Symphony No. 3 (Brahms)

| Symphony in F major | |

|---|---|

| No. 3 | |

| by Johannes Brahms | |

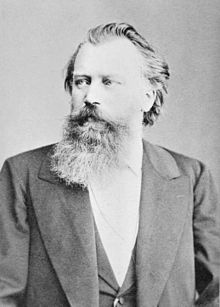

The composer c. 1887 | |

| Opus | 90 |

| Composed | 1883 |

| Duration | ~35 minutes |

| Movements | four |

| Scoring | Orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 2 December 1883 |

| Location | Vienna Musikverein |

| Conductor | Hans Richter |

| Performers | Vienna Philharmonic |

Symphony No. 3 in F major, Op. 90, is a symphony by Johannes Brahms. The work was written in the summer of 1883 at Wiesbaden, nearly six years after he completed his Symphony No. 2. In the interim Brahms had written some of his greatest works, including the Violin Concerto, two overtures (Tragic Overture and Academic Festival Overture), and Piano Concerto No. 2.

The premiere performance was given on 2 December 1883 by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, under the direction of Hans Richter. It is the shortest of Brahms' four symphonies; a typical performance lasts between 35 and 40 minutes.

After each performance, Brahms polished his score further, until it was published in May 1884.

History[edit]

Composition[edit]

By 1877, Johannes Brahms had completed his first two symphonies: The First Symphony in C Minor (Op. 68) was the product of a famously long gestation; its initial drafts dated to as early as 1862. The D Major Second Symphony followed barely 12 months after the First, and the next few years saw Brahms' creative peak, during which he created "a series of large-scale masterpieces with fluency and ease."[1]

Among these masterpieces were Brahms’ Violin Concerto (1878/79) and Second (B♭ major) Piano Concerto (1881), the two symphonic overtures, two large collections of songs (lieder) and duets, several major piano pieces including the third and fourth sets of Hungarian Dances (1879), and three important chamber works, including the ‘lyrical’ and highly popular G major Violin Sonata (1879).[2]

By 1883, Brahms’ attention had returned to the symphony, and he spent the summer of that year at Wiesbaden composing a new F major symphony. In October, he played the first and last movements (on piano) for Antonín Dvořák, who remarked to Nikolaus Simrock: “I say without exaggerating that this work surpasses his first two symphonies; if not, perhaps, in grandeur and powerful conception—then certainly in—beauty.”[3]

"Frei aber froh"[edit]

The first movement begins with a statement (F-A♭-F) which is broadly assumed to represent Brahms' personal motto, frei aber froh (free but happy). Brahms had first developed this motto many years earlier after befriending Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim, who himself had already adopted a personal motto F-A-E, frei aber einsam (free but lonely).

Given Brahms’ reticent nature, there is academic disagreement as to his intent in presenting this motto as a personal musical statement; Brahms himself said nothing on the subject.[3] On the other hand, he often reminded friends that "I speak through my music."[4]

Associations with the Schumanns and the Rhine[edit]

The first movement's opening F-A♭-F motto is followed immediately by a passionato theme; a descending sequence which bears a strong resemblance to a phrase[a] from Robert Schumann's Third Symphony, the 'Rhenish'. Brahms' stay in Wiesbaden (on the Rhine) during the composition of his Third Symphony may also have brought back memories of his early days in Düsseldorf in the home of Robert and Clara Schumann.[3] It was there in 1853 where the young Brahms and Robert Schumann had experimented with 'musical cyphers' for Joachim's amusement.[5]

These associations have led some to refer to the passionato theme as the 'Rhine' theme, but the transition to the second subject includes a chord progression which includes an allusion to the 'Siren's Chorus' from Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser. Whether this reference was a tribute to his recently deceased rival is unknown, although Brahms' admiration of Wagner's music was no secret; he had even possessed the original Tannhäuser manuscript for a time.[3]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in B♭ and A, two bassoons, a contrabassoon, two horns in C, two horns in F, two trumpets in F, three trombones, timpani, and strings.

