Iceberg that sank the Titanic

The passenger steamer Titanic collided with an iceberg and sank on the night of 14–15 April 1912 in the North Atlantic. Of the approximate 2,200 people on board, over 1,500 did not survive. After the disaster, there was interest in the iceberg itself to explain the circumstances of the collision and the resulting damage to the supposedly unsinkable ship. Because of the Titanic disaster, an International Ice Patrol was founded whose mission was to reduce the dangers of ice to shipping.

The iceberg played a role in the cultural reception of the disaster. As the counterpart to the luxurious ship, it stands for the cold and silent force of nature that cost the lives of so many people. The iceberg became a metaphor in various political and religious contexts. It appears in poetry as well as in pop culture.

The most important sources for the iceberg are reports from surviving crew of the Titanic and passengers of the Titanic. There is also historical data on the weather and currents in the North Atlantic that may help to shed light on the disaster. Ships took photographs of icebergs near the spot where Titanic's lifeboats were found. The iceberg is purportedly visible in one of these photographs.

Origin and fate[edit]

It can only be speculated where and when the Titanic iceberg calved from its glacier. Olson, Doescher, and Sinnott suspect the origin of the fatal iceberg in the Jakobshavn Glacier near Disko Bay on Greenland's west coast. It may have formed in 1910 or 1911 and could have drifted north with the West Greenland Current into Baffin Bay, from where it would have drifted south again thanks to the Labrador Current. An iceberg can, for example, be washed up on the coast or run aground. There it melts, or it comes free again and continues its journey south.[1]

The authors also address the question of whether a certain constellation of the Sun, Earth, and Moon may have had an influence. On 4 January 1912, there was a spring tide at the same time that the Moon was closer to the Earth than usual. This could have influenced the calving of icebergs. However, such an iceberg would hardly have reached the site of the Titanic disaster in April of the same year. But the spring tide may have played a role in refloating a stranded iceberg.[1]

Bigg and Wilton doubt that the solar arrangement of the Moon, Earth, and Sun in question was significant. A few days around 4 January would not have had much influence on calving; in winter, moreover, many fjords were blocked by sea ice. There was also increased iceberg formation in other years. When it comes to calving, they tend to think of factors like the water surface temperature of the Labrador Sea.[2]

For their part, Bigg and Wilton have tried to show a possible path of the fatal iceberg with the help of computer simulations. To do this, they assumed that icebergs at that time originated mainly in the south or southwest of Greenland, whereas today they originate more from the northwest of the island. In 1912, more icebergs were sighted than on average in the 20th century, but it was not an extreme iceberg year.

The warm and wet year 1908 created the conditions for a huge iceberg to travel in the early autumn of 1911 near southwest Greenland. This would have traveled west towards Canada and been transported south by the Labrador Current – along the Canadian coast including Newfoundland, the so-called Iceberg Alley. Because of the systematic observations of icebergs at the time (even before the Ice Patrol was established), it is even very likely, according to Bigg and Wilton, that the later fatal iceberg was sighted in the process.[3]

From 10 to 15 April, there was a high-pressure area over most of the North Atlantic. It remained there for the first three days of the Titanic voyage, ensuring calm seas and clear skies. On 13 April, a depression over Greenland with cold polar air and winds from the northwest drove icebergs south into the shipping lanes. Because of the calm sea, the icebergs hardly created any breakwaters, making them difficult to see at night.[4]

On its way into the Atlantic and also after the collision, the iceberg melted because of the water temperature. An iceberg exists for about two to three years. Accordingly, if the fatal iceberg calved in 1910 or 1911, it may not have disappeared until the end of 1912 or even during 1913.[5] However, considering that the iceberg may have been three years old at the time of the collision, it probably existed for only a week or two after the April 1912 accident, because it may soon have reached the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream.[6]

Ice warnings in April 1912[edit]

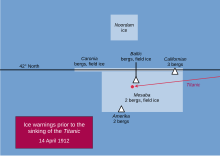

Captain Edward Smith and his officers knew before they left Southampton that the drift ice field was larger in extent and more southerly than in previous years. In addition, several radio reports ("marconigrams") were received from other ships during the voyage, warning the Titanic of drifting ice fields and icebergs.

