Pegasus (constellation)

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Peg |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Pegasi |

| Pronunciation | /ˈpɛɡəsəs/, genitive /ˈpɛɡəsaɪ/ |

| Symbolism | the Winged Horse |

| Right ascension | 21h 12.6m to 00h 14.6m [1] |

| Declination | +2.33° to +36.61°[1] |

| Quadrant | NQ4 |

| Area | 1121 sq. deg. (7th) |

| Main stars | 9, 17 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 88 |

| Stars with planets | 12 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 5 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 3 |

| Brightest star | ε Peg (Enif) (2.38m) |

| Messier objects | 1 |

| Meteor showers | July Pegasids |

| Bordering constellations | Andromeda Lacerta Cygnus Vulpecula Delphinus Equuleus Aquarius Pisces |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −60°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of October. | |

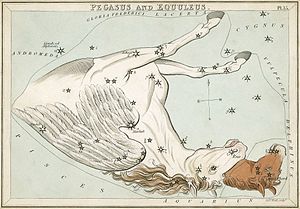

Pegasus is a constellation in the northern sky, named after the winged horse Pegasus in Greek mythology. It was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and is one of the 88 constellations recognised today.

With an apparent magnitude varying between 2.37 and 2.45, the brightest star in Pegasus is the orange supergiant Epsilon Pegasi, also known as Enif, which marks the horse's muzzle. Alpha (Markab), Beta (Scheat), and Gamma (Algenib), together with Alpha Andromedae (Alpheratz) form the large asterism known as the Square of Pegasus. Twelve star systems have been found to have exoplanets. 51 Pegasi was the first Sun-like star discovered to have an exoplanet companion.

Mythology[edit]

The Babylonian constellation IKU (field) had four stars of which three were later part of the Greek constellation Hippos (Pegasus).[2] Pegasus, in Greek mythology, was a winged horse with magical powers. One myth regarding his powers says that his hooves dug out a spring, Hippocrene, which blessed those who drank its water with the ability to write poetry. Pegasus was born when Perseus cut off the head of Medusa, who was impregnated by the god Poseidon. He was born with Chrysaor from Medusa's blood.[3] Eventually, it became the horse for Bellerophon, who was asked to kill the Chimera and succeeded with the help of Athena and Pegasus. Despite this success, after the death of his children, Bellerophon asked Pegasus to take him to Mount Olympus. Though Pegasus agreed, he plummeted back to Earth after Zeus either threw a thunderbolt at him or sent a gadfly to make Pegasus buck him off.[4][5] In ancient Persia, Pegasus was depicted by al-Sufi as a complete horse facing east, unlike most other uranographers, who had depicted Pegasus as half of a horse, rising out of the ocean. In al-Sufi's depiction, Pegasus's head is made up of the stars of Lacerta the lizard. Its right foreleg is represented by β Peg and its left foreleg is represented by η Peg, μ Peg, and λ Peg; its hind legs are marked by 9 Peg. The back is represented by π Peg and μ Cyg, and the belly is represented by ι Peg and κ Peg.[4]

In Chinese astronomy, the modern constellation of Pegasus lies in The Black Tortoise of the north (北方玄武), where the stars were classified in several separate asterisms of stars.[6] Epsilon and Theta Pegasi are joined with Alpha Aquarii to form Wei 危 "rooftop", with Theta forming the roof apex.[7]

In Hindu astronomy, the Great Square of Pegasus contained the 26th and 27th lunar mansions. More specifically, it represented a bedstead that was a resting place for the Moon.[4]

For the Warrau and Arawak peoples in Guyana the stars in the Great Square, corresponding to parts of Pegasus and of Andromeda, represented a barbecue, taken up to the sky by the seven hunters of the myth of Siritjo.[4][8]

Characteristics[edit]

