Long poem

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The long poem is a literary genre including all poetry of considerable length. Though the definition of a long poem is vague and broad, the genre includes some of the most important poetry ever written.

With more than 220,000 (100,000 shloka or couplets) verses and about 1.8 million words in total, the Mahābhārata is one of the longest epic poems in the world.[1] It is roughly ten times the size of the Iliad and Odyssey combined, roughly five times longer than Dante's Divine Comedy, and about four times the size of the Ramayana and Ferdowsi's Shahnameh.

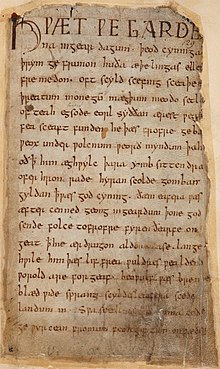

In English, Beowulf and Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde are among the first important long poems. The long poem thrived and gained new vitality in the hands of experimental Modernists in the early 1900s and has continued to evolve through the 21st century.

The long poem has evolved into an umbrella term, encompassing many subgenres, including epic, verse novel, verse narrative, lyric sequence, lyric series, and collage/montage.

Definitions[edit]

Length and meaning[edit]

Lynn Keller describes the long poem as being a poem that is simply "book-length," but perhaps the simplest way to define "long poem" is this: a long poem is long enough that its bulk carries meaning. Susan Stanford Friedman describes the long poem as a genre in which all poems that are not considered to be short can be considered apart. These overly inclusive definitions, though problematic, serve the breadth of the long poem, and have fueled its adaptation as a voice for cultural identity among marginalized persons in Modern and Contemporary poetry. Only a broad definition can apply to the genre as a whole. In general, a poem is a "long poem" when its length enhances and expands upon the thematic, creative, and formal weight of the poem.

Though the term "long poem" may be elusive to define, the term is now finally getting the attention it deserves. The genre has gained importance both as a literary form and as a means of collective expression. Lynn Keller solidifies the genre's importance in her essay, "Pushing the Limits," by stating that the long poem will always be recognized as a notable genre of importance in the early twentieth-century American literature.[2]

Purposes[edit]

Tale of the tribe[edit]

A long poem often functions to tell a "tale of the tribe," or a story that encompasses a whole culture's values and history. Ezra Pound coined the phrase, referring to his own long poem The Cantos. The long poem's length and scope can contain concerns of a magnitude that a shorter poem cannot address. The poet may see himself or herself as the "bearer of the light," to use Langston Hughes' term, who leads the journey through a culture's story, or as the one who makes known the light already within the tribe. The poet may also serve as a poet-prophet with special insight for their own tribe.

In Modern and Contemporary long poems the "tale of the tribe" has frequently been retold by culturally, economically, and socially marginalized persons. Thus, pseudo-epic narratives, such as Derek Walcott's "Omeros," have emerged to occupy voids where post-colonial persons, racially oppressed persons, women, and other people who have been ignored by classic epics, and denied a voice in the prestigious genre.

Revisionary mythopoesis[edit]

Various poets have undertaken a "revisionary mythopoesis" in the long poem genre. Since the genre has roots in forms that traditionally exclude poets who have minimal cultural authority, the long poem can be a "fundamental revision," and function as a discourse for those poets (Friedman). These "re-visions" may include neglected characters, deflation of traditionally celebrated characters, and a general reworking of standards set by the literary tradition. This revision is noted especially by feminist critical work that analyzes how women are given a new voice and story through the transformation of a previously "masculine" form.

Cultural commentary[edit]

Lynn Keller notes that the long poem enabled modernists to include sociological, anthropological, and historical material. Many long poems deal with history not in the revisionary sense but as a simple re-telling in order to prove a point. Then there are those who go a step further and recite a place's or people's history in order to teach. Like revisionary mythopoesis, they may attempt to make a point or demonstrate a new perspective by exaggerating or editing certain parts of history.

Concerns and controversies[edit]

Fears of the writer[edit]

Long poem authors sometimes find great difficulty in making the entire poem coherent and/or deciding on a way to end it or wrap it up. Fear of failure is also a common concern, that perhaps the poem will not have as great an impact as intended. Since many long poems take the author's lifetime to complete, this concern is especially troubling to anyone who attempts the long poem. Ezra Pound is an example of this dilemma, with his poem The Cantos.[3] As the long poem's roots lie in the epic, authors of the long poem often feel an intense pressure to make their long poems the defining literature of the national identity or the shared identity of a large group of people. The American long poem is under pressure from its European predecessors, revealing a special variety of this anxiety. Walt Whitman achieved this idea of characterizing the American identity in Song of Myself. Thus, when the author feels that their work fails to reach such a caliber or catalyze a change within the intended audience, they might consider the poem a failure as a whole.

