Liberty

This article possibly contains original research. (October 2022) |

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views.[1] The concept of liberty can have different meanings depending on context. In Christian theology, liberty is freedom from the effects of "sin, spiritual servitude, [or] worldly ties".[2] In the Constitutional law of the United States, Ordered liberty means creating a balanced society where individuals have the freedom to act without unnecessary interference (negative liberty) and access to opportunities and resources to pursue their goals (positive liberty), all within a fair legal system.

Sometimes liberty is differentiated from freedom by using the word "freedom" primarily, if not exclusively, to mean the ability to do as one wills and what one has the power to do; and using the word "liberty" to mean the absence of arbitrary restraints, taking into account the rights of all involved. In this sense, the exercise of liberty is subject to capability and limited by the rights of others. Thus liberty entails the responsible use of freedom under the rule of law without depriving anyone else of their freedom. Liberty can be taken away as a form of punishment. In many countries, people can be deprived of their liberty if they are convicted of criminal acts.

Liberty originates from the Latin word libertas, derived from the name of the goddess Libertas, who, along with more modern personifications, is often used to portray the concept, and the archaic Roman god Liber.[citation needed] The word "liberty" is often used in slogans, such as in "Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness"[3] and "Liberté, égalité, fraternité".[4]

Philosophy[edit]

Philosophers from the earliest times have considered the question of liberty. Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180 AD) wrote:

a polity in which there is the same law for all, a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed.[5]

According to compatibilist Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679):

a free man is he that in those things which by his strength and wit he is able to do is not hindered to do what he hath the will to do.

— Leviathan, Part 2, Ch. XXI.

John Locke (1632–1704) rejected that definition of liberty. While not specifically mentioning Hobbes, he attacks Sir Robert Filmer who had the same definition. According to Locke:

In the state of nature, liberty consists of being free from any superior power on Earth. People are not under the will or lawmaking authority of others but have only the law of nature for their rule. In political society, liberty consists of being under no other lawmaking power except that established by consent in the commonwealth. People are free from the dominion of any will or legal restraint apart from that enacted by their own constituted lawmaking power according to the trust put in it. Thus, freedom is not as Sir Robert Filmer defines it: 'A liberty for everyone to do what he likes, to live as he pleases, and not to be tied by any laws.' Freedom is constrained by laws in both the state of nature and political society. Freedom of nature is to be under no other restraint but the law of nature. Freedom of people under government is to be under no restraint apart from standing rules to live by that are common to everyone in the society and made by the lawmaking power established in it. Persons have a right or liberty to (1) follow their own will in all things that the law has not prohibited and (2) not be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, and arbitrary wills of others.[6]

John Stuart Mill, in his 1859 work, On Liberty, was the first to recognize the difference between liberty as the freedom to act and liberty as the absence of coercion.[7]

In his 1958 lecture "Two Concepts of Liberty", Isaiah Berlin formally framed the differences between two perspectives as the distinction between two opposite concepts of liberty: positive liberty and negative liberty. The latter designates a negative condition in which an individual is protected from tyranny and the arbitrary exercise of authority, while the former refers to the liberty that comes from self-mastery, the freedom from inner compulsions such as weakness and fear.[8]

Politics[edit]

History[edit]

The modern concept of political liberty has its origins in the Greek concepts of freedom and slavery.[9] To be free, to the Greeks, was not to have a master, to be independent from a master (to live as one likes).[10][11] That was the original Greek concept of freedom. It is closely linked with the concept of democracy, as Aristotle put it:

- "This, then, is one note of liberty which all democrats affirm to be the principle of their state. Another is that a man should live as he likes. This, they say, is the privilege of a freeman, since, on the other hand, not to live as a man likes is the mark of a slave. This is the second characteristic of democracy, whence has arisen the claim of men to be ruled by none, if possible, or, if this is impossible, to rule and be ruled in turns; and so it contributes to the freedom based upon equality."[12]

This applied only to free men. In Athens, for instance, women could not vote or hold office and were legally and socially dependent on a male relative.[13]

The populations of the Persian Empire enjoyed some degree of freedom. Citizens of all religions and ethnic groups were given the same rights and had the same freedom of religion, women had the same rights as men, and slavery was abolished (550 BC). All the palaces of the kings of Persia were built by paid workers in an era when slaves typically did such work.[14]

