The Love for Three Oranges (fairy tale)

| The Love for Three Oranges | |

|---|---|

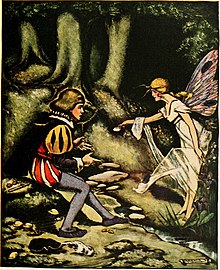

The prince releases the fairy woman from the fruit. Illustration by Edward G. McCandlish for Édouard René de Laboulaye's Fairy Book (1920). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Love for Three Oranges |

| Also known as | The Three Citrons |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 408 (The Three Oranges) |

| Region | Italy |

| Published in | Pentamerone, by Giambattista Basile |

| Related | |

"The Love for the Three Oranges" or "The Three Citrons" (Neapolitan: Le Tre Cetre) is an Italian literary fairy tale written by Giambattista Basile in the Pentamerone.[1] It is the concluding tale, and the one the heroine of the frame story uses to reveal that an imposter has taken her place.

The literary tale by Basile is considered to be the oldest attestation of tale type ATU 408, "The Three Oranges", of the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index. However, variants are recorded from oral tradition among European Mediterranean countries, in the Middle East and Turkey, as well as across Iran and India.[2]

Summary[edit]

A king, who only had one son, anxiously waited for him to marry. One day, the prince cut his finger; his blood fell on white cheese. The prince declared that he would only marry a woman as white as the cheese and as red as the blood, so he set out to find her.

The prince wandered the lands until he came to the Island of Ogresses, where two little old women each told him that he could find what he sought here, if he went on, and the third gave him three citrons, with a warning not to cut them until he came to a fountain. A fairy would fly out of each, and he had to give her water at once.

He returned home, and by the fountain, he was not quick enough for the first two, but was for the third. The woman was red and white, and the prince wanted to fetch her home properly, with suitable clothing and servants. He had her hide in a tree. A black slave, coming to fetch water, saw her reflection in the water, and thought it was her own and that she was too pretty to fetch water. She refused, and her mistress beat her until she fled. The fairy laughed at her in the garden, and the slave noticed her. She asked her story and on hearing it, offered to arrange her hair for the prince. When the fairy agreed, she stuck a pin into her head, and the fairy only escaped by turning into a bird. When the prince returned, the slave claimed that wicked magic had transformed her.

The prince and his parents prepared for the wedding. The bird flew to the kitchen and asked after the cooking. The lady ordered it be cooked, and it was caught and cooked, but the cook threw the water it had been scalded in, into the garden, where a citron tree grew in three days. The prince saw the citrons, took them to his room, and dealt with them as the last three, getting back his bride. She told him what had happened. He brought her to a feast and demanded of everyone what should be done to anyone who would harm her. Various people said various things; the slave said she should be burned, and so the prince had the slave burned.

Analysis[edit]

Tale type[edit]

The tale is classified in the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as tale type ATU 408, "The Three Oranges", and is the oldest known variant of this tale.[3][4][5] Scholarship point that the Italian version is the original appearance of the tale, with later variants appearing in French, such as the one by Le Chevalier de Mailly (Incarnat, blanc et noir (fr)).[6]

In an article in Enzyklopädie des Märchens, scholar Christine Shojaei Kawan separated the tale type into six sections, and stated that parts 3 to 5 represented the "core" of the story:[7]

- (1) A prince is cursed by an old woman to seek the fruit princess;

- (2) The prince finds helpers that guide him to the princess's location;

- (3) The prince finds the fruits (usually three), releases the maidens inside, but only the third survives;

- (4) The prince leaves the princess up a tree near a spring or stream, and a slave or servant sees the princess's reflection in the water;

- (5) The slave or servant replaces the princess (transformation sequence);

- (6) The fruit princess and the prince reunite, and the false bride is punished.

Motifs[edit]

The maiden's appearance[edit]

According to the tale description in the international index, the maiden may appear out of the titular citrus fruits, like oranges and lemons. However, she may also come out of pomegranates or other species of fruits, and even eggs.[8][9]

In de Mailly's version, the fruits the girls are trapped in are apples.[10][11][12]

While analysing the imagery of the golden apples in Balkanic fairy tales, researcher Milena Benovska-Sabkova took notice that the fairy maiden springs out of golden apples in these variants, fruits that are interpreted as having generative properties.[13]

According to Walter Anderson's unpublished manuscript, variants with eggs instead of fruits appear in Southeastern Europe.[14]

The water motif[edit]

In an article discussing the Maltese variants of the tale type, Maltese linguist George Mifsud Chircop drew attention to the water motif and its symbolism: the parents of the prince build a fountain for the people; when the maiden is released from the fruit she asks for food and water; the false bride mistakes the fruit maiden's visage for her own reflection in the water; the maiden is thrown in the water (well) and becomes a fish.[15] Folklorist Christine Goldberg also noted that water motif present in the tale type: the fountain built at the beginning of the story; the release of the fruit maiden near a body of water, and the prince leaving the maiden on a tree near a water source (well or stream). She also remarked that the fountain motif is "echoed" by the well.[16]

The transformations and the false bride[edit]

The tale type is characterized by the substitution of the fairy wife for a false bride. The usual occurrence is when the false bride (a witch or a slave) sticks a magical pin into the maiden's head or hair and she becomes a dove.[a] In some tales, the fruit maiden regains her human form and must bribe the false bride for three nights with her beloved.[18]

In other variants, the maiden goes through a series of transformations after her liberation from the fruit and regains a physical body.[b] In that regard, according to Christine Shojaei-Kawan's article, Christine Goldberg divided the tale type into two forms. In the first subtype, indexed as AaTh 408A, the fruit maiden suffers the cycle of metamorphosis (fish-tree-human) - a motif Goldberg locates "from the Middle East to Italy and France".[20] In the second subtype, AaTh 408B, the girl is transformed into a dove by the needle.[21]

Separated from her husband, she goes to the palace (alone or with other maidens) to tell tales to the king. She shares her story with the audience and is recognized by him.[22]

Parallels[edit]

The series of transformations attested in these variants (from animal to tree to tree splinter or back into the fruit whence she came originally) has been compared to a similar motif in the Ancient Egyptian story of The Tale of Two Brothers.[23]

This cycle of transformations also appears in Iranian tales, specially "The Girl of Naranj and Toranj". Based on the Iranian tales, Iranian scholarship suggests that these traits seem to recall an Iranian deity of vegetation.[24][25][26]

Variants[edit]

Origins[edit]

Scholar Linda Dégh suggested a common origin for tale types ATU 403 ("The Black and the White Bride"), ATU 408 ("The Three Oranges"), ATU 425 ("The Search for the Lost Husband"), ATU 706 ("The Maiden Without Hands") and ATU 707 ("The Three Golden Sons"), since "their variants cross each other constantly and because their blendings are more common than their keeping to their separate type outlines" and even influence each other.[27][c][d]

European origin[edit]

According to Christina Mazzoni, the geographic distribution of the citrus fruit (or citron) in warm weather, its association with the tale type, and the popularity of the story across the European Mediterranean and the Middle East "led to the assumption" of its possible origin in Southern Europe.[31]

Scholar Jack Zipes suggests that the story "may have originated" in Italy, with later diffusion to the rest of Southern Europe and into the Orient.[32] Similarly, Stith Thompson tentatively concluded on an Italian origin, based on the distribution of the variants[33] - a position also favoured by Italo Calvino.[34]

Eastern origin[edit]

Richard McGillivray Dawkins, on the notes on his book on Modern Greek Folktales in Asia Minor, suggested a Levantine origin for the tale, since even Portuguese variants retain an Eastern flavor.[35]

According to his unpublished manuscript on the tale type, Walter Anderson concluded that the tale originated in Persia.[36] The tale type then migrated through two different routes: one to the East, to India, and another to the West, to the Middle East and to the Mediterranean.[37]

Scholar Christine Goldberg, in her monograph, concluded that the tale type emerged as an amalgamation of motifs from other types, integrated into a cohesive whole.[38][39] In another article, she suggested an East to West direction for the diffusion of the tale.[40]

Distribution[edit]

19th century Portuguese folklorist Consiglieri Pedroso stated that the tale was "familiar to the South of Europe".[41] In the same vein, German philologist Bernhard Schmidt located variants in Wallachia, Hungary, Italy and Sicily.[42]

In the 20th century, folklorist Stith Thompson suggested the tale had a regular occurrence in the Mediterranean Area, distributed along Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal.[43] French folklorist Paul Delarue, in turn, asserted that the highest number of variants are to be found in Turkey, Greece, Italy and Spain.[44]

