Manhattan Transfer station

Manhattan Transfer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

circa 1911 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Northeast Corridor Harrison, New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°44′31″N 74°08′38″W / 40.742°N 74.144°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by | PRR & H&M | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line(s) | PRR main line Park Place – Hudson Terminal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1910 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | June 20, 1937 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrified | (DC) Third Rail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

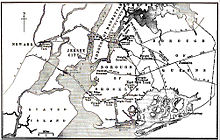

Manhattan Transfer was a passenger transfer station in Harrison, New Jersey, east of Newark, 8.8 miles (14.2 km) west of New York Penn Station on the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) main line, now Amtrak's Northeast Corridor. It operated from 1910 to 1937 and consisted of two 1,100 feet (340 m) car-floor-level platforms, one on each side of the PRR line. It was also served by the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad. There were no pedestrian entrances or exits to the station, as its sole purpose was for passengers to change trains, or for trains to have their locomotives changed.

History[edit]

Need and operation[edit]

Until 1910, none of the railroads that crossed New Jersey to reach New York City crossed the Hudson River. Instead, passengers rode to terminals on the Hudson Waterfront, where they boarded ferries. The dominant Pennsylvania Railroad was no exception; its passenger trains ran to Exchange Place in Jersey City.[2]

On November 27, 1910, the PRR opened the New York Tunnel Extension, a line that ran through a pair of tunnels under the Hudson River to New York Penn Station. This new line branched off the original line two miles east of Newark, then ran northeast across the Jersey Meadows to the tunnels.[3] Just west of the split, the PRR built the Manhattan Transfer station.[4] Passenger trains bound for New York Penn paused there so that their steam locomotives could be replaced by electric locomotives that could run through the tunnel under the river.[5] The station also allowed passengers to change trains; riders on the main line could transfer to local trains to Exchange Place, where they could catch ferries or Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (H&M) subway trains to 33rd Street Terminal in Manhattan, and riders from Exchange Place could change to PRR main line trains.[3]

The H&M, the precursor to the PATH train, started running trains between Hudson Terminal in Manhattan and Park Place in Newark on October 1, 1911.[6][7] H&M trains stopped at Exchange Place, Grove Street, Summit Avenue, Manhattan Transfer, and Harrison.[8] Afterward, H&M trains stopped on the outer tracks of the two Manhattan Transfer platforms, allowing passengers to transfer from Penn-Station-bound trains.[9] H&M trains also carried mail bound for PRR trains, retrieving first-class letters sent from the Church Street Station Post Office, near Hudson Terminal, and transferring the letters to PRR trains at Manhattan Transfer.[10]

The H&M ordered MP-38 railcars to run this special service, in partnership with the PRR. The "McAdoo Reds", as the MP-38s were called, ran only between Manhattan Transfer and New York City,[5][7] carrying the logos of PRR and H&M to show their partnership.[8] Until 1922 the PRR also operated a shuttle service from Manhattan Transfer to New York Penn, using six converted MP-54 cars.[11]

A spate of serious accidents involving H&M trains took place at Manhattan Transfer in the 1920s. A collision between two PRR trains occurred at Manhattan Transfer on October 27, 1921, injuring 36 people. The cause was heavy fog covering a train signal.[12] Less than a year later, on August 31, 1922, heavy fog caused another collision. This time, the collision was between two H&M trains; fifty people were injured, including eight who were seriously injured.[13] Another collision between two H&M trains near the station on July 22, 1923, killed one person and injured 15 others.[14] A crash between two PRR trains occurred at the station on February 24, 1925, killing 3 and injuring 32 more.[15]

Decline[edit]

Manhattan Transfer was built mainly because PRR trains needed to switch to electric locomotives. In 1913 the PRR's board voted to electrify its main line in the Philadelphia area using an 11 kV overhead catenary system.[16] This had to do with the PRR's cumbersome operations at Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, where trains had to enter and leave the terminal from the same side, and congestion frequently arose because of the length of time needed for steam locomotives to switch directions.[17] Tracks at Manhattan Transfer were originally electrified with 650 V third rail, which was used by PRR electric trains to Penn Station and Exchange Place, and by H&M trains between Park Place and Hudson Terminal.[18]

In 1928 the PRR and the Newark government agreed to build a new Newark Penn Station to replace three stations: Manhattan Transfer, Park Place, and the PRR's Market Street station in Newark. Newark Penn was to be a quarter-mile south of Park Place.[19] The H&M would be extended to Newark Penn via new approach tracks over the Passaic River, and H&M and PRR passengers would be able to connect at Newark Penn instead of Manhattan Transfer.[20]