Poets attempting to write a long poem often struggle to find the right form or combination of forms to use. Since the long poem itself cannot be strictly defined by one certain form, a challenge lies in choosing the most effective form.[4]

Generic conundrums[edit]

Lyric intensity[edit]

Some critics, most emphatically Edgar Allan Poe, consider poetry as a whole to be more closely tied to the lyric. They complain that the emotional intensity involved within a lyric is impossible to maintain in the length of the long poem, thus rendering the long poem impossible or inherently a failure.[5]

In his article "The long poem: sequence or consequence?" Ted Weiss quotes a passage from M. L. Rozenthal and Sally M. Gall's "The Modern Poetic Sequence" inspired by Poe's sentiments, "What we term a long poem is, in fact, merely a succession of brief ones.... It is needless to demonstrate that a poem is such, only inasmuch as it intensely excites, by elevating, the soul; and all intense excitements are, through a psychal-necessity, brief. For this reason, at least one half of the Paradise Lost is essentially prose—a succession of poetical excitements interspersed, inevitably, with corresponding depressions—the whole being deprived, through the extremities of its length, of the vastly important artistic element, totality, or unity, of effect. In short, a poem to be truly a poem should not exceed a half hour's reading. In any case, no unified long poem is possible."[6]

Naming and subgenres[edit]

Critic Lynn Keller also expresses concerns about the genre in her essay "Pushing the Limits". Keller states that because of the debate over and prevalence of subgenres and forms within the overarching genre of long poem, critics and readers tend to choose one subgenre, typically the epic form, as being the "authentic" representative form of the genre. Therefore, this causes the other equally important subgenres to be subject to criticism for not adhering to the more "authentic" form of long poem.[7] Other critics of the long poem sometimes hold the belief that with long poems, there is no "middle ground." They view long poems as ultimately being either epics or lyrics.[citation needed]

Many critics refer to the long poem by various adjective-filled subgenre names that often are made of various components found within the poem. These can lead to confusion about what a long poem is exactly. Below you will find a list describing the most common (and agreed upon) subgenre categories.[3]

Advantages of the genre[edit]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) |

The long poem genre has several advantages over prose and strictly lyric poetry. The most obvious difference between the long poem and other literary genres is the sheer difficulty of composing a long work entirely in verse. Poets who undertake the long poem face the serious problem of creating a work that is consistently poetic, sometimes taking strict forms and carrying them through the whole poem. However, the poets who do choose the long poem turn this liability into an advantage—if a poet can write a long poem, they prove themselves to be worthy. The very difficulty gives the genre an implicit prestige. Long poems have been among the most influential texts in the world since Homer. By writing a long poem, a poet participates in this tradition and must prove their virtuosity by living up to the tradition. As discussed below, the traditionally difficult long poem's prestige can be revised to serve radical purposes.

Additional benefits of the long poem:

- The long poem provides the artist with a greater space to create great meaning.

- A long poem allows the author to be encyclopedic in their treatment of the world, as opposed to the potentially narrow focus of the lyric.

- A long poem poet can work on a long poem their entire life, weaving in their impressions gleaned from the span of several generations (and historical events); it can be an ongoing work.

- A long poem can encapsulate not just traditional poetry, but incorporate dialogue, prose passages, and even scripting.

- A reader can absorb an entire world view from a long poem.

Female authors in the genre[edit]

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one of the first female authors of the modern era to attempt an epic poem .[citation needed] In her article "Written in blood: the art of mothering epic in the poetry of Elizabeth Barrett Browning", Olivia Gatti Taylor explores Browning's attempt to write an authentically feminine epic poem titled Aurora Leigh. Taylor posits that Browning began this process with the structure of her poem, "While earlier epics like the Aeneid and Paradise Lost have twelve books, Aurora Leigh was conceived as a nine-book epic; thus, the very structure of the work reveals its gestational nature. According to Sandra Donaldson, Barrett Browning's own experience at age forty-three of "giving birth and nurturing a child" greatly influenced her poetry "for the better", deepening her "sensitivity".

Genealogy[edit]

The most important "parent genre" to the long poem is the epic. An epic is a lengthy, revered narrative poem, ordinarily concerning a serious subject containing details of heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation. The term "long poem" includes all the generic expectations of epic and the reactions against those expectations. Many long poem subgenres share characteristics with the epic, including: telling the tale of a tribe or a nation, quests, history (either recitation or re-telling in order to learn from the past), a hero figure, or prophecies.