Italian scholars complement their analyses: philologist Gianfranco D'Aronco noted its "large diffusion" in Italy, as well as across the Mediterranean Basin.[45] Other scholars recognize that it is a "very popular tale", but it appears "almost exclusively" in Southern and Southeastern Europe.[46] In addition, Milena Benovska-Sabkova and Walter Puchner state its wide diffusion in the Balkans.[47][48]

Further scholarly research points that variants exist in Austrian, Ukrainian and Japanese traditions.[49] In fact, according to Spanish scholar Carme Oriol, the tale type is "well known" in Asia,[50] even in China and Korea.[51]

The tale type is also found in Africa and in America.[52]

Europe[edit]

Italy[edit]

The "Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi" ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage") promoted research and registration throughout the Italian territory between the years 1968–1969 and 1972. In 1975 the Institute published a catalog edited by Alberto Maria Cirese and Liliana Serafini reported 58 variants of type 408 across Italian sources, under the name Le Tre Melarance.[53] In fact, this country holds the highest number of variants, according to scholarship.[54]

Italo Calvino included a variant The Love of the Three Pomegranates, an Abruzzese version known too as As White as Milk, As Red as Blood but noted that he could have selected from forty different Italian versions, with a wide array of fruit.[55] For instance, the version The Three Lemons, published in The Golden Rod Fairy Book[56] and Vom reichen Grafensohne ("The Rich Count's Son"), where the fruits are Pomeranzen (bitter oranges).[57]

In a Sicilian variant, collected by Laura Gonzenbach, Die Schöne mit den sieben Schleiern ("The Beauty with Seven Veils"), a prince is cursed by an ogress to search high and low for "the beauty with seven veils", and not rest until he finds her. The prince meets three hermits, who point him to a garden protected by lions and a giant, In this garden, there lies three coffers, each one holding a veiled maiden inside. The prince releases the maiden, but leaves her by a tree and returns to his castle. He kisses his mother and forgets his bride. One year later, he remembers the veiled maiden and goes back to her. When he sights her, he finds "an ugly woman". The maiden was transformed into a dove.[58] Laura Gonzenbach also commented that the tale differs from the usual variants, wherein the maiden appears out of a fruit, like an orange, a citron or an apple.[59]

Spain[edit]

North American folklorist Ralph Steele Boggs (de) stated that the tale type was very popular in Spain, being found in Andalusia, Asturias, Extremadura, New and Old Castile.[60]

According to Spanish folklorist Julio Camarena (es), the tale type, also known as La negra y la paloma ("The Black Woman and the Dove"), was one of the "more common" (más usuales) types found in the Province of Ciudad Real.[61]

Portugal[edit]

According to the Portuguese Folktale Catalogue by scholars Isabel Cárdigos and Paulo Jorge Correia, tale type 408 is reported in Portugal with the title As Três Cidras do Amor ("The Three Citrons of Love"), wherein the maidens appear out of citrons and, alternatively, from oranges, lemons, eggs and nuts.[62][63]

Northern Europe[edit]

Author Klara Stroebe published a Northern European variant, from Norway.[64] According to Reidar Thoralf Christiansen, the tale was an "importation", whose source was a hawkerwoman from Kristiania.[65] The tale is listed as the single attestation of tale type 408, Tre sitroner ("The Three Oranges"), according to Ørnulf Hodne's The Types of the Norwegian Folktale. In the singular tale, the heroine is a naked princess transformed into a lemon, and when the false bride replaces her, she undergoes a transformation into a silver fish and a linden tree.[66]

According to the Latvian Folktale Catalogue, the tale type is also registered in Latvia, with the title Trīs apelsīni ("Three Oranges"): the hero gains three oranges and releases the fruit maiden from the third one; another woman replaces her and turns her into a fish or dove.[67]

Slovakia[edit]

Variants also exist in Slovakian compilations, with the fruits being changed for reeds, apples or eggs. Scholarship points that the versions where the maidens come out of eggs are due to Ukrainian influence, and these tales have been collected around the border. The country is also considered by scholarship to be the "northern extension" of the tale type in Europe.[68]

A Slovak variant was collected from Jano Urda Králik, a 78-year-old man from Málinca (Novohrad) and published by linguist Samuel Czambel (sk). In this tale, titled Zlatá dievka z vajca ("The Golden Woman from the Egg"), in "Britain", a prince named Senpeter wants to marry a woman so exceptional she cannot be found "in the sun, in the moon, in the wind or under the sky". He meets an old woman who directs him to her sister. The old woman's sister points him to a willow tree, under which a hen with three eggs that must be caught at 12 o'clock if one wants to find a wife. After, they must go to an inn and order a hearty meal for the egg maiden, otherwise she will die. The prince opens the first two eggs in front of the banquet, but the maiden notices some dishes missing and perishes. With the third egg maiden, she survives. After the meal, the prince rests under a tree while the golden maiden from the egg walks about. She asks the innkeeper's old maid about a well, where the old maid shoves her into and she becomes a goldfish. The prince wakes up and thinks the old maid as his bride. However, the prince's companion notices it is not her, but refrains from telling the truth. They marry and a son is born to the couple. Some time later, the old king wishes for a drink of that well, and sends the prince's companion to fetch it. The companion grabs a bucket of water with the goldfish inside. He brings the goldfish to the palace, but the old maid throws the fish into the fire. A fish scale survives and lodges between the boards of the companion's hut. He cleans up the hut and throws the trash in a pile of manure. A golden pear tree sprouts, which the false princess recognizes as the true egg princess. She orders the tree to be burnt down, but a shard remains and a cross is made out of it. An old lady who was praying in church finds the cross and takes it home. The cross begins to talk and the old lady gives it some food, and the golden maiden from the egg regains human form. They begin to live together and the golden maiden finds work at a factory. The prince visits the factory and asks her story, which she does not divulge. He returns the next day to talk to her and, through her tale, pieces the truth together. At last, he executes the false bride and marries the golden maiden from the egg.[69]

Slovenia[edit]

In a Slovenian variant named The Three Citrons, first collected by author Karel Jaromír Erben, the prince is helped by a character named Jezibaba (an alternative spelling of Baba Yaga). At the end of the tale, the prince restores his fairy bride and orders the execution of both the false bride and the old grandmother who told the king about the three citrons.[70] Walter William Strickland interpreted the tale under a mythological lens and suggested it as part of a larger solar myth.[71] Parker Fillmore published a very similar version and sourced his as "Czechoslovak".[72]

Croatia[edit]

In a Croatian variant from Varaždin, Devojka postala iz pomaranče ("The Maiden out of the Pomerances"), the prince already knows of the magical fruits that open and release a princess.[73]

A Croatian storyteller from near Daruvar provided a variant of the tale type, collected in the 1970s.[74]

Ukraine[edit]

Professor Nikolai P. Andrejev noted that the tale type 408, "Любовь к трем апельсинам" or "The Love for Three Oranges", showed 7 variants in Ukraine.[75] The tale type is also thought by scholarship to not exist either in the Russian or Belarusian tale corpus,[76] since the East Slavic Folktale Catalogue, last updated in 1979 by Lev Barag, only registers Ukrainian variants.[77]

In a Ukrainian Carpathian variant titled A gazdag földesúr fia, the son of a rich nobleman wants to discover the world and leaves home. He finds work with an old woman and is paid with three eggs after three years' time. The youth opens each egg, each containing a maiden inside, the last of which he gives water to. The silver-haired egg maiden is replaced by a gypsy woman and goes through a cycle of transformations: goldfish, tree (sprouted from the fish scales), bedposts and a dove (when the bedposts are burnt). She regains her human form, is adopted by an old woman at the edge of the village. One day, she conceals her silver hair and goes to the castle with other women to work and sing, and reveals her tale.[78]

Baltic-German scholar Walter Anderson located a variant of tale type ATU 408 first collected by one Al. Markevic from students in Odessa, but whose manuscript has been lost. However, Anderson managed to reconstruct a summary of the tale: Ivan Carevič is looking for a bride of a special sort, one with no ascendants, nor descendents, with neither father, nor mother. He meets a kind old witch who directs him to dig up three graves in the steppe, his sought for bride will be found there, with a white kerchief on her head and golden hair under it. Ivan Carevic finds his bride, who is naked, and guides her up a willow tree, while he goes to fetch some clothes for her. While he is away, a gypsy woman appears, shoves the woman in the water and takes her place. After Ivan Carevic returns, the gypsy woman pretends to be her. As for the real bride, she turns into a fish which some fishermen bring to Ivan, but the gypsy woman asks for it to be cooked. It happen thus, but a scale falls in the ground near the stairs and an apple tree with many coloured fruits sprouts. The gypsy woman orders the tree to be burnt down so she can use its ashes in her bath, but a splinter survives and is taken by an old woman to her house. The girl comes out of the splinter to do chores for the old woman. She also sings songs and tells stories, which draws Ivan Carevič's attention. The prince then recognizes his true bride for her white kerchief and golden hair.[79] According to Christine Goldberg's work on the tale type, the story also belongs to the same cycle.[80]

