John Fortescue (judge)

Sir John Fortescue | |

|---|---|

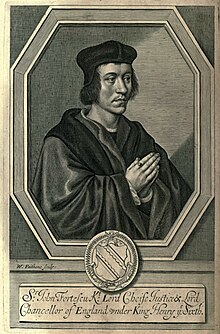

A portrait of Fortescue by William Faithorne published in 1663 inscribed "Sr John Fortescu Kt Lord Cheife Justice & Lord Chancellor of England vnder King Henry ye Sixth" | |

| Chief Justice of the King's Bench | |

| In office 25 January 1442 – Easter term 1460 | |

| Appointed by | Henry VI |

| Preceded by | John Hody |

| Succeeded by | John Markham |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1394 Norris, North Huish, Devon, England |

| Died | 1479 (aged 84–85) |

| Resting place | St. Eadburgha's Church, Ebrington, Gloucestershire, England 52°3′28.98″N 1°44′0.92″W / 52.0580500°N 1.7335889°W |

| Alma mater | Exeter College, Oxford |

Sir John Fortescue (c. 1394 – December 1479), of Ebrington in Gloucestershire, was Chief Justice of the King's Bench and was the author of De Laudibus Legum Angliae (Commendation of the Laws of England),[2] first published posthumously circa 1543, an influential treatise on English law. In the course of Henry VI's reign, Fortescue was appointed one of the governors of Lincoln's Inn three times and served as a Member of Parliament from 1421 to 1437.[3] He became one of the King's Serjeants during the Easter term of 1441, and subsequently served as Chief Justice of the King's Bench from 25 January 1442 to Easter term 1460.[4][5][6]

During the Wars of the Roses, Henry VI was deposed in 1461 by Edward of York, who ascended the throne as Edward IV. Henry and his queen, Margaret of Anjou, later fled to Scotland. Fortescue remained loyal to Henry, and as a result was attainted of treason. He is believed to have been given the nominal title of Chancellor of England during Henry's exile. He accompanied Queen Margaret and her court while they remained on the Continent[2] between 1463 and 1471, and wrote De Laudibus Legum Angliae for the instruction of young Prince Edward. After the defeat of the House of Lancaster, he submitted to Edward IV who reversed his attainder in October 1471.

Origins[edit]

Born about 1397, he was the second son of John Fortescue and his first wife Clarice. His elder brother was Henry Fortescue. The earliest surviving record of the Fortescue family relates to their manor of Whympston in the parish of Modbury, Devon.[7]

Career[edit]

He was educated at Exeter College, Oxford,[2] favoured by many Devonshire gentry families. He was elected as a Member of Parliament for Tavistock (1421 to 1425), Totnes (1426 and 1432), Plympton Erle (1429) and Wiltshire (1437).[3]

During the reign of Henry VI, Fortescue was thrice appointed one of the governors of Lincoln's Inn. During the Easter term of 1441 he was made one of the King's Serjeants, and on 25 January in the following year Chief Justice of the King's Bench, a position he held till Easter term 1460.[8] As a judge Fortescue was recommended for his wisdom, gravity and uprightness, and he is said to have been favoured by the king.[2]

He held his office during the remainder of the reign of Henry VI, to whom he was loyal; as a result, he was attainted of treason in the first parliament of Edward IV. When Henry subsequently fled to Scotland, he is supposed to have appointed Fortescue, who appears to have accompanied him in his flight, Chancellor of England.[2] Fortescue referred to himself in this manner on the title page of De Laudibus Legum Angliae, but as the King did not possess the Great Seal of England during his exile it has been suggested that the title was "nominal" and "merely illusory".[9]

In 1463 Fortescue accompanied Queen Margaret and her court in their exile on the Continent, and returned with them to England in 1471. During their exile he wrote for the instruction of the young Prince Edward his celebrated work De laudibus legum Angliæ[2] (Commendation of the Laws of England, first published posthumously around 1543),[10] in which he made the first expression of what would later become known as Blackstone's formulation, stating that "one would much rather that twenty guilty persons should escape the punishment of death, than that one innocent person should be condemned, and suffer capitally". On the defeat of the Lancastrian party he made his submission to Edward IV, who reversed his attainder on 13 October 1471.[2][11]

