Siege of Trsat

| Siege of Trsat | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Frankish campaign against Avars and Slavs | |||||||

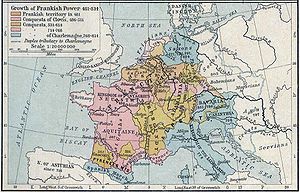

Map showing growth of Frankish power from 481–814. Location of the battle was near the Frankish–Croatian border | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Croats[1][2][3] Citizens of Tarsatica[4] | Franks[1] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Višeslav of Croatia[6] | Eric of Friuli †[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown—heavy[6] | ||||||

Location of the siege within modern Croatia | |||||||

The siege of Trsat (Croatian: Opsada Trsata) was a battle fought over possession of the town of Trsat (Latin: Tarsatica)[Note 1] in Liburnia, near the Croatian–Frankish border.[1] The battle was fought in the autumn of 799 between the defending forces of Dalmatian Croatia under the leadership of Croatian duke Višeslav, and the invading Frankish army of the Carolingian Empire led by Eric of Friuli.[6] The battle was a Croatian victory, and the Frankish commander Eric was killed during the siege.[5][2][7]

The Frankish invasion of Croatia, the destruction of Tarsatica, the coronation of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor, and negotiations from 802–815 between the Franks and Byzantines led to a stalemate. Dalmatian Croatia consequently peacefully accepted a limited Frankish overlordship.[4]

Background[edit]

Charlemagne, King of the Franks from 768 until his death in 814, expanded the Frankish kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of western and central Europe.[8] He brought the Frankish state face to face with the Slavs to the northeast and the Avars and Slavs to the southeast of the Frankish Empire.[8] The Croats lived in Principality of Lower Pannonia and Dalmatian Croatia (Littoral Croatia) to the southeast of the Frankish Empire. Dalmatian Croatia was ruled by Duke Višeslav, one of the first known Croatian dukes.[9]

While fighting the Avars, the Franks called for Slavic-Croatian support.[5] Croatian Prince Vojnomir launched a joint counterattack with the help of Frankish troops under Charlemagne in 791.[10] The offensive was successful and the Avars were driven out of Croatia.[10] In return for the help of Charlemagne, Vojnomir was obliged to recognize Frankish sovereignty, convert to Christianity, and have his territory named Principality of Lower Pannonia.[10] Charlemagne again campaigned against the Avars and won a major victory in 796.[11] Prince Vojnomir aided him, and the Franks became overlords of the Croatians of northern Dalmatia, Slavonia, and Pannonia.[11] The Franks placed Pannonian Croats under Eric, the margrave of Friuli, who then tried to extend his rule over the Croatians of Dalmatia.[12]

The conquest of Istria by the Franks brought the realm of Charlemagne adjacent to Dalmatia.[13] Dalmatia at that time included both Roman cities and a Slavic-Croatian hinterland that was loosely subject to the rule of the Byzantine Empire.[13] In the treaty of 798, the Franks acknowledged Byzantine rights over the Slavs, but in the following years both Croatian Župans (dukes) and Roman communities recognized an opportunity to win full independence from both Imperial powers.[13]

As the eldest son of Gerold of Anglachgau and as a high ranking Frankish commander, Eric was titled from 789 to his death the Duke of Friuli (dux Foroiulensis). He was appointed governor of Istria, Friuli, and neighbouring areas by Charlemagne. Eric wanted to extend his dominion by conquering Dalmatian Croatia.[Note 2][1][12][14] In the autumn of 799, Eric marched from Istria along the seacoast of Liburnia towards the town of Trsat, which is today part of the city of Rijeka.[14] Meanwhile his opponent, Duke Višeslav, gathered his forces and moved north from his governing center at Nin.[6]

Siege[edit]

Upon arriving at the foot of the settlement, Eric besieged and attacked the city, but was repelled. Led by Duke Višeslav, the inhabitants of Trsat threw spears, shot arrows, and hurled huge stones on the enemy, and managed to kill many of them.[Note 3][14] Eric's forces fled their positions, and were subsequently routed by the forces of Višeslav in an ambush.[15] Eric was among those killed, and his death and defeat proved to be a great blow for the Carolingian Empire.[8][14][16] Aquileian Patriarch Saint Paulinus II cursed the land in which the hero was killed, and wrote Carmen de regula fidei, the rhythmus or elegy for his death.[14]

According to contemporary Frankish scholar and courtier Einhard, Eric was killed at Trsat (Tarsatch), a town on the coast of Liburnia, by the treachery of the inhabitants.[16] Due to a lack of primary materials, it is uncertain who killed Duke Eric. Most of historians point at Croats,[3] while some point at Byzantines.[17] Einhard also notes the death of Gerold, Prefect of Bavaria, another Frankish commander who was slain in Pannonia in the same year.[16] Croatian historian Nenad Labus refers to this event as a successful assassination attempt by Avars and Slavs.[17] Historian Pierre Riché believes that Dalmatian Croats (Guduscani) killed Eric in collusion with Avars.[3]

Besides the Royal Frankish Annals (Annales Regni Francorum), there is another primary source compiled in c. 950, the historical work De administrando imperio, ascribed to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, which refers to Croatian-Frankish relations.[18] Constantine notes that for a number of years the Croats of Dalmatia were subjects of the Franks, who treated them brutally.[18] The Croats revolted and slew their princes.[18] In an act of revenge, a large army from Francia invaded Croatia.[18] After seven years of war, the Croats managed to defeat the Franks, killing a large portion of the invading army along with its commander.[18] Although Constantine describes a chain of events that are analogous to the siege of Trsat, he does not mention Tarsatica or the exact year of these events.[18]

Aftermath[edit]

