The Sound of Silence

| "The Sound of Silence" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Side-A label of the 1965 U.S. vinyl single | ||||

| Single by Simon & Garfunkel | ||||

| from the album Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. and Sounds of Silence | ||||

| B-side | "We've Got a Groovy Thing Goin'" | |||

| Released | October 19, 1964 (original acoustic version); September 12, 1965 (overdubbed electric version) | |||

| Recorded | March 10, 1964 | |||

| Studio | Columbia 7th Ave, New York City | |||

| Genre | Folk rock[1] | |||

| Length | 3:05 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Paul Simon | |||

| Producer(s) | Tom Wilson | |||

| Simon & Garfunkel singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio | ||||

| "The Sound of Silence" on YouTube | ||||

| Alternative release | ||||

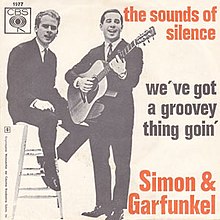

Artwork for the original 1966 German vinyl single | ||||

"The Sound of Silence" (originally "The Sounds of Silence") is a song by the American music-duo Simon & Garfunkel, written by Paul Simon. The duo's studio audition of the song led to a record deal with Columbia Records, and the original acoustic version was recorded in March 1964 at Columbia's 7th Avenue Recording Studios in New York City for their debut album, Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., released that October to disappointing sales.

In 1965, the song began to attract airplay at radio stations in Boston and throughout Florida. The growing airplay led Tom Wilson, the song's producer, to remix the track, overdubbing electric instruments and drums. This remixed version was released as a single in September 1965. Simon & Garfunkel were not informed of the song's remix until after its release. The remix hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for the week ending January 1, 1966, leading the duo to reunite and hastily record their second album, which Columbia titled Sounds of Silence in an attempt to capitalize on the song's success. The remixed single version of the song was included on this follow-up album. Later, it was featured in the 1967 film The Graduate and was included on the film's soundtrack album. It was additionally released on the Mrs. Robinson EP in 1968, along with three other songs from the film: "Mrs. Robinson", "April Come She Will", and "Scarborough Fair/Canticle".

"The Sound of Silence" was a top-ten hit in multiple countries worldwide, among them Australia, Austria, West Germany, Japan and the Netherlands. Generally considered a classic folk rock song, the song was added to the National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically important" in 2012, along with the rest of the Sounds of Silence album. Since its release, the song was included in later compilations, beginning with the 1972 compilation album Simon and Garfunkel's Greatest Hits.[2]

Background[edit]

Origin and original recording[edit]

Simon and Garfunkel had become interested in folk music and the growing counterculture movement separately in the early 1960s. Having performed together previously under the name Tom and Jerry in the late 1950s, their partnership had dissolved by the time they began attending college. In 1963, they regrouped and began performing Simon's original compositions locally in Queens. They billed themselves "Kane & Garr", after old recording pseudonyms, and signed up for Gerde's Folk City, a Greenwich Village club that hosted Monday night performances.[3] In September 1963, the duo's performances caught the attention of Columbia Records producer Tom Wilson, a young African-American jazz musician who was also helping to guide Bob Dylan's transition from folk to rock.[4][3][5] Simon convinced Wilson to let him and his partner have a studio audition; their performance of "The Sound of Silence" got the duo signed to Columbia.[6]

The song's origin and basis are unclear, with some thinking that the song commented on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, as the song was recorded three months after the assassination, although Simon & Garfunkel had performed the song live as Kane & Garr two months before the assassination.[7] Simon wrote "The Sound of Silence" when he was 21 years old,[8][9] later explaining that the song was written in his bathroom, where he turned off the lights to better concentrate.[10] "The main thing about playing the guitar, though, was that I was able to sit by myself and play and dream. And I was always happy doing that. I used to go off in the bathroom, because the bathroom had tiles, so it was a slight echo chamber. I'd turn on the faucet so that water would run (I like that sound, it's very soothing to me) and I'd play. In the dark. 'Hello darkness, my old friend / I've come to talk with you again.'"[11] According to Garfunkel, the song was first developed in November 1963, but Simon took three months to perfect the lyrics, which were entirely written on February 19, 1964.[12] Garfunkel, introducing the song at a live performance (with Simon) in Haarlem (Netherlands), in June 1966, summed up the song's meaning as "the inability of people to communicate with each other, and not particularly internationally but especially emotionally, so that what you see around you is people who are unable to love each other."[10]