Poland[edit]

In a Polish variant from Dobrzyń Land, Królówna z jajka ("The Princess [born] out of an egg"), a king sends his son on a quest to marry a princess born out of an egg. He finds a witch who sells him a pack of 15 eggs and tells him that if any egg cries out for a drink, the prince should give them immediately. He returns home. On the way, every egg screams for water, but he fails to fulfill their request. Near his castle, he drops the last egg on water and a maiden comes out of it. He goes back to the castle to find some clothes for her. Meanwhile, the witch appears and transforms the maiden into a wild duck. The prince returns and notices the "maiden"'s appearance. They soon marry. Some time later, the gardener sees a golden-feathered duck in the lake, which the prince wants for himself. While the prince is away, the false queen orders the cook to roast the duck and to get rid of its blood somewhere in the garden. An apple tree with seven blood red apples sprouts on its place. The prince returns and asks for the duck, but is informed of its fate. When strolling in the garden, he notices a sweet smell coming from the apple tree. He orders a fence to be built around the tree. After he goes on a trip again, the false queen orders the apples to be eaten and the tree to be felled down and burned. A few wood chips remain in the yard. An old woman grabs hold of them to make a fire, but one of the woodchips keeps jumping out of the fire. She decides to bring it home with her. When the old lady goes out to buy bread, the egg princess comes out of the woodchip to clean the house and returns to that form before the old lady comes home at night. This happens for two days. On the third day, the old lady discovers the egg maiden and thanks her. They live together, the egg maiden now permanently in human form, and the prince, feeling sad, decides to invite the old ladies do regale him with tales. The egg maiden asks for the old lady for some clothes so she can take part in the gathering. Once there, she begins to tell her tale, which the false queen listens to. Frightened, she orders the egg maiden to be seized, but the prince recognizes her as his true bride and executes the false queen.[81]

Polish ethnographer Stanisław Ciszewski (pl) collected another Polish variant, from Smardzowice, with the name O pannie, wylęgniętej z jajka ("About the girl hatched from an egg"). In this story, a king wants his son to marry a woman who is hatched from an egg. Seeking such a lady, the prince meets an old man who gives him an egg and tells him to drop it in a pool in the forest and wait for a maiden to come out of it. He does as he is told, but becomes impatient and breaks open the egg still in the water. The maiden inside dies. He goes back to the old man, who gives him another egg and tells him to wait patiently. This time a maiden is born out of the egg. The prince covers her with his cloak takes her on his horse back to his kingdom. He leaves the egg girl near a plantation and goes back to the palace to get her some clothes. A nearby reaper maid sees the egg girl and drowns her, replacing her as the prince's bride. The egg maiden becomes a goldfish which the false queen recognizes and orders to be caught to make a meal out of it. The scales are thrown out and an apple tree sprouts on the spot. The false bride orders the tree to be cut down. Before the woodcutter fulfills the order, the apple tree agrees to be cut down, but requests that someone take her woodchips home. They are taken by the bailiff. Whenever she goes out and returns home, the entire house is spotless, like magic. The mystery of the situation draws the attention of the people and the prince, who visits the old lady's house. He sees a woman going to fetch water and stops her. She becomes a snake to slither away, but the man still holds on to her. She becomes human again and the man recognizes her as the egg maiden. He takes her home and the false bride drops dead when she sees her.[82]

Germany[edit]

According to German scholar Kurt Ranke, the tale type registers seven German variants.[83]

Ranke also published a tale collected from a German source in Slovakia. In this tale, titled The Girl Out of the Egg, an unmarried lad dislikes the girls at his village and goes to look for one elsewhere. One time, when he is feeling hungry, he fetches three eggs from a nest and plans to eat them. When the breaks open the first one, a girl appears asking for water, but since he has none with him, she vanishes. The same thing happens to the second egg. When he cracks open the third one, he gives her water and leaves her to sit by a well, while he goes home to bring a carriage for her. When the departs, a witch and her gypsy daughter appear and steal the egg maiden's clothes, and she jumps in the well, changing herself into a fish. The gypsy girl passes herself off as the egg maiden, despite her ugliness, and lies that, if she eats the fish in the well, it will restore her beauty. The fish is killed and its bones are thrown away in the next farm, where a duck eats them and golden feathers grow on it. A woman in the farm plucks the duck and places the feathers in a pot. Soon, she discovers the egg maiden comes out of the feathers to eat a meal in her house, and delivers her from this from. Some time later, the egg maiden decides to go to the lad's house, where women and girls are stripping quills every day, in a shabby disguise. At the lad's house, the youth bids them tell stories, and the egg maiden, in disguise, tells hers. The lad recognizes her as his true bride, and tricks the gypsy girl's mother into pronouncing her own death sentence and her daughter's.[84]

Greece[edit]

Scholars Anna Angelopoulou and Aigle Broskou, editors of the Greek Folktale Catalogue, stated that tale type 408 is "common" in Greece, with 85 variants recorded.[85] According to Walter Puchner, Greek variants of the tale type amount to 99 tales, some with contamination with type 403A.[86]

Austrian consul Johann Georg von Hahn collected a variant from Asia Minor titled Die Zederzitrone. The usual story happens, but, when the false bride pushed the fruit maiden into the water, she turned into a fish. The false bride then insisted she must eat the fish; when the fish was gutted, three drops of blood fell to the floor and from them sprouted a cypress. The false bride then realized the cypress was the true bride and asked the prince to chop down the tree and burn it, making some tea with its ashes. When the pyre was burning, a splinter of the cypress got lodged in an old lady's apron. When the old lady left home for a few hours, the maiden appeared from the splinter and swept the house during the old woman's absence.[87] Von Hahn remarked that this transformation sequence was very similar to one in a Wallachian variant of The Boys with the Golden Stars.[88]

Romania[edit]

Writer and folklorist Cristea Sandu Timoc noted that Romanian variants of the tale type were found in Southern Romania, where the type was also known as Fata din Dafin ("The Bay-Tree Maiden").[89]

In a Romanian variant collected by Arthur and Albert Schott from the Banat region, Die Ungeborene, Niegesehene ("The Not-Born, Never Seen [Woman]"), a farmer couple prays to God for a son. He is born. Whenever he cries, his mother rocks his sleep by saying he will marry "a woman that was not born nor any man has ever seen". When he comes of age, he decides to seek her. He meets Mother Midweek (Wednesday), Mother Friday and Mother Sunday. They each give him a golden apple and tell him to go near a water source and wait until a maiden appears; she will ask for a drink of water and after he must give her the apple. He fails the first two times, but meets a third maiden; he asks her to wait on top of a tree until he returns with some clothes. Some time later, a "gypsy girl" comes and sees the girl. She puts a magic pin on her hair and turns her into a dove.[90]

In another Romanian variant, Cele trei rodii aurite ("The Three Golden Pomegranates" or "Three Gilded Pomegranates"), a prince throws a stone at a old woman's jug, breaking it, and she curses him to never marry until he finds the three golden pomegranates. Wondering about the old woman's words, he decides to venture into the world and seek such fruits. He passes by three hermit women who direct him to a garden guarded by its guardians: a dragon (which he greets), a baker woman cleaning an oven (to whom he gives a rag), a dirty and slimy well (which he cleans off) and a gate covered with cobwebs (which he cleans). He steals the three pomegranates and rushes back to the hermit woman, and the garden trembles to alert its guardians to stop him, but, due to the prince's kind actions, he leaves unscathed. The prince returns home and opens each of the fruits on the way: from each a woman comes out and asks for water; he cannot give water to the first two, who die of thirst. The third girl survives for the prince gives her water, and guides her up a tree, while he goes to the castle to bring his father to meet her. While he is away, a gypsy girl finds the fairy maiden, sticks a pin in her hair, turns her into a golden bird, and takes her place. The fairy maiden, in bird form, is later killed and cooked, but a fir tree sprouts from its blood, which the false bride orders to be felled. A beggar woman watches the fir tree being chopped down and takes with her a splinter to her home to use as pot lid. The fairy maiden comes out of the splinter to do chores for the beggar woman, is found out by the beggar and adopted as her daughter. One day, the fairy maiden asks the beggar woman to buy some linen, which she uses to sew scarves with images of her story. The scarves are given to the prince, who realizes the gypsy girl's deception and executes her. He then takes the fairy maiden to the castle and marries her.[91][92]

