Poverty threshold

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2019) |

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line, or breadline[1] is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country.[2] The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for the average adult.[3] The cost of housing, such as the rent for an apartment, usually makes up the largest proportion of this estimate, so economists track the real estate market and other housing cost indicators as a major influence on the poverty line.[4] Individual factors are often used to account for various circumstances, such as whether one is a parent, elderly, a child, married, etc. The poverty threshold may be adjusted annually. In practice, like the definition of poverty, the official or common understanding of the poverty line is significantly higher in developed countries than in developing countries.[5][6]

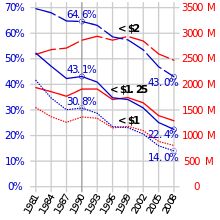

In September 2022, the World Bank updated the International Poverty Line (IPL), a global absolute minimum, to $2.15 per day[7] (in PPP). In addition, as of 2022, $3.65 per day in PPP for lower-middle income countries, and $6.85 per day in PPP for upper-middle income countries.[8][9] Per the $1.90/day standard, the percentage of the global population living in absolute poverty fell from over 80% in 1800 to 10% by 2015, according to United Nations estimates, which found roughly 734 million people remained in absolute poverty.[10][11]

History[edit]

Charles Booth, a pioneering investigator of poverty in London at the turn of the 20th century, popularised the idea of a poverty line, a concept originally conceived by the London School Board.[12] Booth set the line at 10 (50p) to 20 shillings (£1) per week, which he considered to be the minimum amount necessary for a family of four or five people to subsist on.[13] Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree (1871–1954), a British sociological researcher, social reformer and industrialist, surveyed rich families in York, and drew a poverty line in terms of a minimum weekly sum of money "necessary to enable families … to secure the necessaries of a healthy life", which included fuel and light, rent, food, clothing, and household and personal items. Based on data from leading nutritionists of the period, he calculated the cheapest price for the minimum calorific intake and nutritional balance necessary, before people get ill or lose weight. He considered this amount to set his poverty line and concluded that 27.84% of the total population of York lived below this poverty line.[14] This result corresponded with that from Booth's study of poverty in London and so challenged the view, commonly held at the time, that abject poverty was a problem particular to London and was not widespread in the rest of Britain. Rowntree distinguished between primary poverty, those lacking in income and secondary poverty, those who had enough income, but spent it elsewhere (1901:295–96).[14]

The poverty threshold was first developed by Mollie Orshansky between 1963 and 1964. She attributed the poverty threshold as a measure of income inadequacy by taking the cost of food plan per family of three or four and multiplying it by a factor of three. In 1969 the inter agency poverty level review committee adjusted the threshold for only price changes.[15]

Absolute poverty and the International Poverty Line[edit]

The term "absolute poverty" is also sometimes used as a synonym for extreme poverty. Absolute poverty is the absence of enough resources to secure basic life necessities.

To assist in measuring this, the World Bank has a daily per capita international poverty line (IPL), a global absolute minimum, of $2.15 a day as of September 2022.[17]

The new IPL replaces the $1.25 per day figure, which used 2005 data.[18] In 2008, the World Bank came out with a figure (revised largely due to inflation) of $1.25 a day at 2005 purchasing power parity (PPP).[19] The new figure of $1.90 is based on ICP PPP calculations and represents the international equivalent of what $1.90 could buy in the US in 2011. Most scholars agree that it better reflects today's reality, particularly new price levels in developing countries.[20] The common IPL has in the past been roughly $1 a day.[21]

These figures are artificially low according to Peter Edward of Newcastle University. He believes the real number as of 2015 was $7.40 per day.[22]

Using a single monetary poverty threshold is problematic when applied worldwide, due to the difficulty of comparing prices between countries. [citation needed] Prices of the same goods vary dramatically from country to country; while this is typically corrected for by using PPP exchange rates, the basket of goods used to determine such rates is usually unrepresentative of the poor, most of whose expenditure is on basic foodstuffs rather than the relatively luxurious items (washing machines, air travel, healthcare) often included in PPP baskets. The economist Robert C. Allen has attempted to solve this by using standardized baskets of goods typical of those bought by the poor across countries and historical time, for example including a fixed calorific quantity of the cheapest local grain (such as corn, rice, or oats).[23]

Basic needs[edit]

