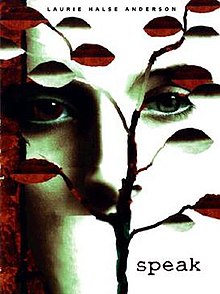

Speak (Anderson novel)

First edition | |

| Author | Laurie Halse Anderson |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Young adult fiction |

| Publisher | Farrar Straus Giroux |

Publication date | October 22, 1999 |

| Media type | Hardback and paperback |

| Pages | 197 pp (first edition, hardback) |

| ISBN | 0-374-37152-0 |

| OCLC | 40298254 |

| [Fic] 21 | |

| LC Class | PZ7.A54385 Sp 1999 |

Speak, published in 1999, is a young adult novel by Laurie Halse Anderson that tells the story of high school freshman Melinda Sordino.[1][2] After Melinda is raped at an end of summer party, she calls the police, who break up the party. Melinda is then ostracized by her peers because she will not say why she called the police.[1][2] Unable to verbalize what happened, Melinda nearly stops speaking altogether,[1] expressing her voice through the art she produces for Mr. Freeman's class.[1][3] This expression slowly helps Melinda acknowledge what happened, face her problems, and recreate her identity.[2][4]

Speak is considered a problem novel, or trauma novel.[1] Melinda's story is written in a diary format, consisting of a nonlinear plot and jumpy narrative that mimics the trauma she experienced.[1][2] Additionally, Anderson employs intertextual symbolism in the narrative, incorporating fairy tale imagery, such as Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter, and author Maya Angelou, to further represent Melinda's trauma.[1]

The novel was based on Anderson's personal experience of having been raped as a teenager and the trauma she faced.[5]

Since its publication, the novel has won several awards and has been translated into sixteen languages.[6] However, the book has faced censorship for its mature content.[7] In 2004, Jessica Sharzer directed the film adaptation, starring Kristen Stewart as Melinda.[8]

Speak: The Graphic Novel, illustrated by Emily Carroll, was published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux February 6, 2018.[9] A 20th anniversary version of the novel featuring additional content was released in 2019 alongside the author's memoir, Shout.[10]

Synopsis[edit]

The summer before her freshman year of high school, Melinda Sordino meets senior Andy Evans at a high school party, who rapes her while she is drunk. Melinda immediately calls 9-1-1, but her shock renders her unable to speak and she flees to go home. The police arrive and break up the party, and several people are arrested. When word spreads that Melinda called the police, she becomes ostracized by her peers and abandoned by her friends.

Melinda is befriended by Heather, a girl from Ohio who is new to the community. However, once Heather realizes that Melinda is an outcast, she abandons her in favor of the "Marthas," a group of girls who seem charitable and outgoing but are actually selfish and cruel. As Melinda's depression worsens, she begins to skip school, withdrawing from her already distant (and somewhat neglectful) parents and other authority figures, who see her reclusiveness as a cry for attention. She slowly befriends her lab partner, David Petrakis, who encourages her to speak up for herself.

Melinda summons the courage to tell her former best friend Rachel, who has been dating Andy, about what happened at the party. While Rachel initially doesn’t believe Melinda, she realizes that this is the truth on prom night after Andy groped her. Enraged at Melinda for exposing him, Andy attacks Melinda in an abandoned janitor's closet. Melinda fights back against Andy, attracting the attention of fellow students. When word spreads about Andy's assaults against Melinda, the students no longer treat her as an outcast, but rather as a hero. Melinda finally regains her voice and tells her story to her art teacher.

Narrative style[edit]

Speak is written for young adults and middle/high school students. Labeled a problem novel, it centers on a character who gains the strength to overcome her trauma.[1][2] The rape troubles Melinda as she struggles with wanting to repress the memory of the event, while simultaneously desiring to speak about it.[2] Knox College English Professor Barbara Tanner-Smith calls Speak a trauma narrative, as the novel allows readers to identify with Melinda's struggles.[1] Hofstra University Writing Studies and Rhetoric Professor Lisa DeTora considers Speak a coming-of-age novel, citing Melinda's "quest to claim a voice and identity".[3] Booklist calls Speak an empowerment novel.[11] According to author Chris McGee, Melinda is more than a victim.[2] Melinda gains power from being silent as much as speaking.[2] McGee considers Speak a confessional narrative; adults in Melinda's life constantly demand a "confession" from her.[2] Similarly, author and Florida State University Professor Don Latham sees Speak as a "coming-out" story.[4] He claims that Melinda uses both a literal and metaphorical closet to conceal and to cope with having been raped.[4]

Theme[edit]

