Paulina Luisi

Paulina Luisi | |

|---|---|

Luisi in 1921 | |

| Born | Paulina Luisi Janicki 1875 |

| Died | 1950 (aged 74–75) |

| Occupation(s) | Physician, teacher, activist |

Paulina Luisi Janicki (1875–1950) was a leader of the feminist movement in Uruguay. In 1909, she became the first Uruguayan woman to earn a medical degree and was a firm advocate of sex education in the schools. She represented Uruguay in international women's conferences and traveled throughout Latin America and Europe. She was also the first Latin American woman to participate in the League of Nations and became one its most influential early activists. Her work has had a lasting effect on women of the Americas.

Biographical Information[edit]

Paulina Luisi was born in Argentina in 1875. Her mother, Maria Teresa Josefina Janicki, was of Polish descent and her father, Angel Luisi, was believed to be of Italian ancestry. Shortly after her birth, the family moved to Uruguay.[1] Luisi also had two sisters, Clotilde Luisi, who was the first female lawyer in Uruguay, and Luisa Luisi, who was a famous poet.[2]

The primary figures whom Luisi drew inspiration from and who provided her with undivided support were her parents. Maria encouraged Luisi to pursue her dreams despite the social constraints placed on women in the early twentieth century. Her father, Angel, an educator and socialist, instilled in her “an uncontainable desire for justice and liberty.” [1] Following her father, throughout her life, Luisi was a socialist interested in questions of moral reform.

Medical Education and Teaching[edit]

Luisi received a bachelor's degree in 1899 and graduated from the Medical School of the University of the Republic of Uruguay. In 1908 she became Uruguay's first female physician and surgeon. She became the head of the gynecology clinic of the Faculty of Medicine at the National University in Montevideo.[3] In 1907 there were only four female doctors and three-hundred and five male doctors in Uruguay. As more women joined the medical field, the number of women physicians started to rise.[4] Luisi wrote medical papers on topics ranging from prophylaxis of contiguous diseases, hygiene, eugenics, open air schools, hereditary qualities, and social diseases, to the "white slave trade," prostitution, venereal diseases, and mother's rights.

Sex-Health Education[edit]

In 1916 Luisi gave the keynote address before the First Pan-American Child Congress with an emphasis on sociology and education of women and children in Latin -America.[5] Controversially, in the speech. Luisi advocated obligatory sex-health education programs in the public school system from primary through secondary school, as well as women's right to vote.[6] She defined sex education as the pedagogic tool to teach the individual to subject sexual drives to the will of an instructed, conscientious, and responsible intellect.[7] Classes in sex education would emphasize the need for will power and self-discipline, regular moderate physical exercise to burn up sexual energy, and the desirability of avoiding sexually stimulating entertainments.[8] As opposed to sex education, health education classes would focus more on the scientific aspects of reproduction of the species, natural history, anatomy, personal hygiene, and the prevention of venereal diseases.[8] Due to these suggestions, Luisi was called an anarchist and a revolutionary. She was also accused of wanting to teach students how to become prostitutes. In 1944, her suggestions for sex-health education were finally incorporated into the Uruguayan public school system. Luisi believed that “man and woman are nothing but two forms of the same being, equipped only with the differences that the preservation of the species requires."[9] In her understanding, then, differences in anatomy did not dictate different roles for men and women. Luisi also worked as a teacher at the Teacher's Training College for Women and as an advocate for including hygiene among the subjects taught to future teachers. Her lectures and arguments were specifically designed to introduce prophylaxis as a subject within the teachers' training syllabus.