Covering 1121 square degrees, Pegasus is the seventh-largest of the 88 constellations. Pegasus is bordered by Andromeda to the north and east, Lacerta to the north, Cygnus to the northwest, Vulpecula, Delphinus and Equuleus to the west, Aquarius to the south and Pisces to the south and east. The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the IAU in 1922, is "Peg".[9] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined as a polygon of 35 segments. In the equatorial coordinate system the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 21h 12.6m and 00h 14.6m , while the declination coordinates are between 2.33° and 36.61°.[1] Its position in the Northern Celestial Hemisphere means that the whole constellation is visible to observers north of 53°S.[10][a]

Pegasus is dominated by a roughly square asterism, although one of the stars, Delta Pegasi or Sirrah, is now officially considered to be Alpha Andromedae, part of Andromeda, and is more usually called "Alpheratz". Traditionally, the body of the horse consists of a quadrilateral formed by the stars α Peg, β Peg, γ Peg, and α And. The front legs of the winged horse are formed by two crooked lines of stars, one leading from η Peg to κ Peg and the other from μ Peg to 1 Pegasi. Another crooked line of stars from α Peg via θ Peg to ε Peg forms the neck and head; ε is the snout.

Features[edit]

Stars[edit]

Bayer catalogued what he counted as 23 stars in the constellation, giving them the Bayer designations Alpha to Psi. He saw Pi Pegasi as one star, and was uncertain of its brightness, wavering between magnitude 4 and 5. Flamsteed labelled this star 29 Pegasi, but Bode concluded that the stars 27 and 29 Pegasi should be Pi1 and Pi2 Pegasi and that Bayer had seen them as a single star.[11] Flamsteed added lower case letters e through to y, omitting A to D as they had been used on Bayer's chart to designate neighbouring constellations and the equator.[12] He numbered 89 stars (now with Flamsteed designations), though 6 and 11 turned out to be stars in Aquarius.[13] Within the constellation's borders there are 177 stars of apparent magnitude 6.5 or greater.[b][10]

Epsilon Pegasi, also known as Enif, marks the horse's muzzle. The brightest star in Pegasus, is an orange supergiant of spectral type K21b that is around 12 times as massive as the Sun and is around 690 light-years distant from Earth.[15] It is an irregular variable, its apparent magnitude varying between 2.37 and 2.45.[16] Lying near Enif is AG Pegasi, an unusual star that brightened to magnitude 6.0 around 1885 before dimming to magnitude 9. It is composed of a red giant and white dwarf, estimated to be around 2.5 and 0.6 times the mass of the Sun respectively. With its outburst taking over 150 years, it has been described as the slowest nova ever recorded.[17]

Three stars with Bayer designations that lie within the Great Square are variable stars. Phi and Psi Pegasi are pulsating red giants, while Tau Pegasi (the proper name is Salm[18]), is a Delta Scuti variable—a class of short period (six hours at most) pulsating stars that have been used as standard candles and as subjects to study astroseismology.[19] Rotating rapidly with a projected rotational velocity of 150 km s−1, Kerb is almost 30 times as luminous as the Sun and has a pulsation period of 56.5 minutes. With an outer atmosphere at an effective temperature of 7,762 K, it is a white star with a spectral type of A5IV.[20]

Zeta, Xi, Rho and Sigma Pegasi mark the horse's neck.[21] The brightest of these with a magnitude of 3.4 is Zeta, also traditionally known as Homam. Lying seven degrees southwest of Markab, it is a blue-white main sequence star of spectral type B8V located around 209 light-years distant.[22] It is a slowly pulsating B star that varies slightly in luminosity with a period of 22.952 ± 0.804 hours, completing 1.04566 cycles per day.[23] Xi lies 2 degrees northeast, and is a yellow-white main sequence star of spectral type F6V that is 86% larger and 17% more massive that the Sun, and radiate 4.5 times the solar luminosity.[24] It has a red dwarf companion that is 192.3 au distant.[25] If (as is likely) the smaller star is in orbit around the larger star, then it would take around 2000 years to complete a revolution.[26] Theta Pegasi marks the horse's eye.[21] Also known as Biham, it is a 3.43-magnitude white main sequence star of spectral type A2V, around 1.8 times as massive, 24 times as luminous, and 2.3 times as wide as the Sun.[27]