Garfunkel's college roommate, Sandy Greenberg, wrote in his memoir that the song reflected the strong bond of friendship between Simon and Garfunkel, who had adopted the epithet "Darkness" to empathise with Greenberg's sudden-onset blindness.[13]

To promote the release of their debut album, Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., released on October 19, 1964,[14] the duo performed again at Folk City, as well as two shows at the Gaslight Café, which went over poorly. Dave Van Ronk, a folk singer, was at the performances, and noted that several in the audience regarded their music as a joke.[15] "'Sounds of Silence' actually became a running joke: for a while there, it was only necessary to start singing 'Hello darkness, my old friend ... ' and everybody would crack up."[16] Wednesday Morning, 3 AM sold only 3,000 copies upon its October release, and its dismal sales led Simon to move to London.[17] While there, he recorded a solo album, The Paul Simon Songbook (1965), which features a rendition of the song, titled "The Sound of Silence" (instead of "The Sounds of Silence", as on Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.).[18]

The original recording of the song is in D♯ minor, using the chords D♯m, C♯, B and F♯. Simon plays a guitar with a capo on the sixth fret, using the shapes for Am, G, F and C chords. He provides the lower vocals for harmony while Garfunkel sings the melody.[19] The vocal span goes from C♯3 to F♯4 in the song.[20]

Remix[edit]

Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. had been a commercial failure before producer Tom Wilson was alerted that radio stations had begun to play "The Sound of Silence" in spring 1965. A late-night disc jockey at WBZ in Boston began to spin "The Sound of Silence", where it found a college student audience.[21] Those at Harvard and Tufts University responded well, and the song made its way down the east coast pretty much "overnight", "all the way to Cocoa Beach, Florida, where it caught the students coming down for spring break."[21] A promotional executive for Columbia went to give away free albums of new artists, and beach-goers were interested only in the artists behind "The Sound of Silence". He phoned the home office in New York, alerting them of its appeal.[22] An alternate version of the story states that Wilson attended Columbia's July 1965 convention in Miami, where the head of the local sales branch raved about the song's airplay.[23]

Folk rock was beginning to make waves on pop radio, with songs such as the Byrds' "Mr. Tambourine Man" charting high.[24] Wilson listened to the song several times, thinking it too soft for a wide release.[21] He had strong feelings about editing the song with explicit rock overtones.[25] As stated by Geoffrey Himes, "If Columbia Records producer Tom Wilson hadn't taken the initiative, without the singers' knowledge, to dub a rock rhythm section over their folk rendition, the song never would have become a cultural touchstone—a generation's shorthand for alienation."[26] Wilson had also experimented the previous December with overdubbing an electric band over acoustic tracks by Bob Dylan; these recordings were never officially released, as Dylan and Wilson opted to record new tracks with a live band for what would become the album Bringing It All Back Home.

On June 15, 1965, following sessions for Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone", Wilson retained guitarist Al Gorgoni and drummer Bobby Gregg from the Dylan sessions, adding guitarist Vinnie Bell and bassist Bob Bushnell.[27] The tempo on the original recording was uneven, making it difficult for the musicians to keep the song in time.[24] Engineer Roy Halee employed a heavy echo on the remix, which was a common trait of the Byrds' hits.[24] The single was first provided to college FM rock stations, and a commercial single release followed on September 13, 1965.[23] The lack of consultation with Simon and Garfunkel on the remix was because, although the duo was still contracted to Columbia Records, the duo was no longer a "working entity".[24][28] It was not unusual for producers to add instruments or vocals to previous releases and re-release them as new products.[citation needed]