In the Maurya Empire of ancient India, citizens of all religions and ethnic groups had some rights to freedom, tolerance, and equality. The need for tolerance on an egalitarian basis can be found in the Edicts of Ashoka the Great, which emphasize the importance of tolerance in public policy by the government. The slaughter or capture of prisoners of war also appears to have been condemned by Ashoka.[15] Slavery also appears to have been non-existent in the Maurya Empire.[16] However, according to Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, "Ashoka's orders seem to have been resisted right from the beginning."[17]

Roman law also embraced certain limited forms of liberty, even under the rule of the Roman Emperors. However, these liberties were accorded only to Roman citizens. Many of the liberties enjoyed under Roman law endured through the Middle Ages, but were enjoyed solely by the nobility, rarely by the common man.[citation needed] The idea of inalienable and universal liberties had to wait until the Age of Enlightenment.

Social contract[edit]

The social contract theory, most influentially formulated by Hobbes, John Locke and Rousseau (though first suggested by Plato in The Republic), was among the first to provide a political classification of rights, in particular through the notion of sovereignty and of natural rights. The thinkers of the Enlightenment reasoned that law governed both heavenly and human affairs, and that law gave the king his power, rather than the king's power giving force to law. This conception of law would find its culmination in the ideas of Montesquieu. The conception of law as a relationship between individuals, rather than families, came to the fore, and with it the increasing focus on individual liberty as a fundamental reality, given by "Nature and Nature's God," which, in the ideal state, would be as universal as possible.

In On Liberty, John Stuart Mill sought to define the "...nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual," and as such, he describes an inherent and continuous antagonism between liberty and authority and thus, the prevailing question becomes "how to make the fitting adjustment between individual independence and social control".[18]

Origins of political freedom[edit]

England and Great Britain[edit]

Timeline:

- 1066 – as a condition of his coronation William the Conqueror assented to the London Charter of Liberties which guaranteed the "Saxon" liberties of the City of London.

- 1100 – the Charter of Liberties is passed which sets out certain liberties of nobles, church officials and individuals.

- 1166 – Henry II of England transformed English law by passing the Assize of Clarendon. The act, a forerunner to trial by jury, started the abolition of trial by combat and trial by ordeal.[19]

- 1187-1189 – publication of Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Anglie which contains authoritative definitions of freedom and servitude.

- 1215 – Magna Carta was enacted, becoming the cornerstone of liberty in first England, then Great Britain, and later the world.[20][21]

- 1628 – the English Parliament passed the Petition of Right which set out specific liberties of English citizens.

- 1679 – the English Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act which outlawed unlawful or arbitrary imprisonment.

- 1689 – the Bill of Rights granted "freedom of speech in Parliament", and reinforced many existing civil rights in England. The Scots law equivalent the Claim of Right is also passed.[22]

- 1772 – the Somerset v Stewart judgement found that slavery was unsupported by common law in England and Wales.

- 1859 – an essay by the philosopher John Stuart Mill, entitled On Liberty, argued for toleration and individuality. "If any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility."[23][24]

- 1948 – British representatives attempted to but were prevented from adding a legal framework to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (It was not until 1976 that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights came into force, giving a legal status to most of the Declaration.)[25]

- 1958 – Two Concepts of Liberty, by Isaiah Berlin, identified "negative liberty" as an obstacle, as distinct from "positive liberty" which promotes self-mastery and the concepts of freedom.[26]

United States[edit]

According to the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence, all people have a natural right to "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness". This declaration of liberty was troubled for 90 years by the continued institutionalization of legalized Black slavery, as slave owners argued that their liberty was paramount since it involved property, their slaves, and that Blacks had no rights that any White man was obliged to recognize. The Supreme Court, in the 1857 Dred Scott decision, upheld this principle. In 1866, after the American Civil War, the US Constitution was amended to extend rights to persons of color, and in 1920 voting rights were extended to women.[27]

By the later half of the 20th century, liberty was expanded further to prohibit government interference with personal choices. In the 1965 United States Supreme Court decision Griswold v. Connecticut, Justice William O. Douglas argued that liberties relating to personal relationships, such as marriage, have a unique primacy of place in the hierarchy of freedoms.[28] Jacob M. Appel has summarized this principle:

I am grateful that I have rights in the proverbial public square – but, as a practical matter, my most cherished rights are those that I possess in my bedroom and hospital room and death chamber. Most people are far more concerned that they can control their own bodies than they are about petitioning Congress.[29]