The basic needs approach is one of the major approaches to the measurement of poverty in developing countries. It attempts to define the absolute minimum resources necessary for long-term physical well-being, usually in terms of consumption goods. The poverty line is then defined as the amount of income required to satisfy those needs. The 'basic needs' approach was introduced by the International Labour Organization's World Employment Conference in 1976.[24][25] "Perhaps the high point of the WEP was the World Employment Conference of 1976, which proposed the satisfaction of basic human needs as the overriding objective of national and international development policy. The basic needs approach to development was endorsed by governments and workers' and employers' organizations from all over the world. It influenced the programs and policies of major multilateral and bilateral development agencies, and was the precursor to the human development approach."[24][25]

A traditional list of immediate "basic needs" is food (including water), shelter, and clothing.[26] Many modern lists emphasize the minimum level of consumption of 'basic needs' of not just food, water, and shelter, but also sanitation, education, and health care. Different agencies use different lists. According to a UN declaration that resulted from the World Summit on Social Development in Copenhagen in 1995, absolute poverty is "a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education, and information. It depends not only on income, but also on access to services."[27]

David Gordon's paper, "Indicators of Poverty and Hunger", for the United Nations, further defines absolute poverty as the absence of any two of the following eight basic needs:[27]

- Food: Body mass index must be above 16.

- Safe drinking water: Water must not come solely from rivers and ponds, and must be available nearby (fewer than 15 minutes' walk each way).

- Sanitation facilities: Toilets or latrines must be accessible in or near the home.

- Health: Treatment must be received for serious illnesses and pregnancy.

- Shelter: Homes must have fewer than four people living in each room. Floors must not be made of soil, mud, or clay.

- Education: Everyone must attend school or otherwise learn to read.

- Information: Everyone must have access to newspapers, radios, televisions, computers, or telephones at home.

- Access to services: This item is undefined by Gordon, but normally is used to indicate the complete panoply of education, health, legal, social, and financial (credit) services.

In 1978, Ghai investigated the literature that criticized the basic needs approach. Critics argued that the basic needs approach lacked scientific rigour; it was consumption-oriented and antigrowth. Some considered it to be "a recipe for perpetuating economic backwardness" and for giving the impression "that poverty elimination is all too easy".[28] Amartya Sen focused on 'capabilities' rather than consumption.

In the development discourse, the basic needs model focuses on the measurement of what is believed to be an eradicable level of poverty.

Relative poverty[edit]

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Relative poverty. (Discuss) (September 2020) |

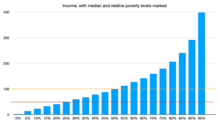

Relative poverty means low income relative to others in a country:[29] for example, below 60% of the median income of people in that country.

Relative poverty measurements unlike absolute poverty measurements take the social economic environment of the people observed into consideration. It is based on the assumption that whether a person is considered poor depends on her/his income share relative to the income shares of other people who are living in the same economy.[29] The threshold for relative poverty is considered to be at 50% of a country's median equivalised disposable income after social transfers. Thus, it can vary greatly from country to country even after adjusting for purchasing power standards (PPS).[30]

A person can be poor in relative terms but not in absolute terms as the person might be able to meet her/his basic needs, but not be able to enjoy the same standards of living that other people in the same economy are enjoying.[31] Relative poverty is thus a form of social exclusion that can for example affect peoples access to decent housing, education or job opportunities.[31]

The relative poverty measure is used by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Canadian poverty researchers.[32][33][34][35][36] In the European Union, the "relative poverty measure is the most prominent and most–quoted of the EU social inclusion indicators."[37]

"Relative poverty reflects better the cost of social inclusion and equality of opportunity in a specific time and space."[38]

"Once economic development has progressed beyond a certain minimum level, the rub of the poverty problem – from the point of view of both the poor individual and of the societies in which they live – is not so much the effects of poverty in any absolute form but the effects of the contrast, daily perceived, between the lives of the poor and the lives of those around them. For practical purposes, the problem of poverty in the industrialized nations today is a problem of relative poverty (page 9)."[38][39]

However, some [who?] have argued that as relative poverty is merely a measure of inequality, using the term 'poverty' for it is misleading. For example, if everyone in a country's income doubled, it would not reduce the amount of 'relative poverty' at all.