One theme of Speak is finding one's voice.[2] Another theme in the novel is identity.[4] The story can also be viewed as speaking out against violence and victimization.[12] Melinda feels guilty, even though she was a victim of sexual assault. Yet, by seeing other victims, like Rachel, Melinda is able to speak.[12] Some see Speak as a story of recovery.[1][4] According to Latham, writing/narrating her story has a therapeutic effect on Melinda, allowing her to "recreate" herself.[4]

Post traumatic stress disorder[edit]

One interpretation of Melinda's behavior is that it is symptomatic of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of her rape.[1][4] Like other trauma survivors, Melinda's desire to both deny and proclaim what happened produces symptoms that both attract and deflect attention.[4] Don Latham and Lisa DeTora both define Melinda's PTSD within the context of Judith Herman's three categories of classic PTSD symptoms: "hyperarousal", "intrusion", and "constriction".[3][4] Melinda displays hyperarousal in her wariness of potential danger.[3][4] Melinda will not go over to David's house after the basketball game, because she is afraid of what might happen.[3][4] Intrusion is depicted in the rape's disruption of Melinda's consciousness.[4] She tries to forget the event, but the memories keep resurfacing in her mind.[4] Constriction is illustrated in Melinda's silence and withdrawal from society.[4] Latham views Melinda's slow recovery as queer in its diversion from the normal treatment of trauma.[4] Melinda's recovery comes as a result of her own efforts, without professional help.[4] Further, DeTora notes the connection between trauma and "the unspeakable".[3]

Point of view[edit]

Speak is a first-person, diary-like narrative. Written in the voice of Melinda Sordino, it features lists, subheadings, spaces between paragraphs and script-like dialogue. The fragmented style mimics Melinda's trauma.[1][2] The choppy sentences and blank spaces on the pages relate to Melinda's fascination with Cubism.[2] According to Chris McGee and DeTora, Anderson's writing style allows the reader to see how Melinda struggles with "producing the standard, cohesive narrative" expected in a teen novel.[2][3] Melinda's distracted narrative reiterates the idea that "no one really wants to hear what you have to say".[2] In her article, "Like Falling Up into a Storybook", Barbara Tannert-Smith says,

"In Speak, Anderson of necessity has to employ a nonlinear plot and disruptive temporality to emphasize Melinda's response to her traumatic experience: the novelist has to convey stylistically exactly how her protagonist experiences self-estrangement and a sense of shattered identity".[1]

By disrupting the present with flashbacks of the past, Anderson further illustrates the structure of trauma.[1] Anderson organizes the plot around the four quarters of Melinda's freshman year, starting the story in the middle of Melinda's struggle.[3] Anderson superimposed the fragmented trauma plot-line upon this linear high school narrative, making the narrative more believable.[3]

Symbolism and greater meaning[edit]

Throughout Speak, Anderson represents Melinda's trauma and recovery symbolically.[1] Barbara Tannert-Smith refers to Speak as a "postmodern revisionary fairy tale" for its use of fairy tale imagery.[1] She sees Merryweather High School as the "ideal fairy tale domain", featuring easily categorized characters—a witchy mother, a shape-shifting best friend, a beastly rapist.[1] Mirrors, traditional fairy tale tools, signify Melinda's struggle with her shattered identity.[1][4] After being raped, Melinda does not recognize herself in her reflection. Disgusted by what she sees, Melinda avoids mirrors. According to Don Latham, Melinda's aversion to her reflection illustrates acknowledgement of her fragmented identity.[4] In fact, the only mirror Melinda can "see herself" in, is the three-way mirror in the dressing room.[1][4] Rather than giving the illusion of a unified self, the three-way mirror reflects Melinda's shattered self.[1][4] Likewise, Melinda is fascinated by Cubism, because it represents what is beyond the surface.[1][4] Melinda uses art to express her voice. Her post-traumatic artwork illustrates her pain.[1] The trees symbolize Melinda's growth.[1] The walls of Melinda's closet are covered in her tree sketches, creating a metaphorical forest in which she hides from reliving her trauma.[1] According to Don Latham, the closets in the story symbolize Melinda's queer coping strategies.[4] Melinda uses the closet to conceal the truth.[4]

Anderson incorporates precursor texts that parallel Melinda's experience.[1] In the story, Melinda's English class studies Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter, which features similar fairy tale imagery.[1] Hester Prynne, an outcast protagonist like Melinda, lives in a cottage at the edge of the woods. Hester's cottage parallels Melinda's closet.[1] For both women, the seclusion of the forest represents a space beyond social demands.[1] The deciphering of Hawthorne's symbolism mimics the process faced by readers of Melinda's narrative.[1] Similarly, Anderson connects Melinda's trauma to that of Maya Angelou, author of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Melinda places a poster of Angelou in her closet. She admires Angelou because her novel was banned by the school board. Melinda and Angelou were both outcasts.[1] Like Melinda, Angelou was silenced following her childhood rape.[4]

