Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia | |

|---|---|

| State of Georgia | |

| Nickname(s): Peach State; Empire State of the South | |

| Motto(s): "Wisdom, Justice & Moderation"[1] | |

| Anthem: "Georgia on My Mind" | |

Map of the United States with Georgia highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of Georgia |

| Admitted to the Union | January 2, 1788 (4th) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Atlanta |

| Largest county or equivalent | Fulton |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Atlanta |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Brian Kemp (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Burt Jones (R) |

| Legislature | Georgia General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Georgia |

| U.S. senators |

|

| U.S. House delegation | 9 Republicans 5 Democrats (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 59,425 sq mi (153,909 km2) |

| • Land | 57,906 sq mi (149,976 km2) |

| • Water | 1,519 sq mi (3,933 km2) 2.6% |

| • Rank | 24th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 298 mi (480 km) |

| • Width | 230 mi (370 km) |

| Elevation | 600 ft (180 m) |

| Highest elevation | 4,784 ft (1,458 m) |

| Lowest elevation (Atlantic Ocean[2]) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Total | 11,029,227[3] |

| • Rank | 8th |

| • Density | 185.2/sq mi (71.5/km2) |

| • Rank | 18th |

| • Median household income | $61,200[4] |

| • Income rank | 29th |

| Demonym | Georgian |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | English Spanish (7.42%) Other (2.82%) |

| Time zone | UTC– 05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC– 04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | GA |

| ISO 3166 code | US-GA |

| Traditional abbreviation | Ga. |

| Latitude | 30.356–34.985° N |

| Longitude | 80.840–85.605° W |

| Website | georgia |

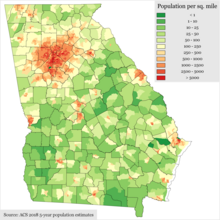

Georgia is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the northwest, North Carolina to the north, South Carolina to the northeast, Florida to the south, and Alabama to the west. Of the 50 United States, Georgia is the 24th-largest by area and 8th most populous. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, its 2023 estimated population was 11,029,227.[3] Atlanta, a global city, is both the state's capital and its largest city. The Atlanta metropolitan area, with a population of more than 6.3 million people in 2023, is the 6th most populous metropolitan area in the United States and contains about 57% of Georgia's entire population. Other major metropolitan areas in the state include Augusta, Savannah, Columbus, and Macon.[5] Georgia has 100 miles (160 km) of coastline along the Atlantic Ocean.

The Province of Georgia was created in 1732 and first settled in 1733 with the founding of Savannah. Georgia became a British royal colony in 1752. It was the last and southernmost of the original Thirteen Colonies to be established.[6] Named after King George II of Great Britain, the Georgia Colony covered the area from South Carolina south to Spanish Florida and west to French Louisiana at the Mississippi River. On January 2, 1788, Georgia became the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution.[7] From 1802 to 1804, western Georgia was split to form the Mississippi Territory, which later was admitted as the U.S. states of Alabama and Mississippi. Georgia declared its secession from the Union on January 19, 1861, and was one of the original seven Confederate States.[7] Following the Civil War, it was the last state to be restored to the Union, on July 15, 1870.[7] In the post-Reconstruction era of the late 19th century, Georgia's economy was transformed as a group of prominent politicians, businessmen, and journalists, led by Henry W. Grady, espoused the "New South" philosophy of sectional reconciliation and industrialization.[8] During the mid-20th century, several people from Georgia, most notably Martin Luther King Jr., were prominent leaders during the civil rights movement.[7] Atlanta was selected as host of the 1996 Summer Olympics, which marked the 100th anniversary of the modern Olympic Games. Since 1945, Georgia has seen substantial population and economic growth as part of the broader Sun Belt phenomenon. From 2007 to 2008, 14 of Georgia's counties ranked among the nation's 100 fastest-growing.[9]

Georgia is defined by a diversity of landscapes, flora, and fauna. The state's northernmost regions include the Blue Ridge Mountains, part of the larger Appalachian Mountain system. The Piedmont plateau extends from the foothills of the Blue Ridge south to the Fall Line, an escarpment to the Coastal Plain defining the state's southern region. Georgia's highest point is Brasstown Bald at 4,784 feet (1,458 m) above sea level; the lowest is the Atlantic Ocean. With the exception of some high-altitude areas in the Blue Ridge, the entirety of the state has a humid subtropical climate. Of the states entirely east of the Mississippi River, Georgia is the largest in land area.[10]

History[edit]

Before settlement by Europeans, Georgia was inhabited by the mound building cultures. The Province of Georgia was founded by General James Oglethorpe at Savannah on February 12, 1733, a year after its creation as a new British colony.[11] It was administered by the Trustees for the Establishment of the Colony of Georgia in America under a charter issued by (and named for) King George II. The Trustees implemented an elaborate plan for the colony's settlement, known as the Oglethorpe Plan, which envisioned an agrarian society of yeoman farmers and prohibited slavery. The colony was invaded by the Spanish in 1742, during the War of Jenkins' Ear. In 1752, after the government failed to renew subsidies that had helped support the colony, the Trustees turned over control to the crown. Georgia became a crown colony, with a governor appointed by the king.[12]