History of the concept of relative poverty[edit]

In 1776, Adam Smith argued that poverty is the inability to afford "not only the commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life, but whatever the custom of the country renders it indecent for creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without."[40][41]

In 1958, John Kenneth Galbraith argued, "People are poverty stricken when their income, even if adequate for survival, falls markedly behind that of their community."[41][42]

In 1964, in a joint committee economic President's report in the United States, Republicans endorsed the concept of relative poverty: "No objective definition of poverty exists. ... The definition varies from place to place and time to time. In America as our standard of living rises, so does our idea of what is substandard."[41][43]

In 1965, Rose Friedman argued for the use of relative poverty claiming that the definition of poverty changes with general living standards. Those labelled as poor in 1995, would have had "a higher standard of living than many labelled not poor" in 1965.[41][44]

In 1967, American economist Victor Fuchs proposed that "we define as poor any family whose income is less than one-half the median family income."[45] This was the first introduction of the relative poverty rate as typically computed today[46][47]

In 1979, British sociologist, Peter Townsend published his famous definition: "individuals... can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and amenities which are customary, or are at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong (page 31)."[48]

Brian Nolan and Christopher T. Whelan of the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) in Ireland explained that "poverty has to be seen in terms of the standard of living of the society in question."[49]

Relative poverty measures are used as official poverty rates by the European Union, UNICEF and the OECD. The main poverty line used in the OECD and the European Union is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 60% of the median household income.[50]

Relative poverty compared with other standards[edit]

A measure of relative poverty defines "poverty" as being below some relative poverty threshold. For example, the statement that "those individuals who are employed and whose household equivalised disposable income is below 60% of national median equivalised income are poor" uses a relative measure to define poverty.[51]

The term relative poverty can also be used in a different sense to mean "moderate poverty" – for example, a standard of living or level of income that is high enough to satisfy basic needs (like water, food, clothing, housing, and basic health care), but still significantly lower than that of the majority of the population under consideration. An example of this could be a person living in poor conditions or squalid housing in a high crime area of a developed country and struggling to pay their bills every month due to low wages, debt or unemployment. While this person still benefits from the infrastructure of the developed country, they still endure a less than ideal lifestyle compared to their more affluent countrymen or even the more affluent individuals in less developed countries who have lower living costs.[52]

Living Income Concept[edit]

Living Income refers to the income needed to afford a decent standard of living in the place one lives. The distinguishing feature between a living income and the poverty line is the concept of decency, wherein people thrive, not only survive. Based on years of stakeholder dialogue and expert consultations, the Living Income Community of Practice, an open learning community, established the formal definition of living income drawing on the work of Richard and Martha Anker, who co-authored "Living Wages Around the World: Manual for Measurement". They define a living income as:[53]

The net annual income required for a household in a particular place to afford a decent standard of living for all members of that household. Elements of a decent standard of living include food, water, housing, education, healthcare, transport, clothing, and other essential needs including provision for unexpected events.

Like the poverty line calculation, using a single global monetary calculation for Living Income is problematic when applied worldwide.[54] Additionally, the Living Income should be adjusted quarterly due to inflation and other significant changes such as currency adjustments.[53] The actual income or proxy income can be used when measuring the gap between initial income and the living income benchmarks. The World Bank notes that poverty and standard of living can be measured by social perception as well, and found that in 2015, roughly one-third of the world's population was considered poor in relation to their particular society.[55]

The Living Income Community of Practice (LICOP) was founded by The Sustainable Food Lab, GIZ and ISEAL Alliance to measure the gap between what people around the world earn versus what they need to have a decent standard of living, and find ways to bridge this gap.[53]

A variation on the LICOP's Living Income is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Living Wage Calculator, which compares the local minimum wage to the amount of money needed to cover expenses beyond what is needed to merely survive across the United States.[56] The cost of living varies greatly if there are children or other dependents in the household.

Relevance[edit]

An outdated or flawed poverty measure is an obstacle for policymakers, researchers and academics trying to find solutions to the problem of poverty. This has implications for people. The federal poverty line is used by dozens of federal, state, and local agencies, as well as several private organizations and charities, to decide who needs assistance. The assistance can take many forms, but it is often difficult to put in place any type of aid without measurements which provide data. In a rapidly evolving economic climate, poverty assessment often aids developed countries in determining the efficacy of their programs and guiding their development strategy. In addition, by measuring poverty one receives knowledge of which poverty reduction strategies work and which do not,[57] helping to evaluate different projects, policies and institutions. To a large extent, measuring the poor and having strategies to do so keep the poor on the agenda, making the problem of political and moral concern.

Threshold limitations[edit]

It is hard to have exact number for poverty, as much data is collected through interviews, meaning income that is reported to the interviewer must be taken at face value.[58] As a result, data could not rightly represent the situations true nature, nor fully represent the income earned illegally. In addition, if the data were correct and accurate, it would still not mean serving as an adequate measure of the living standards, the well-being or economic position of a given family or household. Research done by Haughton and Khandker[59] finds that there is no ideal measure of well-being, arguing that all measures of poverty are imperfect. That is not to say that measuring poverty should be avoided; rather, all indicators of poverty should be approached with caution, and questions about how they are formulated should be raised.