Honors and accolades[edit]

Speak is a New York Times Best-Seller.[13][14] The novel received several awards and honors, including the American Library Association's 2000 Michael Printz Honor[15] and the 2000 Golden Kite Award. It was also selected as a 2000 ALA Best Book For Young Adults.[16][17] Speak gained critical acclaim for its portrayal of the trauma caused by rape.[18] Barbara Tannert-Smith, author of "Like Falling Up Into a Storybook: Trauma and Intertextual Repetition in Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak.", claims the story's ability to speak the reader's language brought about its commercial success.[1] Publishers Weekly says, Speak's "overall gritty realism and Melinda's hard-won metamorphosis will leave readers touched and inspired".[19] Ned Vizzini, for the New York Times, calls it "different", "a grittily realistic portrait of sexual violence in high school."[20] Author Don Latham calls Speak "painful, smart, and darkly comic".[4]

Awards[edit]

Speak has won several awards and honors, including:

- 1999 National Book Award Finalist[21]

- 1999 BCCB Blue Ribbon Book[22]

- 2000 SCBWI Golden Kite Award for Fiction[16]

- 2000 Horn Book Fanfare Best Book of the Year[23]

- 2000 ALA Best Books for Young Adults[17]

- 2000 Printz Honor Book[24]

- 2000 Top Ten Best Books for Young Adults[25]

- 2000 Fiction Quick Pick for Reluctant Young Adult Readers[26]

- 2000 Edgar Allan Poe Best Young Adult Award Finalist[27]

- 2001 New York Times Paperback Children's Best Seller[13]

- 2005 New York Times Paperback Children's Best Seller[14]

Censorship[edit]

Speak's difficult subject matter has led to censorship of the novel.[7] Speak is ranked 60th on the ALA's list of Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books for 2000–2009[28] and 25th for 2010–2019.[29] In 2020, the book was named the fourth most banned and challenged book in the United States "because it was thought to contain a political viewpoint and it was claimed to be biased against male students, and for the novel’s inclusion of rape and profanity."[30]

In September 2010, Wesley Scroggins, a professor at Missouri State University, wrote an article, "Filthy books demeaning to Republic education", in which he claimed that Speak, along with Slaughterhouse Five and Twenty Boy Summer, should be banned for "exposing children to immorality".[31] Scroggins claimed that Speak should be "classified as soft pornography" and, therefore, removed from high school English curriculum.[31] In its 2010-2011 bibliography, "Books Challenged or Banned", the Newsletter of Intellectual Freedom lists Speak as having been challenged in Missouri schools because of its "soft-pornography" and "glorification of drinking, cursing, and premarital sex."[32]

In the 2006 Platinum Edition of Speak, and on her blog, Laurie Halse Anderson spoke out against censorship. Anderson wrote:

...But censoring books that deal with difficult, adolescent issues does not protect anybody. Quite the opposite. It leaves kids in the darkness and makes them vulnerable. Censorship is the child of fear and the father of ignorance. Our children cannot afford to have the truth of the world withheld from them.[33]

In her scholarly monograph, Laurie Halse Anderson: Speaking in Tongues, Wendy J. Glenn claims that Speak "has generated more academic response than any other novel Anderson has written."[34] Despite hesitancy to teach a novel with "mature subject matter," English teachers are implementing Speak in the classroom as a study of literary analysis, as well as tool to teach students about sexual harassment.[35] The novel gives students the opportunity to talk about several teen issues, including: school cliques, sex, and parental relationships.[35] Of teaching Speak in the classroom Jackett says, "We have the opportunity as English teachers to have an enormously positive impact on students' lives. Having the courage to discuss the issues found in Speak is one way to do just that."[35] By sharing in Melinda's struggles, students may find their own voices and learn to cope with trauma and hardships.[36] According to Janet Alsup, teaching Speak in the classroom, can help students become more critically literate.[36] Students may not feel comfortable talking about their own experiences, but they are willing to talk about what happens to Melinda.[36] Elaine O'Quinn claims that books like Speak allow students to explore inner dialogue.[37] Speak provides an outlet for students to think critically about their world.[36]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Tannert-Smith, Barbara (Winter 2010). "'Like Falling up into a Storybook': Trauma and Intertextual Repetition in Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 35 (4): 395–414. doi:10.1353/chq.2010.0018. S2CID 145074033.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n McGee, Chris (Summer 2009). "Why Won't Melinda Just Talk about What Happened? Speak and the Confessional Voice". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 34 (2): 172–187. doi:10.1353/chq.0.1909. S2CID 144567845.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Detora, Lisa (Summer 2006). "Coming of Age in Suburbia". Modern Language Studies. 36 (1): 24–35. doi:10.2307/27647879. JSTOR 27647879.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Latham, Don (Winter 2006). "Melinda's Closet: Trauma and the Queer Subtext of Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 31 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1353/chq.2007.0006. S2CID 143591006.