Alpha (Markab), Beta (Scheat), and Gamma (Algenib), together with Alpha Andromedae (Alpheratz or Sirrah) form the large asterism known as the Square of Pegasus. The brightest of these, Alpheratz was also known as both Delta Pegasi and Alpha Andromedae before being placed in Andromeda in 1922 with the setting of constellation boundaries. The second brightest star is Scheat, a red giant of spectral type M2.5II-IIIe located around 196 light-years away from Earth.[28] It has expanded until it is some 95 times as large, and has a total luminosity 1,500 times that of the Sun.[29] Beta Pegasi is a semi-regular variable that varies from magnitude 2.31 to 2.74 over a period of 43.3 days.[30] Markab and Algenib are blue-white stars of spectral types B9III and B2IV located 133 and 391 light-years distant respectively.[31][32] Appearing to have moved off the main sequence as their core hydrogen supply is being or has been exhausted, they are enlarging and cooling to eventually become red giant stars.[33][34] Markab has an apparent magnitude of 2.48,[31] while Algenib is a Beta Cephei variable that varies between magnitudes 2.82 and 2.86 every 3 hours 38 minutes, and also exhibits some slow pulsations every 1.47 days.[35]

Eta and Omicron Pegasi mark the left knee and Pi Pegasi the left hoof, while Iota and Kappa Pegasi mark the right knee and hoof.[21] Also known as Matar, Eta Pegasi is the fifth-brightest star in the constellation. Shining with an apparent magnitude of 2.94, it is a multiple star system composed of a yellow giant of spectral type G2 and a yellow-white main sequence star of spectral type A5V that are 3.2 and 2.0 times as massive as the Sun. The two revolve around each other every 2.24 years. Farther afield is a binary system of two G-type main sequence stars, that would take 170,000 years to orbit the main pair if they are in fact related.[36] Omicron Pegasi has a magnitude of 4.79. Located 300 ± 20 light-years distant from Earth,[37] it is a white subgiant that has begun to cool, expand and brighten as it exhausts its core hydrogen fuel and moves off the main sequence.[38] Pi1 and Pi2 Pegasi appear as an optical double to the unaided eye as they are separated by 10 arcminutes, and are not a true binary system.[39] Located 289 ± 8 light-years distant,[37] Pi1 is an ageing yellow giant of spectral type G6III, 1.92 times as massive and around 200 times as luminous as the Sun.[40] Pi2 is a yellow-white subgiant that is 2.5 times as massive as the Sun and has expanded to 8 times the Sun's radius and brightened to 92 times the Sun's luminosity. It is surrounded by a circumstellar disk spinning at 145 km a second,[39] and is 263 ± 4 light-years distant from Earth.[37]

IK Pegasi is a close binary comprising an A-type main-sequence star[41] and white dwarf[42] in very close orbit; the latter a candidate for a future type Ia supernova[43] as its main star runs out of core hydrogen fuel and expands into a giant and transfers material to the smaller star.

Twelve star systems have been found to have exoplanets. 51 Pegasi was the first Sun-like star discovered to have an exoplanet companion;[44] 51 Pegasi b (unofficially named Bellerophon,[45] officially named Dimidium[46]) is a hot Jupiter close to its star, completing an orbit every four days. Spectroscopic analysis of HD 209458 b, an extrasolar planet in this constellation, has provided the first evidence of atmospheric water vapor beyond the Solar System,[47][48][49] while extrasolar planets orbiting the star HR 8799 also in Pegasus are the first to be directly imaged.[50][51][52] V391 Pegasi is a hot subdwarf star that has been found to have a planetary companion.[53]