In 800, Eric's successor Cadolah of Friuli invaded Dalmatian Croatia by the order of Charlemagne, but without considerable military success.[14] Still, Tarsatica was burned down.[Note 4][14] Tarsatica's surviving inhabitants moved to a more protected hill, where they established a new settlement called Trsat.[Note 5] Višeslav continued to rule over Dalmatian Croatia and warred against the Franks, avoiding defeat upon his death in 802.[14] He was succeeded by his son Borna, who later become a Frankish ally.[14][19]

On Christmas Day in 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Imperator Romanorum (Holy Roman Emperor) in Saint Peter's Basilica.[12][14] This was a direct challenge to Byzantium's claim to be the one—the Roman—empire.[12] Nicephorus I of the Byzantine Empire and Charlemagne of the Holy Roman Empire settled their imperial boundaries in 803. Dalmatian Croatia peacefully accepted a limited Frankish overlordship.[14] The peace of Aache in 812 confirmed Dalmatia, except for the Byzantine cities and islands, as under Frankish domain.[4]

Ljudevit Posavski, Croatian Duke of Pannonian Croatia, led a resistance to Frankish domination.[20][21] Ljudevit also had to fight against Dalmatian Croatia, as their prince Borna was a Frankish ally.[19] After unsuccessful resistance by Ljudevit and Pannonian Croats, the Franks again controlled Istria, Dalmatia, and Pannonia.[22] Nevertheless, Dalmatian Croatia remained a semi-independent duchy between the two Empires, as they had a right to elect their own prince.[22]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The city of Tarsatica, where the siege happened, was probably located at the present Old Town in Rijeka, not at Trsat itself, which is found on a hill overlooking Rijeka on the other side of the Rječina River. Trsat was actually founded by the Tarsatica's surviving inhabitants, a year after the siege. (Croatian Academy of America. Journal of Croatian studies (1986), Vol. 27–30)

- ^ According to Denis Sinor, it is possible that Eric set his army to fight the Avars and was attacked by Croats at Trsat. (Sinor (1990), p. 219.)

- ^ This description of the battle can also be found in primary material from Aquileian Patriarch Saint Paulinus II. In his poem "Versus de Herico duce" he mention throwing spears, arrows, and huge stones upon Eric.

- ^ Historians have a disagreement whether Tarsatica was destroyed in 799 or in 800.

- ^ According to Ferdo Šišić, Rijeka was founded by the Croats after the destruction of Tarsatica. (Šišić, Ferdo. Abridged Political History of Rieka (Fiume) (1919))

References[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Scholz 1970, p. 191

- ^ a b Rogers 2002, p. 77

- ^ a b c Riché 1993, p. 111

- ^ a b c Dzino 2010, p. 183

- ^ a b c Sinor 1990, p. 219

- ^ a b c d e Gaži 1973, p. 20

- ^ Žic 2001, p. 18

- ^ a b c Ross 1945, pp. 212–235

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 296

- ^ a b c Dvornik 1959, p. 69

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 257

- ^ a b c d Fine 1991, p. 252

- ^ a b c Bury 2008, p. 329

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Klaić 1985, pp. 63–64

- ^ Tomac 1959, p. 304

- ^ a b c Einhard, Vita Karoli Magni

- ^ a b Labus 2000, pp. 1–16

- ^ a b c d e f Constantine Porphyrogenitus, pp. 143–145

- ^ a b Scholz 1970, p. 106

- ^ Riché 1993, pp. 158–159

- ^ Royal Frankish Annales Annales Regni Francorum ed. G. H. Pertz. Monumenta Germanicae Historica, Scriptores rerum Germanicarum 6, (Hannover 1895) for the years 819–822.

- ^ a b Scholz 1970, p. 197

Bibliography[edit]

- Bury, John Bagnell (2008). History of the Eastern Empire from the Fall of Irene to the Accession of Basil: A.D. 802-867, Dij. 802-867. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9789536531318.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus (1967). Moravcsik, Gy. (ed.). De Administrando Imperio. Translated by R.J.H. Jenkins (Rev. ed.). Washington: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 9780884020219.

- Dvornik, Francis (1959). The Slavs: their early history and civilization. American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- Dzino, Danijel (2010). Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia. Brill. ISBN 9789004186460.

- Einhard (1880). Turner, Samuel Epes (ed.). The Life of Charlemagne (Vita Karoli Magni). Translated by Samuel Epes Turner. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The early medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Gaži, Stephen (1973). A history of Croatia. Philosophical Library. ISBN 9780802221087.

- Klaić, Vjekoslav (1985). Povijest Hrvata: Knjiga Prva (in Croatian). Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske. ISBN 9788640100519.

- Labus, Nenad (2000). "Tko je ubio vojvodu Erika" [Who was Duke Eric?] (PDF). Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru (in Croatian). 42. Zagreb: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts: 1–16. ISSN 1330-0474.

- Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: a family who forged Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812213423.

- Rogers, Clifford J. (2002). The journal of medieval military history. New York: Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851159096.

- Ross, James Bruce (April 1945). "Two Neglected Paladins of Charlemagne: Erich of Friuli and Gerold of Bavaria". Speculum. 20 (2). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Medieval Academy of America: 212–235. doi:10.2307/2854596. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2854596. S2CID 163300685.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter (1970). Carolingian chronicles: Royal Frankish annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472061860.

- Sinor, Denis (1990). The Cambridge history of early Inner Asia. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24304-1.

- Tomac, Petar (1959). Vojna istorija (in Croatian). Belgrade: Vojnoizdavački zavod JNA. LCCN 60039538. OCLC 21319446.

- Žic, Igor (2001). Kratka povijest grada Rijeke (in Croatian). Adamić. ISBN 9789536531318.

External links[edit]

- (in Croatian) Map of Littoral Croatian Duchy in early 9th century