Nineteenth-century theatrical scenery

Theatre in the nineteenth century was noted for its changing philosophy from the Romanticism and Neoclassicism that dominated Europe since the late 18th century to Realism and Naturalism in the latter half of the 19th century before it eventually gave way to the rise of Modernism in the 20th century. Scenery in theater at the time closely mirrored these changes, and with the onset of the Industrial Revolution and technological advancement throughout the century, dramatically changed the aesthetics of the theater.

Realism[edit]

Theatrical realism was a general movement in 19th-century theatre from the time period of 1870-1960 that developed a set of dramatic and theatrical conventions with the aim of bringing a greater fidelity of real life to texts and performances. Part of a broader artistic movement, it included a focus on everyday middle-class drama, ordinary speech, and simple settings. This idea of representing subject matter truthfully, was evident in the changes that were made to scenic design in theater. Theatrical designers and directors began meticulously researching historical accuracy for their productions, which meant that scenery could no longer be drawn from stock - which was typically used over and over again in generic settings for different shows. Scenery began to be custom-designed and made for specific production. This meant, while scenery used to be seen as capital investment, it was now considered to be more disposable when the production was removed from the repertory.[1]

Scenic innovation[edit]

One of the most important scenic transitions into the 20th century was from the often-used two-dimensional scenic backdrop to three-dimensional sets. Previously, as a two-dimensional environment, scenery did not provide an embracing, physical environment for the dramatic action happening on stage. This changed when three-dimensional sets were introduced in the first half of the century. With this innovation, along with change in audience and stage dynamic as well as advancements in theater architecture that allowed for hidden scene changes, the theater became more representational instead of presentational, and invited the audience to be transported to a conceived 'other' world.[2]

Box set[edit]

The epitome of the new three-dimensional style sets and one of the most important advancements of scenic design was the popularization of the box set. The box set has been around since the 17th century, but lacked support.[3] Madame Vestris had introduced realistic stage furnishing in 1836 at her little Olympic Theatre in London, and forced them on American managers when she toured that country in 1838-1839.[4] The box set was a gradual replacement of the painted wing-and-shutter sets. Between 1800 and 1875, many theater artists began to use them. A box set consists of flats hinged together to represent a room; it often has practicable elements, such as doors and windows, which can be used during the course of a play or show.[5] With the new pursuit of realism, room-like box settings now had heavy molding, real doors with doorknobs, and ample accurate furniture. Having the box set also meant that many theater artists began to stage all the action behind the proscenium in the late 1800s, thus reinforcing the illusion of a fourth wall. Audiences would be watching a “slice of life” through a window. Box sets allowed scenic designers to create better visualized atmospheres and moods.

Aesthetic style[edit]

19th-century scenic styles in America were unique derivations from the European masters. Scenic artists from Europe brought with them the Romantic, Baroque, or classical landscapes that they knew from their homes, but the styles seemed to change when they landed on the American shore.[6] The romantic English landscape painting style slowly adapted to the American image. The more rugged wild-western American landscape came to be idealized by native scenic artists throughout the century. Many theatres invested in generic scenery meant for virtually any production. An all-purpose set included landscapes, European cities, prison, palace, village, mountain pass, and forest.[7]

The oleo was a versatile drop for any sort of entertainment. The oleo drop often hung in the in-one position, subdividing the stage into a shallower depth that was more appropriate for a brief interlude.[8] The act curtain or drop curtain functioned as today's main drape, the decorative divider wall between audience and stage. Often, it was the most elaborate piece a theater owned and was painted to harmonize with the interior decorations of the theater itself.

Technological advancement[edit]

During the nineteenth century, the technology of the Industrial Revolution was applied to theater. Many historians believe that the popularity of melodrama, with its emphasis on stage spectacle and special effects, accelerated these technological innovations: For example, Dion Boucicault was responsible for the introduction of fireproofing in the theater when one of his melodramatic plays called for an onstage fire.[9]

Panorama[edit]

While the invention of the panorama is attributed to Robert Barker in 1787, Louis Jacques Daguerre is largely seen as having perfected the invention in the 19th century. He created the diorama: a still painting viewed by an audience sitting on a rotating platform. This soon gave way to the moving panorama: a setting painted on a long cloth, which could be unrolled across the stage by turning spools, created an illusion of movement and changing locales. A popular American play, William Dunlap's A Trip to Niagara (1828), used this device to show a voyage from New York City to Niagara Falls via a steamboat.[10] The advent of the panoramas coupled with Charles Kean’s invention of the Corsican trap meant that entire horse and chariot races could be enacted on stage.[11] The emphasis on recreating natural environments onstage was probably influenced by romanticism, which called for a "return to nature."