Named stars[edit]

| Name[18] | Bayer designation | Origin | Meaning | Light Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markab | α | Arabic | the saddle of the horse | 133 |

| Scheat | β | Arabic | the upper arm | 196 |

| Algenib | γ | Arabic | the side / wing | 391 |

| Enif | ε | Arabic | nose | 690 |

| Homam | ζ | Arabic | man of high spirit | 204 |

| Matar | η | Arabic | lucky rain of shooting stars | 167 |

| Biham | θ | Arabic | the livestocks | 67 |

| Sadalbari | μ | Arabic | luck star of the splendid one | 106 |

| Salm | τ | Arabic | the leathern bucket | 162 |

| Alkarab | υ | Arabic | the bucket-rope | 170 |

Deep-sky objects[edit]

M15 (NGC 7078) is a globular cluster of magnitude 6.4, 34,000 light-years from Earth. It is a Shapley class IV cluster,[54] which means that it is fairly rich and concentrated towards its center. M15 was discovered in 1746 by Jean-Dominique Maraldi.[55] Pease 1 is a planetary nebula located within the globular cluster and was the first planetary nebula known to exist within a globular cluster.[56] It has an apparent magnitude of 15.5.[57]

NGC 7331 is a spiral galaxy located in Pegasus, 38 million light-years distant with a redshift of 0.0027. It was discovered by musician-astronomer William Herschel in 1784 and was later one of the first nebulous objects to be described as "spiral" by William Parsons. Another of Pegasus's galaxies is NGC 7742, a Type 2 Seyfert galaxy. Located at a distance of 77 million light-years with a redshift of 0.00555, it is an active galaxy with a supermassive black hole at its core. Its characteristic emission lines are produced by gas moving at high speeds around the central black hole.[58]

Pegasus is also noted for its more unusual galaxies and exotic objects. Einstein's Cross is a quasar that has been lensed by a foreground galaxy. The elliptical galaxy is 400 million light-years away with a redshift of 0.0394, but the quasar is 8 billion light-years away. The lensed quasar resembles a cross because the gravitational force of the foreground galaxy on its light creates four images of the quasar.[58] Stephan's Quintet is another unique object located in Pegasus. It is a cluster of five galaxies at a distance of 300 million light-years and a redshift of 0.0215. First discovered by Édouard Stephan, a Frenchman, in 1877, the Quintet is unique for its interacting galaxies. Two of the galaxies in the middle of the group have clearly begun to collide, sparking massive bursts of star formation and drawing off long "tails" of stars. Astronomers have predicted that all five galaxies may eventually merge into one large elliptical galaxy.[58]

Namesakes[edit]

USS Pegasus (AK-48) and USS Pegasus (PHM-1) are United States navy ships named after the constellation "Pegasus".

The Beyblade top Storm Pegasus 105RF and its evolutions Galaxy Pegasus W105R2F and Cosmic Pegasus F:D are based on Pegasus constellation.

Pegasus Seiya, main character from the manga and anime Saint Seiya, was named after the constellation Pegasus.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between the 53°S and 87°S, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[10]

- ^ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[14]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Pegasus, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Thurston, Hugh (1996). Early Astronomy. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-387-94822-5.

- ^ Ovid (1986). Melville, A.D. (ed.). Metamorphoses. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-19-283472-X.

- ^ a b c d Staal 1988, pp. 27–32

- ^ Conner, Nancy. The Everything Classical Mythology Book: from the Heights of Mount Olympus to the Depths of the Underworld - All You Need to Know about the Classical Myths. 2nd ed., Adams Media, 2010.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Charting the Chinese sky". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Schlegel 1967, pp. 233–34.

- ^ Magaña, Edmundo; Jara, Fabiola (1982). "The Carib sky". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 68 (1): 114. doi:10.3406/jsa.1982.2212.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ a b c Ian Ridpath. "Constellations: Lacerta–Vulpecula". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Wagman 2003, p. 235.

- ^ Wagman 2003, p. 236.

