Visual music

Visual music, sometimes called color music, refers to the creation of a visual analogue to musical form by adapting musical structures for visual composition, which can also include silent films or silent Lumia work. It also refers to methods or devices which can translate sounds or music into a related visual presentation. An expanded definition may include the translation of music to painting; this was the original definition of the term, as coined by Roger Fry in 1912 to describe the work of Wassily Kandinsky.[1] There are a variety of definitions of visual music, particularly as the field continues to expand. In some recent writing, usually in the fine art world, visual music is often confused with or defined as synaesthesia, though historically this has never been a definition of visual music. Visual music has also been defined as a form of intermedia.

Visual music also refers to systems which convert music or sound directly into visual forms, such as film, video, computer graphics, installations or performances by means of a mechanical instrument, an artist's interpretation, or a computer. The reverse is applicable also, literally converting images to sound by drawn objects and figures on a film's soundtrack, in a technique known as drawn or graphical sound. Famous visual music artists include Mary Ellen Bute, Jordan Belson, Oskar Fischinger, Norman McLaren, John Whitney Sr., and Thomas Wilfred, plus a number of contemporary artists.

Instruments[edit]

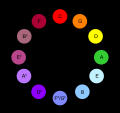

The history of this tradition includes many experiments with color organs. Artist or inventors "built instruments, usually called 'color organs,' that would display modulated colored light in some kind of fluid fashion comparable to music".[2] For example, the Farblichtspiele ('colored-light-plays') of former Bauhaus student Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack. Several different definitions of color music exist; one is that color music is generally formless projections of colored light. Some scholars and writers have used the term color music interchangeably with visual music.

The construction of instruments to perform visual music live, as with sonic music, has been a continuous concern of this art. Color organs, while related, form an earlier tradition extending as early as the eighteenth century with the Jesuit Louis Bertrand Castel building an ocular harpsichord in the 1730s (visited by Georg Philipp Telemann, who composed for it). Other prominent color organ artist-inventors include: Alexander Wallace Rimington, Bainbridge Bishop, Thomas Wilfred, Charles Dockum, Mary Hallock-Greenewalt and Kurt Laurenz Theinert.[citation needed]

On film[edit]

Visual music and abstract film or video often coincide. Some of the earliest known films of these two genres were hand-painted works produced by the Futurists Bruno Corra[3] and Arnaldo Ginna between 1911 and 1912 (as they report in the Futurist Manifesto of Cinema), which are now lost. Mary Hallock-Greenewalt produced several reels of hand-painted films (although not traditional motion pictures) that are held by the Historical Society of Philadelphia. Like the Futurist films, and many other visual music films, her 'films' were meant to be a visualization of musical form.

Notable visual music filmmakers include: Walter Ruttmann, Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye, Jordan Belson, Norman McLaren, Harry Smith, Hy Hirsh, John, James Whitney, Steven Woloshen, Richard Reeves and many others up to present day.

Computer graphics[edit]

The cathode ray tube made possible the oscilloscope, an early electronic device that can produce images that are easily associated with sounds from microphones. The modern Laser lighting display displays wave patterns produced by similar circuitry. The imagery used to represent audio in digital audio workstations is largely based on familiar oscilloscope patterns.

The Animusic company (originally called 'Visual Music') has repeatedly demonstrated the use of computers to convert music — principally pop-rock based and composed as MIDI events — to animations. Graphic artist-designed virtual instruments which either play themselves or are played by virtual objects are all, along with the sounds, controlled by MIDI instructions.[4]

In the image-to-sound sphere, MetaSynth[5] includes a feature which converts images to sounds. The tool uses drawn or imported bitmap images, which can be manipulated with graphic tools, to generate new sounds or process existing audio. A reverse function allows the creation of images from sounds.[6]

Virtual reality[edit]

With the increasing popularity of head mounted displays for virtual reality [7][8][9] there is an emerging new platform for visual music. While some developers have been focused on the impact of virtual reality on live music [10] or on the possibilities for music videos,[11] virtual reality is also an emerging field for music visualization[12][13][14][15] and visual music.[16]

Graphic notation[edit]

Many composers have applied graphic notation to write compositions. Pioneering examples are the graphical scores of John Cage and Morton Feldman. Also known is the graphical score of György Ligeti's Artikulation designed by Rainer Wehinger, and Sylvano Bussotti.