As a result, depending on the indicator of economic status used, an estimate of who is disadvantaged, which groups have the highest poverty rates, and the nation's progress against poverty varies significantly. Hence, this can mean that defining poverty is not just a matter of measuring things accurately, but it also necessitates fundamental social judgments, many of which have moral implications.

National poverty lines[edit]

National estimates are based on population-weighted subgroup estimates from household surveys. Definitions of the poverty line do vary considerably among nations. For example, rich nations generally employ more generous standards of poverty than poor nations. Even among rich nations, the standards differ greatly. Thus, the numbers are not comparable among countries. Even when nations do use the same method, some issues may remain.[60]

United Kingdom[edit]

In the UK in 2006, "more than five million people – over a fifth (23 percent) of all employees – were paid less than £6.67 an hour". This value is based on a low pay rate of 60 percent of full-time median earnings, equivalent to a little over £12,000 a year for a 35-hour working week. In April 2006, a 35-hour week would have earned someone £9,191 a year – before tax or National Insurance".[61][62]

In 2019, the Low Pay Commission estimated that about 7% of people employed in the UK were earning at or below the National Minimum Wage.[63] In 2021, the Office for National Statistics found that 3.8% of jobs were paid below the National Minimum Wage, a decrease from 7.4% in 2020 but an increase from 1.4% in 2019.[64] They note that this increase from 2019 to 2021 is connected to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom.[64] The Guardian reported in 2021 that "almost 5m jobs, or one in six nationally, pay below the real living wage".[65]

India[edit]

India's official poverty level as of 2005[update] is split according to rural versus urban thresholds. For urban dwellers, the poverty line is defined as living on less than 538.60 rupees (approximately US$12) per month, whereas for rural dwellers, it is defined as living on less than 356.35 rupees per month (approximately US$7.50)[66] In 2019, the Indian government stated that 6.7% of its population is below its official poverty limit. As India is one of the fastest-growing economies in 2018, poverty is on the decline in the country, with close to 44 Indians escaping extreme poverty every minute, as per the World Poverty Clock. India lifted 271 million people out of poverty in a 10-year time period from 2005/06 to 2015/16.[67]

Iran[edit]

In 2008 Iran government report by central statistics had recommended 9.5 around million people living below poverty line.[68] As of August 2022 the Iranian economy suffered the highest inflation in 75 years; official statistics put the poverty line at 10 million tomans ($500), while the minimum wage given in the same year has been 5 million toman.[69][70]

Singapore[edit]

Singapore has experienced strong economic growth over the last ten years[when?] and has consistently ranked among the world's top countries in terms of GDP per capita.

Inequality has however increased dramatically over the same time span, yet there is no official poverty line in the country. Given Singapore's high level of growth and prosperity, many believe that poverty does not exist in the country, or that domestic poverty is not comparable to global absolute poverty. Such a view persists for a selection of reasons, and since there is no official poverty line, there is no strong acknowledgement that it exists.[71]

Yet, Singapore is not considering establishing an official poverty line, with Minister for Social and Family Development Chan Chun Sing claiming it would fail to represent the magnitude and scope of problems faced by the poor. As a result, social benefits and aids aimed at the poor would be a missed opportunity for those living right above such a line.[72]

United States[edit]

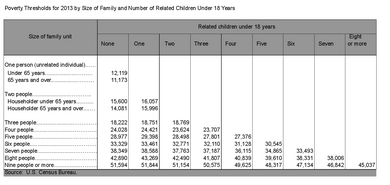

In the United States, the poverty thresholds are updated every year by Census Bureau. The threshold in the United States is updated and used for statistical purposes. In 2020, in the United States, the poverty threshold for a single person under 65 was an annual income of US$12,760, or about $35 per day. The threshold for a family group of four, including two children, was US$26,200, about $72 per day.[73] According to the US Census Bureau's American Community Survey 2018 One-year Estimates, 13.1% of Americans lived below the poverty line.[74]

Women and children[edit]

Women and children find themselves impacted by poverty more often when a part of single mother families.[75] The poverty rate of women has increasingly exceeded that of men's.[76] While the overall poverty rate is 12.3%, women poverty rate is 13.8% which is above the average and men are below the overall rate at 11.1%.[77][75] Women and children (as single mother families) find themselves as a part of low class communities because they are 21.6% more likely to fall into poverty. However, extreme poverty, such as homelessness, disproportionately affects males to a high degree.[78]

Racial minorities[edit]