- ^ Wagman 2003, p. 448.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). "The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Sky Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Epsilon Pegasi -- Pulsating Variable Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (7 June 2011). "Epsilon Pegasi". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Kenyon, Scott J.; Mikolajewska, Joanna; Mikolajewski, Maciej; Polidan, Ronald S.; Slovak, Mark H. (1993). "Evolution of the symbiotic binary system AG Pegasi - The slowest classical nova eruption ever recorded" (PDF). Astronomical Journal. 106 (4): 1573–98. Bibcode:1993AJ....106.1573K. doi:10.1086/116749.

- ^ a b "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Templeton, Matthew (16 July 2010). "Delta Scuti and the Delta Scuti Variables". Variable Star of the Season. AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers). Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Balona, L. A.; Dziembowski, W. A. (1999). "Excitation and visibility of high-degree modes in stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 309 (1): 221–32. Bibcode:1999MNRAS.309..221B. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.1999.02821.x.

- ^ a b c Wagman 2003, p. 513.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (16 November 2007). "Homam (Zeta Pegasi)". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Goebel, John H. (2007). "Gravity Probe B Photometry and Observations of ζ Pegasi: An SPB Variable Star". The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 119 (855): 483–93. Bibcode:2007PASP..119..483G. doi:10.1086/518618.

- ^ Ghezzi, L.; Cunha, K.; Smith, V. V.; de Araújo, F. X.; Schuler, S. C.; de la Reza, R. (2010). "Stellar Parameters and Metallicities of Stars Hosting Jovian and Neptunian Mass Planets: A Possible Dependence of Planetary Mass on Metallicity". The Astrophysical Journal. 720 (2): 1290–1302. arXiv:1007.2681. Bibcode:2010ApJ...720.1290G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/720/2/1290. S2CID 118565025.

- ^ Moro-Martín, A.; Marshall, J. P.; Kennedy, G.; Sibthorpe, B.; Matthews, B. C.; Eiroa, C.; Wyatt, M. C.; Lestrade, J.-F.; Maldonado, J.; Rodriguez, D.; Greaves, J. S.; Montesinos, B.; Mora, A.; Booth, M.; Duchêne, G.; Wilner, D.; Horner, J. (2015). "Does the Presence of Planets Affect the Frequency and Properties of Extrasolar Kuiper Belts? Results from the Herschel Debris and Dunes Surveys". The Astrophysical Journal. 801 (2): 28. arXiv:1501.03813. Bibcode:2015ApJ...801..143M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/801/2/143. S2CID 55170390. 143.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (30 November 2007). "Xi Pegasi". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Boyajian, Tabetha S.; von Braun, Kaspar; van Belle, Gerard; Farrington, Chris; Schaefer, Gail; Jones, Jeremy; White, Russel; McAlister, Harold A.; ten Brummelaar, Theo A.; Ridgway, Stephen; Gies, Douglas; Sturmann, Laszlo; Sturmann, Judit; Turner, Nils H.; Goldfinger, P. J.; Vargas, Norm (2013). "Stellar Diameters and Temperatures. III. Main-sequence A, F, G, and K Stars: Additional High-precision Measurements and Empirical Relations". The Astrophysical Journal. 771 (1): 31. arXiv:1306.2974. Bibcode:2013ApJ...771...40B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/771/1/40. S2CID 14911430. 40. See Table 3.

- ^ "Beta Pegasi -- Pulsating Variable Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (22 May 2009). "Scheat (Beta Pegasi)". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (25 August 2009). "Beta Pegasi". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Alpha Pegasi -- Variable Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "Gamma Pegasi -- Variable Star of Beta Cephei type". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Markab (Alpha Pegasi)". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Algenib (Gamma Pegasi)". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (26 March 2011). "Gamma Pegasi". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Matar (Eta Pegasi)". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ a b c van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the New Hipparcos Reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Gray, David F. (2014). "Precise Rotation Rates for Five Slowly Rotating a Stars". The Astronomical Journal. 147 (4): 13. Bibcode:2014AJ....147...81G. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/147/4/81. S2CID 121928906. 81.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. "Pi Pegasi". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Takeda, Yoichi; Sato, Bun'ei; Murata, Daisuke (2008). "Stellar Parameters and Elemental Abundances of Late-G Giants". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 60 (4): 781–802. arXiv:0805.2434. Bibcode:2008PASJ...60..781T. doi:10.1093/pasj/60.4.781. S2CID 16258166.