In the fall of 1965, Simon was in Denmark, performing at small clubs, and picked up a copy of Billboard, as he had routinely done for several years.[23] Upon seeing "The Sound of Silence" in the Billboard Hot 100, he bought a copy of Cashbox and saw the same thing. Several days later, Garfunkel excitedly called Simon to inform him of the single's growing success.[23] A copy of the 7-inch single arrived in the mail the next day, and according to friend Al Stewart, "Paul was horrified when he first heard it ... [when the] rhythm section slowed down at one point so that Paul and Artie's voices could catch up."[25] Garfunkel was far less concerned about the remix, feeling conditioned to the process of trying to create a hit single: "It's interesting, I suppose it might do something, It might sell," he told Wilson.[29]

Lyrics[edit]

The lyrics of the song are written in five stanzas of seven lines each. Each stanza begins with a couplet describing the setting of the scene, followed by a couplet driving the action forward and another couplet expressing the climactic thought of the verse, and closes with a one-line refrain referring to "the sound of silence". This structure is supported by a melodic contour, where the first and second lines are paired with the arpeggio A-C-E-D and a repeat a step lower, respectively. The arpeggio is then stretched to become C-E-G-A-G and repeated twice in the second couplet. For the last three lines, the contour then leaps from C to the higher A, rises to the higher C, and then falls back to the A before singing the stretched arpeggio in reverse and finally retreating to the lower A.[19] The progress of the lyrics through its five stanzas places the singer into an incrementally increasing tension with an increasingly ambiguous "sound of silence". The irony of using the word "sound" to describe silence in the title lyrics suggests a paradoxical symbolism being used by the singer, which the lyrics of the fourth stanza eventually identifies as "silence like a cancer grows". The "sound of silence" is symbolically taken also to denote the cultural alienation associated with much of the 1960s.[26] In the counterculture movements of the 1960s, the phrase "sound of silence" can be compared to other more commonly used turns of phrase such as "turning a deaf ear" often associated with the detachment experienced with impersonal large governments.[by whom?]

The first stanza presents the singer as taking some relative solace in the peacefulness he associates with "darkness" which is submerged "within" the ambiguous sound of silence.[30] The second stanza has the effect of breaking into the silence with "the flash of a neon light" which leaves the singer "touched" by the enduring ambiguity of the sound of silence. In the third stanza, a "naked light" emerges as a vision of 10,000 people all caught within their own solitude and alienation without any one of them daring to "disturb" the recurring sound of silence.

In the fourth stanza, the singer proclaims in a declarative voice that "silence like a cancer grows," though his words "like silent raindrops fell" without ever being heard against the by now cancerous sound of silence. The fifth stanza appears to culminate with the urgency raised by the declarative voice in the fourth stanza through the apparent triumph of a false "neon god". The false neon god is only challenged when a "sign flashed out its warning" that only the words of the indigent written on "subway walls and tenement halls" could still "whisper" their truth against the recurring and ambiguous form of "the sound of silence".[5] The song has no lyrical bridge or change of key, and was written without any lyrical intro or outro.

Personnel[edit]

- Paul Simon – acoustic guitar, vocals

- Art Garfunkel – vocals

- Barry Kornfeld – acoustic guitar

- Bill Lee – double bass

(electric overdubs) personnel

- Al Gorgoni, Vinnie Bell – guitar

- Joe Mack (also known as Joe Macho) – bass guitar

- Bobby Gregg – drums

Charts performance[edit]

Charts history[edit]

"The Sound of Silence" first broke in Boston, where it became one of the top-selling singles in early November 1965;[23][31] it spread to Miami and Washington, D.C. two weeks later, reaching number one in Boston and debuting on the Billboard Hot 100.[32]

Throughout the month of January 1966 "The Sound of Silence" had a one-on-one battle with the Beatles' "We Can Work It Out" for the number one spot on the Billboard Hot 100. "The Sound of Silence" was number one for the weeks of January 1 and 22 and number two for the intervening two weeks. "We Can Work It Out" held the top spot for the weeks of January 8, 15, and 29, and it was number two for the two weeks that "The Sound of Silence" was number one. Overall, "The Sound of Silence" spent 14 weeks on the Billboard chart.[33]