Family[edit]

By 1423 he was married to Elizabeth Bright, daughter of Robert Bright from Doddiscombsleigh in Devon, but in 1426 she died without coming into her inheritance and without children. By 1436 he was married to Isabella James, daughter and heiress of John James who held land at Norton St Philip in Somerset as well as in Wiltshire, and they had three known children:[5][4][6]

- Martin Fortescue, born about 1430 and died 1472, who in 1454 married Elizabeth Denzill, daughter and heiress of Richard Denzill, landholder at Filleigh, Weare Giffard, Buckland Filleigh and other places in Devon. [6]

- Elizabeth Fortescue, who in 1455 married Edward Whalesborough.[6]

- Maud Fortescue, who in 1456 married Robert Corbet.[6]

Death and burial[edit]

The exact date of Fortescue's death is not known, but is believed to be shortly before 18 December 1479.[3] He was buried in the Church of St Eadburga, Ebrington in Gloucestershire, in the manor he had purchased, and after which his descendants took the name of their title Viscount Ebrington, today used as the courtesy title of the eldest son and heir of Earl Fortescue.[13] A painted stone effigy of John Fortescue, wearing his scarlet robes of office with collar of ermine, exists within the church, against the north wall of the chancel within the communion rails.[14] Above it was erected in 1677 by Col. Robert Fortescue (1617–1677) (eight times his descendant and the second son of Hugh Fortescue (1593–1663) of Filleigh)[15] a mural monument with a biographical inscription in Latin. A smaller tablet is affixed below stating that the monument was repaired in 1765 by Matthew Fortescue, 2nd Baron Fortescue. A brass plate below states: "Restored by the Rt Honble. Hugh, 3rd Earl Fortescue, AD 1861".[16]

Legacy[edit]

John Fortescue's description of England's mixed monarchy as a dominium politicum et regale (a political and regal kingdom) has been profoundly influential in the history of British constitutional thought. During the 20th century, the earlier portrayal of Fortescue as a constitutionalist has come under pressure from legal and constitutional historians.[17] Scholars of literature have taken an interest in Fortescue's contribution to the development of English prose,[18] and in his role as a Lancastrian writer.[19] More recently, Fortescue's constitutional thought has been reassessed and his Lancastrian affiliation has been challenged.[20]

To this day the John Fortescue Society is joined by students of law at Exeter College, Oxford.[21]

Works[edit]

Fortescue's most significant works were composed in Scotland and France, where the Lancastrian party had taken refuge, between 1463 and 1471. Taken together, Opusculum de natura legis naturæ et de ejus censura in successione regnorum suprema (A Small Work on the Nature of the Law of Nature, and on its Judgment on the Succession to Supreme Office in Kingdoms, c. 1463),[23] De laudibus legum Angliæ (1468–1471), and a work written in English around 1471 which was later published as The Difference between an Absolute and Limited Monarchy (1714)[2] and as The Governance of England (1885), provide the first discussion of the political and conceptual underpinnings of the common law, besides commenting on England's constitutional framework.[24] His works, in particular the masterly vindication of the laws of England De laudibus legum Angliæ, circulated in manuscript in late medieval England and were cited by the leading thinkers of the early Tudor period, among them the printer and playwright John Rastell and the lawyer Christopher St. Germain.[20] De laudibus legum Angliae did not appear in print until about 1543 in the reign of Henry VIII as Prenobilis militis, cognomento Forescu [sic], qui temporibus Henrici sexti floruit, de politica administratione, et legibus ciuilibus florentissimi regni Anglie, commentarius (Commentary on Political Administration and on the Civil Laws of the Most Flourishing Kingdom of England, of the Very Noble Knight, surnamed Forescu [sic], who Flourished during the Reign of Henry VI).[10] It was subsequently reprinted many times under different titles.

