Wells Fargo held up debit-card customers". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ "Wells Fargo loses consumer case over overdraft fees". Los Angeles Times. Bloomberg News. August 10, 2010.

- ^ Stempel, Jonathan (May 15, 2013). "Wells Fargo ordered to pay $203 million in overdraft case". Reuters.

- ^ "Joint State-Federal Mortgage Servicing Settlement FAQ". National Mortgage Settlement.

- ^ New York Times, Mortgage Plan Gives Billions to Homeowners, but With Exceptions, February 9, 2012

- ^ Schwartz, Nelson D.; Creswell, Julie (February 10, 2012). "Mortgage Plan Gives Billions to Homeowners, but With Exceptions". The New York Times.

- ^ "Did Oklahoma A.G. Scott Pruitt, Mortgage Settlement Holdout, Sell Out His State for Wall Street?". February 9, 2012.

- ^ Hallman, Ben (September 4, 2012). "Wells Fargo Slapped With $3.1 Million Fine For 'Reprehensible' Handling Of One Mortgage". HuffPost.

- ^ GAROFALO, PAT (April 10, 2012). "Judge Blasts Wells Fargo's 'Reprehensible' Actions, Awards Homeowner $3 Million". ThinkProgress.

- ^ "Jones v. Wells Fargo Home Mortg., Inc". March 19, 2013.

- ^ Isidore, Chris (October 2, 2013). "Wells Fargo charged with violating mortgage deal". CNN.

- ^ Viswanatha, Aruna; Freifeld, Karen (February 2, 2015). "Judge rules for Wells Fargo in NY challenge over mortgage settlement". Reuters.

- ^ Blumenthal, Jeff (August 14, 2012). "Wells Fargo paying $6.5M to settle charges with SEC". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Bank Agrees to Pay $1.2 Billion for Improper Mortgage Lending Practices" (Press release). United States Department of Justice. April 8, 2016.

- ^ Raice, Shayndi (October 10, 2012). "U.S. Sues Wells Fargo for Faulty Mortgages". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "U.S. Accuses Bank of America of a 'Brazen' Mortgage Fraud". The New York Times. October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Wells Fargo, QBE Agree on $19.3M Force-Placed Settlement". Property Casualty 360. May 17, 2013.

- ^ Freifeld, Karen (February 5, 2015). "Wells Fargo to pay $4 million for violations on credit card accounts: New York". Reuters.

- ^ Portero, Ashley. "30 Major U.S. Corporations Paid More to Lobby Congress Than Income Taxes, 2008–2010". International Business Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012.

- ^ McIntyre, Douglas (March 17, 2013). "Companies paying the most in income taxes". USA Today.

- ^ Dolan, Eric W. (November 10, 2011). "Wells Fargo takes heat over investments in private prison industry". The Raw Story. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012.

The advocacy group Small Business United on Thursday called on Wells Fargo to provide a full accounting of investments related to private prisons and immigrant detention centers.

- ^

Greenwald, Glenn (April 12, 2012). "Wells Fargo's prison cash cow". Salon.com.

The bailed-out bank has used its taxpayer money to invest in private prisons.

- ^ "CORRECTION: Wells Fargo Dumps 33% of Geo Group Stock". pcasc. October 25, 2012.

- ^ "CORRECTION: WELLS FARGO PRIVATE PRISON DIVESTMENT". Prison Industry Divestment Movement. November 2, 2012.

- ^ "WELLS FARGO AGREES TO PAY $7.8 MILLION IN BACK WAGES AFTER U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR ALLEGES HIRING DISCRIMINATION". United States Department of Labor. August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Wells Fargo to Pay $7.8 Million to Settle Hiring Bias Claims" Paige Smith, Bloomberg Law, August 24, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Armental, Maria (September 14, 2015). "Insider-Trading Charges Against Former Wells Fargo Trader Dismissed". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Raymond, Nate (September 14, 2015). "Update: 2-Ex-Wells Fargo trader beats SEC insider trading charges". Reuters.

- ^ "Ex-Wells Fargo Analyst Settles Insider Trading Case". Law360. May 28, 2015.

- ^ "Wells Fargo fined $185M for fake accounts; 5,300 were fired". USA Today. September 8, 2016.

- ^ Glazer, Emily (September 9, 2016). "Wells Fargo Fined for Sales Scam". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660.

- ^ Gandel, Stephen (September 12, 2016). "Wells Fargo Exec Who Headed Phony Accounts Unit Collected $125 Million". Fortune.

- ^ Corkery, Michael (September 20, 2016). "Illegal Activity at Wells Fargo May Have Begun Earlier, Chief Says". The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ Roberts, Deon. "Wells Fargo reveals latest post-scandal customer traffic numbers". Charlotte Observer.