Bulgaria[edit]

The tale type is also present in Bulgaria, with the name "Неродената мома" or "Неродена мома" or Das ungeborene Mädchen[93] ("The Maiden That Was Never Born"),[94] with 21 variants registered.[95] A later study gives a higher number of 39 variants in archival version.[96]

According to the Bulgarian Folktale Catalogue by Liliana Daskalova-Perkovska, the girls may appear out of apples, watermelons or cucumbers,[97] and become either a fish or a bird.[98]

Cyprus[edit]

At least one variant from Cyprus, from the "Folklore Archive of the Cyprus Research Centre", shows a merger between tale type ATU 408 with ATU 310, "The Maiden in the Tower" (Rapunzel).[99]

Malta[edit]

Maltese linguist George Mifsud Chircop stated that the story ‘is-seba’ trongiet mewwija’ is popular in Malta and Gozo.[100]

In a variant from Malta, Die sieben krummen Zitronen ("The Seven Crooked Lemons"), a prince is cursed by a witch to find the "seven crooked lemons". On an old man's advice, he grooms an old hermit, who directs him to another witch's garden. There, he finds the seven lemons, who each release a princess. Every princess asks for food, drink and garments before they disappear, but the prince helps only the last one. He asks her to wait atop a tree, but a Turkish woman comes and turns her into a dove.[101]

In a Maltese variant collected by researcher Bertha Ilg-Kössler with the title Die sieben verdrehten Sachen ("The Seven Crooked Things"), a king promises to build a fountain of some liquid for the poor if he is blessed with a son. His prayers are answered. The prince grows up and scares an old woman who has come to the fountain. The old woman curses him to burn with love and never rest until he finds "The Seven Crooked Things". The prince travels high and low until he meets a Turkish bakerwoman who gives the prince seven fruits that look like dry nuts.[102]

Yiddish[edit]

In a Yiddish folktale from Russia, The Princess of the Third Pumpkin, an old woman tells the royal couple and the prince to seek a garden with three pumpkins. The prince goes to this garden, gets the gourds and opens each one; a maiden coming out of each one. Only the third is given water. The prince makes her wait while he goes back to the castle. A "gypsy woman" appears, shoves the pumpkin girl into a well and replaces her as the prince's beloved. Meanwhile, the girl becomes a fish in the well, is killed, and its scales are used into a pair of shoes. The old woman sees that the girl comes out of the fish scales to clean her house.[103]

Caucasus Region[edit]

According to scholars Isidor Levin and Uku Masing, tale type 408 is "rare" in the Caucasus, with little more than 5 variants reported.[104]

Azerbaijan[edit]

In an Azeri tale published by Azeri folklorist Hənəfi Zeynallı with the title "Девушка из граната" ("The Girl from the Pomegranate"), a prince dreams of a maiden in a pomegranate. He decides to seek her out. He visits three dev mothers, who indicate the way to the garden. He takes the three pomegranates and leaves the garden. The first two fruits yield nothing, but the third releases the maiden. He asks the girl to wait nearby a tree, while he goes back to the kingdom. A slave girl sees the maiden, shoves her down the well and replaces her. The girl becomes a rosebush, a platane tree and a tree splinter. The splinter is found by a man and brought to his home. The fruit maiden comes out of the splinter to do household chores and is discovered by the man. One day, the prince summons all women to his yard for them to tell him stories, and the fruit maiden sings about her story while weaving and counting pearls.[105] The compiler sourced the tale from an informant in Nakhkray (Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic), and classified the tale as type 408.[106]

In another Azeri tale collected from Nakhkray with the title "Женщина, вышедшая из камыша" ("The Wife from the Reeds"), a king has a son. One day, the prince tells his father he had a dream he would marry a woman from the djinns, and decides to look for her. He consults with an old woman in the city, and the old woman advises him to take provisions for a seven-month journey, ride all the way to the west, where he will meet a div with a blister on his leg; the prince is to pierce the blister, hide and wait for the div to swear on his own mother's blood not harm his helper. The prince heeds her words and journeys west to meet the div; he pierces the leg blister, and the div wakes up in pain. The div swears on his mother's name not to harm the person, and the prince presents himself and explains the reason for his journey. The div then directs him to a river with three reeds, where he is to cut one and only open it at home, not on the way. The prince follows the div's advice, but, nearing his home, he cuts open the reed: a beautiful girl comes out of it, but admonishes him for disobeying the div's orders. Still, the prince is enchanted with the girl and helps her climb a plane tree, while he goes back home and bring a retinue to properly welcome her. As he leaves, and time passes, the girl becomes thirsty and sees a black girl coming with some dishes to wash. The girl asks for some water, but the black girl shoves her into the sea and takes her place up the plane tree. The prince comes back and takes the black girl into the palace, thinking her to be the reed girl. As for the reed girl, she becomes a fish that is captured and brought to the prince, and begins to sing to him. The false bride orders the fish to be cooked and that no drop of its blood is to fall on the ground. The cook follows the orders, but the fish's blood drops on the ground and a plane tree sprouts. The tree uses its leaves to caress the prince when he passes by, and the false bride also wants it chopped down. A splinter of the plane tree survives and is taken by an old woman to her house. The reed girl comes out of the splinter to do chores at the old woman's house, but is discovered and adopted by the old woman. Time passes, the reed girl dies, and the old woman, fulfilling her last request, places her body in a tomb. One day, the prince passes by the tomb and hears someone calling for him from within. He returns to the tomb some days later and finds the reed girl, alive. The reed girl tells him her adventures, and says the black girl has a key around her neck, which is to be returned to the reed girl. The prince returns the key to the reed girl, punishes the false bride and marries her.[107] The tale was also classified by the compilers as type 408.[108]

Georgia[edit]

In a Georgian tale titled "კიტრის ქალი" ("ḳiṭris kali"), translated into Hungarian with the title Az uborkalány ("The Cucumber Girl"), an old woman curses a prince to not rest until he finds the cucumber girl. He travels to another kingdom and steals a cucumber from a royal garden. When he cuts open the vegetable, a girl appears. He takes her to the border of his kingdom and goes to the castle, but the girl from the cucumber warns him against it. An Arab girl appears, trades clothes with her and throws the maiden in the well. The cucumber girl goes through a cycle of transformations (goldfish, then a silver tree, then tree splinter, and human again). She appears out of the tree splinter to clean an old woman's house, and goes to the castle with other woman to tell stories to the prince. The cucumber girl tells her tale and the prince notices the deception.[109][110]

In another Georgian tale, "ლერწმის ქალი" ("lerc̣mis kali"), translated as The Reed Lady, the king's son goes after a bride for himself and finds three reeds in the sea. He takes them back to his kingdom, releases a "reed lady". Eventually, an Arab woman throws her in the water and replaces her as the king's son's bride. The reed lady goes through a cycle of reincarnations (fish to tree to human), and the Arab woman orders her rival's form to be destroyed in order to hide her crime, but the reed lady survives in the shape of a tree chip brought home by an old lady. The reed lady comes out of the chip and performs chores for the old lady, who discovers her and adopts her. The reed lady eventually goes to a gathering to tell her story, through which the king's son recognizes her and punishes the Arab woman.[111][112][e]

Armenia[edit]

In an Armenian tale titled "Сказка о небывалом огурце" ("The Tale of the Fantastic Cucumber"), translated as The Extraordinary Cucumber, a large cucumber appears in a man's garden, who sells it to the prince, with a piece of advice: take the vegetable and keep walking until he reaches a sycamore, but do not look back. The prince heeds the man's words and hears voices telling him to look behind him, but he presses on until he reaches a plane tree. He then takes a knife to cut open the cucumber, and out comes a beautiful golden-haired maiden. He falls in love with her on the spot and guides her up the plane tree, where she is to wait until he returns for her. He goes back to the palace, leaving the maiden unprotected: an old woman sees the girl's shadow in a spring behind the tree and tries to convince the girl to come down, but she refuses. The old woman then transforms the girl into a bird, changes her shape into the girl and tricks the prince. Later, the girl, as bird, flies over the prince and his friends, but the prince snaps its neck and throws it in a garden. On its place, a mulberry tree sprouts, which the garden's owner chops down, but a large splinter the size of a spoon flies over to a poor woman's yard. The poor woman finds the spoon and brings it home; when she leaves, the cucumber maiden comes out of the spoon, cleans the house and prepares the food, then turns back into the spoon. The poor woman discovers her presence and adopts her as her daughter. Later, the king orders that every house is care for and feed one of the king's horses. In the poor woman's house, the cucumber maiden feeds and grooms the horse; the prince comes to fetch the horse and sees the poor woman's daughter, which he notices is a lookalike of the cucumber girl. The next day, the prince orders that one person from every household shall come to the palace to comb wool. The cucumber maiden goes with the others and they finish the task. The prince then offers a reward, and the maiden asks for a ripe pomegranate, a little doll and a sharp razor. Despite the strangeness of the request, the prince produces the objects, which the maiden takes with her to a deserted road. The cucumber maiden then begins to tell her sorrows to the objects: the pomegranate bursts in response to her story, the doll dances and the razor greatly sharpens, but before she does anything, the prince finds her and takes her to the palace. He punishes the sorceress and marries the true cucumber maiden.[114][115]