A minority group is defined as "a category of people who experience relative disadvantage as compared to members of a dominant social group."[79] Minorities are traditionally separated into the following groups: African Americans, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics.[80] According to the current US Poverty statistics, Black Americans – 21%, Foreign born non-citizens – 19%, Hispanic Americans – 18%, and adults with a disability – 25%.[81] This does not include all minority groups, but these groups alone account for 85% of people under the poverty line in the United States.[82] Whites have a poverty rate of 8.7%; the poverty rate is more than double for Black and Hispanic Americans.[83]

Impacts on education[edit]

Living below the poverty threshold can have a major impact on a child's education.[84] The psychological stresses induced by poverty may affect a student's ability to perform well academically.[84] In addition, the risk of poor health is more prevalent for those living in poverty.[84] Health issues commonly affect the extent to which one can continue and fully take advantage of his or her education.[84] Poor students in the United States are more likely to dropout of school at some point in their education.[84] Research has also found that children living in poverty perform poorly academically and have lower graduation rates.[84] Impoverished children also experience more disciplinary issues in school than others.[84]

Schools in impoverished communities usually do not receive much funding, which can also set their students apart from those living in more affluent neighborhoods.[84] There is much dispute over whether upward mobility that brings a child out of poverty may or may not have a significant positive impact on his or her education; inadequate academic habits that form as early as preschool typically are unknown to improve despite changes in socioeconomic status.[84]

Impacts on healthcare[edit]

The nation's poverty threshold is issued by the Census Bureau.[85] According to the Office of Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation the threshold is statistically relevant and can be a solid predictor of people in poverty.[85] The reasoning for using Federal Poverty Level (FPL) is due to its action for distributive purposes under the direction of Health and Human Services. So FPL is a tool derived from the threshold but can be used to show eligibility for certain federal programs.[85] Federal poverty levels have direct effects on individuals' healthcare. In the past years and into the present government, the use of the poverty threshold has consequences for such programs like Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program.[86] The benefits which different families are eligible for are contingent on FPL. The FPL, in turn, is calculated based on federal numbers from the previous year.[86]

The benefits and qualifications for federal programs are dependent on number of people on a plan and the income of the total group.[86] For 2019, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services enumerate what the line is for different families. For a single person, the line is $12,490 and up to $43,430 for a family of 8, in the lower 48 states.[85] Another issue is reduced-cost coverage. These reductions are based on income relative to FPL, and work in connection with public health services such as Medicaid.[87] The divisions of FPL percentages are nominally, above 400%, below 138% and below 100% of the FPL.[87] After the advent of the American Care Act, Medicaid was expanded on states bases.[87] For example, enrolling in the ACA kept the benefits of Medicaid when the income was up to 138% of the FPL.[87]

Poverty mobility and healthcare[edit]

Health Affairs along with analysis by Georgetown found that public assistance does counteract poverty threats between 2010 and 2015.[88] In regards to Medicaid, child poverty is decreased by 5.3%, and Hispanic and Black poverty by 6.1% and 4.9% respectively.[88] The reduction of family poverty also has the highest decrease with Medicaid over other public assistance programs.[88] Expanding state Medicaid decreased the amount individuals paid by an average of $42, while it increased the costs to $326 for people not in expanded states. The same study analyzed showed 2.6 million people were kept out of poverty by the effects of Medicaid.[88] From a 2013–2015 study, expansion states showed a smaller gap in health insurance between households making below $25,000 and above $75,000.[89] Expansion also significantly reduced the gap of having a primary care physician between impoverished and higher income individuals.[89] In terms of education level and employment, health insurance differences were also reduced.[89] Non-expansion also showed poor residents went from a 22% chance of being uninsured to 66% from 2013 to 2015.[89]

Poverty dynamics[edit]

Living above or below the poverty threshold is not necessarily a position in which an individual remains static.[90] As many as one in three impoverished people were not poor at birth; rather, they descended into poverty over the course of their life.[84] Additionally, a study which analyzed data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) found that nearly 40% of 20-year-olds received food stamps at some point before they turned 65.[91] This indicates that many Americans will dip below the poverty line sometime during adulthood, but will not necessarily remain there for the rest of their life.[91] Furthermore, 44% of individuals who are given transfer benefits (other than Social Security) in one year do not receive them the next.[90] Over 90% of Americans who receive transfers from the government stop receiving them within 10 years, indicating that the population living below the poverty threshold is in flux and does not remain constant.[90]

Cutoff issues[edit]

Most experts and the public agree that the official poverty line in the United States is substantially lower than the actual cost of basic needs. In particular, a 2017 Urban Institute study found that 61% of non-elderly adults earning between 100 and 200% of the poverty line reported at least one material hardship, not significantly different from those below the poverty line. The cause of the discrepancy is believed to be an outdated model of spending patterns based on actual spending in the year 1955; the number and proportion of material needs has risen substantially since then.