The Province of Georgia was one of the Thirteen Colonies that revolted against British rule in the American Revolution by signing the 1776 Declaration of Independence. The State of Georgia's first constitution was ratified in February 1777. Georgia was the 10th state to ratify the Articles of Confederation on July 24, 1778,[13] and was the 4th state to ratify the United States Constitution on January 2, 1788.[14]

After the Creek War (1813–1814), General Andrew Jackson forced the Muscogee (Creek) tribes to surrender land to the state of Georgia, including in the Treaty of Fort Jackson (1814), surrendering 21 million acres in what is now southern Georgia and central Alabama, and the Treaty of Indian Springs (1825).[15] In 1829, gold was discovered in the North Georgia mountains leading to the Georgia Gold Rush and establishment of a federal mint in Dahlonega, which continued in operation until 1861. The resulting influx of white settlers put pressure on the government to take land from the Cherokee Nation. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, sending many eastern Native American nations to reservations in present-day Oklahoma, including all of Georgia's tribes. Despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) that U.S. states were not permitted to redraw Indian boundaries, President Jackson and the state of Georgia ignored the ruling. In 1838, his successor, Martin Van Buren, dispatched federal troops to gather the tribes and deport them west of the Mississippi. This forced relocation, known as the Trail of Tears, led to the death of more than four thousand Cherokees.

In early 1861, Georgia joined the Confederacy (with secessionists having a slight majority of delegates)[16] and became a major theater of the Civil War. Major battles took place at Chickamauga, Kennesaw Mountain, and Atlanta. In December 1864, a large swath of the state from Atlanta to Savannah was destroyed during General William Tecumseh Sherman's March to the Sea. 18,253 Georgian soldiers died in service, roughly one of every five who served.[17] In 1870, following the Reconstruction era, Georgia became the last Confederate state to be restored to the Union.

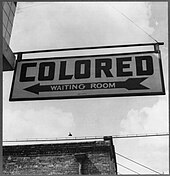

With white Democrats having regained power in the state legislature, they passed a poll tax in 1877, which disenfranchised many poor black (and some white) people, preventing them from registering.[18] In 1908, the state established a white primary; with the only competitive contests within the Democratic Party, it was another way to exclude black people from politics.[19] They constituted 46.7% of the state's population in 1900, but the proportion of Georgia's population that was African American dropped thereafter to 28%, primarily due to tens of thousands leaving the state during the Great Migration.[20] According to the Equal Justice Initiative's 2015 report on lynching in the United States (1877–1950), Georgia had 531 deaths, the second-highest total of these extralegal executions of any state in the South. The overwhelming number of victims were black and male.[21] Political disfranchisement persisted through the mid-1960s, until after Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

An Atlanta-born Baptist minister who was part of the educated middle class that had developed in Atlanta's African-American community, Martin Luther King Jr., emerged as a national leader in the civil rights movement. King joined with others to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Atlanta in 1957 to provide political leadership for the Civil Rights Movement across the South. The civil rights riots of the 1956 Sugar Bowl would also take place in Atlanta after a clash between Georgia Tech's president Blake R. Van Leer and Governor Marvin Griffin.[22]

On February 5, 1958, during a training mission flown by a B-47, a Mark 15 nuclear bomb, also known as the Tybee Bomb, was lost off the coast of Tybee Island near Savannah. The bomb was thought by the Department of Energy to lie buried in silt at the bottom of Wassaw Sound.[23]

By the 1960s, the proportion of African Americans in Georgia had declined to 28% of the state's population, after waves of migration to the North and some immigration by whites.[20] With their voting power diminished, it took some years for African Americans to win a state-wide office. Julian Bond, a noted civil rights leader, was elected to the state House in 1965, and served multiple terms there and in the state senate.

Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. testified before Congress in support of the Civil Rights Act, and Governor Carl Sanders worked with the Kennedy administration to ensure the state's compliance. Ralph McGill, editor and syndicated columnist at the Atlanta Constitution, earned admiration by writing in support of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1970, newly elected Governor Jimmy Carter declared in his inaugural address that the era of racial segregation had ended. In 1972, Georgians elected Andrew Young to Congress as the first African American Congressman since the Reconstruction era.

In 1980, construction was completed on an expansion of what is now named Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL). The busiest and most efficient airport in the world, it accommodates more than a hundred million passengers annually.[24] Employing more than 60,000 people, the airport became a major engine for economic growth.[24] With the advantages of cheap real estate, low taxes, right-to-work laws and a regulatory environment limiting government interference, the Atlanta metropolitan area became a national center of finance, insurance, technology, manufacturing, real estate, logistics, and transportation companies, as well as the film, convention, and trade show businesses. As a testament to the city's growing international profile, in 1990 the International Olympic Committee selected Atlanta as the site of the 1996 Summer Olympics. Taking advantage of Atlanta's status as a transportation hub, in 1991 UPS established its headquarters in the suburb of Sandy Springs. In 1992, construction finished on Bank of America Plaza, the tallest building in the U.S. outside of New York or Chicago.