Contracts to electrify the PRR tracks south of Manhattan Transfer with 11 kV overhead wires were awarded in 1929.[21] Two years later, in light of low interest rates and high unemployment, the PRR's president announced plans to speed up the electrification project, with plans to complete it in two and a half years instead of four.[22] In addition, new approach tracks to Newark Penn would be built over the Passaic River.[23] PRR trains to Exchange Place started using the 11 kV catenary system in December 1932.[18] Within two months, the PRR had completed the electrification of the main line from Philadelphia north to New York Penn Station; south to the PRR station in Wilmington, Delaware; and west to the Paoli, Pennsylvania, PRR station. By March 1933 most PRR trains on that stretch of the main line were pulled by electric engines, but PRR trains continued to stop at Manhattan Transfer for the H&M connection.[24] (The branch to South Amboy remained steam for a couple more years, so a few engine changes continued at Manhattan Transfer.) Around 1940 the third rail west of the west end of the tunnels was removed.[25]

On June 20, 1937 the H&M moved from Park Place to Newark Penn Station, and Manhattan Transfer and Park Place closed.[26][27] Newark Penn allowed transfers between the H&M, the PRR, and the newly extended Newark City Subway, and had exits to the street.[24] Manhattan Transfer was demolished, but the site of the platforms could be seen through the 1960s. The site of the eastbound platform was partly replaced by a yard for the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ) in 1967. After the opening of the Aldene Connection, the CNJ started running trains to PRR's Newark Penn Station, and the CNJ stored its trains in the yard on the eastbound platform's site.[28]

Manhattan Transfer became famous, and the name was used in other contexts. In 1925 John Dos Passos published an acclaimed novel about the busyness of New York City.[29][30][17] The tributes to Manhattan Transfer station include a jazz vocal ensemble formed in 1969.

Layout[edit]

Manhattan Transfer station consisted of two island platforms, one for westbound trains and one for eastbound. Each platform was 1,100 feet (340 m) long and 28 feet (8.5 m) wide. The station itself had four tracks, but several bypass tracks surrounded the station to south and north, and passed between the two platforms. H&M trains stopped on the outer tracks, while PRR trains stopped on the inner tracks.[2] The two platforms were brick, which deteriorated during later years.[31]

West of the station the H&M tracks split to the northwest and entered a viaduct, stopping at Harrison before terminating at Park Place station in Newark. PRR trains continued southwest[6] East of the station, the PRR tracks split to the northeast and continued 8 miles (13 km) to New York Penn, while the H&M tracks split to the southeast for 7 miles (11 km) to Exchange Place before entering the Downtown Hudson Tubes to Hudson Terminal in New York City.[6] There were two switch towers near the station: Tower N to the west and Tower S to the east.[7]

A sign box was above each platform, each containing around twenty signs, showing common destinations, as well as "named" trains. Before the arrival of the next train, a platform attendant would use a long pole to change the signs displayed.[11]

The only access to the station was by train, with no access to the surrounding area.[6][32][33] It was estimated that 230 million passengers had used Manhattan Transfer during its 27 years in operation.[31]

See also[edit]

- Susquehanna Transfer station (1939–1966)

- Secaucus Junction

References[edit]

- ^ Cudahy 2002, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 41.

- ^ a b "Pennsylvania Opens Its Great Station; First Regular Train Sent Through the Hudson River Tunnel at Midnight". The New York Times. November 27, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Open Pennsylvania Station To-night". The New York Times. November 26, 1910. p. 5. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d Cudahy 2002, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Chiasson, George (August 2015). "Rails Under the Hudson Revisited - The Hudson and Manhattan". Electric Railroaders' Association Bulletin: 7. Retrieved April 10, 2018 – via Issuu.

- ^ a b "TUBE SERVICE TO NEWARK.; Pennsylvania-Hudson Steel Trains in Operation This Morning". The New York Times. November 26, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Improved Transit Facilities by Newark High Speed Line" (PDF). The New York Times. October 1, 1911. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ "NEW MAIL PLAN SAVES TIME.; Letters Will Be Sent from Downtown to Manhattan Transfer Station". The New York Times. November 17, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 47.

