Vladimir Petrov (diplomat)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

Vladimir Petrov | |

|---|---|

Владимир Миха́йлович Петров | |

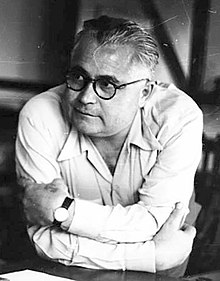

Vladimir Petrov in a safe house after defecting to Australia. | |

| Born | Afanasy Mikhaylovich Shorokhov 15 February 1907 Larikha, Siberia, Russian Empire |

| Died | 14 June 1991 (aged 84) Melbourne, Australia |

| Other names | Vladimir Mikhaylovich Proletarsky |

| Spouse | Evdokia Petrova |

Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov (Russian: Влади́мир Миха́йлович Петро́в; 15 February 1907 – 14 June 1991) was a member of the Soviet Union's clandestine services who became famous in 1954 for his defection to Australia.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

He was born Afanasy Mikhaylovich Shorokhov (Russian: Афанасий Миха́йлович Шорохов), into a peasant family in the village of Larikha, in central Siberia.

Petrov joined the Komsomol in 1923 and the Soviet Navy.[citation needed], changing his full name to Vladimir Mikhaylovich Proletarsky (Russian: Влади́мир Миха́йлович Пролетарский).

Intelligence career[edit]

According to his recently released secret British MI5 file, Petrov stated during his post-defection interviewing that his intelligence career was as follows:

- 1929–1933 cypher clerk Soviet Navy.

- 1933–1938 NKVD Moscow dealing with overseas cypher communications.

- 1939 NKVD cypher clerk attached to Soviet Army Western China.

- 1940–1942 NKVD cypher clerk Moscow dealing with Internal communications.

- 1942–1947 NKVD cypher clerk Sweden with additional Internal Security duties.

- 1947–1951 MGB Moscow dealing with seamen on the Danube.

- 1951–1954 MGB controller in Australia.

Petrov also gave information about the defection of Burgess and Maclean of the Cambridge Five. Their escape had been handled by Kislitsyn, an MGB officer who was in Australia when Petrov defected in 1954. Petrov also disclosed that Burgess and Maclean were living in Kuibyshev in 1954. (National Archives Reference:kv/2/3440)

Joining OGPU[edit]

He decided to join the Soviet spy organization, the OGPU, in May 1933. He was subsequently admitted to the Special Cipher Section, which was attached to the Foreign Department of the OGPU. It was his status in this section which allowed him to learn many Soviet secrets by reading the top secret ciphers.

Petrov lived through the purges of Stalin under Yagoda, Yezhov, and Beria. Even though a great number of his friends, colleagues, and superiors were arrested and executed, Petrov escaped unscathed.[1]

Australia and defection[edit]

Having graduated from cipher clerk to full-fledged agent, Petrov was sent to Australia by the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD)[citation needed] in 1951. His job there was to recruit spies and to keep watch on Soviet citizens, making sure that none of the Soviets abroad defected. Ironically, it was in Australia where events would occur which led to his own defection from the Soviet Union. This came about through his association with Polish-born doctor and musician Michael Bialoguski, who played along in seeming to allow Petrov to recruit him to gather information, while at the same time reporting to Australian Security Intelligence Organisation on Petrov's activities.

Petrov applied for political asylum in 1954, on the grounds that he could provide information regarding a Soviet spy ring operating out of the Soviet Embassy in Australia. Petrov states in his memoirs (ghost written by Michael Thwaites) that his reasoning for defecting lay not in an imminent fear of being executed, but in his disillusionment with the Soviet system and his own experiences and knowledge of the terror and human suffering inflicted on the Soviet people by their government. He witnessed the destruction of the Siberian village in which he was born, caused by forced collectivization and the famine which resulted.

Life after defection[edit]

Vladimir Petrov became an Australian citizen in 1956. The Petrovs bought a home in Bentleigh, Melbourne, in the same year. He and his wife Evdokia's names were changed to Sven and Anna Allyson to protect their identities. They lived a quiet suburban life in Melbourne.[2] He died in 1991, and she died in 2002.

They were protected under the D-notice system. Although the press agreed not to identify them under the D-notice, the press did not always observe this voluntary protection order. The whereabouts of the Petrovs were still the subject of a D-Notice in 1982.[3][4]

Fictional representations[edit]

Petrov's defection has inspired fictional works.

- The Case of Colonel Petrov (1956) for American television

- Defection! The Case of Colonel Petrov (1966) for British television

- The Red Shoe, a novel by Ursula Dubosarsky which won the New South Wales Premier's Literary Award and the Queensland Premier's Literary Award in 2006.[5]

- Mrs Petrov's Shoe, a play by Noelle Janaczewska which won the Queensland Premier's Literary Award for drama in 2006.[5]

- The Safe House, an animation by Lee Whitmore, narrated by Noni Hazelhurst, which won Best Animation at the Sydney Film Festival 2006.[6]

- Document Z, a novel by Andrew Croome, which won the Australian/Vogel Literary Award in 2008.[7]

- The Petrov Affair, a 1987 television mini-series.[8]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Stalin purges". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Stephens, Tony (27 July 2002). "Spies who loved us". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Sadler, Pauline (May 2000). "The D-Notice System". Press Council News. 12 (2). Archived from the original on 11 March 2004.

- ^ "D Notices – Fact sheet 49 – National Archives of Australia". Naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Queensland Premier's Literary Awards: Previous winners". Queensland Government. 30 November 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ "The Safe House". leewhitmore.com.au. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ Neill, Rosemary (22 April 2011). "Fully formed: 30 years of The Australian/Vogel Literary Award". The Australian. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ Menglet, Alex; Sitta, Eva; Chilvers, Simon; Picot, Geneviève (27 May 1987), The Petrov Affair, retrieved 2 April 2017

Further reading[edit]

- Petrov, Vladimir Mikhaĭlovich; Petrov, Evdokia (1 January 1956). Empire of Fear. Praeger. OCLC 170859.