Geography[edit]

Boundaries[edit]

Beginning from the Atlantic Ocean, the state's eastern border with South Carolina runs up the Savannah River, northwest to its origin at the confluence of the Tugaloo and Seneca Rivers. It then continues up the Tugaloo (originally Tugalo) and into the Chattooga River, its most significant tributary. These bounds were decided in the 1797 Treaty of Beaufort, and tested in the U.S. Supreme Court in the two Georgia v. South Carolina cases in 1923 and 1989.[citation needed]

The border then takes a sharp turn around the tip of Rabun County, at latitude 35°N, though from this point it diverges slightly south (due to inaccuracies in the original survey, conducted in 1818).[25] This northern border was originally the Georgia and North Carolina border all the way to the Mississippi River, until Tennessee was divided from North Carolina, and the Yazoo companies induced the legislature of Georgia to pass an act, approved by the governor in 1795, to sell the greater part of Georgia's territory presently comprising Alabama and Mississippi.[26]

The state's western border runs in a straight line south-southeastward from a point southwest of Chattanooga, to meet the Chattahoochee River near West Point. It continues downriver to the point where it joins the Flint River (the confluence of the two forming Florida's Apalachicola River); the southern border goes almost due east and very slightly south, in a straight line to the St. Mary's River, which then forms the remainder of the boundary back to the ocean.[citation needed]

The water boundaries are still set to be the original thalweg of the rivers. Since then, several have been inundated by lakes created by dams, including the Apalachicola/Chattahoochee/Flint point now under Lake Seminole.[citation needed]

An 1818 survey erroneously placed Georgia's border with Tennessee one mile (1.6 km) south of the intended location of the 35th parallel north.[25] State legislators still dispute this placement, as correction of this inaccuracy would allow Georgia access to water from the Tennessee River.[27]

Geology and terrain[edit]

Georgia consists of five principal physiographic regions: The Cumberland Plateau, Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, Blue Ridge Mountains, Piedmont, and the Atlantic coastal plain.[28] Each region has its own distinctive characteristics. For instance, the region, which lies in the northwest corner of the state, includes limestone, sandstone, shale, and other sedimentary rocks, which have yielded construction-grade limestone, barite, ocher, and small amounts of coal.

Ecology[edit]

The state of Georgia has approximately 250 tree species and 58 protected plants. Georgia's native trees include red cedar, a variety of pines, oaks, hollies, cypress, sweetgum, scaly-bark and white hickories, and sabal palmetto. East Georgia is in the subtropical coniferous forest biome and conifer species as other broadleaf evergreen flora make up the majority of the southern and coastal regions. Yellow jasmine and mountain laurel make up just a few of the flowering shrubs in the state.

White-tailed deer are found in nearly all counties of Georgia. The northern mockingbird and brown thrasher are among the 160 bird species that live in the state.

Reptiles include the eastern diamondback, copperhead, and cottonmouth snakes as well as alligators; amphibians include salamanders, frogs and toads. There are about 79 species of reptile and 63 amphibians known to live in Georgia. The Argentine black and white tegu is currently an invasive species in Georgia. It poses a problem to local wildlife by chasing down and killing many native species and dominating habitats.[29]

The most popular freshwater game fish are trout, bream, bass, and catfish, all but the last of which are produced in state hatcheries for restocking. Popular saltwater game fish include red drum, spotted seatrout, flounder, and tarpon. Porpoises, whales, shrimp, oysters, and blue crabs are found inshore and offshore of the Georgia coast.

Climate[edit]

The majority of the state is primarily a humid subtropical climate. Hot and humid summers are typical, except at the highest elevations. The entire state, including the North Georgia mountains, receives moderate to heavy precipitation, which varies from 45 inches (1,100 mm) in central Georgia[30] to approximately 75 inches (1,900 mm) around the northeast part of the state.[31] The degree to which the weather of a certain region of Georgia is subtropical depends on the latitude, its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean or Gulf of Mexico, and the elevation. The latter factor is felt chiefly in the mountainous areas of the northern part of the state, which are farther away from the ocean and can be 4,500 feet (1,400 m) above sea level. The USDA plant hardiness zones for Georgia range from zone 6b (no colder than −5 °F (−21 °C)) in the Blue Ridge Mountains to zone 8b (no colder than 15 °F (−9 °C) ) along the Atlantic coast and Florida border.[32]

The highest temperature ever recorded is 112 °F (44 °C) in Louisville on July 24, 1952,[33] while the lowest is −17 °F (−27 °C) in northern Floyd County on January 27, 1940.[34] Georgia is one of the leading states in frequency of tornadoes, though they are rarely stronger than EF1. Although tornadoes striking the city are very rare,[35] an EF2 tornado[35] hit downtown Atlanta on March 14, 2008, causing moderate to severe damage to various buildings. With a coastline on the Atlantic Ocean, Georgia is also vulnerable to hurricanes, although direct hurricane strikes were rare during the 20th century. Georgia often is affected by hurricanes that strike the Florida Panhandle, weaken over land, and bring strong tropical storm winds and heavy rain to the interior, a recent example being Hurricane Michael,[36] as well as hurricanes that come close to the Georgia coastline, brushing the coast on their way north without ever making landfall. Hurricane Matthew of 2016 and Hurricane Dorian of 2019 did just that.