The Difference between an Absolute and Limited Monarchy,[25] based on Fortescue's c. 1471 manuscript, was published in 1714 by a descendant, John Fortescue Aland. In the Cotton library there is a manuscript of this work, and its title indicates that it was addressed to Henry VI. However, many passages show plainly that it was written in favour of Edward IV. A revised edition of this work, with a historical and biographical introduction, was published in 1885 by Charles Plummer under the title The Governance of England.[2][26]

Fortescue also wrote a number of mostly topical works that addressed the political conflict during the Wars of the Roses. Among the surviving works are the pamphlets De titulo Edwardi comitis Marchiæ (The Title of Edward, Earl of March), Of the Title of the House of York, Defensio juris domus Lancastriæ (Defence of the Rights of the House of Lancaster), Replication ageinste the Clayme, and Title of the Duke of Yorke for the Crownes of England and France, as well as the treatise Opusculum de natura legis naturæ et de ejus censura in successione regnorum suprema already mentioned. Two further works, Declaration upon Certayn Wrytinges Sent oute of Scotteland and Articles Sent to Warwick have been discussed by recent scholarship.[19][27] All of Fortescue's minor writings appear in The Works of Sir John Fortescue, published in 1869 for private circulation by another descendant, Thomas Fortescue, 1st Baron Clermont.[2][28]

A list of Fortescue's printed works and selected later editions follows:

- Fortescue, John (c. 1543), Prenobilis militis, cognomento Forescu [sic], qui temporibus Henrici sexti floruit, de politica administratione, et legibus ciuilibus florentissimi regni Anglie, commentarius [Commentary on Political Administration and on the Civil Laws of the Most Flourishing Kingdom of England, of the Very Noble Knight, surnamed Forescu [sic], who Flourished during the Reign of Henry VI], London: tipis Edwardi Whitechurche, et veneunt in edibus Henrici Smyth bibliopole [printed by Edward Whitechurche, and are sold in the buildings of Henry Smith the bookseller], OCLC 606486248. Later editions:

- Fortescue, John (1567), A Learned Commendation of the Politique Lawes of Englande: VVherin by moste Pitthy Reasons [and] Euident Demonstrations they are Plainelye Proued Farre to Excell aswell the Ciuile Lawes of the Empiere, as also all other Lawes of the World, with a Large Discourse of the Difference betwene the. ii. Gouernements of Kingdomes: Whereof the one is onely Regall, and the other Consisteth of Regall and Polityque Administration Conioyned. Written in Latine aboue an Hundred Yeares Past, by the Learned and Right Honorable Maister Fortescue Knight, Lorde Chauncellour of England in the Time of Kinge Henrye the. vi. And Newly Translated into Englishe by Robert Mulcaster, Mulcaster, Robert, transl., London: Imprinted ... in Fletestrete within Temple Barre, at the signe of the hand and starre, by Rychard Tottill, OCLC 837169265. (According to the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC), further editions were issued under this title in 1573 and 1599.)

- John Fortescue (1616), De laudibus legum Angliæ writen by Sir Iohn Fortescue L. Ch. Iustice, and after L. Chancellor to K. Henry VI. Hereto are ioind the two Summes of Sir Ralph de Hengham L. Ch. Iustice to K. Edward I. commonly calld Hengham magna, and Hengham parua. Neuer before publisht. Notes both on Fortescue and Hengham are added, London: [Printed by Adam Islip?] for the Companie of Stationers, OCLC 837172477. (According to the ESTC, further editions were issued under this title in 1660, 1672, 1737, 1741 and 1775.)

- Waterhouse, Edward (1663), Fortescutus Illustratus, or a Commentary on that Nervous Treatise De laudibus legum Angliæ, Written by Sir John Fortescue Knight, first Lord Chief Justice, after Lord Chancellour to King Henry the Sixth. Which Treatise, Dedicated to Prince Edward that King's Son and Heir (whom he Attended in his Retirement into France, and to whom he Loyally and Affectionately Imparted himself in the Virtue and Variety of his Excellent Discourse) Hee Purposely Wrote to Consolidate his Princely Minde in the Love and Approbation of the Good Lawes of England, and of the Laudable Customs of this Native Country. The Heroique Design of whose Excellent Judgement and Loyal Addiction to his Prince, is Humbly Endeavoured to be Revived, Admired, and Advanced, London: Printed by Tho. Roycroft for Thomas Dicas [etc.], OCLC 830342279

- Fortescue, John (1825), Amos, Andrew (ed.), De laudibus legum Angliæ: The Translation into English Published A.D. MDCCLXXV: The Original Latin Text, with Notes, Cambridge: Printed by J. Smith, Printer to the University, for Joseph Butterworth & Son [et al.], OCLC 60724441.