- ^ Anderson, Laurie (2018). Speak: The Graphic Novel. Macmillan. ISBN 9780374300289.

- ^ Glenn, Wendy (2010). Laurie Halse Anderson: Speaking in Tongues. USA: Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8108-7282-0.

- ^ a b Glenn, Wendy (2010). Laurie Halse Anderson: Speaking in Tongues. Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8108-7282-0.

- ^ Andrea LeVasseur (2007). "Speak (2003)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Laurie Halse (2018-02-06). Speak: The Graphic Novel. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR). ISBN 978-1-4668-9787-8.

- ^ "Speak: 20th Anniversary Edition". madwomanintheforest.com. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- ^ Carton, Debbie. Booklist Review. Booklist Online. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ a b Franzak, Judith; Elizabeth Noll (May 2006). "Monstrous Acts: Problematizing Violence in Young Adult Literature". Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 49 (8): 667–668. doi:10.1598/jaal.49.8.3. JSTOR 40014090.

- ^ a b "Children's Best Sellers". New York Times. July 8, 2001. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Children's Best Sellers". New York Times. Sep 11, 2005. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Michael L. Printz Winners and Honor Books". Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA). 2007-03-15. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- ^ a b "Golden Kite Awards Recipients". Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Best Books for Young Adults". Young Adult Library Services Association. 29 September 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2012. Manczuk, Suzanne; etc., Tennessee Volunteer State Book Award Young Adults 2012

- ^ Burns, Tom, ed. (2008). "Laurie Halse Anderson". Children's Literature Review. 138. Gale, Cengage Learning: 1–24. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "Children's Book Review: Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson, Author Farrar Straus Giroux $17 (198p) ISBN 978-0-374-37152-4".

- ^ Vizzini, Ned (Nov 5, 2010). "Angels, Demons and Blockbusters". New York Times. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "National Book Awards - 1999". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "1999 Blue Ribbons". The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Horn Book Fanfare". The Horn Book Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ Bradburn, Frances; etc. "2000 Printz Award". Young Adult Library Services Association. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Manczuk, Suzanne; etc. (29 September 2006). "2000 Top Ten Best Books for Young Adults". Young Adult Library Services Association. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Long, Mary; etc. (29 September 2006). "Quick Picks for Reluctant Young Adult Readers". Young Adult Library Services Association. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Edgars Database". Mystery Writers of America. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books 2000-2009". American Library Association. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Banned & Challenged Books (2020-09-09). "Top 100 Most Banned and Challenged Books: 2010-2019". Office for Intellectual Freedom. American Library Association. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Banned & Challenged Books (2013-03-26). "Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists". Office for Intellectual Freedom. American Library Association. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ a b Scroggins, Wesley (Sep 17, 2010). "Filthy books demeaning to republic education". News-Leader. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Doyle, Robert (2011). "Books Challenged or Banned in 2010-2011" (PDF). Newsletter of Intellectual Freedom: 4. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Anderson, Laurie Halse (1999). Speak. United States: Farrar Straus Giroux. ISBN 0-14-240732-1.

- ^ Glenn, Wendy (2010). Laurie Halse Anderson: Speaking in Tongues. Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8108-7282-0.

- ^ a b c Jackett, Mark (March 2007). "Something to Speak About: Addressing Sensitive Issues Through Literature". English Journal. 96 (4): 102–105. doi:10.2307/30047174. JSTOR 30047174.

- ^ a b c d Alsup, Janet (October 2003). "Politicizing Young Adult Literature: Reading Anderson's Speak as a Critical Text". Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 47 (2): 158–166. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ O'Quinn, Elaine (Fall 2001). "Between Voice And Voicelessness:Transacting Silence in Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak". The ALAN Review. 29 (1): 54–58. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

External links[edit]

- 1999 American novels

- Novels by Laurie Halse Anderson

- American young adult novels

- Novels about rape

- Novels about bullying

- Obscenity controversies in literature

- American novels adapted into films

- Golden Kite Award-winning works

- Novels set in high schools and secondary schools

- Fiction about proms

- Novels about post-traumatic stress disorder

- Novels about violence against women

- Nonlinear narrative novels

- Epistolary novels

- Farrar, Straus and Giroux books