Variability[edit]

The US Census Bureau calculates the poverty line the same throughout the US regardless of the cost-of-living in a state or urban area. For instance, the cost-of-living in California, the most populous state, was 42% greater than the US average in 2010, while the cost-of-living in Texas, the second-most populous state, was 10% less than the US average.[citation needed] In 2017, California had the highest poverty rate in the country when housing costs are factored in, a measure calculated by the Census Bureau known as "the supplemental poverty measure".[92]

Government transfers to alleviate poverty[edit]

In addition to wage and salary income, investment income and government transfers such as SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps) and housing subsidies are included in a household's income. Studies measuring the differences between income before and after taxes and government transfers, have found that without social support programs, poverty would be roughly 30% to 40% higher than the official poverty line indicates.[93][94]

See also[edit]

- Asset poverty

- Guaranteed minimum income

- Income deficit

- List of countries by percentage of population living in poverty

- Living wage

- Measuring poverty

- Poor person

- Millennium Development Goals

- Social safety net

- Sustainable Development Goal 1

References[edit]

- ^ webster, The breadline. "The breadline".

- ^ Ravallion, Martin Poverty freak: A Guide to Concepts and Methods. Living Standards Measurement Papers, The World

- ^ Poverty Lines – Martin Ravallion, in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition, London: Palgrave Macmillan

- ^ Chassagnon, A (2019). "Efficiency and equity" (PDF). Paris School of Economics.

- ^ Hagenaars, Aldi & de Vos, Klaas The Definition and Measurement of Poverty. Journal of Human Resources, 1988

- ^ Hagenaars, Aldi & van Praag, Bernard A Synthesis of Poverty Line Definitions. Review of Income and Wealth, 1985

- ^ "World Bank". The World Bank. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "World Bank 2022 poverty lines". Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "2022 World Bank poverty lines". Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "PovcalNet". iresearch.worldbank.org. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zach (14 December 2014). "The world's victory over extreme poverty, in one chart". Vox. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Gillie, Alan (1996). "The Origin of the Poverty Line". Economic History Review. 49 (4): 715–730 [p. 726]. doi:10.2307/2597970. JSTOR 2597970.

- ^ Boyle, David (2000). The Tyranny of Numbers. HarperCollins. p. 116. ISBN 0-00-257157-9.

- ^ a b Rowntree, Benjamin Seebohm (1901). Poverty: A Study in Town Life. Macmillan and Co. p. 298

- ^ "History of poverty thresholds".

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "Principles and Practice in Measuring Global Poverty". The World Bank. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "World Bank Forecasts Global Poverty to Fall Below 10% for First Time; Major Hurdles Remain in Goal to End Poverty by 2030". www.worldbank.org. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Ravallion, Martin; Chen Shaohua & Sangraula, Prem Dollar a day The World Bank Economic Review, 23, 2, 2009, pp. 163–84

- ^ Hildegard Lingnau (19 February 2016). "Major breakthrough". D+C, development&cooperation. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Sachs, Jeffrey D. The End of Poverty 2005, p. 20

- ^ Hickel, Jason (1 November 2015). "Could you live on $1.90 a day? That's the international poverty line". The Guardian.

- ^ Robert C. Allen, 2017. " Absolute Poverty: When Necessity Displaces Desire REVISED, " Working Papers 20170005, New York University Abu Dhabi, Department of Social Science, revised Jun 2017.

- ^ a b "The World Employment Programme at ILO" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2014.

- ^ a b Jolly, Richard (October 1976). "The World Employment Conference: The Enthronement of Basic Needs". Development Policy Review. A9 (2): 31–44. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.1976.tb00338.x.

- ^ Denton, John A. (1990). Society and the official world: a reintroduction to sociology. Dix Hills, N.Y: General Hall. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-930390-94-5.

- ^ a b "Indicators of Poverty and Hunger" (PDF). Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Ghai, Dharam (June 1978). "Basic Needs and its Critics". Institute of Development Studies. 9 (4): 16–18. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.1978.mp9004004.x.

- ^ a b Eskelinen, Teppo (2011). "Relative Poverty". Encyclopedia of Global Justice. pp. 942–943. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9160-5_182. ISBN 978-1-4020-9159-9.