- Fortescue, John (1917), Sir John Fortescue's Commendation of the Laws of England: The Translation into English of "De laudibus legum Angliæ", Gregor, Francis, transl., London: Sweet and Maxwell, OCLC 60732964.

- Fortescue, John (1714), Aland, John Fortescue (ed.), The Difference between an Absolute and Limited Monarchy: As It More Particularly Regards the English Constitution. Being a Treatise Written by Sir John Fortescue, Kt. Lord Chief Justice, and Lord High Chancellor of England, under King Henry VI. Faithfully Transcribed from the MS. Copy in the Bodleian Library, and Collated with Three Other MSS. Publish'd with Some Remarks by John Fortescue-Aland, of the Inner-Temple, Esq; F.R.S., London: John Fortescue Aland; printed by W. Bowyer in White-Fryars, for E. Parker at the Bible and Crown in Lombard-Street, and T. Ward in the Inner-Temple-Lane, OCLC 642421515. (According to the ESTC, further editions were issued under this title in 1719 and 1724).

- Later editions:

- Fortescue, John (1885), Plummer, Charles (ed.), The Governance of England, otherwise Called the Difference between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 457292673. Digital versions of text are available online, including at The University of Michigan's Corpus of Middle English and Prose and Verse.

- Fortescue, Thomas (1869), The Works of Sir John Fortescue, Knight, Chief Justice of England and Lord Chancellor to King Henry the Sixth, London: Printed for private distribution, OCLC 47732533. [Photo reprints of the original Clermont text are now available, including an edition from The British Library, Historical Print Editions (2011): ISBN 978-1241522131]

- Later editions:

- Modern editions of Fortescue's major works:

- Fortescue, Sir John. (1942), De Laudibus Legum Angliae, Edited and translated by S. B. Chrimes, (2nd Edition: 2011). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, c[includes an extensive introduction along with Latin and English texts]

- Fortescue, Sir John. (1997), On the Laws and Governance of England. Edited by Shelly Lockwood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-58996-7. [includes a new English translation of De Laudibus Legum Angliae, The Governance of England in modern English, and selected passages from the Opusculum de natura legis naturæ and lesser works]

Notes[edit]

- ^ P. W. Montague-Smith, ed. (1968), Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage 1968: With Her Majesty's Royal Warrant Holders: Comprises Information Concerning the Peerage, Privy Councillors, Baronets, Knights, and Companions of Orders, Surrey: Kelly's Directories, p. 461, OCLC 8972816

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Fortescue, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 678.

- ^ a b c "FORTESCUE, John (d.1479), of Devon". History of Parliament Online. The History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b E. W. Ives (22 September 2005). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ a b J.S. Roskell; L. Clark; C.Rawcliffe, eds. (1993). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386-1421. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e John Lambrick Vivian, ed. (1895). The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Herald's Visitations of 1531, 1564, & 1620. Exeter: H. S. Eland. p. 353. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Edward Foss (1851), The Judges of England: With Sketches of their Lives, and Miscellaneous Notices Connected with the Courts at Westminster, from the Time of the Conquest, vol. 4, London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, pp. 308–315 at 308–309, OCLC 23361486.

- ^ Foss, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Foss, pp. 310–312.

- ^ a b John Fortescue (c. 1543), Prenobilis militis, cognomento Forescu [sic], qui temporibus Henrici sexti floruit, de politica administratione, et legibus ciuilibus florentissimi regni Anglie, commentarius [Commentary on Political Administration and on the Civil Laws of the Most Flourishing Kingdom of England, of the Very Noble Knight, surnamed Forescu [sic], who Flourished during the Reign of Henry VI], London: tipis Edwardi Whitechurche, et veneunt in edibus Henrici Smyth bibliopole [printed by Edward Whitechurche, and are sold in the buildings of Henry Smith the bookseller], OCLC 606486248.