The first report came on 12 April at 17:46 from the French ship La Touraine, stating that it had sighted thick field ice itself, and that there were ice warnings from the Paris as well, which had seen field ice and two icebergs. On 13 April, Titanic encountered the Furness-Withy steamer Rappahannock, which was heading east. Whether the steamer actually reported an ice field to the Titanic by Morse lamp (as some authors claim) is disputed. It was later reported in a newspaper that the Rappahannock had been damaged in an ice field, but the chief officer of the Rappahannock did not mention that he had reported this to the Titanic.[7]

On the day of the disaster, 14 April, the first information about ice came from the Caronia. First, at 09:12 (Titanic's board time), the Caronia radioed the Titanic that westbound steamers had reported icebergs, growlers (smaller pieces of ice), and field ice along the 42nd parallel. Smith from the Titanic had the marconigram sent to him answered with thanks.[8]

Secondly, the Dutch ship Noordam radioed a message to the Titanic via the Caronia at 11:47. The Noordam informed about an area north of the 42nd parallel: "much ice reported". Smith also thanked her for this message less than an hour later, via the Caronia. Captain Smith showed this marconigram to Second Officer Charles Lightoller, and he had it hung up in the chart room (where it remained the only one).[8]

Later, at 13:49, there was a report from the German steamer Amerika. It had passed two large icebergs. This message was sent to the Hydrographic Office in Washington. With its weak radio equipment, the Amerika itself could not reach the radio station at Cape Race, Newfoundland. However, Titanic's radio cabin received the message and forwarded it to Cape Race (at 21:32). From there, Cape Race telegraphed it on. There is no evidence that the Titanic's bridge received this information.[9]

At around 13:54, the Titanic received a marconigram from the Baltic. It was addressed to Captain Smith and reported:

- The Baltic itself has had fine weather with moderate, variable winds since departure.

- The Greek steamer Athinai had sighted icebergs and extensive drift ice fields during the day. (At a given position on the route of the Titanic.)

- The German oil tanker Deutschland is unable to manoeuvre due to a lack of coal.

Smith had the Baltic thanked at 14:57. Survivor J. Bruce Ismay later testified that Smith gave him this marconigram without comment. It was not until five hours later that Ismay returned the note to Smith at Smith's request.[10]

It remains uncertain whether other officers saw the marconigram. Ismay was the director of the White Star Line, which owned the Titanic. The incident with the Baltic marconigram fueled suspicions that Ismay had exerted undue influence on the captain to keep the Titanic from slowing down despite ice warnings. Thus, in the enquiries after the disaster, people wondered why Captain Smith showed Ismay the marconigram in the first place, or why Ismay claimed that he and Smith did not say a word when the marconigram was handed to them. Ismay portrayed himself as a simple passenger who had only travelled on the Titanic out of curiosity.[11]

In the evening, around 18:30, the Californian observed three large icebergs five miles south of her. She reported this, giving her own position. The Titanic did not learn of this at first, as the device was switched off. It was not until 19:37 that the Titanic received this message, which was addressed to the Antillian.[12] Bride confirmed the message and passed it on to the bridge.

At 21:40 a message came from the Mesaba. It defined an area between points 42° 0′ N, 49° 0′ W and 41° 15′ N, 50° 18′ W. In this imaginary rectangular area it saw: 'much heavy pack ice and great number large icebergs, also field ice.' There is confirmation that the Titanic received the message, but no indication that the message reached Captain Smith.[12]

Radio operator Jack Phillips on the Titanic was very busy: He had a window of only two hours in which to reach Cape Race. Phillips wanted to quickly transmit private messages from passengers. Because other ice warnings had already been received, the message from the Mesaba may no longer have seemed so important to him as to be absolutely necessary to pass on to the bridge.

Cyril Evans, the Californian's radio operator, was the last to radio a message to the Titanic at 22:55. As requested by Captain Stanley Lord, Evans wanted to inform the Titanic that the Californian was surrounded by ice. She had stopped. However, the message lacked the abbreviation MSG, and Evans addressed his colleague informally as old man. Phillips interrupted the contact in the straight diction of radio operators: 'Keep out; shut up, I'm working Cape Race.' ('Keep out of it; shut up, I'm working Cape Race.') He continued to relay messages to Cape Race. Evans on the Californian kept listening for a while and then went to bed.

In summary, the Titanic knew no system for collecting and evaluating ice warnings or other messages related to navigation. The radio operators were not familiar with navigation and could not assess the significance of a message in terms of content. What was important for them was whether a message was clearly addressed to the captain, and then one of the radio operators sought out the captain. Otherwise, they might send a messenger to the bridge. There was probably no procedure for relaying messages, like the one from the Amerika to the Hydrographic Office.[13]

No one in the ship's command saw all the ice warnings. Of the surviving officers, none later remembered the warnings of the Noordam, the Amerika, Baltic, the California or the Mesaba. Captain Smith, for example, only knew the messages from the Caronia, the Noordam and the Baltic. That's why the men believed the ice was north of their own route. None imagined an iceberg that could cross their path.[13]

Iceberg visibility[edit]

On the night of the disaster, Captain Smith assumed that an iceberg would be discovered in time so that it could still be avoided. The decisive factor for him was that the night in question was clear and cloudless. It was generally believed at the time that on clear, albeit dark, nights one could see an iceberg within one to three nautical miles.[a] According to surviving Second Officer Charles Lightoller, he and Smith believed an iceberg was visible at three to four nautical miles. Smith had said that at the slightest sign of haze, the ship should proceed very slowly. The lookouts were instructed to pay particular attention to ice.[14]