In modern America, various competing ideologies have divergent views about how best to promote liberty. Liberals in the original sense of the word see equality as a necessary component of freedom. Progressives stress freedom from business monopoly as essential. Libertarians disagree, and see economic and individual freedom as best. The Tea Party movement sees "big government" as an enemy of freedom.[30][31] Other major participants in the modern American libertarian movement include the Libertarian Party,[32] the Free State Project,[33][34] and the Mises Institute.[35]

France[edit]

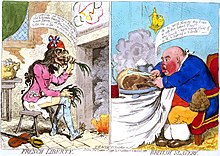

France supported the Americans in their revolt against English rule and, in 1789, overthrew their own monarchy, with the cry of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité". The bloodbath that followed, known as the reign of terror, soured many people on the idea of liberty. Edmund Burke, considered one of the fathers of conservatism, wrote "The French had shewn themselves the ablest architects of ruin that had hitherto existed in the world."[36]

Ideologies[edit]

Liberalism[edit]

According to the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics, liberalism is "the belief that it is the aim of politics to preserve individual rights and to maximize freedom of choice". But they point out that there is considerable discussion about how to achieve those goals. Every discussion of freedom depends on three key components: who is free, what they are free to do, and what forces restrict their freedom.[37] John Gray argues that the core belief of liberalism is toleration. Liberals allow others freedom to do what they want, in exchange for having the same freedom in return. This idea of freedom is personal rather than political.[38] William Safire points out that liberalism is attacked by both the Right and the Left: by the Right for defending such practices as abortion, homosexuality, and atheism, and by the Left for defending free enterprise and the rights of the individual over the collective.[39]

Libertarianism[edit]

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, libertarians hold liberty as their primary political value.[40] Their approach to implementing liberty involves opposing any governmental coercion, aside from that which is necessary to prevent individuals from coercing each other.[41]

Libertarianism is guided by the principle commonly known as the Non-Aggression Principle (NAP). The Non-Aggression Principle asserts that aggression against an individual or an individual's property is always an immoral violation of one's life, liberty, and property rights.[42][43] Utilizing deceit instead of consent to achieve ends is also a violation of the Non-Aggression principle. Therefore, under the framework of the Non-Aggression principle, rape, murder, deception, involuntary taxation, government regulation, and other behaviors that initiate aggression against otherwise peaceful individuals are considered violations of this principle.[44] This principle is most commonly adhered to by libertarians. A common elevator pitch for this principle is, "Good ideas don't require force."[45]

Republican liberty[edit]

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

According to republican theorists of freedom, like the historian Quentin Skinner[46][47] or the philosopher Philip Pettit,[48] one's liberty should not be viewed as the absence of interference in one's actions, but as non-domination. According to this view, which originates in the Roman Digest, to be a liber homo, a free man, means not being subject to another's arbitrary will, that is to say, dominated by another. They also cite Machiavelli who asserted that you must be a member of a free self-governing civil association, a republic, if you are to enjoy individual liberty.[49]

The predominance of this view of liberty among parliamentarians during the English Civil War resulted in the creation of the liberal concept of freedom as non-interference in Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan.[citation needed]

Socialism[edit]

Socialists view freedom as a concrete situation as opposed to a purely abstract ideal. Freedom is a state of being where individuals have agency to pursue their creative interests unhindered by coercive social relationships, specifically those they are forced to engage in as a requisite for survival under a given social system. Freedom thus requires both the material economic conditions that make freedom possible alongside social relationships and institutions conducive to freedom.[50]

The socialist conception of freedom is closely related to the socialist view of creativity and individuality. Influenced by Karl Marx's concept of alienated labor, socialists understand freedom to be the ability for an individual to engage in creative work in the absence of alienation, where "alienated labor" refers to work people are forced to perform and un-alienated work refers to individuals pursuing their own creative interests.[51]

Marxism[edit]

For Karl Marx, meaningful freedom is only attainable in a communist society characterized by superabundance and free access. Such a social arrangement would eliminate the need for alienated labor and enable individuals to pursue their own creative interests, leaving them to develop and maximize their full potentialities. This goes alongside Marx's emphasis on the ability of socialism and communism progressively reducing the average length of the workday to expand the "realm of freedom", or discretionary free time, for each person.[52][53] Marx's notion of communist society and human freedom is thus radically individualistic.[54]

Anarchism[edit]

While many anarchists see freedom slightly differently, all oppose authority, including the authority of the state, of capitalism, and of nationalism.[55] For the Russian revolutionary anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, liberty did not mean an abstract ideal but a concrete reality based on the equal liberty of others. In a positive sense, liberty consists of "the fullest development of all the faculties and powers of every human being, by education, by scientific training, and by material prosperity." Such a conception of liberty is "eminently social, because it can only be realized in society," not in isolation. In a negative sense, liberty is "the revolt of the individual against all divine, collective, and individual authority."[56]

Historical writings on liberty[edit]

- John Locke (1689). Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, the False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. the Latter Is an Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government. London: Awnsham Churchill.