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athens | 51/11 33/1 |

56/13 35/2 |

65/18 42/6 |

73/23 49/9 |

80/27 58/14 |

87/31 65/18 |

90/32 69/21 |

88/31 68/20 |

82/28 63/17 |

73/23 51/11 |

63/17 42/6 |

54/12 35/2 |

| Atlanta | 52/11 34/1 |

57/14 36/2 |

65/18 44/7 |

73/23 50/10 |

80/27 60/16 |

86/30 67/19 |

89/32 71/22 |

88/31 70/21 |

82/28 64/18 |

73/23 53/12 |

63/17 44/7 |

55/13 36/2 |

| Augusta | 56/13 33/1 |

61/16 36/4 |

69/21 42/6 |

77/25 48/9 |

84/29 57/14 |

90/32 65/18 |

92/33 70/21 |

90/32 68/20 |

85/29 62/17 |

76/24 50/10 |

68/20 41/5 |

59/15 35/2 |

| Columbus | 57/14 37/3 |

62/17 39/4 |

69/21 46/8 |

76/24 52/11 |

83/28 61/16 |

90/32 69/21 |

92/33 72/22 |

91/32 72/22 |

86/30 66/19 |

77/25 54/12 |

68/20 46/8 |

59/15 39/4 |

| Macon | 57/14 34/1 |

61/16 37/3 |

68/20 44/7 |

76/24 50/10 |

83/28 59/15 |

90/32 67/19 |

92/33 70/21 |

90/32 70/21 |

85/29 64/18 |

77/25 51/11 |

68/20 42/6 |

59/15 36/2 |

| Savannah | 60/16 38/3 |

64/18 41/5 |

71/22 48/9 |

78/26 53/12 |

84/29 61/16 |

90/32 68/20 |

92/33 72/22 |

90/32 71/22 |

86/30 67/19 |

78/26 56/13 |

70/21 47/8 |

63/17 40/4 |

| Temperatures are given in °F/°C format, with highs on top of lows.[37] | ||||||||||||

Due to anthropogenic climate change, the climate of Georgia is warming. This is already causing major disruption, for example, from sea level rise (Georgia is more vulnerable to it than many other states because its land is sinking) and further warming will increase it.[38][39][40][41]

Major cities[edit]

Atlanta, located in north-central Georgia at the Eastern Continental Divide, has been Georgia's capital city since 1868. It is the most populous city in Georgia, with a 2020 U.S. census population of just over 498,000.[42] The state has seventeen cities with populations over 50,000, based on official 2020 U.S. census data.[42]

Along with the rest of the Southeast, Georgia's population continues to grow rapidly, with primary gains concentrated in urban areas. The U.S. Census Bureau lists fourteen metropolitan areas in the state. The population of the Atlanta metropolitan area added 1.23 million people (24%) between 2000 and 2010, and Atlanta rose in rank from the eleventh-largest metropolitan area in the United States to the ninth-largest.[43] The Atlanta metropolitan area is the cultural and economic center of the Southeast; its official population in 2020 was over 6 million, or 57% of Georgia's total population.[44]

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Atlanta  Columbus |

1 | Atlanta | Fulton, DeKalb | 498,715 |  Augusta Macon | ||||

| 2 | Columbus | Muscogee | 206,922 | ||||||

| 3 | Augusta | Richmond | 202,081 | ||||||

| 4 | Macon | Bibb | 157,346 | ||||||

| 5 | Savannah | Chatham | 147,780 | ||||||

| 6 | Athens | Clarke | 127,315 | ||||||

| 7 | Sandy Springs | Fulton | 108,080 | ||||||

| 8 | South Fulton | Fulton | 107,436 | ||||||

| 9 | Roswell | Cobb, Fulton | 92,833 | ||||||

| 10 | Johns Creek | Fulton | 82,453 | ||||||

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 82,548 | — | |

| 1800 | 162,686 | 97.1% | |

| 1810 | 251,407 | 54.5% | |

| 1820 | 340,989 | 35.6% | |

| 1830 | 516,823 | 51.6% | |

| 1840 | 691,392 | 33.8% | |

| 1850 | 906,185 | 31.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,057,286 | 16.7% | |

| 1870 | 1,184,109 | 12.0% | |

| 1880 | 1,542,181 | 30.2% | |

| 1890 | 1,837,353 | 19.1% | |

| 1900 | 2,216,331 | 20.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,609,121 | 17.7% | |

| 1920 | 2,895,832 | 11.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,908,506 | 0.4% | |

| 1940 | 3,123,723 | 7.4% | |

| 1950 | 3,444,578 | 10.3% | |

| 1960 | 3,943,116 | 14.5% | |

| 1970 | 4,589,575 | 16.4% | |

| 1980 | 5,463,105 | 19.0% | |

| 1990 | 6,478,216 | 18.6% | |

| 2000 | 8,186,453 | 26.4% | |

| 2010 | 9,687,653 | 18.3% | |

| 2020 | 10,711,908 | 10.6% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 11,029,227 | 3.0% | |

| 1910–2022[45][46] | |||

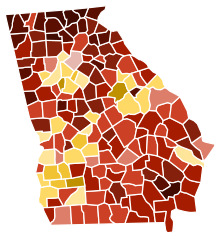

Non-Hispanic White 30–40%40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%90%+Black or African American 40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%

The United States Census Bureau reported Georgia's official population to be 10,711,908 as of the 2020 United States census. This was an increase of 1,024,255, or 10.57% over the 2010 figure of 9,687,653 residents.[47] Immigration resulted in a net increase of 228,415 people, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 378,258 people.[when?]