- ^ Skiff, B. A. (October 2014), "Catalogue of Stellar Spectral Classifications", Lowell Observatory, VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/mk, Bibcode:2014yCat....1.2023S.

- ^ Barstow, M. A.; Holberg, J. B.; Koester, D. (1994), "Extreme Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry of HD16538 and HR:8210 Ik-Pegasi", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 270 (3): 516, Bibcode:1994MNRAS.270..516B, doi:10.1093/mnras/270.3.516

- ^ Wonnacott, D.; Kellett, B. J.; Stickland, D. J. (1993), "IK Peg - A nearby, short-period, Sirius-like system", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 262 (2): 277–284, Bibcode:1993MNRAS.262..277W, doi:10.1093/mnras/262.2.277

- ^ Mayor, Michael; Queloz, Didier (1995). "A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star". Nature. 378 (6555): 355–359. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..355M. doi:10.1038/378355a0. S2CID 4339201.

- ^ University of California at Berkeley News Release 1996-17-01

- ^ Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released, International Astronomical Union, 15 December 2015.

- ^ Water Found in Extrasolar Planet's Atmosphere – Space.com

- ^ "Hubble Traces Subtle Signals of Water on Hazy Worlds". NASA. December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ Deming, Drake; et al. (September 10, 2013). "Infrared Transmission Spectroscopy of the Exoplanets HD 209458b and XO-1b Using the Wide Field Camera-3 on the Hubble Space Telescope". Astrophysical Journal. 774 (2): 95. arXiv:1302.1141. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774...95D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/774/2/95. S2CID 10960488.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel (13 November 2008). "Scientists publish first direct images of extrasolar planets". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "Gemini releases historic discovery image of planetary first family" (Press release). Gemini Observatory. 13 November 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "Astronomers capture first images of newly-discovered solar system" (Press release). W. M. Keck Observatory. 13 November 2008. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Silvotti, R.; Schuh, S.; Janulis, R.; Solheim, J. -E.; Bernabei, S.; Østensen, R.; Oswalt, T. D.; Bruni, I.; Gualandi, R.; Bonanno, A.; Vauclair, G.; Reed, M.; Chen, C. -W.; Leibowitz, E.; Paparo, M.; Baran, A.; Charpinet, S.; Dolez, N.; Kawaler, S.; Kurtz, D.; Moskalik, P.; Riddle, R.; Zola, S. (2007), "A giant planet orbiting the 'extreme horizontal branch' star V391 Pegasi" (PDF), Nature, 449 (7159): 189–91, Bibcode:2007Natur.449..189S, doi:10.1038/nature06143, PMID 17851517, S2CID 4342338

- ^ Shapley, Harlow; Sawyer, Helen B. (August 1927). "A Classification of Globular Clusters". Harvard College Observatory Bulletin. 849 (849): 11–14. Bibcode:1927BHarO.849...11S.

- ^ Levy 2005, pp. 157–158.

- ^ "Globular Cluster M15 and Planetary Nebula Pease 1". www.astropix.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18.

- ^ Dunlop, Storm (2005). Atlas of the Night Sky. Collins. ISBN 0-00-717223-0.

- ^ a b c Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects. Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

Cited texts[edit]

- Schlegel, Gustaaf (1967) [1875]. Uranographie Chinoise (in French). Taipei, Republic of China: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company.

- Staal, Julius (1988). The New Patterns in the Night Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars. Blacksburg: McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939923-10-6.

- Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

External links[edit]

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Pegasus

- The clickable Pegasus

- Star Tales – Pegasus

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (ca 160 medieval and early modern images of Pegasus)