- ^ Foss, pp. 313–314.

- ^ "See colour photos". Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Anne Mannooch Welch (1901), "Sir John Fortescue, Buried at Ebrington Gloucestershire" (PDF), Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 24: 193–250, archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2013.

- ^ Foss, p. 314; a photograph can be seen at Painted stone effigy of Lord Chief Justice Sir John Fortescue c1478 on Flickr.

- ^ Vivian, p. 355.

- ^ For heraldry on this monument, see F. Were (1902), "Heraldry" (PDF), Transactions of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 25: 187–211 at 200, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2014.

- ^ Charles Howard McIlwain (1932), The Growth of Political Thought in the West: From the Greeks to the End of the Middle Ages, New York, N.Y.: Macmillan, p. 359, OCLC 494805, and S. B. Chrimes (1934), "Sir John Fortescue and His Theory of Dominion", Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 17 (4th series): 117–147, doi:10.2307/3678523, JSTOR 3678523, S2CID 155648025.

- ^ See, for instance, James Simpson (2004), "Reginald Peacock and John Fortescue", in A. S. G. Edwards (ed.), A Companion to Middle English Prose, Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, pp. 271–287, ISBN 978-1-84384-018-3.

- ^ a b Paul Strohm (2005), Politique: Languages of Statecraft between Chaucer and Shakespeare, South Bend, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN 978-0-268-04114-4.

- ^ a b See Sebastian Sobecki (2015), Unwritten Verities: The Making of England's Vernacular Legal Culture, 1463–1549, Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN 978-0-268-04145-8, a study of Fortescue's influence on late medieval and early Tudor thought.

- ^ See, for example, John Fortescue Society Dinner, Exeter College, Oxford, 2013, archived from the original on 18 October 2013.

- ^ John Fortescue; Ralph de Hengham; Robert Mulcaster, transl. (1616), John Selden (ed.), De Laudibus Legum Angliæ Writen by Sir Iohn Fortescue L. Ch. Iustice, and after L. Chancellor to K. Henry VI. Hereto are Ioind the Two Summes of Sir Ralph de Hengham L. Ch. Iustice to K. Edward I. Commonly Calld Hengham Magna, and Hengham Parua. Neuer before Publisht. Notes both on Fortescue and Hengham are Added (1st ed.), London: [Printed by Adam Islip?] for the Companie of Stationers, OCLC 766455476.

- ^ See John Finnis (2011), Natural Law and Natural Rights (2nd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 258, ISBN 978-0-19-959913-4,

The full title of Fortescue's treatise on natural law is significant: De Natura Legis Naturae et de ejus Censura in Successione Regnorum Suprema ('On the nature of the law of nature, and on its judgment on the succession to supreme office in kingdoms').

- ^ Sobecki, p. 71.

- ^ John Fortescue (1714), John Fortescue Aland (ed.), The Difference between an Absolute and Limited Monarchy: As It More Particularly Regards the English Constitution. Being a Treatise Written by Sir John Fortescue, Kt. Lord Chief Justice, and Lord High Chancellor of England, under King Henry VI. Faithfully Transcribed from the MS. Copy in the Bodleian Library, and Collated with Three Other MSS. Publish'd with Some Remarks by John Fortescue-Aland, of the Inner-Temple, Esq; F.R.S., London: John Fortescue Aland; printed by W. Bowyer in White-Fryars, for E. Parker at the Bible and Crown in Lombard-Street, and T. Ward in the Inner-Temple-Lane, OCLC 642421515.

- ^ John Fortescue (1885), Charles Plummer (ed.), The Governance of England, otherwise Called the Difference between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 457292673.

- ^ Sobecki, pp. 78–80 and 90.

- ^ Thomas Fortescue (1869), The Works of Sir John Fortescue, Knight, Chief Justice of England and Lord Chancellor to King Henry the Sixth, London: Printed for private distribution, OCLC 47732533.