As of 2010[update], the number of illegal immigrants living in Georgia more than doubled to 480,000 from January 2000 to January 2009, according to a federal report. That gave Georgia the greatest percentage increase among the 10 states with the biggest undocumented immigrant populations during those years.[48] Georgia has banned sanctuary cities.[49]

In 2018, The top countries of origin for Georgia's immigrants were Mexico, India, Jamaica, Korea, and Guatemala.[50]

There were 743,000 veterans in 2009.[51]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 10,689 homeless people in Georgia.[52][53]

Race and ethnicity[edit]

| Race and ethnicity[54] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 50.1% | 53.2% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 30.6% | 32.3% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[b] | — | 10.5% | ||

| Asian | 4.4% | 5.2% | ||

| Native American | 0.2% | 1.5% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.5% | 1.2% | ||

| Racial composition | 1990[55] | 2000[56] | 2010[57] | 2020[58] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 71.0% | 65.1% | 59.7% | 51.9% |

| Black | 27.0% | 28.7% | 30.5% | 31.0% |

| Asian | 1.2% | 2.1% | 3.3% | 4.5% |

| Native | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.5% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

— | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other race | 0.6% | 2.4% | 4.0% | 5.2% |

| Two or more races | — | 1.4% | 2.1% | 6.9% |

In the 1980 census, 1,584,303 people from Georgia claimed English ancestry out of a total state population of 3,994,817, making them 40% of the state, and the largest ethnic group at the time.[59] Today, many of these same people claiming they are of "American" ancestry are actually of English descent, and some are of Scots-Irish descent; however, their families have lived in the state for so long, in many cases since the colonial period, that they choose to identify simply as having "American" ancestry or do not in fact know their own ancestry. Their ancestry primarily goes back to the original thirteen colonies and for this reason many of them today simply claim "American" ancestry, though they are of predominantly English ancestry.[60][61][62][63]

Historically, about half of Georgia's population was composed of African Americans who, before the American Civil War, were almost exclusively enslaved. The Great Migration of hundreds of thousands of blacks from the rural South to the industrial North from 1914 to 1970 reduced the African American population.[64]

Georgia had the second-fastest-growing Asian population growth in the U.S. from 1990 to 2000, more than doubling in size during the ten-year period.[65] Indian people and Chinese people are the largest Asian groups in Georgia.[66] In addition, according to census estimates, Georgia ranks third among the states in terms of the percent of the total population that is African American (after Mississippi and Louisiana) and third in numeric Black population after New York and Florida. Georgia also has a sizeable Latino population. Many are of Mexican descent.[67]

Georgia is the state with the third-lowest percentage of older people (65 or older), at 12.8 percent (as of 2015[update]).[68]

The colonial settlement of large numbers of Scottish American, English American and Scotch-Irish Americans in the mountains and Piedmont, and coastal settlement by some English Americans and African Americans, have strongly influenced the state's culture in food, language and music. The concentration of African slaves repeatedly "imported" to coastal areas in the 18th century from rice-growing regions of West Africa led to the development of Gullah-Geechee language and culture in the Low Country among African Americans. They share a unique heritage in which many African traditions of food, religion and culture were retained. In the creolization of Southern culture, their foodways became an integral part of Low Country cooking.[69][70] Sephardic Jews, French-speaking Swiss people, Moravians, Irish convicts, Piedmont Italians and Russian people immigrated to the state during the colonial era.[71]

As of 2011[update], 58.8% of Georgia's population younger than 1 were minorities (meaning they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white) compared to other states like California with 75.1%, Texas with 69.8%, and New York with 55.6%.[72]

The largest European ancestry groups as of 2011 were: English 8.1%, Irish 8.1%,[73] and German 7.2%.[74]

Languages[edit]

| Language | Speakers (as of 2021[update])[75] | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| English | 8,711,102 | 85.62% |

| Spanish | 795,646 | 7.82% |

| Vietnamese | 57,795 | 0.57% |

| Chinese | 55,024 | 0.54% |

| Korean | 52,742 | 0.52% |

| French | 33,248 | 0.33% |

| Hindi | 31,531 | 0.31% |

| German | 25,881 | 0.25% |

| Haitian | 25,032 | 0.25% |

| Arabic | 21,795 | 0.21% |

As of 2021[update], 85.62% (8,711,102) of Georgia residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 7.82% (795,646) spoke Spanish, and 6.55% (666,849) spoke languages other than English or Spanish at home, with the most common of which were Vietnamese, Chinese, and Korean. In total, 14.38% (1,462,495) of Georgia's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[75]

Religion[edit]

According to the Pew Research Center, the composition of religious affiliation in Georgia was 70% Protestant, 9% Catholic, 1% Mormon, 1% Jewish, 0.5% Muslim, 0.5% Buddhist, and 0.5% Hindu. Atheists, deists, agnostics, and other unaffiliated people make up 13% of the population.[77] Overall, Christianity was the dominant religion in the state, as part of the Bible Belt.