Other subgenres of the long poem include lyric sequence, series, collage, and verse-novel. What unites each of these subgenres under the heading of long poem is that their length has importance in their meaning. Each subgenre, however, is unique in its style, manner of composition, voice, narration, and proximity to outside genres.

Sequence poetry uses the chronological linking of poems to construct meaning, as each lyric builds on the poems previous to it. Examples include Louise Glück's The Wild Iris, and older sonnet cycles, such as Sir Philip Sidney's Astrophel and Stella or Dante's Vita Nuova. Serial lyrics similarly depend on the juxtaposition and dialogue between individual lyrics to build a greater depth of meaning.

Often, these subgenres are blended, blurred or overlapped to create second-generation subgenres. The blurring between the lines of the subgenres is what makes the long poem so hard to define, but it also marks the growing creativity in the use of the form.

Subgenres[edit]

Epic[edit]

Critic Joseph Conte describes the epic as a long poem that "has to have grand voice and purpose. . . it has to say something big."[8] Lynn Keller describes one of the epic's aspects as including a "quasi-circular quest-journey structure" that she says is present in the long poem Song of Myself by Whitman. Yet that long poem, Keller notes, does not have a "specified end toward which the poem or speaker is directed," unlike a more traditional long poem. Though long poems do have roots in the epic form, that does not mean long poems that are epic-like are completely epic. A second example of long poems distancing themselves from the traditional epic form is seen in Helen In Egypt by H.D. Though traditional epics feature physical quests or journeys, Helen In Egypt is about the psychological journey of Helen.

Other characteristics of the epic include a hero figure, myths, and quests for the characters. Many such characteristics are seen in various long poems, but with some changes. For example, Helen In Egypt brings mythic revision, or revisionary mythopoesis, into play. Even though it includes the myth from the epic, the revised telling of the myth makes the long poem stand out as its own form. Additionally, one cannot look at the epic as a single, unified form of inspiration for long poems. As Keller points out, certain long poems can have roots in very specific epics instead of the overall epic category.

The long poem Omeros by Derek Walcott has drawn mixed criticism on whether it should or should not be tied to the traditional epic form. Those against that idea say that the poem's story is not as important as those found in traditional epics. Omeros tells the tale of fishermen in the Caribbean fighting over and lusting after a waitress instead of a typically heroic tale of battles and quests. On the other side of the argument lies the point that it is important to keep in mind that Omeros has ties to the epic genre, if only as a contrast. By putting more simple characters in the forefront as opposed to warriors, Walcott revises the traditional epic form, which these critics say is something to notice as opposed to cutting off Omeros from any ties to the epic whatsoever. Furthermore, these critics say that one cannot ignore the epic influence on the poem since its characters' names are taken from Homer. In Omeros there are distinct elements obviously influenced by traditional epics, such as a trip to the underworld, talk of a muse, etc.

In interviews, Walcott has both affirmed and denied that Omeros is tied to the epic form. In one interview he stated that it was a type of epic poem, but in another interview he said the opposite, stating as part of his evidence that there are no epic-like battles in his poem. In Omeros Walcott implies that he has never read Homer, which is probably untrue based on the character names derived from Homer. Walcott's denial of his poem being tied too heavily to the epic form may stem from his concern that people might only think of it as being an epic-influenced poem instead of transcending the epic genre.

Based on this criticism of Omeros it is clear that the generic identity of a long poem greatly contributes to its meaning. Because long poems are influenced by many more strictly defined genres, a long poem revising strict generic rules creates striking contrast with epic-genre expectations.

Keller also notes that she agrees with critic Susan Friedman when Friedman expresses her concern that the long poem associated with the epic has been "the quintessential male territory whose boundaries enforce women's status as outsiders on the landscape of poetry." Considering that there are many long poem authors that are women, one cannot fully associate the long poem with the epic genre.

However, the typical exclusion of women in the epic tradition is for many female authors what makes the long poem an appealing form for laying cultural claim to the epic.

Control of or at least inclusion in the creation of a cultural epic is important because the traditional epic poem like The Odyssey or Virgil’s Aeneid is, at its core, a written history. Written history defines the good and the bad of a culture, the winners and losers, and the author of that history controls the very future by manipulating the knowledge of later generations. For Friedman to deny epic associations to the long poem because they are sometimes written by women is to counter the efforts of many female long poets.

If the long poem is considered an epic or invokes an epic in its length as many critics and readers aver then breaching its traditional exclusivity by using the epic to tell the story of marginalized peoples such as women rather than the victors is essentially an opportunity for the poet to rewrite history. Walcott’s Omeros is an excellent example of a long poem recording the untold history of a marginalized people.