Author A. G. Seklemian published an Armenian tale titled Reed-Maid. In this tale, a king insists his unmarried son finds a wife, and the prince retorts that he will only marry a maiden "not begotten of father and mother". Pondering on the words, the king travels far and wide, asking people if they know of such a maiden. A hermit tells the king about a river in a forest where reeds grow near the shore. The king is to choose the best looking one and cut it off with a golden pocket-knife. The king follows the hermit's instructions, finds a reed and releases a beautiful maiden for his son. He leaves the girl, named Reed-maid, atop a tree, while he goes to fetch maidservants and clothes for her. As the king departs, a gypsy girl from a nearby gypsy camp sees the Reed-maid and wants to take her place: she shoves the reed maiden inside the river and waits for the king's arrival. When the monarch arrives, he finds that his prospective daughter-in-law has changed appearance, but falls for the false reed-girl's excuses. The false bride claims to the prince she is the reed maiden his father procured, but he does not believe her. As for the true maiden, she goes through a cycle of reincarnations: on the spot she was drowned, a silver fish with gold fins appears, which the gypsy woman orders to be cooked; one of the fish bones remains and is discarded in the garden, where a beautiful tree sprouts; the gypsy orders the tree to be felled and burnt, but a chip survives and is flung off to the cabin of a poor old woman, which she takes as a pot lid. The next days, when the old woman leaves, the reed maiden gets out of the chip to do chores and returns to that form after. The old woman finds out who is doing chores at her house and adopts the reed-maid as her daughter, who says she cannot reveal her origins yet. Later, the old woman sells embroideries sewn by the reed-maid, which the prince notices to be very beautiful and demands to know its maker. The old woman consults with the reed-maid, who tells her to invite them to the cabin for a meal. It is done as the reed-maid requests, and the prince, his father and the false bride attend the occasion. After the meal, the king suggests the maiden regales them with a story, which she agrees to do: she places a dry grapevine and a dove prepared to be cooked on the table, then claims that, if her story is true, the vine will yield fresh grapes and the dove will be cooked without fire. The reed-maiden then narrates the tale of the king who searched for a wife for his son, and, when she finishes, the vine yields fresh fruits and the dove is cooked, confirming her identity as the true reed-maid. The gypsy is then executed.[116]

Ossetia[edit]

In an Ossetian tale titled "Сказка о нерождённой" ("Tale of the Unborn One"), a malik and his wife have a son, and die some time later. One day, a kulbadagus's daughter brings ten pots in her hands to fetch some water from a fountain in the malik's property, and the malik's son, who is practicing his archery skills, shoots arrows and breaks the pots. The kulbadagus's daughter returns to her mother and complains about it, and she says the next time the malik's son shoots his arrows at her, curse him to seek for his wife a girl no mother has given birth to. It happens thus, and the malik's son becomes obsessed with finding this mysterious girl. He journeys far and wide, and meets with other kulbagadus in his quest, until he gets the first clue about such a girl: such girls live in the bottom of the sea, where there are three trees. The malik's son, joined by a hound, dives to the bottom of the sea, cuts down the middle tree and brings it with him. He journeys back to a female kulbadagus who wishes to have him for son-in-law, and her daughter keeps pestering the youth with questions about the tree trunk he brought with him. Annoyed at her growing insistence, the malik's son chops down the trunk and a golden-haired maiden steps out of it. The female kulbadagus's daughter marvels at the tree maiden's beauty and convinces the youth to go back home and bring musicians and a retinue for his soon-to-be bride. As he departs, the female kulbadagus's daughter strips the tree maiden, cuts her hair and shoves her in the water, then takes her place by putting on the clothes and the hair. As for the tree maiden, she becomes a goldfish when she falls into the water, and is later killed to be prepared for a meal for the false bride. With the help of a poor old woman in the village, the tree maiden, as the fish, asks her to fetch a few drops of her blood in an apron and bury it near the malik's son's house. The old woman follows her instructions and, out of the drops of blood, spring two apple trees bearing golden fruits. The false wife orders the trees to be made into firewood, and they are promptly chopped down. However, a splinter remains and falls into the poor woman's house. The tree maiden comes out of the splinter to sweep the house and prepare the food and is discovered by the old woman, who adopts her. Later, the tree maiden uses her magic powers to create a large house for the poor woman, and bids her invites the malik's son and his wife there. After three times, the malik's son goes to the poor woman's house for a meal, and the tree maiden tells her life story. The malik's son recognizes her and punishes the false wife.[117]

Asia[edit]

The tale is said to be "very popular in the Orient".[118] Scholar Ulrich Marzolph remarked that the tale type AT 408 was one of "the most frequently encountered tales in Arab oral tradition", albeit missing from The Arabian Nights compilation.[119]

Middle East[edit]

Scholar Hasan El-Shamy lists 21 variants of the tale type across Middle Eastern and North African sources, grouped under the banner The Three Oranges (or Sweet-Lemons).[120] Variants have been collected from Palestine (jrefiyye, or 'magic tale' titled Las muchachas de las toronjas, or "The Girls from the Toranjs"),[121] and Lebanon (with the title Die drei Orangen, or "The Three Oranges").[122]

Syria[edit]

In a Syrian tale collected by Uwe Kuhr with the title Drei Zitronen ("Three Lemons"), a prince has a dream about a maiden, and desires to marry her. He rides to the beach and embarks on a ship to another country. In this land, he meets a woman tearing leaves from a tree, and she explains every leaf is the life of one that dies. The woman directs him to her sister. The prince meets a second old woman who is sewing clothes and whenever she finishes a person is born. The second old woman gives the prince three lemons and tells him to open each one. The prince makes the journey back and cuts open the first two: a maiden springs out of each one, but disappears soon after. Finally, the prince comes near his father's palace and cuts open the last lemon: a maiden comes out to whom the prince gives water. The prince asks her to climb a tree and wait for him. As he leaves, an ugly servant comes out of the palace to wash the king's clothes, sees the lemon girl's reflection in the water, and turns her into a brown-feathered bird, taking her place on the tree. The servant passes herself as the lemon girl, and marries the prince. The brown-feathered bird flies to the prince's window, and the false bride wrings its neck. The bird's blood drops to the ground and three lemon trees sprout. The prince orders the trees to be fenced in until their lemons are ripe. At the end of the tale, the prince takes the lemons to his chambers, cuts open the third one and the lemon girl appears to him. He notices the deception and kills the false bride.[123]

Iran[edit]

According to a study by Russian scholar Vladimir Minorsky, the tale type appears in Iran as Nâranj o Toronj, wherein the prince searches for the "Orange (Pomegranate) Princess".[124] Later, German scholar Ulrich Marzolph, in his catalogue of Persian folktales (published in 1984), located 23 variants of the tale type in Iran, which is listed as Die Orangenprinzessin ("The Orange Princess").[125] In these tales, the fruit maidens appear out of apples, pomegranates, bitter oranges, or some other type of fruit from a tree guarded by evil creatures (in some tales, the divs). The fruit maidens also go through a death and rebirth cycle.[126]

Author Katherine Pyle published the tale The Three Silver Citrons and sourced it as a Persian tale. In this story, a dying king begs his three sons to look for wives. The two elders ride on a road and see a passing beggar. The man begs for food other than black bread, but the two princes refuse to give him. They find normal wives for themselves. The third prince meets the same beggar man and gives him some food. In return, he is gifted with a magical pipe that summon little black "trolls" as helpers. The prince asks the trolls where he can find the loveliest princess in the world, and the small creatures take him there. They reach a castle the prince enters alone; in a chamber, he meets three maidens that, frightened by his presence, become three silver citrons. The prince takes all three fruits and leaves the castle.[127]