Elevator stage[edit]

On February 7, 1880, the Spirit of the Times announced: "Tonight Mr. J. Steele MacKaye will open the most exquisite theatre in the world, and all New York will assemble to do honor to the realization of his artistic visions…Mr. MacKaye will play the drama Hazel Kirke through with only two-minute waits between the acts, and will then exhibit the double stage—one compartment set for the kitchen of Blackburn Mill and other as boudoir at Fairy Grove Villa." MacKaye’s elevator stage was an important development of American drama and theatre. It was a solution to the problem posed by the increasing use of box sets to reproduce interior scenes in detail. With the elevator stage, multiple scenes could be changed in a fast and detailed way. This greatly improved the speed and efficiency of scenic changes, and design didn’t have to be simplified; it could still be detailed. The elevator stage was described in Scientific American, April 5, 1884. "[It consists] of two theatrical stages, one above another, to be moved up and down as an elevator car is operated in a high building, and so that either one of them can easily and quickly be at any time brought to the proper level for acting thereon in front of the auditorium. While the play is proceeding before the audience, the assistants arrange another scene on the upper stage."[12]

Edwin Booth Theatre[edit]

New styles of scenery meant that new means of scene shifting were needed. Booth's Theatre, opened in 1869, was the first in a new generation of theaters built specifically to suit three-dimensional set pieces. It was the first theater to have a level stage floor (rather than a raked floor, as had been the standard in proscenium-arch theaters since the Renaissance) and no grooves in the stage floor for shifting flats. This idea would become the standard by the end of the century. Elevators and equipment for flying scenery also complemented the space.[13]

Stage lighting[edit]

Nineteenth-century technology revolutionized stage lighting, which until then had been primitive. The introduction of gas lighting was the first step. In 1816, Philadelphia's Chestnut Street Theater became the earliest gas-lit playhouse in the world.[14] The introduction of gas lighting revolutionized stage lighting. It provided a somewhat more natural and adequate light for the play and the scenic space upstage of the proscenium arch. However, this new richness in lighting provided difficulties at first. Though scenic painters had to learn to subdue their colors to the increased candle-power, the brightness only further highlighted the disparity between three-dimensional set pieces and their two-dimensional backdrop and led to the latter's eventual decline. The advent of limelight, also known as Drummond light, also effectively introduced spotlighting to theater.[15] Thomas Edison's electric incandescent lamp, invented in 1879, was the next step. It made electricity the most flexible, most controllable, and safest form of lighting; in the twentieth century, it would make stage lighting design a true art. These new means of illumination tremendously increased the control over stage light and stimulated interest in imitating lighting phenomena of nature.[16]

Noted designers, artists, and technologists[edit]

It was during this time that scenic artists began to be recognized for their work. Many of the scenic artists operated their own scenic studios in New York and towards the latter half of the century, the first theatrical unions were formed as a response to the Theatre Syndicate. Producers who originally hired staff carpenters and company painters began to place their productions out to bid. It was also during this time period that designers began working with models to convey their design.[17]

- Steele MacKaye (1842-1894) was an innovative theater technologist who invented the elevator stage. In 1880, at the Madison Square Theater in New York, MacKaye used two stages: one above the other, which could be raised and lowered; while one stage was in view of the audience, the scenery on the other, which was either in the basement or in the fly area, could be changed.[18]