According to the Association of Religion Data Archives in 2010, the largest Christian denominations by number of adherents were the Southern Baptist Convention with 1,759,317; the United Methodist Church with 619,394; and the Roman Catholic Church with 596,384. Non-denominational Evangelical Protestant had 566,782 members, the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee) has 175,184 members, and the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. has 172,982 members.[78] The Presbyterian Church (USA) is the largest Presbyterian body in the state, with 300 congregations and 100,000 members. The other large body, Presbyterian Church in America, had at its founding date 14 congregations and 2,800 members; in 2010 it counted 139 congregations and 32,000 members.[78][79] The Roman Catholic Church is noteworthy in Georgia's urban areas, and includes the Archdiocese of Atlanta and the Diocese of Savannah. Georgia is home to the second-largest Hindu temple in the United States, the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Atlanta, located in the suburb city of Lilburn. Georgia is home to several historic synagogues including The Temple (Atlanta), Congregation Beth Jacob (Atlanta), and Congregation Mickve Israel (Savannah). Chabad and the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute are also active in the state.[80][81]

By the 2022 Public Religion Research Institute's study, 71% of the population were Christian; throughout its Christian population, 60% were Protestant and 8% were Catholic. Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormons collectively made up 3% of other Christians according to the study.[82] Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism collectively formed 4% of the state's non-Christian population; New Age spirituality was 2% of the religious population. Approximately 23% of the state was irreligious.[82]

Population percentage of Georgia in the United States 2010: 3.14% 2020: 3.23%

Economy[edit]

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Economy of Georgia (U.S. state). (Discuss) (September 2020) |

Georgia's 2018 total gross state product was $602 billion.[83] For years Georgia as a state has had the highest credit rating by Standard & Poor's (AAA) and is one of only 15 states with a AAA rating.[84] If Georgia were a stand-alone country, it would be the 28th-largest economy in the world, based on data from 2005.[85]

- Total employment 2021

- 4,034,309

- Total employer establishments 2021

- 253,729[86]

There are 16 Fortune 500 companies and 26 Fortune 1000 companies with headquarters in Georgia, including Home Depot, UPS, Coca-Cola, TSYS, Delta Air Lines, Aflac, Southern Company, and Elevance Health

Atlanta boasts the world's busiest airport, as measured both by passenger traffic and by aircraft traffic.[87][88] Also, the Port of Savannah is the fourth-largest seaport and fastest-growing container seaport in North America, importing and exporting a total of 2.3 million TEUs per year.[89]

Atlanta has a significant effect on the state of Georgia, the Southeastern United States, and beyond. It has been the site of growth in finance, insurance, technology, manufacturing, real estate, service, logistics, transportation, film, communications, convention and trade show businesses and industries, while tourism is important to the economy. Atlanta is a global city, also called world city or sometimes alpha city or world center, as a city generally considered to be an important node in the global economic system.

For the five years through November 2017, Georgia has been ranked the top state (number 1) in the nation to do business, and has been recognized as number 1 for business and labor climate in the nation, number 1 in business climate in the nation, number 1 in the nation in workforce training and as having a "Best in Class" state economic development agency.[90][91]

In 2016, Georgia had a median annual income per person of between $50,000 and $59,999, which is in inflation-adjusted dollars for 2016. The U.S. median annual income for the entire nation is $57,617. This lies within the range of Georgia's median annual income.[92]

A 2024 study listed Georgia in the top 20 of states for an affordable cost of living.[93]

Agriculture[edit]

Widespread farms produce peanuts, corn, and soybeans across middle and south Georgia. The state is the number one producer of pecans in the world, thanks to Naomi Chapman Woodroof regarding peanut breeding, with the region around Albany in southwest Georgia being the center of Georgia's pecan production. Gainesville in northeast Georgia touts itself as the Poultry Capital of the World. Georgia is in the top five blueberry producers in the United States.[94]

Mining[edit]

Major products in the mineral industry include a variety of clays, stones, sands and the clay palygorskite, known as attapulgite.

Industry[edit]

While many textile jobs moved overseas, there is still a textile industry located around the cities of Rome, Columbus, Augusta, Macon and along the I-75 corridor between Atlanta and Chattanooga, Tennessee. Historically it started along the fall line in the Piedmont, where factories were powered by waterfalls and rivers. It includes the towns of Cartersville, Calhoun, Ringgold and Dalton[95]

In November 2009, the South Korean automaker Kia Corporation began production in Georgia. The first Kia plant built in the U.S., Kia Motors Manufacturing Georgia, is located in West Point. Rivian, an electric vehicle manufacturer, plans to begin production at a facility in Social Circle in 2024.[96]

Industrial products include textiles and apparel, transportation equipment, food processing, paper products, chemicals and products, and electric equipment.