References[edit]

- Fortescue, John (1885), "Introduction", in Plummer, Charles (ed.), The Governance of England, otherwise Called the Difference between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 1–105, OCLC 457292673.

- Fortescue, Thomas (1869), "Life of Sir John Fortescue", The Works of Sir John Fortescue, Knight, Chief Justice of England and Lord Chancellor to King Henry the Sixth, vol. 1, London: Printed for private distribution, pp. 1–55, OCLC 47732533.

- Gairdner, James, ed. (1901–1908), The Paston Letters: 1422–1509 A.D. A Reprint of the Edition of 1872–5, which Contained Upwards of Five Hundred Letters, etc., till then Unpublished, to which are Now Added Others in a Supplement after the Introduction, London: Archibald Constable and Co. Ltd., OCLC 351642996.

Further reading[edit]

- Callahan, Edwin T. (1995), "The Apotheosis of Power: Fortescue on the Nature of Kingship". Majestas vol. 3, p. 35-68.

- Cromartie, Alan. (2004), "Common Law, Counsel and Consent in Fortescue's Political Theory", The Fifteenth Century 4: Political culture in late Medieval Britain p. 45-68.

- Doe, Norman. (1990). Fundamental Authority in Late Medieval English Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521384582.

- Gill, Paul E. (1968), Sir John Fortescue: Chief Justice of the King's Bench, Polemicist of the Succession Problem, Governmental Reformer, and Political Theorist [unpublished Ph.D. thesis], State College, Penn.: Pennsylvania State University, OCLC 13557234.

- Gill, Paul E. (1971), "Politics and Propaganda in Fifteenth-century England: The Polemical Writings of Sir John Fortescue", Speculum, XLVI (2): 333–347, doi:10.2307/2854859, JSTOR 2854859, S2CID 154211521 – discusses Fortescue's role in the succession crisis between the Houses of Lancaster and York.

- Gross, Anthony J. (1996), The dissolution of the Lancastrian kingship: Sir John Fortescue and the crisis of monarchy in fifteenth century England. London: Stamford, ISBN 9781871615906. [foreword by J. R. Lander].

- Jacob, Ernest Frazer. (1953), "Sir John Fortescue and the Law of Nature", Jaccob, Essays in the Conciliar Epoch. Manchester University Press, p. 106-120, 247-248.

- Kekewich, Margaret Lucille. (1998), "Thou shalt be under the power of man". Sir John Fortescue and the Yorkist Succession", Nottingham Medieval Studies vol. 42 (1998) p. 188-230.

- Kelly, M. R. L. L. (2014), "Sir John Fortescue and the Political Dominium: The People, the Common Weal, and the King", Galligan, Denis Ed., Constitutions and the Classics: Patterns of Constitutional Thought from Fortescue to Bentham, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Litzen, Veikko. (1971). "A war of roses and lilies. The theme of succession in Sir John Fortescue's works", Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae B vol. 173 (1971) p. 5-73.

- McGerr, Rosemarie, (2011), A Lancastrian Mirror for Princes: The Yale Law School New Statutes of England. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0253356413.

- Mosse, George L. (1952), "Sir John Fortescue and the Problem of Papal Power", Medievalia et humanistica vol. 7 (1952) p. 89ff.

- Sobecki, Sebastian (2015), Unwritten Verities: The Making of England's Vernacular Legal Culture, 1463–1549, Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN 9780268041458.

- Taylor, Craig David. (1999), "Sir John Fortescue and the French Polemical Treatises of the Hundred Years War", The English Historical Review vol. 114 (1999) p. 112-129.

- John L Watts, (1999) Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65393-0.

- 1394 births

- 1479 deaths

- 15th-century English writers

- English Roman Catholics

- Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

- Serjeants-at-law (England)

- English legal writers

- Fortescue family

- English MPs December 1421

- Knights Bachelor

- Lawyers from Devon

- Lord chief justices of England and Wales

- Burials in Gloucestershire

- English male non-fiction writers

- 15th-century English lawyers

- English MPs 1423

- English MPs 1425

- English MPs 1426

- English MPs 1429

- English MPs 1432

- English MPs 1437

- Members of the Parliament of England for Tavistock