Feminist Influences[edit]

Josephine Butler, a famous 19th-century English moral reformer, had powerful influence on Luisi.[10] Her fight against the Contagious Disease Act of 1864, and her founding of the International Abolitionist Federation in Geneva, Switzerland to curb the white slave trade [11] served as a continual source of inspiration for Luisi.[12]

Luisi’s feminist ideas built upon other movements occurring in the early twentieth century. While Luisi was still a student, Argentine liberal feminist Petrona Eyle wrote to her in her capacity as president of the Universitarias Argentinas (Argentine Association of University Women, affiliated with the American Association of University Women (AAUW)), recruiting her to join the organization. In a letter dated May 1, 1907, Eyle encouraged Luisi and her female colleagues in the university to form a Uruguayan branch of the Universitarias, stating that “although there aren’t many of you now, you will always be the nucleus around which others will come together.” [13]

It appears that Luisi and others accepted this invitation and joined with their Argentine counterparts in 1907. Important also to Luisi’s insertion into Pan-American liberal feminist networks and to her propulsion to the leadership of Uruguayan liberal feminism was her participation in the Women's Congress (Congreso Femenino) held in Buenos Aires in 1910.[14] There she became acquainted with prominent Argentine feminists such as Alicia Moreau de Justo and Cecilia Gierson [15] Organized by the Universitarias, the conference brought together more than 200 women, representing Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, Paraguay, and Chile. It was likely at this conference that Luisi first came into contact with many of the leaders (or soon-to-be leaders) of liberal feminism in South America, and where she would establish ontacts and friendships that would endure for decades afterwards.[13] Trips to Europe brought her into contact with women such as Ghenia Avril de Saint Croix, president of the moral unity committee of the International Council of Women, and Julie Siegfried, president of the French National Council of Women.[16]

Feminist Activism in Uruguay and the Americas[edit]

Uruguayan Feminism[edit]

Prior to Luisi's feminist activism, there were no organized movements for women's rights in Uruguay, despite the country's progressive stance on social legislation in the early twentieth century.[1] As a Uruguayan representative at the First Pan-American Scientific Congress meeting in 1915, Luisi helped found a Pan-American Women's Auxiliary, which advocated for "social and economic betterment " of women and children.[1] After this experience, Luisi turned her attention to developing women’s organizations in her home country.

Luisi, together with Isabel Pinto de Vidal and Francisca Beretervide, founded the Consejo Nacional de Mujeres (CONAMU), a branch of the International Council of Women in Uruguay in 1916.[17] Luisi became the founder and primary editor of the CONAMU bulletin Acción Femenina (Feminine Action). The bulletin primarily focused on topics concerning women's values and equality. In the 1917 edition, Luisi published her definition of feminism stating the term implies "…that woman is something more than material created to serve and obey man like a slave, that she is more than a machine to produce children and care for the home; that women have feelings and intellect; that it is their mission to perpetuate the species and this must be done with more than the entrails and the breasts; it must be done with a mind and a heart prepared to be a mother and an educator; that she must be the man’s partner and counselor not his slave."[18] The CONAMU served as a place for women to empower each other, with Luisi at the forefront, and focused on social problems including women’s social welfare and education, working women’s conditions, alcoholism, and equal moral standards.[19]

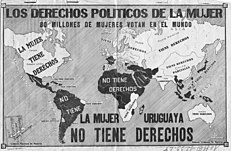

Luisi was a strong advocate for working women as well.[20] She created the two first female trade unions that existed in Uruguay – Unión de Telefonistas (Telephone Operators Union) and the Costureras de sastrerías (Seamstresses from Tailor's Shops). Luisi worked with the Telephone Workers Union to get better work conditions, and the women went from having to operate one hundred phones to eighty thanks to Luisi's involvement. Uruguayans warmed to the idea of women’s suffrage in the 1910s, and in 1919 Luisi founded the Alianza de Mujeres para los Derechos Femeninos (Women Alliance for Women's Rights), which was affiliated with the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. The Alianza pressured elected officials to enact women’s political rights.[21] The Alianza worked closely with deputy Alfeo Brum to get congress to pass a bill authorizing women’s vote at the municipal level, so that women could fulfill their "legitimate social duty of rendering service to the different domains of public welfare."[22] The bill did not pass. With suffrage stalled, four years after its creation the Alianza expanded its agenda to include women’s economic and civil rights.[23]

Pan-American Feminism[edit]