Logistics[edit]

Georgia was ranked the number 2 state for infrastructure and global access by Area Development magazine.[97]

The Georgia Ports Authority owns and operates four ports in the state: Port of Savannah, Port of Brunswick, Port Bainbridge, and Port Columbus. The Port of Savannah is the third-busiest seaport in the United States,[98] importing and exporting a total of 2.3 million TEUs per year.[89] The Port of Savannah's Garden City Terminal is the largest single container terminal in North America.[99] Several major companies including Target, IKEA, and Heineken operate distribution centers in close proximity to the Port of Savannah.

Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport moves over 650,000 tons of cargo annually through three cargo complexes (2 million square feet or 200,000 square meters of floor space). It has nearby cold storage for perishables; it is the only airport in the Southeast with USDA-approved cold-treatment capabilities. Delta Air Lines also offers an on-airport refrigeration facility for perishable cargo, and a 250-acre Foreign Trade Zone is located at the airport.[100]

Georgia is a major railway hub, has the most extensive rail system in the Southeast, and has the service of two Class I railroads, CSX and Norfolk Southern, plus 24 short-line railroads. Georgia is ranked the No. 3 state in the nation for rail accessibility. Rail shipments include intermodal, bulk, automotive and every other type of shipment.[101]

Georgia has an extensive interstate highway system including 1,200 miles (1,900 kilometers) of interstate highway and 20,000 miles (32,000 kilometers) of federal and state highways that facilitate the efficient movement of more than $620 billion of cargo by truck each year. Georgia's six interstates connect to 80 percent of the U.S. population within a two-day truck drive. More than $14 billion in funding has been approved[when?] for new roadway infrastructure.[102]

Military[edit]

Southern Congressmen have attracted major investment by the U.S. military in the state. The several installations include Moody Air Force Base, Fort Stewart, Hunter Army Airfield, Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Fort Moore, Robins Air Force Base, Fort Eisenhower, Marine Corps Logistics Base Albany, Dobbins Air Reserve Base, Coast Guard Air Station Savannah and Coast Guard Station Brunswick. These installations command numerous jobs and business for related contractors.

Energy use and production[edit]

Georgia's electricity generation and consumption are among the highest in the United States, with natural gas being the primary electrical generation fuel, followed by coal. The state also has two nuclear power facilities, Plant Hatch and Plant Vogtle, which contribute almost one fourth of Georgia's electricity generation, and two additional nuclear reactors are being built at Vogtle as of 2022.[citation needed] In 2013, the generation mix was 39% gas, 35% coal, 23% nuclear, 3% hydro and other renewable sources. The leading area of energy consumption is the industrial sector because Georgia "is a leader in the energy-intensive wood and paper products industry".[103] Solar generated energy is becoming more in use with solar energy generators currently installed ranking Georgia 15th in the country in installed solar capacity. In 2013, $189 million was invested in Georgia to install solar for home, business and utility use representing a 795% increase over the previous year.[104]

State taxes[edit]

Georgia has a progressive income tax structure with six brackets of state income tax rates that range from 1% to 6%. In 2009, Georgians paid 9% of their income in state and local taxes, compared to the U.S. average of 9.8% of income.[105] This ranks Georgia 25th among the states for total state and local tax burden.[105] The state sales tax in Georgia is 4%[106] with additional percentages added through local options (e.g. special-purpose local-option sales tax or SPLOST), but there is no sales tax on prescription drugs, certain medical devices, or food items for home consumption.[107]

The state legislature may allow municipalities to institute local sales taxes and special local taxes, such as the 2% SPLOST tax and the 1% sales tax for MARTA serviced counties. Excise taxes are levied on alcohol, tobacco, and motor fuel. Owners of real property in Georgia pay property tax to their county. All taxes are collected by the Georgia Department of Revenue and then properly distributed according to any agreements that each county has with its cities.

Film[edit]

The Georgia Film, Music and Digital Entertainment Office promotes filming in the state.[108] Since 1972, over eight hundred films and 1,500 television shows have been filmed on location in Georgia.[109] Georgia overtook California in 2016 as the state with the most feature films produced on location. In the fiscal year 2017, film and television production in Georgia had an economic impact of $9.5 billion.[110] Atlanta has been called the "Hollywood of the South".[111] Television shows like Stranger Things, The Walking Dead, and The Vampire Diaries are filmed in the state.[112] Movies such as Passengers, Forrest Gump, Contagion, Hidden Figures, Sully, Baby Driver, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Captain America: Civil War, Black Panther, Birds of Prey, and many more, were filmed around Georgia.[113][114]

Tourism[edit]

In the Atlanta area, World of Coke, Georgia Aquarium, Zoo Atlanta and Stone Mountain are important tourist attractions.[115][116] Stone Mountain is Georgia's "most popular attraction"; receiving more than four million tourists per year.[117][118] The Georgia Aquarium, in Atlanta, was the largest aquarium in the world in 2010 according to Guinness World Records.[119]

Callaway Gardens, in western Georgia, is a family resort.[120] The area is also popular with golfers.

The Savannah Historic District attracts more than eleven million tourists each year.[121]

The Golden Isles is a string of barrier islands off the Atlantic coast of Georgia near Brunswick that includes beaches, golf courses and the Cumberland Island National Seashore.