- David Belasco (1853-1931) was an American producer, director and playwright. Mr. Belasco is primarily remembered today for his emphasis on naturalistic detail. David Belasco is best known for his ultra-realistic melodramas of the turn of the century. He and his chief scenic artist, George Gros, created meticulously detailed interiors, realistic exteriors, and stunning atmospheric effects.[19] Belasco and Gros produced some of the most memorable scenic inventions of the American theatre and certainly some of the finest realistic scenery of theatre history. His laborious scenic and lighting techniques were seen by the avant-garde as the embodiment of every ill of the stage and were severely ridiculed by history. In 1909, for a production of The Easiest Way, his scenic artist placed the contents of a boarding house room, including the wallpaper, on the stage of the Stuyvesant Theatre and three years later (1912) he built on stage a fully functioning restaurant for the Governor's Lady.[20]

- Alfred Roller (1864-1935) was trained as a painter in Vienna, but his designs hinted at a new concept of scenic design.[21] Focused entirely on the interplay of light and color to create evocative stage spaces. Roller’s designs relied on a selected or simplified realism in which only few items were introduced to the stage, but each of them evocative, detailed and powerful. He utilized mobile scenic towers that could be rearranged and altered with light to form new shapes and movement patterns on the stage (Sumner 338). He was probably the earliest designer to embody and practice the ideas of Adolph Appia and Edward Gordon Craig.

- Charles Witham (1842-1926) was born in Portland, Maine and educated as an artist. He spent some time as an itinerant landscapist before becoming involved with the theater. Thanks to the friendship of Gaspard Maeder, Witham obtained his first theatre job as Maeder's assistant when the latter was chief designer for Niblo’s Garden in New York in the early 1860s. By 1863, Witham had become head designer for the Boston Theater where he painted scenery for Edwin Forrest. His stay in Boston was short because he was hired by Edwin Booth to join his staff as scenic artist. He would go on to be Booth's primary designer for years to come. His work remains the largest surviving collection of theater scenic art from the time period.[22]

Notable plays[edit]

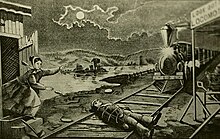

- Under the Gaslight (1867) was one of the first of many plays to use a steam engine onstage while the hero was being tied to the railway tracks. “Despite the fact that, on the first night, the machinery of the great railroad scene failed to work properly, the audience was held in tense excitement, and the play from the outset was a success”. It ran for 110 performances.[23] The mechanical effects involved are said to have been patented by Augustin Daly.

- There were many thrills in The Black Crook (1866), but the greatest of them was the corps de ballet and the hundreds of costumes. After the premier, which lasted from 7:45 pm till 1:15 am, the Tribune reported that “The Scenery is magnificent; the ballet is beautiful; the drama is—rubbish…the last scene in the play, however, will dazzle and impress to even a greater degree, by its lavish richness and barbaric splendor. All that gold and silver, and gems and light, and woman’s beauty can contribute to fascinate the eye and charm the sense.[24] The best exhibited scenery piece is the one that closes the second act: a vast grotto extending into an almost measureless perspective. Stalactites descend from the arched roof. A tranquil and lovely lake reflects the golden glories that span it like a vast sky. In every direction one sees the bright sheen or the dull richness of massy gold. Beautiful fairies and sprites make the scene luxuriant.[25]

- The Poor of New York (1899) scenically displayed such contrasts and spectacles as a rich home in Madison Square, a tenement house in Cross Street, with a fire, a bank in Nassau Street, and a snow storm in Union Square.[26]

Aftermath[edit]

The end of the 19th century witnessed both the height and the end of scenery painted in traditional perspective. Scenic design was realistic and creative, releasing the audience’s imagination. Realism was but a passing style. Towards the end of the century, realism would find an opposite in naturalism. Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig would be the ones to revolt against the idea of the actor standing on a flat floor surrounded by “realistic” painted canvases. Their controversial ideas would be the basis of the New Stagecraft. The 20th century would bring the scenic designer an entirely new aesthetic for the world of the theatre in the form of Henrik Ibsen and Modernism. As movies replaced theatre’s popularity, an international aesthetic weighed in against painted scenery, scenic studios began to shrink, and scenic artists began to disappear. The golden age of scenic painting of the 19th century rapidly turned to a much more fragmented one in the 20th century, as theatre styles changed radically and eventually the theatre lost popularity to movies and television.