Another Persian variant, The Orange and Citron Princess, was collected by Emily Lorimer and David Lockhart Robertson Lorimer, from Kermani. In this tale, the hero receives the blessing of a mullah, who mentions the titular princess as "The Daughter of the Orange and the Golden Citron". The hero's mother advises against her son's quest for the maiden, because it would lead to his death. The tale is different in that there is only one princess, instead of the usual three.[128]

In an Iranian tale collected by orientalist Arthur Christensen with the title Goldapfelsins Tochter ("The Golden Orange Daughter"), a king promises to build a fountain of honey and butter that the poor can collect if his son's health improves. It so happens. One day, a poor old woman comes to the fountain to get some butter and honey, but the prince frightens the woman by playing a prank on her: he shoots an arrow at an egg she is carrying. The old woman curses the prince to fall in love and to seek the Golden Orange Daughter. The prince's curiosity is piqued and he asks the old woman where he can find her. The old woman answers that in the country of peris and devs, an orange tree holds fruits with a young woman inside. The prince takes seven oranges from a garden guarded by Divs. he cuts open the first six fruits; a maiden appears out of it, asking for bread and water, but, since the prince is on the road and far from any city, she dies. The seventh maiden is given bread and water, but appears in black garments - she explains to the prince she is mourning for the other maidens, her sisters. A black maidservant kills the orange maiden and takes her place, while she becomes a lovely little bush, from which she exits to act as the mysterious housekeeper for an old washerwoman. Later, the orange maiden, named Nänä Gâzor, and other women are invited to the castle to tell stories and work.[129]

Another "very famous" Iranian tale is Dokhtar-e Naranj va Toranj ("The Daughter of the Orange and the Bergamot"), which largely follows the tale sequence, as described in the international index: a childless king promises to build a fountain for the poor. The prince is born and humiliates an old woman, who curses him to burn with love for a fruit maiden. This fabled girl can only be found in a garden in a distant land. The prince gets the fruits, opens it near the water and a beautiful girl comes out of it. He leaves the girl near a tree, until an ugly slave comes, kills the fruit maiden and replaces her. The ugly slaves passes herself off as the fruit maiden and marries the prince. However, her rival is still alive: she becomes an orange tree, which the slave wants chopped down and made into furniture.[130]

Professor Mahomed-Nuri Osmanovich Osmanov (ru) published an Iranian tale with the title "Померанцевая Дева" ("The Pomerance Girl"). In this tale, the childless padishah promises to build a fountain of honey and butter for the poor. God hears his prayers and a son is born. Twenty years later, when an old woman goes to the fountain to fetch some butter and honey, the prince says it is empty. Disappointed, the old woman tells the prince to look for the titular Pomerance Girl. The girl is the daughter of the Padishah of the Peris, and lives as a fruit in a distant garden, guarded by divs. The prince takes three pomerances and opens each one; out comes a maiden asking for water and bread. Only the third survives because he gives her food and drink.[131]

Russian Iranist Alexander Romaskevich (ru) collected another Iranian tale in the Jewish-Iranian dialect of Shiraz with the title "Жена-померанец и злая негритянка" ("The Orange-Wife and the Evil Black Woman").[132]

Iraq[edit]

Author Inea Bushnaq published an Iraqi variant titled The Maiden of the Tree of Raranj and Taranj. In this tale, a childless king prays to Allah to have a son. The queen does the same: if her prayers are answered, she shall have fat and honey flow through the kingdom. Their prayers are answered, but the queen forgets to fulfill her promise, until the young prince has a dream in which a person tells the boy to remind his mother of her promise. The fountains are built. One day, an old woman fetches some fat and honey in her bowl. From his window, the prince shoots an arrow at the woman's bowl, which breaks apart. The old woman curses the prince to search for the "Maiden of the Tree of Raranj and Taranj", who, the prince learns, is hidden in a tree in a garden watched over by djinns.[133]

In an Iraqi tale published by professor B. A. Yaremenko with the title "Раранджа и Транджа" ("Raranja and Tranja"), a childless woman makes a vow to Allah to dig two ditches and fill them with honey and butter for the people. As time passes, her prayers are answered, and she and her husband have a golden-haired son. One day, a very old woman approaches him while he is playing with friends and tells the boy to remind his mother of her promise. The boy returns home and tells his mother about the incident. Afraid something might happen to her son, she hires builders to excavate two ditches and fill it with honey and butter, then invites the people to partake of her offerings. The same old woman takes her jug and goes to fetch some for her, but can only find some remains which she places in her jug. As she walks home, the boy tumbles into her and she drops her jug. In anger, she curses the boy to burn with love for the "raranja and tranja" ('sour lemon and bitter oranges'). The boy then becomes fascinated with such a thing and, years later, decides to look for her. He rides his horse to a crossroads and finds an old man who points him to the right direction. Then, he meets a giant woman working at a mill and making flour; he takes some of the flour and suckles on the giantess's breasts in order to gain her trust. After he explains the reason for his journey, the giantess tries to dissuade him, for the path ahead if full of monsters that guard the "raranja and tranja". Despite her warning, he soldiers on, plucks three fruits and begins hid ride home. Homewards, he hears a voice saying it wants water; the first fruit falls down from his bag into the ground in a rotten state, and so does the second one. When he hears a third time a voice, he rushes to a stream and drops the fruit there, and out comes a golden-haired maiden. He takes her with him next to his home village and leaves her up a tree near a stream, while he looks for some food for her. As he goes away, an old witch appears with some dirty dishes, sees the maiden's reflection in the water, mistakes it for her own reflection, and goes to complain to her mistress. She returns to the maiden on the tree, sticks a needle on her, turning her into a little bird, and takes her place. After the youth returns, the witch passes herself off as the fruit maiden. As for the real one, she flies into her beloved as a bird, but the false bride kills it. In the place where the bird's blood landed, springs a lotus tree (which Yaremenko explains is a wild jujube) of green and gold colour and studded with pearls. The false wife demands the tree be made into a cradle for her unborn child, and it happens so. After the witch places the baby on the cradle, the child cries in pain, and the witch gets rid of the cradle by selling it to a poor woman. At the poor woman's house, the fruit maiden comes out of the cradle to do the dishes and clean the house, and is eventually found out by the poor old woman. The old woman promises to keep her secret. Later, the witch realizes the cradle she sold had pearls in it, buys it back and orders the maidens in the village to come and sew a pearl-studded dress for her. The fruit maiden joins with the other girls in the activity and tells her story while stringing pearls together. The youth realizes she is the true fruit maiden, and takes her with him to his home village.[134]

Kurdish people[edit]

In a Kurdish tale titled The Eggs of the Ancient Tree, a padishah's son goes to a secret garden protected by creatures in order to fetch three eggs from a tree. After he takes three eggs, the tree they were on begins to ring out loud, and he escapes on a horse from the garden. He stops by a tree near a river and breaks each of the eggs: the first two cry out for "bread and water", then disappear. He then breaks the third egg and fulfills its request. A beautiful peri maiden comes out of the egg, who the prince places up a nearby tree while he goes back to the palace to bring the bridal party (berbûk) to welcome her as his bride, and leaves her there. Meanwhile, two old traveling women see the perî's reflection in the water and fight against each other, wanting the beautiful visage for themselves. The perî maiden, watching the scene and pitying the rowing women, says from her location that the reflection is hers, to quell their fighting. The vagabond women sight the perî and one of them climbs up the tree, then tricks the fairy into giving her clothes. After the perî naïvely does so, the vagabond women take the fairy down the tree so they could see their visages in the water, and shove her into the river, and "nature blossomed", with trees and flowers everywhere. One of the women leave, while the other, wearing the perî's clothes, remains. The prince's berbûk arrives, and everyone marvels at the flowers instead of the false bride, who is rude to them. Despite some reservation, the bridal party brings back the false bride and she marries the prince. Soon after, the peri maiden goes through a cycle of reincarnations: the flower the bridal party brought with them falls to the ground and becomes a poplar tree that the false bride wants to be made into a cradle for her baby; later, the false bride orders the cradle to be burnt down. Her orders are carried out. One day, an old woman comes to the palace to borrow some coals, and finds an egg amid the ashes, which she brings home and places in a wooden basket. In her house, after the old woman leaves, the perî comes out of the egg, does the chores, then returns to her previous form. The old woman discovers her and adopts her. Later, the padishah's son gives donkeys to every house to be taken care of, and the woman takes an ugly-looking one per the perî's request. The perî feeds the donkey until it becomes healthy, and the padishah's son orders his soldiers to collect the animals back to the royal stables. To the soldiers' surprise, the lame-looking donkey is indeed healthy, but, at the palace, it sits down and does not move (which it was instructed to do by the perî). The padishah's son wants some explanation, and the old woman says her daughter was the one that cared for the animal, but she will only come if the prince fills the path with featherbeds. After the maiden's request is carried out, the perî comes to the palace in fine clothes and the prince recognizes her.[135]