- Frédéric Bastiat (1850). The Law. Paris: Guillaumin & Co.

- John Stuart Mill (1859). On Liberty. London: John W Parker and Son.

- James Fitzjames Stephen (1874). Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. London: Smith, Elder, & Co.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Stevenson, Angus; Lindberg, Christine A., eds. (2010-01-01). "New Oxford American Dictionary". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195392883.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-539288-3. Archived from the original on 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2023-06-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Oxford English Dictionary, liberty Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine: "Freedom from the bondage or dominating influence of sin, spiritual servitude, worldly ties."

- ^ United States Declaration of Independence, The World Almanac, 2016, ISBN 978-1-60057-201-2.

- ^ "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity – France in the United States / Embassy of France in Washington, DC". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ^ Marcus Aurelius, "Meditations", Book I, Wordsworth Classics of World Literature, ISBN 1-85326-486-5

- ^ Two Treatises on Government: A Translation into Modern English, ISR, 2009, p. 76

- ^ Westbrooks, Logan Hart (2008) "Personal Freedom" p. 134 In Owens, William (compiler) (2008) Freedom: Keys to Freedom from Twenty-one National Leaders Main Street Publications, Memphis, Tennessee, pp. 3–38, ISBN 978-0-9801152-0-8

- ^ Metaphilosoph: Motives for Philosophizing Debunking and Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations. Kelly Dean Jolley. pp. 262–270 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007) The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery: A–K; Vol. II, L–Z, [page needed]

- ^ Mogens Herman Hansen, 2010, Democratic Freedom and the Concept of Freedom in Plato and Aristotle

- ^ Baldissone, Riccardo (2018). Farewell to Freedom: A Western Genealogy of Liberty. doi:10.16997/book15. ISBN 978-1911534600. S2CID 158916040.

- ^ Aristotle, Politics 6.2

- ^ Mikalson, Jon (2009). Ancient Greek Religion (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4051-8177-8.

- ^ Arthur Henry Robertson, John Graham Merrills (1996). Human Rights in the World: An Introduction to the Study of the International Protection of Human Rights. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4923-7.[page needed]

- ^ Amartya Sen (1997). Human Rights and Asian Values. ISBN 0-87641-151-0.[page needed]

- ^ Arrian, Indica:

"This also is remarkable in India, that all Indians are free, and no Indian at all is a slave. In this the Indians agree with the Lacedaemonians. Yet the Lacedaemonians have Helots for slaves, who perform the duties of slaves; but the Indians have no slaves at all, much less is any Indian a slave."

- ^ Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A history of India. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 0-415-32920-5

- ^ Mill, J. S. (1869), "Chapter I: Introductory" Archived 2020-08-03 at the Wayback Machine, On Liberty.

- ^ "The History of Human Rights". Liberty. 2010-07-20. Archived from the original on 2015-03-24. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham 2004, p. 278.

- ^ Breay 2010, p. 48.

- ^ "Bill of Rights". British Library. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Mill, John Stuart (1859). On Liberty (2nd ed.). London: John W.Parker & Son. p. 1.

editions:HMraC_Owoi8C.

- ^ Mill, John Stuart (1864). On Liberty (3rd ed.). London: Longman, Green, Longman Roberts & Green.

- ^ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Final authorized text ed.). The British Library. 1952. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Carter, Ian (5 March 2012). "Positive and Negative Liberty". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 14 September 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ The Constitution of the United States of America, The World Almanac and book of facts (2012), pp. 485–486, Amendment XIV "Citizenship Rights not to be abridged.", Amendment XV "Race no bar to voting rights.", Amendment XIX, "Giving nationwide suffrage to women.". World Almanac Books, ISBN 978-1-60057-147-3.

- ^ Griswold v. Connecticut. 381 U.S. 479 (1965) Decided June 7, 1965

- ^ "A Culture of Liberty". The Huffington Post. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics, 3rd edition, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-19-920516-5.

- ^ Capitol Reader (2013). Summary of Give Us Liberty: A Tea Party Manifesto – Dick Armey and Matt Kibbe. Primento. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-2-511-00084-7.