In addition to fighting for women’s rights in Uruguay, Luisi aspired to create a Pan-American feminist movement that would benefit countries in the Americas.[24] She also wanted to achieve equality globally. Luisi traveled to the United States with the hope of having American feminists help develop Pan-American feminism, but she emerged disappointed in American women’s disdain for South American feminists. It wasn't until World War II broke out that Luisi once again advocated for "sisterhood" between the US and Latin American feminists.[25] Luisi's activism was internationally recognized and popular in Latin America. In 1947, the Primer Congreso Interamericano de Mujeres (First Inter-American Women’s Conference) in Guatemala paid tribute to Luisi, recognizing her as the mother of inter-American feminism.[26]

Radio Femenina[edit]

Paulina Luisi's activism was also prevalent in public radio stations in Latin America. Radio Femenina, a radio station in Uruguay, was host to Luisi in the 1930s. On air, Luisi urged feminists to remain active because women were the only ones who could make a difference as mediators and peacemakers.[27] Luisi was very influential as the radio allowed her to speak her mind freely and reach places beyond Argentina and Uruguay. Luisi's radio personality placed her in a position of authority as an older wise women among the feminists.[28] A milestone within her radio involvement occurred in her later years when she encouraged women to vote in the 1942 elections in Uruguay to prove that women were worthy of their citizenship.[29] In her older age in the 1940s, Luisi became known as La Abuela, the grandmother, a nickname that displayed ideals of motherhood attached to feminism.

League of Nations Work on Sex Trafficking[edit]

Luisi acted as a Delegate of the Uruguayan Government to the League of Nations Commission for the Protection of Children and Youth, where she took up the fight against the illegal sex trade. She was also a member of the Technical Commission, and she was responsible of the examination of the women trade question.

One of Paulina Luisi's accomplishments as an activist was to end sex trafficking in women. Luisi's experience in the medical field, where she witnessed women having sexual health issues such as infections. This experience drove her to become involved in issues against prostitution.[30] Luisi viewed prostitution as an act degrading to all women, regardless of their nationalisty.[31] Prostitution was a growing issue in Latin America and around the world, and women were oftentimes forced into that lifestyle. Luisi viewed prostitution as product of economic hardship and saw the correlation between prostitution and low wages.[32]

Luisi's famous speech, "The White Slave Trade and the Problem of Reglementation" at the University of Buenos Aires in 1919 led to the creation of the Argentine-Uruguayan Abolitionist Committee.[33] Luisi's efforts were also seen in Argentina where she collaborated with the Municipal Council that created laws that would aid prostitutes who sought rehabilitation. The laws provided work opportunities, legal protection, and hostels.[33]

Commitment to sexual health also led to her involvement in the League of Nations through the Committee on the Traffic of Women and Children. The initial convention for the suppression of traffic reflects Luisi's influence.[34] In 1934, Luisi and the Uruguayan National Council of Women passed the Children's Code. The law provided protection of pregnant women, granted protection of children from birth, and tackled problems of illegitimacy.[35]

In Luisi's case, the main purpose of moral unity was to restrain the practice of prostitution, to check the spread of venereal disease, to protect the future of the human race, and to elevate motherhood from the realm of lust to that of progenitor and guardian of the species.[36]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Marino, Katherine M. (2019). Feminism for the Americas : the making of an international human rights movement. Chapel Hill. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4696-4969-6. OCLC 1043051115.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PhD Dissertation). Stanford: Stanford University. p. 38.

- ^ Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PhD Dissertation) (PDF). Stanford: Stanford Univeirty.

- ^ Lavrin, Asunción. (1995). Women, feminism, and social change in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, 1890-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-585-30067-4. OCLC 45729374.

- ^ Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PhD Dissertation) (PDF). Stanford: Stanford University. pp. iv.

- ^ Marino, Katherine M. (2019). Feminism for the Americas : the making of an international human rights movement. Chapel Hill. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4696-4969-6. OCLC 1043051115.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Luisi 1950: 82–83 in Little 1975: 394

- ^ a b Little 1975: 395

- ^ Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PhD Dissertation) (PDF). Stanford: Stanford.