Likewise H.D.’s revision of the story of Helen of Troy in Helen is an attempt to exonerate women from the blame of the Trojan War. In this sense, form inexorably serves the function and meaning of the poem by indicating to the reader that the poem is, if not an epic, epic-like and therefore a history. For some female authors using the well known form of an epic is a way to legitimize their stories, but by slightly altering the epic tradition they also indicate that the traditional way is unacceptable and insufficient for their purposes. Embodying the modernist dilemma, the long poem as epic often contains the seeming belief in the futility of tradition and history paired with the obvious dependence on them.

Lyric sequence[edit]

A lyric sequence is a collection of shorter lyric poems that interact to create a coherent, larger meaning. The lyric sequence often includes poems unified by a theme. A defining characteristic of this subgenre is that each lyric enhances the meaning of the other lyrics in the work, creating an enhanced collective metaphor, that opens the lyric sequence to unique adaptations of dialogue and other narrative/theatrical characteristics.

Critic Lynn Keller lends some insight to the lyric sequence by placing it in opposition to the epic: “At the opposite end of the critical spectrum are the treatments of the long poem that do not consider issues of quest, hero, community, nation, history and the like, and instead regard the form as essentially lyric.

Lyric series[edit]

The lyric series is a genre of poetry in which the seriality of short (but connective) lyric poems enhances the long poem's meaning. Seriality may contribute narrative coherence or thematic development, and it is often read in terms of the poem's productive process, i.e. how the poem "produces its own experience"(Shoptaw). Each lyric poem is distinct and has meaning in itself, yet it functions as an integral part of the series, giving it a greater meaning as within the long poem as well.

Deborah Sinnreich-Levi and Ian Laurie examine the work of Oton de Grandson in the lyric series, or "ballad series" form. Grandson wrote several sets of short love lyrics, using the series form for narrative coherence and thematic construction, as well as to examine different aspects of a single narrative. George Oppen's Discrete Series relates its poetic seriality to the mathematic concept of a discrete series. Langston Hughes' Montage of a Dream Deferred qualifies as a serial lyric as well as a montage.

Collage/montage[edit]

The best-known and most highly regarded example of a collage long poem is T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Critic Philip Cohen describes Eliot's use of the collage in his article "The Waste Land, 1921: Some Developments of the Manuscript's Verse":

"Eliot gradually created a more modernist poem, one which resembles a cubist collage: satiric narratives were abandoned in favor of first of dramatic poetry and then of a bold amalgamation of genres. The speakers shifted from omniscient narrators to a variety of separate-person voices and then to different voices of one shadowy character."[citation needed]

The collage combines seemingly disparate parts or "fragments" of different voices, pieces of mythology, popular song, speeches, and other utterances in an attempt to create a somewhat cohesive whole.[citation needed]

The best known Bengali long poem is JAKHAM (The Wound) written by Malay Roy Choudhury of India during the famous Hungryalist movement in 1960s.

A montage is similar to a collage in that it consists of many voices, most famously portrayed in Langston Hughes' Montage of a Dream Deferred. The poet provides a comprehensive portrait of 20th century Harlem through the use of numerous different voices and thus creates a cohesive whole through this fragmentary lens.

What is perhaps the most debatable characteristic of this collage/montage form is the question of what is added to the message or content of the poem by using a more fragmented view. This debate is clearly visible within Langston Hughes' Montage in the question of who the primary voice belongs to and what is added by having Harlem shown through multiple people, as opposed to Hughes simply speaking from his own understanding of what makes Harlem.

Verse-narrative[edit]

A verse narrative, as one might expect, is simply a narrative poem, a poem that tells a story. What is interesting about this subgenre is that owing to its place in the flexible category of long poem, the verse-narrative may have disrupted convention by telling its story in both poem and narrative. This combination broadens the scope of both genres, lending the poem's depth that may be lacking in the other subgenres, yet also a lyrical voice that defines it as poetry. For an example of this, one might turn to Gilgamesh, which encompasses both the subgenres Epic and Verse-Narrative.

As one of the main subgenres, Verse-Narrative gets the least attention because it so effortlessly overlaps the other subgenres. It does not necessarily have the components of an Epic, nor the lyricism and shifting scope of a Lyric Sequence or a Lyric Series, nor the close relation to narrative of Verse Novel. It exists for critics generally as an accepted part of the long poem Tradition.

Romantic long poem[edit]

The critic Lilach Lachman describes the Romantic long poem as one that, "questioned the coherence of the conventional epic's plot, its logic of time and space, and its laws of interconnecting the narrative through action." Examples of the Romantic long poem is Keats' long poem Hyperion: A Fragment (1820), William Wordsworth's Recluse (Including the Prelude (1850), and The Excursion), and Percy Bysshe Shelley's Prometheus Unbound.