In 1925, Fred Zeusler of the United States Coast Guard was in charge of the International Ice Patrol. According to his research, a medium-sized iceberg could be seen a nautical mile away on a moonless, dark but clear night. On the night of the Titanic disaster in 1912, Halpern says, the sea was calm and smooth. Therefore, an iceberg could not be seen from the break of the waves. The only light that could have come from an iceberg would have been reflected starlight. Visibility would have been even worse in the low-hanging haze purported to be extant on the night of the ship's sinking, but survivors' testimonies contradict each other as to whether there was any; other ships reported no haze whatsoever. Possible explanations could be that the witnesses understood different things by 'haze', or that instead of haze, the ice field was actually seen, towards which the Titanic was heading and because of which the Californian had already stopped.[15]

Sighting and collision[edit]

On Sunday 14 April at 23:40 board time, the Titanic collided with an iceberg. Surviving crew members and passengers have testified to this many times. Some survivors saw the iceberg with their own eyes, others perceived a dark shadow. There are also statements about pieces of ice that fell from the iceberg onto the ship. Furthermore, there are statements about how contact with the iceberg was heard or felt.

After the two men in the Titanic's crow's nest sighted the iceberg, one of them, Frederick Fleet, sounded the bell three times to signal that he had seen an object straight ahead of the ship. However, the iceberg may have been seen on the bridge promptly or even simultaneously. According to Fleet's colleague Reginald Lee, the iceberg was only half a nautical mile away (about 900 metres) when it was sighted. According to the British enquiry after the accident, the iceberg was 1500 feet away (about a quarter of a nautical mile or 457 metres) at the time of the sighting. For a ship moving at 22.5 knots (41.7 kilometres per hour), the iceberg would accordingly have been sighted 40 seconds before impact.[16]

The Titanic was still able to steer slightly to port (left) before the impact. Nevertheless, she scraped against the iceberg, which lasted several seconds. As it turned out later, the iceberg caused several leaks on the forward starboard side in the process. Because of the Titanic's high speed, which could not be stopped so quickly, part of the iceberg pressed against the hull below the waterline. This pressure caused rivets to come loose and the outer skin to develop narrow, elongated leaks. Two hours and forty minutes after the impact, the ship sank.

Writer Walter Lord questions whether the iceberg itself may not have been damaged. During the impact under water on the forward side of the ship, ice could have already been scraped off the iceberg to such an extent that the iceberg no longer caused any leaks on the aft starboard side.[13] Fitch, Layton and Wormstedt, on the other hand, follow the thesis that the ship was not damaged aft for a different reason. Initially, the helmsman was indeed ordered to turn to the left, but shortly afterwards he was told to let the ship turn to the right. This manoeuvre, ordered by the First Officer William M. Murdoch, probably prevented the Titanic from shearing off with its stern and touching the iceberg again.[17]

Witness statements on the iceberg itself[edit]

The accident happened twenty minutes before midnight, when hardly anyone was on the decks, owing to why relatively few people saw the iceberg with their own eyes. Witnesses included, above all, the lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee, who both survived.

Lee was the first of the two to be interviewed in the British enquiry. According to him, the iceberg was a dark mass coming through a haze. As the iceberg passed, he saw a white fringe at the top, and only there. Viewed from astern, one side appeared to be white and the other black. It was higher than the foredeck (which was 55 feet (17 m) above the waterline). The attorney-general suspected that by this time the ship had shed some light on the iceberg; Lee concurred.[18]

Fleet could not remember who saw the iceberg first. He saw a black object high above the water, slightly higher than the foredeck. Unlike Lee, Fleet did not remember any haze.[19]

Other surviving crew members had their own accounts of the iceberg:

- Quartermaster Alfred Olliver came onto the open bridge from port and saw the tip of the iceberg rushing past the ship.[20] According to Olliver, the iceberg was about as high as the boat deck or a little higher. He only saw the tip of the iceberg, so he could not estimate its width. Unexpectedly, the iceberg was not white, but a kind of dark blue.[21]

- Quartermaster George Rowe stood under the docking bridge at the stern and hurried towards starboard after feeling the vibration. He saw the tall iceberg slide by less than 10 feet (3.0 m) from the ship. He feared the berg would strike the edge of the docking bridge. The iceberg was about 100 ft (30 m) high.[22][23]

Soon after the collision, Captain Smith and several officers had rushed to the bridge. Smith, Murdoch and Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall went to the starboard side of the bridge to look for the berg. Boxhall (the only survivor among them) was unsure if he still recognised the shape of the berg because his eyes were still adjusting to the darkness.[24]

Passengers either noticed the iceberg as a dark shadow or a white mass that passed by the ship, or sighted the iceberg later from the deck:

- Edith Rosenbaum looked out from her first-class cabin, shortly after the shaking, onto the enclosed promenade deck. She saw a "ghostly wall of white" pass by. George Rheims and Frederick and Jane Hoyt observed something similar.[22] Rosenbaum then went on deck, where there were only five passengers, including William T. Stead. They saw the pieces of ice on the deck and learned from Francis Millet: "Iceberg. [...] We all turned with renewed interest to the great floating mountain of white. It had drifted some distance to starboard and rose indistinctly and mysteriously in the velvet darkness."[25]

- Emma Bucknell and her maid Albina Bazzani saw the iceberg pass by the window in their cabin on D deck. Because of this and the ice on corridors, she dismissed the rumour heard on board that the iceberg was under water. Another woman had said it was higher than D deck, which seemed plausible to Bucknell.[26]

- Eleanor Cassebeer was alarmed by the commotion and went to promenade deck A. With Harry Anderson she went towards the bow. Probably from the railing of the promenade deck they saw small pieces of ice lying. From here they saw the berg rising about 75 to 100 feet (23 to 30 m) out of the sea. They met the ship's designer Thomas Andrews there, whose cabin was nearby. It can be surmised that if they saw the iceberg, Andrews likely did as well.[27]

- Albert and Vera Dick had been woken by the shock and went out onto a deck. Vera remembered seeing the iceberg.[27]

- William Sloper and stewards had rushed onto the deck and were still able to get a quick look at the iceberg.[28]

Witness statements on the collision and the ice on the ship[edit]

A number of passengers later described the experience of the collision as a 'slight shock' or 'jar'. The sound was described by Carrie Chaffee, for example, as if someone was pulling a chain against the side of the ship. Charlotte Collyer experienced the collision as "a long backward jerk, followed by a shorter forward one". Others were not awakened by the impact, or only by the engines stopping soon afterwards, like 12-year-old Ruth Becker. Some went back to sleep; others were extremely concerned.[29]

Parts of the iceberg also hit the Titanic's superstructure on the starboard side. As it passed the forward corrugated deck, large pieces of ice broke off and fell onto the deck of the ship.[20] However, ice from the iceberg could not only be found on the deck:

- First class passenger Edwin Kimball reported ice entering his cabin through the porthole.[22]

- Margaret Swift and Alice Leader were visited by a man holding ice in his hands. He said it was all over the corridor under the portholes.[30]

- In the corridor, Emma Bucknell saw that ice had fallen through a broken porthole onto the floor.[31] She dressed warmly. Back in the corridor she saw two young women talking, one of whom could not believe that the ship had been hit by an iceberg. Bucknell went to the end of the corridor, took pieces of ice and showed them to the women as proof.[30]

- Edith Rosenbaum saw it on the deck: "Someone suggested a snow fight, but it was too cold for that."[27]

- Salon steward Alexander Littlejohn saw 2 feet (0.61 m) of ice in the scuppers (drains for rain or sea water) on the starboard side of the forward well deck.[31]

- Gladys Cherry and her cousin, the Noël Leslie, Countess of Rothes, Alfred Nourney and the Third Officer Pitman saw ice on the well deck.[32]

- Young Jack Thayer and his parents did not see an iceberg, though his father thought he saw pieces of ice floating in the sea.[33]

Bigg and Wilton describe the Titanic iceberg, based on witness testimony, as 50 to 100 feet (15 to 30 m) high and 400 feet (120 m) long. They assume that only 16.7 per cent of a weathered iceberg is above the water surface. Consequently, the fatal iceberg would have been at least 90 to 185 metres (295 to 607 ft) deep and approximately 125 metres (410 ft) long.[34]

Icebergs usually melt on the sides. When the centre of gravity is finally too high, an iceberg tips over. If the fatal iceberg was indeed about 125 m (410 ft) long, the total height would have been up to 100 m (330 ft). Above the water surface, it would therefore have been 15 to 17 m (49 to 56 ft) high, which would fit the witness statements about the height (above the water surface). The mass would have been 2 megatons.[34] According to witnesses, the iceberg had one or two conspicuous peaks, which rules out a table berg.[35]

For size comparison, the Titanic, the largest ship in the world at the time, had a total length of 882 feet and 9 inches (around 269 metres). She was up to 92 feet and 6 inches wide (about 28 metres). Her draught (from waterline to keel) was 34 feet and 6 inches (about 10 metres) in front.[36] The mastheads, when the ship was fully loaded, were about 205 feet (62.5 metres) above the water.[37]

Photographs of the iceberg[edit]

Various ships were in the vicinity of the accident, or at the site where the lifeboats were found. Crew members or passengers on such ships took photographs of icebergs. Some of them were said to have been the iceberg that sank the Titanic. The crew of the SS Birma also photographed what they believed to be the iceberg that sank the Titanic.