In the wake of the song's success, Simon promptly returned to the United States to record a new Simon & Garfunkel album at Columbia's request. He later described his experiences learning the song went to number one, a story he repeated in numerous interviews:[34]

I had come back to New York, and I was staying in my old room at my parents' house. Artie was living at his parents' house, too. I remember Artie and I were sitting there in my car one night, parked on a street in Queens, and the announcer [on the radio] said, "Number one, Simon & Garfunkel." And Artie said to me, "That Simon & Garfunkel, they must be having a great time." Because there we were on a street corner [in my car in] Queens, smoking a joint. We didn't know what to do with ourselves.[35]

For his part, Garfunkel had a different memory of the song's success:

We were in L.A. Our manager called us at the hotel we were staying at. We were both in the same room. We must have bunked in the same room in those days. I picked up the phone. He said, 'Well, congratulations. Next week you will go from five to one in Billboard.' It was fun. I remember pulling open the curtains and letting the brilliant sun come into this very red room, and then ordering room service. That was good.[34][36]

A cover by Peaches & Herb reached #88 in Canada, July 24, 1971.[37]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications[edit]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[59] | Gold | 75,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[60] | Gold | 45,000‡ |

| Germany (BVMI)[61] | Gold | 250,000‡ |

| Italy (FIMI)[62] | Platinum | 50,000‡ |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[63] | Platinum | 60,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[64] | Platinum | 600,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[65] | Gold | 1,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Cover by The Bachelors[edit]

The cover by the Irish group The Bachelors was released in 1966. Simon and Garfunkel's version did not chart in either the UK or Ireland, losing out to The Bachelors cover version, whose version peaked at number three in the UK and number nine in Ireland.

Chart performance[edit]

|

|

Cover by Disturbed[edit]

| "The Sound of Silence" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Disturbed | ||||

| from the album Immortalized | ||||

| Released | December 7, 2015 | |||

| Recorded | 2015 | |||

| Studio | The Hideout Recording Studio Las Vegas, Nevada | |||

| Genre | Symphonic rock | |||

| Length | 4:08 | |||

| Label | Reprise | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Paul Simon | |||

| Producer(s) | Kevin Churko | |||

| Disturbed singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "The Sound of Silence" on YouTube | ||||

50 years after its original release, a cover version of "The Sound of Silence" was released by American heavy metal band Disturbed on December 7, 2015.[68][69] A music video was also released.[70] Their cover hit number one on the Billboard Hard Rock Digital Songs[71] and Mainstream Rock charts,[72] and is their highest-charting song on the Hot 100,[73] peaking at number 42. It is also their highest-charting single in Australia, peaking at number four. David Draiman sings it in the key of F#m. His vocal span goes from F#2 to A4 in scientific pitch notation.[74]

In April 2016, Paul Simon endorsed the cover.[75] Additionally, on April 1, Simon sent Draiman an email praising Disturbed's performance of the rendition on American talk show Conan. Simon wrote, "Really powerful performance on Conan the other day. First time I'd seen you do it live. Nice. Thanks." Draiman responded, "Mr. Simon, I am honored beyond words. We only hoped to pay homage and honor to the brilliance of one of the greatest songwriters of all time. Your compliment means the world to me/us and we are eternally grateful."[76] As of September 2017, the single had sold over 1.5 million digital downloads[77] and had been streamed over 54 million times, estimated Nielsen Music.[78] As of March 2024, the music video has over 976 million views on YouTube, while the live performance on Conan has over 144 million, making it the most watched YouTube video from the show.[79][80]

In 2024, a remix by Australian DJ Cyril was released on Spinnin Records

Accolades[edit]

| Region | Year | Publication | Accolade | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 2015 | Loudwire | 20 Best Rock Songs of 2016[81] | 1 |

| 10 Best Rock Videos of 2016[82] | 2 |

Weekly charts[edit]

Monthly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

Decade-end charts[edit]