- ^ Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PhD Dissertation) (PDF). Stanford: Stanford University. p. 41.

- ^ Chataway, 1962, in Little, 1975: 391

- ^ Luisi, 1948: 24–26, in Little 1975: 391

- ^ a b Ehrick, 410

- ^ Little 1975: 391

- ^ Drier, 1920 in Little 1975: 391

- ^ Acción Femenina, 1917: 134 in Little 1975, 391

- ^ Oldfield, Sybil (2003). International Woman Suffrage: October 1916-September 1918, Volume III. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 279. ISBN 0-415-25739-5.

- ^ Acción Femenina, 1917: 48 in Little 1975: 387

- ^ Lavrin, Asunción. (1995). Women, feminism, and social change in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, 1890-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 382–329. ISBN 0-585-30067-4. OCLC 45729374.

- ^ Ehrick, Christine (2005). The shield of the weak : feminism and the State in Uruguay, 1903-1933. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-3470-1. OCLC 780539383.

- ^ Marino, Katherine M. (2019). Feminism for the Americas : the making of an international human rights movement. Chapel Hill. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4696-4969-6. OCLC 1043051115.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ehrick, Christine (2005). The shield of the weak : feminism and the State in Uruguay, 1903-1933. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-8263-3470-1. OCLC 780539383.

- ^ Lavrin, Asunción. (1995). Women, feminism, and social change in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, 1890-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-585-30067-4. OCLC 45729374.

- ^ Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PhD Dissertation) (PDF). Stanford: Stanford University.

- ^ Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PhD Dissertation) (PDF). Stanford: Stanford University. p. 24.

- ^ Marino, Katherine (2019). Feminism for the Americas. University of North Carolina Press. p. 227.

- ^ Ehrick, Christine (2015). Radio and the Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay 1930-1950. Cambridge University Press. p. 107.

- ^ Ehrick, Christine (2015). Radio and the Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay 1930-1950. Cambridge University Press. p. 112.

- ^ Ehrick, Christine (2015). Radio and Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay 1930- 1950. Cambridge University Press. p. 113.

- ^ Little, Cynthia Jeffress (1975). "Moral Reform and Feminism: A Case Study". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 17 (4): 392. doi:10.2307/174949. JSTOR 174949.

- ^ Rodriguez Garcia, Magaly (August 29, 2012). "The League of Nations and the Moral Recruitment of Women". International Review of Social History. 20: 105.

- ^ Rodriguez Garcia, Magaly (29 August 2012). "The League of Nations and the Moral Recruitment of Women". International Review of Social History. 20: 123.

- ^ a b Little, Cynthia Jeffress (1975). "Moral Reform and Feminism: A Case Study". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 17 (4): 393. doi:10.2307/174949. JSTOR 174949.

- ^ Little, Cynthia Jeffress (1975). "Moral Reform and Feminism: A Case Study". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 17 (4): 394. doi:10.2307/174949. JSTOR 174949.

- ^ Little, Cynthia Jeffress (1975). "Moral Reform and Feminism: A Case Study". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 17 (4): 392. doi:10.2307/174949. JSTOR 174949.

- ^ Luisi, 1950: 30–31, 55–56; 1948: 37–39 in Little 1975: 391

References[edit]

- Ehrick, Christine. Gender & History, Nov 98, Vol. 10 Issue 3, pp. 406–410

- Little, Cynthia Jeffress, Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs, Vol. 17, No. 4, Special Issue: The Changing Role of Women in Latin America. (Nov., 1975), pp. 386–397.

- 1875 births

- 1930 deaths

- Uruguayan feminists

- Uruguayan suffragists

- Socialist feminists

- Argentine emigrants to Uruguay

- Uruguayan people of Italian descent

- Uruguayan people of Polish descent

- 20th-century Uruguayan women politicians

- 20th-century Uruguayan politicians

- 20th-century Uruguayan physicians

- Uruguayan women physicians

- Uruguayan gynaecologists