Attempts have been made to match the shape of the icebergs in question with the descriptions, and in some cases a line of red paint (from the hull of the ship) was said to have been seen. It should be borne in mind, however, that the drift was continuously driving the icebergs southwards. Moreover, in that April 1912, nearly 400 icebergs crossed the 48th parallel to the south (at Newfoundland, where they have been counted). A certain proportion of these reached the area of the Titanic disaster.[38]

The photographs may nevertheless be of lasting interest. In October 2015, for example, CNN reported on an auction at which one of the iceberg photographs was to be sold. It was a photograph taken aboard the steamer Prinz Adalbert on the morning of 15 April. A note about it from the photographer, a steward on the ship, reported red paint visible on the iceberg. The photo had hung for decades on the walls of a law firm that provided legal representation to the White Star Line. She had bought it shortly after the accident from another client, Hamburg-Amerika-Linie. This client had heard that the law firm would represent the owners of the Titanic with regard to liability. When the firm closed in 2002, the four partners put the photo with the note of red paint up for auction. The auction house Henry Aldridge & Son in Devizes (England) estimated it at 10,000 to 15,000 pounds.[39]

In that CNN report, ice researcher Steve Bruneau explains that the ice of the iceberg behaved like rock during the collision. It is quite possible, he says, that paint was scraped off the ship and pressed into the ice. As long as it did not get underwater and as long as it stayed cool, the paint could have been visible on the iceberg for a day or more.[39]

In 2020, the same auction house announced another auction. This iceberg photo came from Captain Wood of the SS Etonian and was taken as early as 16:00 on 12 April. Wood gave a position at the time (41° 30′ 0″ N, 49° 30′ 0″ W), and it had turned out to be almost exactly where the Titanic hit her iceberg 40 hours later. In a 1913 letter, Wood described the photograph. Henry Aldridge & Son estimated its value at £12,000.[40] (However, the position mentioned is 47 kilometres south-east of the wreck).

Another photo of an iceberg mentioned in the literature was taken by Hope Chapin. She was on her honeymoon aboard the Carpathia and took the photo at daybreak.[41] Bigg and Wilton see the estimated size proportions of the iceberg reflected in the one photographed by Captain de Carteret. He was in command of the Minia, which was searching for bodies at the (supposed) disaster site. According to Bigg and Wilton, the photo shows a red streak of colour.[34]

Cultural reception[edit]

A story has developed around the historic disaster of the passenger liner Titanic with which certain elements are inextricably linked, say Brown, McDonagh and Shultz. These include not only the magnitude of the disaster and the haughty claim of the ship's unsinkability, but also the "nemesis of Mother Nature's iceberg".[42]

There are numerous non-fiction books and novels about the Titanic. But it takes two to make a collision, says Philip Morrison in a review of a book by marine biologist Richard Brown. In Voyage of the Iceberg, Brown describes the disaster from the perspective of the iceberg and, moreover, the possible journey of the iceberg along nature and people in the far north.[43]

A counterpart in poetry is the poem "The Iceberg" by the Canadian Charles G. D. Roberts. In the first-person perspective, the iceberg, an 'alp afloat,' narrates its life journey from its formation on the glacier to its dissolution in the ocean. In the collision, the broadside of the Titanic creeps under the iceberg, which pierces and tears open the hull with a submerged horn. The funnels crash against the rocky slope and the huge mass of the iceberg sinks down onto the ship, wiping it out.

Metaphorical use[edit]

Not only the Titanic, which stands for luxury, but also the iceberg has inspired numerous authors and visual artists. It was common to depict the iceberg as a monster in caricatures.[44] Religious authors denounced a lack of respect for God and the forces of nature, which included the iceberg. The ice warnings that had been ignored by the Titanic appeared as " the writing on the wall". Meanwhile, in leftist publications, the iceberg was sometimes compared to the proletariat: It was causing capitalism (the Titanic) to sink.[45] And if James Cameron's Titanic film had flopped, critics would have said that the iceberg of audience rejection had sunk it.[46]

As a product of a Belfast shipyard, the Titanic could also be seen as a symbol of Protestant pride – which was in danger of being sunk by the cool "iceberg dynamics" of Irish nationalism. The building and sinking of the Titanic took place at the same time as the debates on Irish Home Rule.[47] In the radio play The Iceberg (1975), Stewart Parker, a Northern Irish playwright, allows the ghosts of two shipyard workers who perished during the construction of the Titanic to speak about the Northern Ireland conflict.[48]

Author Stephen Kern sees an analogy between the Titanic disaster and the Sarajevo assassination that helped trigger the First World War: The icebergs on the steamer's route would stand in an analogy to the eight assassins who waited for Franz Ferdinand's carriage.[49] In 2012, for example, Shetsova compared Russia under Putin to the Titanic in search of its iceberg.[50]

New metaphors or perspectives place the fatal iceberg, for example, within the context of climate change. The sea ice is receding and the melting of the Greenland glaciers will initially create more icebergs. However, due to global warming, the probability of large icebergs reaching the 45th parallel and endangering shipping there is decreasing.[35] Sometimes icebergs are no longer seen as a threat, but as the freshwater source of the future.[51]

Thomas Hardy[edit]

As early as 1912, the British poet Thomas Hardy poetically processed the relationship between the ship and the iceberg,[52] in a highly unusual way that defies all expectations.[53] In the much-cited poem The Convergence of the Twain, there is neither suffering nor death; instead, a blind, senseless will is at work, which, in the sense of Schopenhauer, has replaced the personal God of the Bible as a deity.[54]

In The Convergence of the Twain, Hardy first imagines the luxurious ship on the ocean floor. While people were building the Titanic, the iceberg was growing in nature. Then, on the night of the disaster, fate brought ship and iceberg together.