The Romance long poem contains many of the same components of the Romance Lyric. Michael O'Neil suggests that "much romantic poetry is torn out of its own despair" and, in fact, can exist as the tremulous fusion between "self-trust and self-doubt."

Meditations[edit]

Meditations are reflective thought poems. Like the Montage and the Series subgenres, Meditations can be somewhat fragmented, yet their connectivity is what makes the long poem a coherent and cohesive idea. This subgenre is based on meditations (or thoughts). Wallace Stevens believes, as do other writers in this genre, that the work does not rely on the use of multiple voices.

In her essay "The Twentieth Century Long Poem," Lynn Keller states that a more philosophical influence on these meditative long poems deals with relating imagination to reality, specifically in long poems by Wallace Stevens. Keller notes, "Uninterested in American landscape, American history, modern mechanical triumphs, or the urban scene, his process-oriented long poems are speculative philosophical works exploring the relation of imagination to reality and the imagination's role in compensating for the loss of religious belief."

W. H. Auden's New Year Letter is an example of a long-form meditative poem.

See also[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Spodek, Howard; Richard Mason (2006). The World's History (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education. p. 224. ISBN 0-13-177318-6. OCLC 60745253. (Two volumes—volume 1: Prehistory to 1500?)

- ^ Keller 1997, p. 1

- ^ a b Keller 1993

- ^ Miller 1979

- ^ Poe 1850

- ^ Weiss 1993

- ^ Keller 1997, p. ???

- ^ Conte 1992, p. ??

General references[edit]

- Conte, Joseph (Spring–Fall 1992), "Seriality and the Contemporary Long Poem", Sagetrieb (11): 35–45.

- Friedman. "When a 'Long' Poem Is a 'Big' Poem: Self Authorizing Strategies in Women's Twentieth-Century 'Long Poems'". LIT 2 (1990): 9-25.

- Friedman, Susan Stanford. {{"'Born of One Mother': Re-Vision of Patriarchal Tradition". Psyche Reborn: The Emergence of H. D. Bloomington: Indiana U. Press, 1981. pp. 253-272.

- Jung, Sandro (Spring 2007), "Epic, Ode, or Something New: The Blending of Genres in Thomson's "Spring"", Papers on Language & Literature, 43 (2): 146–165, retrieved 2008-04-01.

- Keller, Lynn (1997), "Pushing the Limits of Genre and Gender: Women's Long Poems as Forms of Expansion", Forms of Expansion: Recent Long Poems by Women, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Keller, Lynn. "The Twentieth-Century Long Poem", in Jay Parini, ed. The Columbia History of American Poetry. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993: 534-563.

- Lachman, Lilach. "Keats's Hyperion: Time, Space, and the Long Poem" in Poetics Today, Vol. 22, No. 1, Spring, 2001, pp. 89–127.

- Miller, James E., Jr. "The Care and Feeding of Long Poems: The American Epic from Barlow to Berryman". The American Quest for a Supreme Fiction: Whitman's Legacy in the Personal Epic. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1979.

- Murphy, Patrick D. (January 1989), "The Verse Novel: A Modern American Poetic Genre", College English, 51 (1), National Council of Teachers of English: 57–72, doi:10.2307/378185, JSTOR 378185.

- O'Neill, Michael. "'Driven as in surges': texture and voice in Romantic poetry." Wordsworth Circle 38.3, Summer 2007), 5-7.

- Sinnreich-Levi, Deborah M. (ed.). "Oton de Grandson". Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 208: Literature of the French and Occitan Middle Ages: Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Stevens Institute of Technology and Ian S. Laurie, Flinders University. The Gale Group, 1999, pp. 141–148.

- Poe, Edgar Allan, The Poetic Principle.

- Shoptaw, John, "Lyric Incorporated: The Serial Object of George Oppen and Langston Hughes", in Sagetrieb, Vol. 12, No. 3, Winter 1993, pp. 105–24. Reprinted in Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism, Vol. 107. Reproduced in Literature Resource Center.

- Taylor, Olivia Gatti. "Written in Blood: The Art of Mothering Epic in the Poetry of Elizabeth Barrett Browning." Victorian Poetry, 44:2 (2006 Summer), pp. 153–64.

- Vickery, Walter N. "Alexander Pushkin", In Twayne's World Authors Series Online New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1999 Previously published in print in 1992 by Twayne Publishers. Source database: Twayne's World Authors.

- Weiss, Tedd (July–August 1993), "The long poem: sequence or consequence?", The American Poetry Review, 22 (4): 37–48.