Certifications[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paul Simon solo versions[edit]

| "The Sound of Silence" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single by Paul Simon | ||||

| from the album Paul Simon in Concert: Live Rhymin' | ||||

| Released | 1974 | |||

| Genre | Folk rock | |||

| Length | 4:21 | |||

| Label | Columbia Records | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Paul Simon | |||

| Producer(s) | Paul Simon | |||

| Paul Simon singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Paul Simon released a solo acoustic version of "The Sound of Silence" in the spring of 1974. His version reached No. 84 in Canada[52] and No. 97 on the US Cash Box chart.[48] It was also a minor Adult Contemporary hit (US No. 50, Canada No. 42).[53][51]

Simon had previously recorded a solo acoustic version of the song on his debut solo album The Paul Simon Songbook, released in 1965 in the UK only, and not widely available in the U.S. until its release as part of a retrospective box set in the 1980s.

Legacy[edit]

In 1999, BMI named "The Sound of Silence" as the 18th most-performed song of the 20th century.[139] In 2004, it was ranked No. 156 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, one of the duo's three songs on the list. The song is now considered "the quintessential folk rock release".[140] On March 21, 2013, the song was added to the National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress for long-term preservation along with the rest of the Sounds of Silence album.[141]

In 2004, the song was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.[142]

In popular culture[edit]

Film and television[edit]

When director Mike Nichols and Sam O'Steen were editing the 1967 film The Graduate, they initially timed some scenes to this song, intending to substitute original music for the scenes. However, they eventually concluded that an adequate substitute could not be found and decided to purchase the rights for the song for the soundtrack. This was an unusual decision, as the song had charted more than a year earlier, and recycling established music for film was not commonly done at the time.[143]

It was featured in the 2009 dystopian-Superhero film Watchmen, directed by Zack Snyder.[citation needed]

A shortened cover of the song, performed by Anna Kendrick, was featured in the 2016 film Trolls. It was also included on the film’s soundtrack album, Trolls: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack.[144] It was also the b-side to the film’s lead single, the Oscar-nominated original song "Can't Stop the Feeling!" by Justin Timberlake, which was released on May 6, 2016.[145]

Other allusions and parodies[edit]

The Canadian band Rush alluded to the song lyrics in the last lines of their 1980 song "The Spirit of Radio".[146]

The 1994 fifth season episode of The Simpsons "Lady Bouvier's Lover" has a parody of the song called "The Sound of Grampa" over a scene that parodies the end of the 1967 movie The Graduate.[147]

In 2017, the song re-emerged on Billboard's Hot Rock Songs Chart at no. 6, due to its use in a YouTube video and meme involving Ben Affleck's facial expression during an interview about his film Batman v Superman, dubbed "Sad Affleck."[148]

In January 2020, American rapper Eminem released the song "Darkness", which interpolates "The Sound of Silence" and uses its opening line, "Hello, darkness, my old friend."[149]

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ Kruth, John (2015). This Bird Has Flown: The Enduring Beauty of Rubber Soul, Fifty Years On. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-61713-573-6.

- ^ Mastropolo, Frank (March 10, 2015). "51 Years Ago: Simon & Garfunkel Record Their First Classic, 'The Sounds of Silence'". Ultimate Classic Rock.

- ^ a b Eliot 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Michael Hall (January 6, 2014). "The Greatest Music Producer You've Never Heard of Is..." Texas Monthly. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Eliot 2010, p. 40.

- ^ Eliot 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Marc Eliot (October 2010). Paul Simon: A Life. John Wiley and Sons. p. 39. ISBN 9780470433638.

- ^ "Paul Simon - Interview - 7/6/1986 (Official)". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Paul Simon chats about his youth. YouTube. April 19, 2011. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Marc Eliot (October 2010). Paul Simon: A Life. John Wiley and Sons. p. 40. ISBN 9780470433638.

- ^ Schwartz, Tony (February 1984). "Playboy Interview" (PDF). Playboy. 31 (2): 49–51, 162–176.

- ^ Fornatale 2007, p. 38.

- ^ "Art Garfunkel's Beloved Blind College Roommate Awards $3 Million to Scientists to Cure Blindness". People.com. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Original versions of The Sound of Silence by The Bachelors [IE]". SecondHandSongs.