- ^ European Commission. Statistical Office of the European Union (2018). Living conditions in Europe. Publications Office. doi:10.2785/39876. ISBN 978-92-79-86498-8. p. 8:

In 2016, median equivalised net income varied considerably across the EU Member States

- ^ a b "Relative vs Absolute Poverty: Defining Different Types of Poverty". Habitat for Humanity GB. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Raphael, Dennis (June 2009). "Poverty, Human Development, and Health in Canada: Research, Practice, and Advocacy Dilemmas". Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 41 (2): 7–18. PMID 19650510.

- ^ Child poverty in rich nations: Report card no. 6 (Report). Innocenti Research Centre. 2005.

- ^ "Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2008.

- ^ Human development report: Capacity development: Empowering people and institutions (Report). Geneva: United Nations Development Program. 2008.

- ^ "Child Poverty". Ottawa, ON: Conference Board of Canada. 2013.

- ^ Ive Marx; Karel van den Bosch. "How poverty differs from inequality on poverty management in an enlarged EU context: Conventional and alternate approaches" (PDF). Antwerp, Belgium: Centre for Social Policy. [permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Bradshaw, Jonathan; Chzhen, Yekaterina; Main, Gill; Martorano, Bruno; Menchini, Leonardo; de Neubourg, Chris (31 January 2012). "Relative Income Poverty Among Children in Rich Countries". Innocenti Working Papers. doi:10.18356/3afdf450-en.

- ^ A League Table of Child Poverty in Rich Nations (Report). Innocenti Report Card No.1. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

- ^ Adam Smith (1776). An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Vol. 5.

- ^ a b c d Peter Adamson; UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre (2012). Measuring child poverty: New league tables of child poverty in the world's rich countries (PDF) (Report). UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre Report Card. Florence, Italy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Galbraith, J. K. (1958). The Affluent Society. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ Minority [Republican] views, p. 46 in U.S. Congress, Report of the Joint Economic Committee on the January 1964 Economic Report of the President with Minority and Additional Views (Report). Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. January 1964.

- ^ Friedman, Rose. D. (1965). Poverty: Definition and Perspective. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research (Report). Washington, D.C.

- ^ Fuchs, Victor (Summer 1967). "Redefining Poverty and Redistributing Income". The Public Interest. 8: 88. ProQuest 1298125552.

- ^ Ravallion, Martin; Chen, Shaohua (August 2017). "Welfare-Consistent Global Poverty Measures". National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper Series. doi:10.3386/w23739. SSRN 3027843.

- ^ Foster, James E. (1998). "Absolute versus Relative Poverty". The American Economic Review. 88 (2): 335–341. JSTOR 116944.

- ^ Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. London: Penguin.

- ^ Callan, T; Nolan, Brian; Whelan, Christopher T (1993). "Resources, Deprivation and the Measurement of Poverty" (PDF). Journal of Social Policy. 22 (2): 141–72. doi:10.1017/s0047279400019280. hdl:10197/1061. S2CID 55675120.

- ^ Michael Blastland (31 July 2009). "Just what is poor?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Bardone, Laura; Guio, Anne-Catherine (2005). "In-Work Poverty: New commonly agreed indicators at the EU level". Statistics in Focus.

- ^ "Inequality in Focus, October 2013: Analyzing the World Bank's Goal of Achieving "Shared Prosperity"". World Bank. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ a b c "Living Income | Living Income Community of Practice". livingincome. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Guidance manual on calculating and visualizing the income gap to a Living Income Benchmark Prepared for the Living Income Community of Practice The Committee on Sustainability Assessment (COSA) and KIT Royal Tropical Institute July 2020

- ^ "Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020". World Bank. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "Living Wage Calculator". livingwage.mit.edu. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "Measuring Poverty". World Bank. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Haveman, Robert (1993). "Who Are the Nation's 'Truly Poor'? Problems and Pitfalls in (Re)defining and Measuring Poverty". The Brookings Review. 11 (1): 24–27. doi:10.2307/20080360. JSTOR 20080360.

- ^ Haughton, Jonathan; Khandker, Shahidur R. (2009). Handbook on Poverty + Inequality. World Bank Publications. ISBN 978-0-8213-7614-0. OCLC 568421757.[page needed]

- ^ "http://inequalitywatch.eu/spip.php?article99" Eurostat 2010

- ^ Cooke, Graeme; Lawton, Kayte (January 2008). "Working out of Poverty: A study of the low paid and the working poor" (PDF). Institute for Public Policy Research.