In scholarly literature, explains Emerson Brown Jr., it has become a commonplace that Hardy's language used indicates human sexuality. Nor does speaking about two shaken hemispheres uniting simply refer to the two hemispheres of the world. Rather, it goes back to the Greek comedy writer Aristophanes: the gods divided the originally spherical human being into two parts as punishment, and hence comes his urge to unite in the sexual act.[55]

Furthermore, the poem alludes to marriage as it is discussed in the Gospel of Matthew between the Pharisees and Jesus. Man and woman, for example, appear in it as no longer twain, but one flesh, and the creature of cleaving wing (in the King James translation) also refers to this. There are other erotic and Christian references in Hardy's poem.[56]

Thus Hardy sends the 1500 souls into the depths with an 'obscene pun', as Meredith Bergmann puts it. Consummation comes describes the sexual union of the ship, conceived as female, with the iceberg. But this line 33 also reflects the last words of the 33-year-old Jesus Christ: consummatum est (It is finished).[54]

Emerson Brown Jr. says that the poem shows no compassion for the people who perished in the disaster. The dead children of the Third Class or the servants on the Titanic do not appear at all, and at most the rich of the First Class are addressed with the opulence that now lies at the bottom of the sea. Hardy seems to applaud the iceberg, the 'sinister mate'. In Hardy's mythologising, according to Brown, the iceberg provides retribution by giving the ship and those who perished what they deserve.[57]

Hardy, an otherwise sympathetic author who lost two friends on the Titanic,[58] did not write the poem at a great distance from the disaster, for the first manuscript is dated 24 April 1912 (nine days after the sinking). On 14 May, a matinée was held at Covent Garden in London to raise money for the bereaved, and Hardy wrote The Convergence of the Twain for the occasion. Emerson Brown Jr. wonders if the bereaved, who had just lost their loved ones, could appreciate Hardy's witty allusions – his ruthless artistry.[59]

Folk and pop culture[edit]

There are numerous allusions to the Titanic and its iceberg in American folk culture. In a song by the Dixon Brothers (1938), a band of cotton mill workers from South Carolina, the iceberg not only slashes the side of the ship but also cuts off the Titanic's pride.[60] A more recent example is a song by the Mrs. Ackroyd Band (1999), in which a sad polar bear asks for news about the iceberg on which his family has been living.[61]

After all, the iceberg appears with or without the Titanic in many popular representations and contexts, for example as a set of ice cubes in a thematically fitting form.[62] The American comedy format Saturday Night Live had Bowen Yang appear as "The Iceberg that sank the Titanic" in 2021. The sketch deals with the inappropriate reaction of celebrities to scandals. The "Iceberg" sees himself as the one under attack, blames the ship, the ocean and the shipping company, reduces the number of victims to 20 to 30 and promotes his new music album.[63][64]

Museal and miscellaneous[edit]

A place of remembrance for the Titanic is the former site of the Harland & Wolff shipyard that built her. Among other things, Titanic Belfast, a conference centre and museum, opened on the redeveloped site in the 2012 anniversary year. Local editor Tony Canavan regrets that looking at Titanic Belfast reminds him of the appearance of an iceberg.[65] (In fact, the building is meant to reflect the collision of iceberg and ship).[66]

There is no memorial for the iceberg in the strict sense; it rarely appears on commemorative plaques. In Red Rocks Park (near Denver, Colorado) there are two rocks named Sinking Titanic and Iceberg.[67]

Large iceberg dummies can be seen at the Titanic museum in Branson, Missouri and the one in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee. They are located outside on the buildings, each of which is modelled on the appearance of the Titanic.

In the museum in Pigeon Forge there is a large ice installation to touch (4.6 by 8.5 metres). It is meant to make the coldness of an iceberg tangible. In August 2021, there was an accident: the ice wall collapsed, injuring three visitors and sending them to a hospital.[68][69][70]

The Northland Discovery Boat Tours offer boat tours off the coast of Newfoundland. When his boat approaches an iceberg, boatman Paul Alcock plays the theme music from the 1997 Titanic movie. Some tourists laugh about it, others are moved. The icebergs are the most important reason for someone to go on his tour, he says. Lorraine McGrath from the tourism promotion board of the city of St. John's in Newfoundland talks about the fascination that icebergs exert on those who see one for the first time. She is often asked by tourists, 'Is that the iceberg that sank the Titanic?' She replies in a good-humored manner, 'No, dear. That's a different one.'[71]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Three nautical miles equals 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi).