Turkey[edit]

In the Typen türkischer Volksmärchen ("Turkish Folktale Catalogue"), by Wolfram Eberhard and Pertev Naili Boratav, tale type ATU 408 corresponds to Turkish type TTV 89, "Der drei Zitronen-Mädchen" ("The Three Citron Maidens").[136][137] Alternatively, it may also be known as Üç Turunçlar ("Three Citruses" or "Three Sour Oranges").[138] The Turkish Catalogue registered 40 variants,[139] being the third "most frequent folktale" after types AT 707 and AT 883A.[140]

In Turkish variants, the fairy maiden is equated to the peri and, in several variants, manages to escape from the false bride in another form, such as a rose or a cypress.[141] In most of the recorded variants, the fruits are oranges, followed by pomegranates, citrons, and cucumbers in a few of them; then apples, eggs or pumpkins (respectively in one variant each).[142][143]

Hungarian folklorist Ignác Kúnos published a Turkish variant with the title A három narancs-peri, translated into English as The Three Orange-Peris.[144][145] The tale was also translated as The Orange Fairy in The Fir-Tree Fairy Book.[146]

In a Turkish tale collected in the Ankara province with the title The Young Lord and the Cucumber Girl, a young lord takes his horse to drink water from a fountain and the animal accidentally steps on the foot of a witch. For this, she curses the young lord to burn with love for a cucumber girl. He tells his father, the bey, of his longing, and decides to ride away to find this girl. He takes shelter with a man with a long beard and his daughter. Both give instructions to the lord how he can reach the orchard with the cucumbers. He warns them to open the cucumbers near a body of water, lest the girls that come out of will die of thirst. The young lord follows the instructions and gets the cucumbers. On his way back, he opens the first two vegetables in desert places, and the girls die. He reaches a fountain next to the city and cracks open the last cucumber, giving water to the girl. The cucumber girl asks the young lord to hold a 40-day wedding celebration, then return to fetch her, since she will be waiting on top of a poplar tree. After the lord leaves, an ugly woman appears with pitchers and mistakes the image of the cucumber girl for her own reflection, and stops working, breaking the pitchers. Her family chastises her and she goes to the fountain, where she notices the girl on the tree. She convinces the girl to climb down so she would delouse the girl's hair, but she plucks a strand of white hair (the girl's vital spot) and she dies. When she dies, a sesame plant sprouts. The young lord returns and is tricked by the ugly woman, who passes herself off as the cucumber girl. As for the girl, she passes by a cycle of reincarnations: first, into a sesame plant, which is tossed in the fire; then to two pigeons, who are captured and killed; third, to a poplar tree where the birds are buried, which is cut down to make a crib for the woman's child; then to a single chip that is taken by an old woman. The cucumber girl comes out of the wooden chip to clean the woman's house, and is discovered, being adopted by her. Later, during a famine, the lord sends his horses to each house, even to the old woman's, to be taken care and fed. The cucumber girl feeds and grooms the lord's horse for a while, and, when the lord goes to get it back, he finds out the truth from the reborn cucumber girl.[147]

Afghanistan[edit]

In an Afghan tale from Herat, The Fairy Virgin in a Pumpkin, a prince goes to a garden to pick up exquisite pumpkins and brings them home. He cuts open one of them and out comes a fairy maiden, who complains to him. He walks a bit more and rests by a canal. He decides to cut open the second pumpkin and out comes a second fairy maiden. She says she is naked and asks him to bring her some clothes. Since she is naked and anyone might see her, she climbs up a tree. While the prince is away, the fairy maiden protects the Simurgh's nest from a snake attack. Soon after, an ugly maidservant appears and sees a beautiful face reflected in the water - the fairy's. Thinking it is her own, she goes back to her master and says she will not work for him anymore. Her master beats and expels her. The maidservant sees the fairy maiden on the tree. Suddenly, the tree splits open, the fairy maiden enters it, and it closes again. The maidservant replaces her and marries the prince. One day, she asks for the tree to be used to make a cradle for her daughter. Sensing it is the fairy maiden, somehow still alive, she orders the cradle to be burnt to cinders. An old woman gathers some leftover wood and cotton and takes them home. The fairy maiden comes out of the wood and the cotton to help the old woman spin and do the chores. One day, the prince summons all maidens to his yard to string a pearl necklace for his daughter. The fairy maiden is invited and the prince recognizes her.[148]

Central Asia[edit]

Researcher Aziza Shanazarova summarized a narrative from the Central Asian work Maẓhar al-ʿajāʾib by a Sufi scholar, dated to 16th century. In this tale, titled The Story of the Patience Stone, a prince of Qanshīrīn wants a beautiful wife, and journeys to a "hidden realm" where he is given three loaves of bread, for him to open near water. On his journey back, the prince breaks open the first bread, a beautiful woman appears out of it, asks for water, but dies of thirst soon after. After a while, he opens the second loaf, another woman appears and dies due to lack of water. Finally, the prince opens the last loaf near a water source, a third woman appears and drinks some water. The prince takes her to Chahār Bāgh ('Four Gardens') and leaves her up a tree, while he goes to the city. Meanwhile, an enchantress kanīzak ('servant') from Kashmīr goes to fetch water and sees the bread woman reflection in a magical pool, thinking it is her own. The bread lady laughs at the servant and is thrown in the magical pool, while the servant takes her place and marries the prince. As for the bread lady, she survives being in the pool by the ghawth-i aʿẓam ('the greatest sustenance'), who gives her a key that allows her to leave the pool, and she makes her way to the city to find a pīr ('master') and a sang-i ṣabr ('stone of patience') to which she is to tell her secrets. The bread lady meets the pir, who adopts her. Later, the prince, increasingly suspicious of his false bride, becomes ill and asks his subjects to bring him food. One day, he gets a dish with a peeled mung bean (mash-i muqashshar), prepared by the pir's daughter. The prince eats the dish and goes to meet the pir, who is wearing a veil to conceal her identity. The veiled lady asks the prince to bring her the patience stone. The prince does as asked and people gather to see the event: the veiled lady places the patience stone on a bowl of milk and asks it to retell her story. The stone narrates the veiled lady's story until the milk becomes blood and the stone bursts open, revealing a white stone inside that hits the servant's head, killing her. The lady removes the veil and reveals herself to the prince as the woman from the bread and they marry.[149] According to Shanazarova, the tale is contained in a copy of Maẓhar al-ʿajāʾib, catalogued as MS 8716 and dated to the year 1766.[150]

Japan[edit]

Japanese scholarship argues for some relationship between tale type ATU 408 and Japanese folktale Urikohime ("The Melon Princess"), since both tales involve a maiden born of a fruit and her replacement for a false bride (in the tale type) and for evil creature Amanojaku (in Japanese versions).[151][152] In fact, professor Hiroko Ikeda classified the story of Urikohime as type 408B in his Japanese catalogue.[153]

Americas[edit]

United States[edit]

According to William Bernard McCarthy, the tale type appears in French-American and Iberian-American tradition.[154]

Brazil[edit]

In a Brazilian variant collected by lawyer and literary critic Silvio Romero, A moura torta, a father gives each of his three sons a watermelon and warns them to crack open the fruits near a body of water. The elder sons open their watermelons, a maiden appears out of each and asks for water or milk, then, unable to sate her thirst, dies. The third brother opens his near a spring and gives water to the maiden. Seeing that she is naked, he directs her to climb a tree while he returns with some clothes. A nearby moura (Moorish woman) sees the maiden's reflection in the water, notices the maiden on the tree and turns her into a dove by sticking a pin on her head.[155]

Popular culture[edit]

Theatre and opera[edit]

The tale was the basis for Carlo Gozzi's commedia dell'arte L'amore delle tre melarance,[156] and for Sergei Prokofiev's opera, The Love for Three Oranges.

Hillary DePiano's play The Love of the Three Oranges is based on Gozzi's scenario and offers a more accurate translation of the original Italian title, L'amore delle tre melarance, than the English version which incorrectly uses for Three Oranges in the title.