- ^ IPPR Article: "Government must rescue 'forgotten million children' in poverty" Archived 25 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Francis-Devine, Brigid (2021). "National Minimum Wage Statistics: Research Briefing". UK Parliament. House of Commons. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b White, Nicola (2021). "Low and high pay in the UK: 2021". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Toynbee, Polly (16 November 2021). "Levelling up? If anything, things are getting worse for the lowest paid in the UK". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Poverty Estimates for 2004-05" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ "The start of a new poverty narrative". 19 June 2018. Brookings Institution, June 2018

- ^ "Millions live below the poverty line in Iran". Thenationalnews.com. 4 August 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Iranian Families Pushed Below Poverty Line by Low National Minimum Wage". 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Iranian Workers Get A 'Humiliating' Wage Increase". En.radiofarda.com. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Donaldson, John A.; Loh, Jacqueline; Mudaliar, Sanushka; Kadir, Mumtaz Md; Wu, Biqi; Yeoh, Lam Keong (2013). "Measuring Poverty in Singapore: Frameworks for Consideration". Social Space: 58–66.

- ^ migration (23 October 2013). "Why setting a poverty line may not be helpful: Minister Chan Chun Sing". The Straits Times. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines" (PDF). Federal Register. 85: 3060. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "2018 Poverty Rate in the United States". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ a b "The Straight Facts on Women in Poverty" (PDF). cdn.americanprogressaction.org. October 2008.

- ^ McLanahan, Sara S.; Kelly, Erin L. (2006). "The Feminization of Poverty". Handbook of the Sociology of Gender. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. pp. 127–145. doi:10.1007/0-387-36218-5_7. ISBN 978-0-387-32460-9.

- ^ "Basic Statistics". Talk Poverty. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Demographic Data Project: Gender and Individual Homelessness". endhomelessness.org. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Poverty Statistics". federalsafetynet.com. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Poverty Statistics". federalsafteynet.com. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "U.S Poverty Stats". Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Poverty Statistics". federalfasteynet.com. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "United States Population". worldpopulationreveiw.com. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Engle, Patrice L.; Black, Maureen M. (25 July 2008). "The Effect of Poverty on Child Development and Educational Outcomes". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1136 (1): 243–256. Bibcode:2008NYASA1136..243E. doi:10.1196/annals.1425.023. PMID 18579886. S2CID 7576265.

- ^ a b c d "Poverty Guidelines". ASPE. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "Federal Poverty Level (FPL) - HealthCare.gov Glossary". HealthCare.gov. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Will you receive an Obamacare premium subsidy?". healthinsurance.org. 27 December 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Research Update: Medicaid Pulls Americans Out Of Poverty, Updated Edition". Center For Children and Families. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Griffith, Kevin; Evans, Leigh; Bor, Jacob (August 2017). "The Affordable Care Act Reduced Socioeconomic Disparities In Health Care Access". Health Affairs. 36 (8): 1503–1510. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0083. PMC 8087201. PMID 28747321.

- ^ a b c Fullerton, Don; Rao, Nirupama (August 2016). "The Lifecycle of the 47%". National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper Series. doi:10.3386/w22580. S2CID 157334511. SSRN 2832584.

- ^ a b Grieger, Lloyd D.; Danziger, Sheldon H. (1 November 2011). "Who Receives Food Stamps During Adulthood? Analyzing Repeatable Events With Incomplete Event Histories". Demography. 48 (4): 1601–1614. doi:10.1007/s13524-011-0056-x. PMID 21853399. S2CID 45907852.

- ^ Matt Levin (2 October 2017). "Expensive homes make California poorest state". San Francisco Chronicle. p. C1.

- ^ Kenworthy, L (1999). "Do social-welfare policies reduce poverty? A cross-national assessment" (PDF). Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–39. doi:10.1093/sf/77.3.1119. hdl:10419/160860.

- ^ Bradley, D; Huber, E; Moller, S.; Nielson, F; Stephens, JD (2003). "Determinants of relative poverty in advanced capitalist democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (3): 22–51. doi:10.2307/3088901. JSTOR 3088901.

Further reading[edit]

- Shweparde, Jon; Robert W. Greene (2003). Sociology and You. Ohio: Glencoe McGraw-Hill. p. A-22. ISBN 978-0-07-828576-9. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010.

- Alan Gillie, "The Origin of the Poverty Line", Economic History Review, XLIX/4 (1996), 726

- Villemez, Wayne J. (2001). "Poverty". Encyclopedia of Sociology (PDF). New York: Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- Critiquing the Dollar-a-Day Idea of Poverty, Harald Eustachius Tomintz, 27 January 2021, Mises Institute

External links[edit]

- The History of the Official Poverty Measure, United States Bureau of the Census

- Fisher, Gordon (16 December 2005). "Relative or Absolute – New Light on the Behavior of Poverty Lines Over Time". Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 16 January 2008.