- ^ "HAYS RECOVERING AFTER RAIL CRASH; Postmaster General Expects to Leave Today for the Capital-- One Woman Badly Hurt. FOG HID A SIGNAL LIGHT Thirty-Six Injured When Washington Express Rammed Local atManhattan Transfer". The New York Times. October 29, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "TUBE TRAINS CRASH IN FOG; 50 ARE HURT; Motorman of Rear Train Charged With Exceeding Rule as to Speed. HURT TOO BADLY TO TALK Eight Victims Seriously Injured, Some May Have Fractured Skulls.TWO INQUIRIES ARE BEGUNSteel Cars Prevent Loss of Life inAccident in New Jersey Meadows. First Train Halted. Motorman Unable to Talk. President Root's Statement". The New York Times. September 1, 1922. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "1 KILLED, 15 INJURED IN TUBE TRAIN CRASH; Boy, Standing at Front of Car, Crushed in Collision Near Manhattan Transfer. OTHERS SERIOUSLY HURT Motorman Tells Police That His Brakes Failed to Work Properly". The New York Times. July 12, 1923. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "3 KILLED, 32 INJURED IN TRAIN COLLISION ON JERSEY MEADOWS; Pennsylvania Local Speeds Into Atlantic Coast Express at Manhattan Transfer. DINING CAR TELESCOPED Motorman and His Helper Leap to Safety Just Before the Collision. CAR INSPECTORS KILLED Negro Cook Crushed to Death as He Shouts a Warning -- Responsibility Not Fixed. 3 KILLED, 32 INJURED IN TRAIN COLLISION". The New York Times. February 25, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Philadelphia Electric or Lehigh Navigation Likely to Secure Big Power Contracts From Pennsylvania Railroad" (PDF). Philadelphia Inquirer. March 13, 1913. p. 15. Retrieved April 10, 2018 – via fultonhistory.com.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 52.

- ^ "Newark to Get $20,000,000 Railroad Station; Manhattan Transfer Will Be Abolished". The New York Times. April 13, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "NEW NEWARK STATION TO COST $25,000,000; Raymond Announces Terms of Contract Which Will Abolish Manhattan Transfer". The New York Times. May 10, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "P.R.R. AWARDS CONTRACT.; Will Electrify Line From Manhattan Transfer to New Brunswick". The New York Times. October 8, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Railroad Speeds Electrification Program" :Improvements originally scheduled for next four years will be completed by 1933, according to announcement by President Atterbury. Plans involve expenditure of $175,000,000, Electric Railway Journal, March 1931, pg. 125-127, https://archive.org/stream/electricrailwayj75mcgrrich/electricrailwayj75mcgrrich_djvu.txt

- ^ "PENNSYLVANIA LINES SPEED CONSTRUCTION; TO SPEND $175,000,000; Atterbury Announces Decision to Rush Electrification, New Stations and Other Work. REDUCES 4-YEAR ESTIMATE Says Program Will Be Pushed to Completion in Two and a Half Years. SEES EMPLOYMENT AIDED Declares Conditions of Labor and Finance Are Favorable Now for Expansion. Mr. Atterbury's Statement. Lists Rail Projects. ATTERBURY PUSHES VAST RAIL PROGRAM Optimistic for Future". The New York Times. February 18, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 51.

- ^ "New Station Open for Hudson Tubes". The New York Times. June 20, 1937. p. 35. ProQuest 102085195. Retrieved March 30, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "OLD MANHATTAN TRANSFER GOES" (PDF). The Daily Argus. Mount Vernon, NY: Associated Press. June 19, 1937. p. 2. Retrieved April 11, 2018 – via fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Desmond Harding (June 1, 2004). Writing the City: Urban Visions and Literary Modernism. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-135-94747-7.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (August 30, 2003). "A Second Act for Dos Passos And His Panoramic Writings". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 48.

- ^ E.B., Temple (September 1910), The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad Meadows Division and Harrison Transfer Yard., Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, Vol. LXVIII, Paper No. 1153, American Society of Civil Engineers

- ^ "New High-Speed Line for Newark; Being Built by Pennsylvania Railroad and Hudson & Manhattan Company" (PDF). New York Times. April 2, 1911.

- Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- Former railway stations in New Jersey

- Demolished railway stations in the United States

- Harrison, New Jersey

- PATH stations in New Jersey

- Railway stations in Hudson County, New Jersey

- Railway stations in the United States opened in 1910

- Railway stations closed in 1937

- Former Pennsylvania Railroad stations

- Former Lehigh Valley Railroad stations

- Railway stations accessible only by rail

- Railway stations in the United States closed in the 1930s