- ^ Eliot 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Eliot 2010, p. 48.

- ^ Eliot 2010, p. 53.

- ^ Eliot 2010, p. 58.

- ^ a b Bennighof, James (2007). The Words and Music of Paul Simon. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-275-99163-0. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ "Simon & Garfunkel "The Sound of Silence" Sheet Music in D Minor (transposable)". Musicnotes.com. September 14, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c Eliot 2010, p. 64.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (August 1, 2012). "Interview: Art Garfunkel on his new greatest hits CD, The Singer". MusicRadar.

- ^ a b c d e Sullivan, Steve (2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings, Volume 2. pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c d Simons, David. Studio Stories. pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b Eliot 2010, p. 65.

- ^ a b Geoffrey Himes. "How “The Sound of Silence” Became a Surprise Hit." Smithsonian Magazine. Jan-Feb 2016..

- ^ Charlesworth, Chris (1996). "Sound of Silence". The Complete Guide to the Music of Paul Simon and Simon & Garfunkel. Omnibus Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9780711955974.

- ^ Simons, David (2004). Studio Stories: How the Great New York Records Were Made. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. pp. 94–97. ISBN 9781617745164.

- ^ Fornatale 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Schwartz, Tony (February 1984). "Playboy Interview" (PDF). Playboy. 31 (2): 49–51, 162–176.

- ^ "Top Sellers in Top Markets". Billboard. Vol. 77, no. 45. November 6, 1965. p. 14. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ^ "Top Sellers in Top Markets". Billboard. Vol. 77, no. 47. November 20, 1965. pp. 14–15. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ^ Billboard Charts Archives for 1965 and 1966

- ^ a b Fornatale 2007, p. 47.

- ^ Eliot 2010, p. 66.

- ^ Fornatale 2007, p. 48.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Singles - July 24, 1971" (PDF).

- ^ "The Sounds of Silence". Ultratop. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Canada, Library and Archives (July 17, 2013). "Image : RPM Weekly". Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "サイモン&ガーファンクルのシングル売上TOP8作品". Oricon. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023.

サウンド・オブ・サイレンス - 発売日 - 1968年06月15日 - 最高順位 - 1位 - 登場回数 - 59週

- ^ オリジナルコンフィデンス. 歴代洋楽シングル売り上げ枚数ランキング (in Japanese). 年代流行. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ "NZ Listener Chart - Simon and Garfunkel". www.flavourofnz.co.nz. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ "SA Charts 1965–March 1989". Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "Simon & Garfunkel: The Sounds of Silence". swisscharts.com. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ "Billboard Hot 100 - Simon & Garfunkel". Billboard Magazine. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023.

- ^ Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955-1990 - ISBN 0-89820-089-X

- ^ a b "Cash Box Top 100 1/29/66". Tropicalglen.com. January 29, 1966. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ * Zimbabwe. Kimberley, C. Zimbabwe: singles chart book. Harare: C. Kimberley, 2000

- ^ "Simon & Garfunkel Chart History (Hot Rock & Alternative Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Item Display - RPM - Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. June 8, 1974. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Item Display - RPM - Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. May 25, 1974. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel (1993). Top Adult Contemporary: 1961-1993. Record Research. p. 216.

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 5/18/74". Cashboxmagazine.com. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Top 20 Hit Singles of 1966". Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Hits of 1966/Top 100 Songs of 1966". Musicoutfitters.com. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Cash Box Year-End Charts: 1966/Top 100 Pop Singles, December 24, 1966". Tropicalglen.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Hot Rock Songs – Year-End 2016". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Canadian single certifications – Simon And Garfunkel – The Sound of Silence". Music Canada. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ "Danish single certifications – Simon & Garfunkel – The Sound of Silence". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Simon & Garfunkel; 'The Sound of Silence')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – Simon & Garfunkel – The Sound of Silence" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved February 22, 2021. Select "2016" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Select "The Sound of Silence" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Singoli" under "Sezione".

- ^ certweek IS REQUIRED for SPANISH CERTIFICATION.