- ^ Cox, Jeff (October 20, 2016). "Wells Fargo just lost its accreditation with the Better Business Bureau". CNBC.

- ^ Procter, Richard (October 12, 2016). "Wells Fargo loses Better Business Bureau accreditation, which could take years to regain". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "Massachusetts latest to bar Wells Fargo as underwriter". Reuters. October 18, 2016.

- ^ Cowley, Stacy; Kingson, Jennifer A. (April 10, 2017). "Wells Fargo to Claw Back $75 Million From 2 Former Executives". The New York Times.

- ^ Egon, Matt (February 22, 2020). "US government fines Wells Fargo $3 billion for its 'staggering' fake-accounts scandal". CNN.

- ^ Steinberg, Julie; Eisen, Ben (July 31, 2020). "Wells Fargo Sold Assets to Stay Under Fed Asset Cap as Markets Lurched". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Son, Hugh (December 20, 2022). "Wells Fargo agrees to $3.7 billion settlement with CFPB over consumer abuses". CNBC. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- ^ Eisen, Ben (May 15, 2023). "Wells Fargo Agrees to Pay Shareholders $1 Billion to Settle Class-Action Suit". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Aubin, Dena (October 31, 2016). "Wells Fargo agrees to $50 million settlement over homeowner fees". Reuters.

- ^ Fuller, Emily (September 29, 2016). "How to Contact the 17 Banks Funding the Dakota Access Pipeline". YES! Magazine.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (February 8, 2017). "2 Cities To Pull More Than $3 Billion From Wells Fargo Over Dakota Access Pipeline".

- ^ "FINRA fines Wells Fargo, others $14 mln for records' changeable format". Reuters. December 21, 2016. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Wells Fargo is the top banker for the NRA and gunmakers". Los Angeles Times. Bloomberg News. March 7, 2018. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018.

- ^ Moise, Imani (April 28, 2020). "Wells Fargo's relationship with NRA is 'declining': CEO". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 28, 2020.

- ^ Glazer, Emily (August 31, 2018). "At Wells Fargo, Discontent Simmers Among Female Executives". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660.

- ^ a b c Rooney, Kate (August 31, 2018). "Wells Fargo said to be investigating reports of gender bias in its wealth division". CNBC.

- ^ Glazer, Emily (August 31, 2018). "At Wells Fargo, Discontent Simmers Among Female Executives". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Hudson, Caroline (June 10, 2019). "Wells Fargo agrees to $385M settlement for auto insurance scheme". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "FINANCIAL INDUSTRY REGULATORY AUTHORITY LETTER OF ACCEPTANCE, WAIVER AND CONSENT NO. 2015045713304" (PDF). August 28, 2021.

- ^ Morgenson, Gretchen; Glazer, Emily (April 26, 2018). "Wells Fargo's 401(k) Practices Probed by Labor Department". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Rooney, Kate (April 26, 2018). "Labor Department is reportedly investigating Wells Fargo's 401(k) unit". CNBC.

- ^ Egan, Matt (May 17, 2018). "Wells Fargo altered documents about business clients". CNN.

- ^ Short, Kevin (October 9, 2014). "Wells Fargo Employee Calls Out CEO's Pay, Requests Company-Wide Raise In Brave Email". HuffPost.

- ^ Schafer, Leo (October 15, 2014). "Schafer: Wells Fargo missed mark after worker requested $10,000 raises for all". Star Tribune.

- ^ "H.R.4173 - Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act". Congress.gov.

- ^ "2022-CFPB-0011_Wells Fargo Bank N.A. - Consent Order"

- ^ "Deadwood Stage (Whip Crack Away, Calamity Jane) Lyrics". lyricsfreak.com.

- ^ Amiah Taylor (March 7, 2022). "Google transforms Poland office into help center for Ukrainian refugees". Fortune. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "Wells Fargo commits $210 million toward racial equity in homeownership". Philanthropy News Digest. April 15, 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ "T.D. Jakes Group, Wells Fargo join forces for 10-year partnership promoting inclusive communities". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 18, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "Wells Fargo Names Darlene Goins Head of Philanthropy and Community Impact, President of Wells Fargo Foundation". Businesswire. Archived from the original on December 10, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Business data for Wells Fargo & Co:

- Wells Fargo

- 1852 establishments in New York (state)

- American companies established in 1852

- Banks based in California

- Banks established in 1852

- Companies based in San Francisco

- Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange

- Financial District, San Francisco

- Mortgage lenders of the United States

- Online brokerages

- Systemically important financial institutions