References[edit]

- ^ a b Olson, Donald W.; Doescher, Russell L.; Sinnott, Roger W. (April 2012). "Did the Moon Sink the Titanic?" (PDF). Sky and Telescope. pp. 34–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-02-20. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ Grant R. Bigg, David J. Wilton: Iceberg risk in the Titanic year of 1912: was it exceptional? In: Weather – April 2014, Vol. 69, No. 4, pp. 100–104, see p. 103.

- ^ Nadja Podbregar (2014-04-11). "Neues zum Titanic-Eisberg". Bild der Wissenschaft (in German). Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ Megan E. Linkin: Icebergs Ahead!: How Weather Doomed The Titanic. In: Weatherwise, volume 60, no. 5, pp. 20–25, see p. 24/25. DOI:10.3200/WEWI.60.5.20-25

- ^ Alasdair Wilkins (2012-04-15). "Whatever happened to the iceberg that sank the Titanic?". gizmodo. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ^ Daniel Stone (2022-08-16). "The Incredible Story of the Iceberg That Sank the Titanic". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 389, fn. 250.

- ^ a b Halpern 2016, p. 81.

- ^ Halpern 2016, p. 81/82.

- ^ Frances Wilson: How to Survive the Titanic, or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay. Harper Perennial, New York 2012, chapter 7.

- ^ Frances Wilson: How to Survive the Titanic, or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay. Harper Perennial, New York 2012, Kap. 7.

- ^ a b Halpern 2016, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Walter Lord: The Night Lives On: The Untold Stories and Secrets Behind the Sinking of the "Unsinkable" Ship Titanic. Morrow, 1986, Kap. 6.

- ^ Halpern 2016, p. 84/85, 88.

- ^ Halpern 2016, p. 85.

- ^ Halpern 2016, p. 90.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 293.

- ^ Statements 2439–2443, British inquiry, last seen 1 September 2023.

- ^ Ed Darack: Titanic's Mirage: A New Perspective on One of History's Greates Mysteries. In: Weatherwise, 66:2, pp. 24-31, DOI:10.1080/00431672.2013.762839, see p. 30.

- ^ a b Fitch et al 2015, p. 143.

- ^ Day 7, American inquiry, last seen 1 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Fitch et al 2015, p. 144.

- ^ American inquiry

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 149.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 144, 151.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 157, 168.

- ^ a b c Fitch et al 2015, p. 151.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 153.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 146/147.

- ^ a b Fitch et al 2015, p. 166.

- ^ a b Fitch et al 2015, p. 157.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 161, 166.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Grant R. Bigg, David J. Wilton: Iceberg risk in the Titanic year of 1912: was it exceptional? In: Weather – April 2014, Vol. 69, No. 4, p. 100–104, see p. 102.

- ^ a b David Bressan (2017-04-12). "The Climate Science Behind The Sinking Of The Titanic". Forbes. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- ^ Fitch et al 2015, p. 283.

- ^ Charles Weeks, Samuel Halpern: Description of the damage to the ship. In: Samuel Halpern (Hrsg.): Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. The History Press, Stroud 2016 (2012), p. 100–130, see p. 45.

- ^ Grant R. Bigg, David J. Wilton: Iceberg risk in the Titanic year of 1912: was it exceptional? In: Weather – April 2014, Vol. 69, No. 4, p. 100–104.

- ^ a b Melissa Gray (2015-10-17). "Photograph believed to show 'Titanic Iceberg' up for auction". CNN. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- ^ Matt Mathers (2020-06-15). "Rare photo of iceberg 'most likely' behind sinking of Titanic emerges over 100 years later". Independent. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- ^ Steven Biel: Down with the Old Canoe. A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster. W. W. Norton & Company, New York / London 1996, p. 143.

- ^ Stephen Brown, Pierre McDonagh, Clifford J. Shultz: Titanic: consuming the myths and meanings of an ambiguous brand. In: Journal of Consumer Research 40(4), 2013, p. 595–614, see p. 599.

- ^ Richard Brown: Voyage of the Iceberg: The Story of the Iceberg that Sank the Titanic, 1983. Rezensiert von Philip Morrison, in: Scientific American, volume 250, no. 4 (April 1984), p. 32/33.

- ^ Steven Biel: Down with the Old Canoe. A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster. W. W. Norton & Company, New York / London 1996, p. 69.

- ^ Steven Biel: Down with the Old Canoe. A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster. W. W. Norton & Company, New York / London 1996, p. 129.

- ^ Peter Krämer: Women First: "Titanic' (1997), action-adventure films and Hollywood's female audience. In: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, volume 18, no. 4, p. 599–618.