Musical theorists such as Harry Partch, Erv Wilson, Ivor Darreg, Glenn Branca, and Yuri Landman applied geometry in detailed visual musical diagrams explaining microtonal structures and musical scales.

See also[edit]

Science[edit]

Industry[edit]

- VJing - The art of performing visual music

- Motion graphics - a process or technique often used in contemporary visual music

- Video synthesizer

- Visual album

Similar types of art[edit]

- Abstract film or Experimental film or Video art

- Audiovisual art

- Sound art or Sound sculpture or Sound installation

Notes[edit]

- ^ Ward, Ossian (9 June 2006). "The man who heard his paintbox hiss" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Moritz, W, (1997), The Dream of Color Music, And Machines That Made it Possible in Animation World Magazine

- ^ Bruno Corra at IMDb

- ^ Alberts, Randy (March 22, 2006). "Inside Animusic's Astonishing Computer Music Videos". O'Reilly Media, Inc. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "MetaSynth 5 for Mac OS". www.uisoftware.com.

- ^ Sasso, Len (1 October 2005). "U&I SOFTWARE MetaSynth 4 (Mac)". Electronic Musician. Archived from the original on 1 March 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Tractica: Expect Big Sales of VR Head-Mounted Displays". www.wearabletechworld.com.

- ^ "Global VR headset sales by brand 2016-2017 - Statistic". Statista.

- ^ "How Big Is the Installed Base for Virtual Reality? - Studio Daily". studiodaily.com. 11 January 2017.

- ^ "How virtual reality is redefining live music". nbcnews.com.

- ^ Moylan, Brian (4 August 2016). "Virtual insanity: is VR the new frontier for music videos?". the Guardian.

- ^ Mills, Chris. "VR Music Visualizers Are Like Tripping Without Drugs". gizmodo.com.

- ^ "Does anybody really want a virtual reality music visualizer?". theverge.com.

- ^ "GrooVR Music Driven Virtual Reality - Music Visualizer". groovr.com.

- ^ "PlayStation.Blog". PlayStation.Blog.

- ^ "Inventor updates '70s creation to bring 3-D vision to music - The Boston Globe". bostonglobe.com.

Further reading[edit]

- Kerry Brougher et al. Visual Music: Synesthesia in Art and Music Since 1900. Thames and Hudson, 2005.

- Martin Kemp, The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat. New Haven: Yale, 1992.

- Maarten Franssen, "The Ocular Harpsichord of Louis-Bertrand Castel." Tractrix: Yearbook for the History of Science, Medicine, Technology and Mathematics 3, 1991.

- Maura McDonnell, "Constructing Visual Music Images with Electroacoustic Music Concepts." In Andrew J. Hill, editor, Sound and Image: Aesthetics and Practices. Taylor & Francis Group, 2020.

- Aimee Mollaghan, The Visual Music Film. Palgrave, 2015.

- Keely Orgeman, ed. Lumia. Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light. Yale University Art Gallery, 2017.

- Hermann von Helmholtz, Psychological Optics, Volume 2. [S.l.]: The Optical Society of America, 1924. DjVu, UPenn Psychology site

- William Moritz, "The Dream of Color Music and Machines That Made it Possible." Animation World Magazine (April 1997).

- William Moritz, "Visual Music and Film as an Art before 1950." In Paul J. Karlstrom, editor, On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900-1950. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

- William Moritz, Towards an Aesthetic of Visual Music. ASIFA Canada Bulletin, Vol 14, December 1986.

- Campen, Cretien van. "The Hidden Sense. Synesthesia in Art and Science." Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007.

- Dina Riccò & Maria José de Cordoba (edited by), "MuVi. Video and moving image on synesthesia and visual music", Milan: Edizioni Poli.design, 2007. [Book + DVD]

- Dina Riccò & Maria José de Cordoba (edited by), "MuVi3. Video and moving image on synesthesia and visual music", Ediciones Fundación Internacional Artecittà [Granada, 2012] [Book + DVD]

- Dina Riccò & Maria José de Cordoba (edited by), "MuVi4. Video and moving image on synesthesia and visual music", Granada: Ediciones Fundación Internacional Artecittà, 2015. [Book + DVD]

- Michael Betancourt, "Mary Hallock-Greenewalt's Abstract Films." [Millennium Film Journal no 45, 2006]

- Holly Rogers, Sounding the Gallery: Video and the Rise of Art Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

External links[edit]

Media related to Visual music at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Visual music at Wikimedia Commons