- ^ "British single certifications – Simon & Garfunkel – The Sound of Silence". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ "American single certifications – Simon & Garfunkel – Sounds of Silence". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – The Sound of Silence". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "The Bachelors: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company.

- ^ "Disturbed Return with 'Immortalized' - Billboard". Billboard. June 23, 2015.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum - RIAA". RIAA. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Video Premiere: Disturbed's Cover Version Of Simon & Garfunkel's 'The Sound Of Silence'". Blabbermouth. December 7, 2015.

- ^ "Hard Rock Digital Songs, Jan 2, 2016". Billboard. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ "The Sound of Silence-d Guitars: Disturbed's Haunting Simon & Garfunkel Cover Tops Mainstream Rock Songs Chart". Billboard. March 10, 2016.

- ^ "Simon & Garfunkel's 'Sound of Silence' Hits Hot Rock Songs Top 10, Thanks to 'Sad Affleck'". Billboard. April 6, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed "The Sound of Silence" Sheet Music in F# Minor (transposable) - Download & Print - SKU: MN0164135". Musicnotes.com. May 24, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Paul Simon Endorses Disturbed's 'Sound of Silence' Cover on Facebook". Facebook.com. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "Disturbed Receive Paul Simon Approval for 'Sound of Silence'". Loudwire.com. April 3, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Nielsen SoundScan charts – Digital Songs – Week Ending: 09/28/2017" (PDF). Nielsen SoundScan. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Ayers, Mike (May 25, 2016). "With 'The Sound of Silence,' Disturbed Finds a Crossover Moment - Speakeasy - WSJ". Blogs.wsj.com. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Disturbed - The Sound Of Silence (Official Music Video) [4K UPGRADE], retrieved March 1, 2024

- ^ Disturbed "The Sound Of Silence" 03/28/16 | CONAN on TBS, retrieved March 1, 2024

- ^ "20 Best Rock Songs of 2016". Loudwire.

- ^ "10 Best Rock Videos of 2016". Loudwire.

- ^ "Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". ARIA Top 50 Singles. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed – The Sound of Silence" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed – The Sound of Silence" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed Chart History (Canadian Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "ČNS IFPI" (in Czech). Hitparáda – Radio Top 100 Oficiální. IFPI Czech Republic. Note: Change the chart to CZ – RADIO – TOP 100 and insert 201650 into search. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "ČNS IFPI" (in Czech). Hitparáda – Digital Top 100 Oficiální. IFPI Czech Republic. Note: Change the chart to CZ – SINGLES DIGITAL – TOP 100 and insert 202414 into search. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ "Disturbed: The Sound Of Silence" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ "Top Singles (Week 15, 2024)" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ "Disturbed – The Sound of Silence" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ "Airplay Charts Deutschland – Woche 01/2017". German Charts. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Archívum – Slágerlisták – MAHASZ" (in Hungarian). Dance Top 40 lista. Magyar Hanglemezkiadók Szövetsége. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ "Archívum – Slágerlisták – MAHASZ" (in Hungarian). Single (track) Top 40 lista. Magyar Hanglemezkiadók Szövetsége. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ "Chart Track: Week 19, 2016". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ {{cite web|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240310132725/http://www.hitradio.ma/top30%7Ctitle=TOP30%7Cpublisher=hitradio.ma%7Caccess-date=12 March 2024