- ^ Stephen Brown, Pierre McDonagh, Clifford J. Shultz: Titanic: consuming the myths and meanings of an ambiguous brand. In: Journal of Consumer Research 40(4), 2013, p. 595–614, see p. 606.

- ^ Richard Rankin Russell: Exorcising the Ghosts of Conflict in Northern Ireland: Stewart Parker's The Iceberg and Pentecost. In: Eire-Ireland, volume 41, no. 3/4 Fall/Wint 2006, p. 42–58, see p. 43/44.

- ^ Fran Brearton: Dancing Unto Death: Perceptions of the Somme, the Titanic and Ulster Protestantism. In: The Irish Review (Cork), Winter-Spring, 1997, no. 20, p. 89–103, see p. 99.

- ^ Lilia Shevtsova: Russia under Putin: Titanic looking for its iceberg? In: Communist and Post-Communist Studies 45 (2012), p. 209–216.

- ^ Matthew H. Birkhold: Consuming Icebergs in the Anthropocene. In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Oktober-Dezember 2020, 46. Jahrgang, Heft 4 [Writing History in the Anthropocene], pp. 662–681, see p. 675.

- ^ Thomas Hardy. "The Convergence of the Twain". poetryfoundation.org. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- ^ "The Convergence of the Twain (Lines on the loss of the 'Titanic')" (PDF). The Thomas Hardy Society. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ a b Meredith Bergmann (2012-10-26). ""The Convergence of the Twain". Thomas Hardy and Popular Sentiment". Contemporary Literary Review. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Emerson Brown Jr.: Ruthless Artistry of Hardy's "Convergence of the Twain". In: The Sewanee Review, Frühling 1994, volume 102, no. 2 (Spring 1994), p. 233–243, see p. 233/234.

- ^ Emerson Brown Jr.: Ruthless Artistry of Hardy's "Convergence of the Twain." In: The Sewanee Review, Frühling 1994, volume 102, no. 2 (Spring 1994), p. 233–243, see p. 234–236.

- ^ Emerson Brown Jr.: Ruthless Artistry of Hardy's "Convergence of the Twain." In: The Sewanee Review, Frühling 1994, volume 102, no. 2 (Spring 1994), p. 233–243, see p. 237.

- ^ Tracy Hayes. "Hardy and the Titanic". The Thomas Hardy Society. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Emerson Brown Jr.: Ruthless Artistry of Hardy's "Convergence of the Twain." In: The Sewanee Review, Frühling 1994, volume 102, no. 2 (Spring 1994), p. 233–243, see p. 239/240.

- ^ Steven Biel: Down with the Old Canoe. A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster. W. W. Norton & Company, New York / London 1996, p. 98–100.

- ^ Joseph Scanlon, Allison Vandervalk, Mattea Chadwick-Shubat: Challenge to the Lord: Folk Songs About the "Unsinkable" Titanic. In: Canadian Folk Music. volume 45, no. 3, p. 3–10, see p. 1/2.

- ^ "FOOD FUN: The Titanic As An Ice Cube". The Nibble. 2019-03-17. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ Lauren Edmonds (2021-05-23). "Bowen Yang reveals how his viral 'Iceberg That Sank The Titanic' SNL sketch made it to air". businessinsider.nl. Retrieved 2023-09-02.

- ^ Alisha Grauso (2021-04-11). "SNL's Titanic Iceberg Sketch Mocks Celebrity Cancel Culture Reaction". Screen Rant. Retrieved 2023-09-02.

- ^ Tony Canavan: Titanic: Sinking in a Sea of Hype? In: History Ireland. May/June 2012, volume 20, no. 3, p. 10/11.

- ^ Linda Stewart (2012-07-25). "Is Titanic building really a carbuncle on the skyline?". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ Andrew Wojtanik (2017-12-30). "Trading Post Trail (Red Rocks Park, CO)". Live And Let Hike. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Martin Belam (2021-08-04). "Visitors to US Titanic museum injured by replica iceberg". The Guardian. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ Travis Dorman. "Titanic museum iceberg wall collapses in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, injuring 3 visitors". USA Today. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ David Williams (2021-08-03). "Titanic museum iceberg wall collapses, injuring 3 visitors". CNN. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ Ian Stalker: Titanic Business. In: Americas. April 2008, volume 60, no. 2, p. 2/3.

- Sources

- Fitch, Tad and J. Kent Layton, Bill Wormstedt: On a Sea of Glass. The Life & Loss of the RMS Titanic. Amberley, Stroud 2015

- Halpern, Samuel. Account of the Ship's Journey across the Atlantic. In: Samuel Halpern (Hrsg.): Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. The History Press, Stroud 2016 (2012), pp. 71–89, see

External links[edit]

- The Iceberg That Sank the Titanic (BBC)

- The Iceberg – Resurfaced? (Encyclopedia Titanica)

- "The Incredible Story of the Iceberg That Sank the Titanic" (Smithsonian Magazine)