References[edit]

- ^ Baugh, Christopher (2005). Theatre, Performance and Technology. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–33.

- ^ Baugh, Christopher (2005). Theatre, Performance and Technology. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–33.

- ^ Brockett, Oscar; Mitchell, Margaret; Hardberger, Linda (2010). Making the Scene: A History of Stage Design and Technology in Europe and the United States. San Antonio, TX: Tobin Theatre Arts Fund. pp. 157–222.

- ^ Taubman, Howard. The making of American theatre. New York: Coward McCann Inc., 196, pg 140

- ^ Martin, Ben. Theater in the Nineteenth Century. <http://homepage.smc.edu/martin_ben/TheaterHistory/nineteenth.htm>.

- ^ Beuder, Susan Crabtree & Peter. Scenic Art for the Theatre: History, Tools, and Techniques. Ed. Taylor & Francis. Illustrated. 2005.

- ^ Beuder, Susan Crabtree & Peter. Scenic Art for the Theatre: History, Tools, and Techniques. Ed. Taylor & Francis. Illustrated. 2005, pg 415

- ^ Beuder, Susan Crabtree & Peter. Scenic Art for the Theatre: History, Tools, and Techniques. Ed. Taylor & Francis. Illustrated. 2005, pg 415

- ^ Martin, Ben. Theater in the Nineteenth Century. <http://homepage.smc.edu/martin_ben/TheaterHistory/nineteenth.htm>

- ^ Martin, Ben. Theater in the Nineteenth Century. <http://homepage.smc.edu/martin_ben/TheaterHistory/nineteenth.htm>.

- ^ Watson, Jack; Fletcher Kernie, Grant (1993). A Cultural History of Theatre. New York: Longman. pp. 288–327.

- ^ French, Glenn Hughes & Samuel. A history of the American theatre. Binghamton: Vail Ballot Press Inc., 1951, pp. 234-236

- ^ Brockett, Oscar; Mitchell, Margaret; Hardberger, Linda (2010). Making the Scene: A History of Stage Design and Technology in Europe and the United States. San Antonio, TX: Tobin Theatre Arts Fund. pp. 157–222.

- ^ Hewitt, Barnard. Theatre U.S.A. 1665-1957. University of Illinois: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1959, pg 105

- ^ Watson, Jack; Fletcher Kernie, Grant (1993). A Cultural History of Theatre. New York: Longman. pp. 288–327.

- ^ Hewitt, Barnard. Theatre U.S.A. 1665-1957. University of Illinois: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1959, pg 105.

- ^ Larson, Orville (1989). Scene Design in the American Theatre from 1915 to 1960. Fayetteville: U of Arkansas. pp. 3–30.

- ^ Hewitt, Barnard. Theatre U.S.A. 1665-1957. University of Illinois: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1959.

- ^ Beuder, Susan Crabtree & Peter. Scenic Art for the Theatre: History, Tools, and Techniques. Ed. Taylor & Francis. Illustrated. 2005, pg.415

- ^ Wild, Larry. A Brief History of Theatrical Scenery. 18 February 2002. 23 February 2006 <http://www3.northern.edu/wild/ScDes/sdhist.htm>.

- ^ Sumner, Edwin Mims Jr. & Oral. The Pageant of America- the American stage. Yale University Press, 1929, pg 338

- ^ Larson, Orville (1989). Scene Design in the American Theatre from 1915 to 1960. Fayetteville: U of Arkansas. pp. 3–30.

- ^ French, Glenn Hughes & Samuel. A history of the American theatre. Binghamton: Vail Ballot Press Inc., 1951, pg 198.

- ^ French, Glenn Hughes & Samuel. A history of the American theatre. Binghamton: Vail Ballot Press Inc., 1951, pg 199

- ^ Hewitt, Barnard. Theatre U.S.A. 1665-1957. University of Illinois: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1959, pg 196.

- ^ French, Glenn Hughes & Samuel. A history of the American theatre. Binghamton: Vail Ballot Press Inc., 1951, pg 187,

Beudert, Susan Crabtree & Peter. Scenic Art for the Theatre: History, Tools, and Techniques. Ed. Taylor & Francis. Illustrated. 2005.