- ^ "NZ Top 40 Singles Chart". Recorded Music NZ. May 30, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ "OLiS – oficjalna lista airplay" (Select week 06.04.2024–12.04.2024.) (in Polish). OLiS. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com - Singles (Week 22)". Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Portugal Digital Songs". Billboard. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ "Russia Airplay Chart for 2024-03-15." TopHit. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ "ČNS IFPI" (in Slovak). Hitparáda – Singles Digital Top 100 Oficiálna. IFPI Czech Republic. Note: Select SINGLES DIGITAL - TOP 100 and insert 202412 into search. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "SloTop50 – Slovenian official singles chart". slotop50.si. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ "Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". Singles Top 100. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ "Official Rock & Metal Singles Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine Airplay Chart for 2024-03-22." TopHit. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ "Disturbed Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed Chart History (Hot Rock & Alternative Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed Chart History (Rock Airplay)". Billboard. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ^ "Disturbed Chart History (Global 200)". Billboard. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ "Disturbed Chart History (Luxembourg Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ "OLiS – oficjalna lista sprzedaży – single w streamie" (Select week 29.03.2024–04.04.2024.) (in Polish). OLiS. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ "Russia Airplay Chart for 2024-03-29." TopHit. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Russia Monthly Chart: March 2024". TopHit. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Singles 2016". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ "Ö3 Austria Top 40 - Single-Charts 2016". oe3.orf.at. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ "Top 100 Jahrescharts 2016". GfK Entertainment (in German). viva.tv. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ "Årslista Singlar – År 2016" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ "Rock Songs – Year-End 2016". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "Rock Airplay Songs – Year-End 2016". Billboard. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Bald ist nicht nur das Jahr zu Ende, sondern auch das ganze Jahrzehnt. Deshalb präsentieren wir euch ab heute die 50 erfolgreichsten Singles und Alben der Zehnerjahre. Platz 50 der Singles geht an Disturbed, Platz 50 der Alben an Tim @bendzko ("Wenn Worte meine Sprache wären")". GfK Entertainment (in German). offiziellecharts.de. Retrieved November 18, 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Decade-End Charts: Hot Rock Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2016 Singles" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ "Austrian single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence" (in German). IFPI Austria.

- ^ "Canadian single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". Music Canada. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "Danish single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Disturbed; 'The Sound of Silence')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "New Zealand single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ "Norwegian single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia – Platynowe płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 2022 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ "Sverigetopplistan – Disturbed" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('The Sound of Silence')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- ^ "British single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ "American single certifications – Disturbed – The Sound of Silence". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "BMI Top 100 Songs of the Century: 8 Million+ Performances". Archived from the original on July 12, 2001. Retrieved April 20, 2017., 1999 (archive.org copy)

- ^ Hoffmann, Frank (2005). "Folk Rock". Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 0-415-93835-X.

- ^ "Simon & Garfunkel song among those to be preserved". CFN13. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ https://www.grammy.com/awards/hall-of-fame-award#s

- ^ Harris, Mark (2008). Pictures at a Revolution. Penguin. pp. 360–1. ISBN 9781594201523.

- ^ "Various - TROLLS (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". Amazon.com. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Platon, Adelle (May 6, 2016). "Justin Timberlake Delivers Delightful Single 'Can't Stop The Feeling': Watch". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "The Story Behind The Song: The Spirit Of Radio by Rush". Classic Rock Magazine. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Groening, Matt (2007). The Trivial Simpsons 2008 366-Day Calendar. Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-123130-8.

- ^ Loughrey, Clarisse (April 7, 2016). "Simon & Garfunkel's Sound of Silence climbs rock charts thanks to 'Sad Ben Affleck' meme". The Independent. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Eddie, Fu (January 17, 2020). "Eminem Channels The Perspective Of The 2017 Las Vegas Shooter On "Darkness"". Genius. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

Bibliography

- Eliot, Marc (2010). Paul Simon: A Life. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-43363-8.

- Fornatale, Pete (2007). Simon and Garfunkel's Bookends. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-427-8.

External links[edit]

- 1965 songs

- 1965 singles

- 1960s ballads

- 1974 singles

- 2016 singles

- Songs written by Paul Simon

- Simon & Garfunkel songs

- Mercy (band) songs

- Disturbed (band) songs

- Anna Kendrick songs

- The Bachelors songs

- Song recordings produced by Tom Wilson (record producer)

- Billboard Hot 100 number-one singles

- Cashbox number-one singles

- Number-one singles in Austria

- Number-one singles in South Africa

- Oricon Weekly number-one singles

- CBS Records singles

- Columbia Records singles

- Reprise Records singles

- Folk ballads

- Rock ballads

- Silence

- Black-and-white music videos

- United States National Recording Registry recordings