Although Brahms commonly specified "natural" (valveless) horn tunings in his compositions (e.g., Horn in F), performances are typically delivered on modern valved French horns.

Form[edit]

The symphony consists of four movements, marked as follows:

- Allegro con brio (F major, in sonata form)

- Andante (C major, in a modified sonata form)

- Poco allegretto (C minor, in ternary form A–B–A′)

- Allegro — Un poco sostenuto (F minor → F major, in a modified sonata form)

I. Allegro con brio[edit]

The first movement is in sonata form in 6

4 time. A musical motto of this movement, consisting of three notes, F–A♭–F, was significant to Brahms. In 1853 his friend Joseph Joachim had taken as his motto "Free, but lonely" (in German Frei aber einsam), and from the notes represented by the first letters of these words, F–A–E, Schumann, Brahms and Dietrich had jointly composed a violin sonata dedicated to Joachim. At the time of the Third Symphony, Brahms was a fifty-year-old bachelor who declared himself to be Frei aber froh, "Free but happy". His F–A–F motto, and some altered variations of it, can be heard throughout the symphony.[6] At the beginning of the symphony the motto is the melody of the first three measures, and it is the bass line underlying the main theme in the next three. The motto persists, either boldly or disguised, as the melody or accompaniment throughout the movement.

II. Andante[edit]

The second movement in C major is in modified short sonata form in 4

4 time. The main melody is played by a solo clarinet, which then get passed around to the entire orchestra.

III. Poco allegretto[edit]

The third movement in C minor is a waltz-like ternary movement in 3

8 time. Instead of the rapid scherzo standard in 19th-century symphonies, Brahms created a unique kind of movement that is moderate in tempo (poco allegretto) and intensely lyrical in character.[7]

IV. Allegro — Un poco sostenuto[edit]

The fourth movement is in F minor (ending in F major) and features a modified sonata form in 2

2 time. It is a lyrical, passionate movement, rich in melody that is intensely exploited, altered, and developed. The movement ends with reference to the motto heard in the first movement – one which quotes a motif heard in Schumann's Symphony No. 3, "Rhenish" in the first movement[a] just before the second theme enters in the recapitulation – then fades away to a quiet ending.

Reception[edit]

Hans Richter, who conducted the premiere of the symphony, proclaimed it to be Brahms' Eroica.[8] The symphony was well received, more so than his Second Symphony. Although Richard Wagner had died earlier that year, the public feud between Brahms and Wagner had not yet subsided. Wagner enthusiasts tried to interfere with the symphony's premiere, and the conflict between the two factions nearly brought about a duel.[6]

His friend the influential music critic Eduard Hanslick said, "Many music lovers will prefer the titanic force of the First Symphony; others, the untroubled charm of the Second, but the Third strikes me as being artistically the most nearly perfect."[6]

In popular culture[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ MacDonald 1990, p. 291.

- ^ MacDonald 1990, p. 245-291.

- ^ a b c d Dotsey 2018.

- ^ MacDonald 1990, p. 140.

- ^ MacDonald 1990, p. 304.

- ^ a b c Leonard Burkat; liner notes for the 1998 recording (William Steinberg, conductor; Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra; MCA Classics)

- ^ Kamien, R. (2006). Johannes Brahms. In Music: An appreciation (9th ed., p. 352). McGraw-Hill Humanities.

- ^ MacDonald 1990, p. 302.

References[edit]

- Dotsey, Calvin (30 April 2018). "Secrets of the Rhine: Brahms' Symphony No. 3". Houston Symphony. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- MacDonald, Malcolm (1990). Brahms (1st ed.). Schirmer. ISBN 0-02-871393-1.

- Frisch, Walter (2003). Brahms: The Four Symphonies. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 91–114. ISBN 978-0-300-09965-2.

External links[edit]

- Symphony No. 3: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Detailed Listening Guide using the recording by Claudio Abbado

- European archive Copyright-free LP recording of Brahms 3rd symphony by George Szell (conductor) and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra (for non-American viewers only) at the European Archive.