Haidt, Jonathan (16 October 2010). "What the Tea Partiers Really Want". Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

Ronald P. Formisano (2012). The Tea Party: A Brief History. JHU Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4214-0596-4. - ^ "About the Libertarian Party". Archived from the original on May 8, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ "Is the Free State Project a Better Idea than the Libertarian Party?". July 30, 2021. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Free State Project Grows Up". June 2013. Archived from the original on 2022-05-16. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ "What is the Mises Institute". 18 June 2014. Archived from the original on 20 November 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Clark, J.C.D., Edmund Burke: Reflections on the Revolution in France: a Critical Edition, 2001, Stanford. pp. 66–67, ISBN 0-8047-3923-4.

- ^ Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-19-920516-5.[page needed]

- ^ John Gray, Two Faces of Liberalism, The New Press, 1990, ISBN 1-56584-589-7.[page needed]

- ^ William Safire, Safire's Political Dictionary, "Liberalism takes criticism from both the right and the left,...", p. 388, Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-534334-2.

- ^ "Libertarianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2015-05-04. Retrieved 2014-05-20.

libertarianism, political philosophy that takes individual liberty to be the primary political value

- ^ David Kelley, "Life, liberty, and property." Social Philosophy and Policy (1984) 1#2 pp. 108–118.

- ^ "For Libertarians, There Is Only One Fundamental Right". 29 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ ""The Morality of Libertarianism"". 1 October 2015. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "The Non-Aggression Axiom of Libertarianism". Lew Rockwell. Archived from the original on 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ """Good ideas don't require force"". 4 July 2021. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Quentin Skinner, contributor and co-editor, Republicanism: A Shared European Heritage, Volume I: Republicanism and Constitutionalism in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-521-67235-1[page needed]

- ^ Quentil Skinner, contributor and co-editor, Republicanism: A Shared European Heritage, Volume II: The Values of Republicanism in Early Modern Europe Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-521-67234-4[page needed]

- ^ Philip Pettit, Republicanism: a theory of freedom and government, 1997

- ^ The Foundations of Modern Political Thought: Volume 1, The Renaissance, By Quentin Skinner

- ^ Bhargava, Rajeev (2008). Political Theory: An Introduction. Pearson Education India. p. 255.

Genuine freedom as Marx described it, would become possible only when life activity was no longer constrained by the requirements of production or by the limitations of material scarcity...Thus, in the socialist view, freedom is not an abstract ideal but a concrete situation that ensues only when certain conditions of interaction between man and nature (material conditions), and man and other men (social relations) are fulfilled.

- ^ Goodwin, Barbara (2007). Using Political Ideas. Wiley. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-0-470-02552-9.

Socialists consider the pleasures of creation equal, if not superior, to those of acquisition and consumption, hence the importance of work in socialist society. Whereas the capitalist/Calvinist work ethic applauds the moral virtue of hard work, idealistic socialists emphasize the joy. This vision of 'creative man', Homo Faber, has consequences for their view of freedom...Socialist freedom is the freedom to unfold and develop one's potential, especially through unalienated work.

- ^ Wood, John Cunningham (1996). Karl Marx's Economics: Critical Assessments I. Routledge. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-415-08714-8.

Affluence and increased provision of free goods would reduce alienation in the work process and, in combination with (1), the alienation of man's 'species-life'. Greater leisure would create opportunities for creative and artistic activity outside of work.

- ^ Peffer, Rodney G. (2014). Marxism, Morality, and Social Justice. Princeton University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-691-60888-4.

Marx believed the reduction of necessary labor time to be, evaluatively speaking, an absolute necessity. He claims that real wealth is the developed productive force of all individuals. It is no longer the labor time but the disposable time that is the measure of wealth.

- ^ "Karl Marx on Equality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ The Routledge companion to social and political philosophy. Gaus, Gerald F., D'Agostino, Fred. New York: Routledge. 2013. ISBN 978-0415874564. OCLC 707965867.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)[page needed] - ^ "Works of Mikhail Bakunin 1871". www.marxists.org. Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

Bibliography[edit]

- Breay, Claire (2010). Magna Carta: Manuscripts and Myths. London: The British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-5833-0.

- Breay, Claire; Harrison, Julian, eds. (2015). Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy. London: The British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-5764-7.

- Danziger, Danny; Gillingham, John (2004). 1215: The Year of Magna Carta. Hodder Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-340-82475-7.