Literature[edit]

A literary treatment of the story, titled The Three Lemons and with an Eastern flair, was written by Lillian M. Gask and published in 1912, in a folktale compilation.[157]

The tale was also adapted into the story Las tres naranjitas de oro ("The Three Little Golden Oranges"), by Spanish writer Romualdo Nogués.[158]

Bulgarian author Ran Bosilek adapted a variant of the tale type as his book "Неродена мома" (1926).[159]

Television[edit]

A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék ("Hungarian Folk Tales") (hu), with the title A háromágú tölgyfa tündére ("The Fairy from the Oak Tree"). This version also shows the fairy's transformation into a goldfish and later into a magical apple tree.

See also[edit]

- Lovely Ilonka

- Nix Nought Nothing

- The Bee and the Orange Tree

- The Enchanted Canary

- The Lassie and Her Godmother

- The Myrtle

- The King of the Snakes

- Sandrembi and Chaisra

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ "The motif of a woman stabbed in her head with a pin occurs in AT 403 (in India) and in AT 408 (in the Middle East and southern Europe)."[17]

- ^ As Hungarian-American scholar Linda Dégh put it, "(...) the Orange Maiden (AaTh 408) becomes a princess. She is killed repeatedly by the substitute wife's mother, but returns as a tree, a pot cover, a rosemary, or a dove, from which shape she seven times regains her human shape, as beautiful as she ever was".[19]

- ^ On a related note, Stith Thompson commented that the episode of the heroine bribing the false bride for three nights with her husband occurs in variants of types ATU 425 and ATU 408.[28] In the same vein, scholar Andreas John stated that "the episode of 'buying three nights' in order to recover a spouse is more commonly developed in tales about female heroines who search for their husbands (AT 425, 430, and 432) ..."[29]

- ^ For instance, professor Michael Meraklis commented that despite the general stability of tale type AaTh 403A in Greek variants, the tale sometimes appeared mixed up with tale type AaTh 408, "The Girl in the Citrus Fruit".[30]

- ^ The Georgian Folktale Index registers a similar tale, but with its own indexing: -407*, "The Girl of Reed". In the Georgian type, the hero finds three reeds in the sea, breaks one and releases the maiden. The tale lacks the second part about the maiden's replacement by the false bride.[113]

References[edit]

- ^ Giambattista Basile, Pentamerone, "The Three Citrons" Archived 2014-07-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kawan, Christine Shojaei. "Orangen: Die drei Orangen (AaTh 408)" [Three Oranges (ATU 408)]. In: Enzyklopädie des Märchens Online. Edited by Rolf Wilhelm Brednich, Heidrun Alzheimer, Hermann Bausinger, Wolfgang Brückner, Daniel Drascek, Helge Gerndt, Ines Köhler-Zülch, Klaus Roth and Hans-Jörg Uther. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2016 [2002]. p. 348. https://www-degruyter-com.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/database/EMO/entry/emo.10.063/html. Accessed 2023-05-19.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1961. pp. 135-137.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. pp. 241–243. ISBN 978-951-41-0963-8.

- ^ Steven Swann Jones, The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1995, ISBN 0-8057-0950-9, p. 38.

- ^ Barchilon, Jacques. "Souvenirs et réflexions sur le conte merveilleux". In: Littératures classiques, n°14, janvier 1991. Enfance et littérature au XVIIe siècle. pp. 243-244. doi:10.3406/licla.1991.1282; www.persee.fr/doc/licla_0992-5279_1991_num_14_1_1282

- ^ Kawan, Christine Shojaei. "Orangen: Die drei Orangen (AaTh 408)" [Three Oranges (ATU 408)]. In: Enzyklopädie des Märchens Online, edited by Rolf Wilhelm Brednich, Heidrun Alzheimer, Hermann Bausinger, Wolfgang Brückner, Daniel Drascek, Helge Gerndt, Ines Köhler-Zülch, Klaus Roth and Hans-Jörg Uther. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2016 [2002]. p. 347. https://www-degruyter-com.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/database/EMO/entry/emo.10.063/html. Accessed 2023-06-20.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1961. p. 135.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 241. ISBN 978-951-41-0963-8.

- ^ "Carnation, White, and Black". In: Quiller-Couch, Arthur Thomas. Fairy tales far and near. London, Paris, Melbourne: Cassell and Company, Limited. 1895. pp. 62-74. [1]

- ^ "Red, White and Black". In: Montalba, Anthony Reubens. Fairy tales from all nations. London: Chapman and Hall, 186, Strand. 1849. pp. 243-246.

- ^ "Roth, weiss und schwarz" In: Kletke, Hermann. Märchensaal: Märchen aller völker für jung und alt. Erster Band. Berlin: C. Reimarus. 1845. pp. 181-183.

- ^ Benovska-Sabkova, Milena. ""Тримата братя и златната ябълка" — анализ на митологическата семантика в сравнителен балкански план ["The three brothers and the golden apple": Analysis of the mythological semantic in comparative Balkan aspect]. In: "Българска етнология" [Bulgarian Ethnology] nr. 1 (1995): 100.

- ^ Ranke, Kurt. Folktales of Germany. Routledge & K. Paul. 1966. p. 209. ISBN 9788130400327.

- ^ Mifsud Chircop, Gorg. "Il-hrafa Maltija : 'is-seba' trongiet mewwija' (AT 408)". In: Symposia Melitensia. 2004, Vol. 1. pp. 49-50. ISSN 1812-7509.

- ^ Goldberg, Christine. "The Forgotten Bride (AaTh 313 C)". In: Fabula 33, no. 1-2 (1992): 45. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1992.33.1-2.39

- ^ Goldberg, Christine. [Reviewed Work: The New Comparative Method: Structural and Symbolic Analysis of the Allomotifs of "Snow White" by Steven Swann Jones] In: The Journal of American Folklore 106, no. 419 (1993): 106. Accessed June 14, 2021. doi:10.2307/541351.

- ^ Gulyás Judit (2010). "Henszlmann Imre bírálata Arany János Rózsa és Ibolya című művéről". In: Balogh Balázs (főszerk). Ethno-Lore XXVII. Az MTA Neprajzi Kutatóintezetenek évkönyve. Budapest, MTA Neprajzi Kutatóintezete (Sajtó aatt). pp. 250-253.

- ^ Dégh, Linda. American Folklore and the Mass Media. Indiana University Press. 1994. p. 94. ISBN 0-253-20844-0.

- ^ Goldberg, Christine. "Imagery and Cohesion in the Tale of the Three Oranges (AT 408)". In: Folk-Narrative and World View. Vortage des 10. Kongresses der Internationalen Gesellschaft fur Volkserzahlungsforschung (ISFNR) - Innsbruck 1992. I. Schneider and P. Streng (ed.). Vol. I, 1996. p. 211.

- ^ Shojaei-Kawan, Christine (2004). "Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges (AT 408)". In: Folklore (Electronic Journal of Folklore), XXVII, p. 35.

- ^ Angelopoulos, Anna and Kaplanoglou, Marianthi. "Greek Magic Tales: aspects of research in Folklore Studies and Anthropology". In: FF Network. 2013; Vol. 43. p. 15.

- ^ Vikentiev, V. “Le conte égyptien des deux frères et quelques histoires apparentées: La Fille-Citron — La Fille du Marchand — Gilgamesh — Combabus — Localisation du domaine de Bata à Afka — Yamouneh — Les Cèdres”. In: Bulletin of the Faculty of Arts, Fouad I University, Cairo, 11.2 (December 1949). pp. 67–111.

- ^ نعمت طاووسی, مریم. (1400/2021). 'پریان ایرانی به روایت افسانههای جادویی', مجله مطالعات ایرانی, 20(39), pp. 337-340. doi: 10.22103/jis.2021.15276.1997 (In Iranian)

- ^ Espargham, Samin; Moosavi, S M. "The mythical criticism of the girl of narenj o toranj tale". In: LCQ. 2010; 3: 237-243. URL: http://lcq.modares.ac.ir/article-29-1257-en.html

- ^ Zahra Yazdanpanah; Asieh Qavami, "The Comparative of literary symbols of Naranj o Toranj Myth with Myth of Osiris". In: Comparative Literature Studies 8, no. 29 (2014): 129-151. magiran.com/p1334660 (In Persian)

- ^ Dégh, Linda. Narratives in Society: A Performer-Centered Study of Narration. FF Communications 255. Pieksämäki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 1995. p. 41.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6

- ^ Merakles, Michales G. Studien zum griechischen Märchen. Eingeleitet, übers, und bearb. von Walter Puchner. (Raabser Märchen-Reihe, Bd. 9. Wien: Österr. Museum für Volkskunde, 1992. p. 144. ISBN 3-900359-52-0.