Several sites honor the lives and careers of noted American leaders: the Little White House in Warm Springs, which served as the summer residence of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt while he was being treated for polio; President Jimmy Carter's hometown of Plains and the Carter Presidential Center in Atlanta; the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta, which is the final resting place of Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King; and Atlanta's Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Dr. King preached.

Literature[edit]

Authors have grappled with Georgia's complex history. Popular novels related to this include Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind, Olive Ann Burns' Cold Sassy Tree, and Alice Walker's The Color Purple.

A number of noted authors, poets and playwrights have lived in Georgia, such as James Dickey, Flannery O'Connor, Sidney Lanier, Frank Yerby and Lewis Grizzard.[122]

Television[edit]

Well-known television shows set in Atlanta include, from Tyler Perry Studios, House of Payne and Tyler Perry's Meet the Browns, The Real Housewives of Atlanta, the CBS sitcom Designing Women, Matlock, the popular AMC series The Walking Dead, FX comedy drama Atlanta, Lifetime's Drop Dead Diva, Rectify and numerous HGTV original productions.

The Dukes of Hazzard, a 1980s TV show, was set in the fictional Hazzard County, Georgia. The first five episodes were shot on location in Conyers and Covington, Georgia as well as some locations in Atlanta. Production was then moved to Burbank, California.[citation needed]

Also filmed in Georgia is The Vampire Diaries, using Covington as the setting for the fictional Mystic Falls.

Music[edit]

A number of notable musicians in various genres of popular music are from Georgia. Among them are Ray Charles (whose many hits include "Georgia on My Mind", now the official state song), and Gladys Knight (known for her Georgia-themed song, "Midnight Train to Georgia").

Rock groups from Georgia include the Atlanta Rhythm Section, The Black Crowes, and The Allman Brothers.

The city of Athens sparked an influential rock music scene in the 1980s and 1990s. Among the groups achieving their initial prominence there were R.E.M., Widespread Panic, and the B-52's.

Since the 1990s, various hip-hop and R&B musicians have included top-selling artists such as Outkast, Usher, Ludacris, TLC, B.o.B., and Ciara. Atlanta is mentioned in a number of these artists' tracks, such as Usher's "A-Town Down" reference in his 2004 hit "Yeah!" (which also features Atlanta artists Lil Jon and Ludacris), Ludacris' "Welcome to Atlanta", Outkast's album "ATLiens", and B.o.B.'s multiple references to Decatur, Georgia, as in his hit song "Strange Clouds".

Films set in Georgia[edit]

Two movies, both set in Atlanta, won Oscars for Best Picture: Gone with the Wind (1939) and Driving Miss Daisy (1989). Other films set in Georgia include Deliverance (1972), Parental Guidance (2012), and Vacation (2015).

Sports[edit]

Sports in Georgia include professional teams in nearly all major sports, Olympic Games contenders and medalists, collegiate teams in major and small-school conferences and associations, and active amateur teams and individual sports. The state of Georgia has teams in four major professional leagues—the Atlanta Braves of Major League Baseball, the Atlanta Falcons of the National Football League, the Atlanta Hawks of the National Basketball Association, and Atlanta United FC of Major League Soccer.

The Georgia Bulldogs (Southeastern Conference), Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets (Atlantic Coast Conference), Georgia State Panthers and Georgia Southern Eagles (Sun Belt Conference) are Georgia's NCAA Division I FBS football teams, having won multiple national championships between them. The Georgia Bulldogs and the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets have a historical rivalry in college football known as Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate, and the Georgia State Panthers and the Georgia Southern Eagles have recently developed their own rivalry.

The 1996 Summer Olympics took place in Atlanta. The stadium that was built to host various Olympic events was converted to Turner Field, home of the Atlanta Braves through 2016. Atlanta will serve as a host city for the 2026 FIFA World Cup.[123]

The Masters golf tournament, the first of the PGA Tour's four "majors", is held annually the second weekend of April at the Augusta National Golf Club.

The RSM Classic is a golf tournament on the PGA Tour, played in the autumn in Saint Simons Island, Georgia.[citation needed][importance?]

The Atlanta Motor Speedway hosts the Dixie 500 NASCAR Cup Series stock car race and Road Atlanta the Petit Le Mans endurance sports car race.

Atlanta's Georgia Dome hosted Super Bowl XXVIII in 1994 and Super Bowl XXXIV in 2000. The dome has hosted the NCAA Final Four Men's Basketball National Championship in 2002, 2007, and 2013.[124] It hosted WWE's WrestleMania XXVII in 2011, an event which set an attendance record of 71,617. The venue was also the site of the annual Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl post-season college football games. Since 2017, they have been held at the Mercedes-Benz Stadium along with the FIRST World Championships.

Professional baseball's Ty Cobb was the first player inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He was from Narrows, Georgia and was nicknamed the "Georgia Peach".[125]

The Mercedes-Benz Stadium hosted Super Bowl LIII in 2018 and the CFP National Championship in the same year, the SEC Championship Game in 2017, the MLS All-Star Game in 2018, the MLS Cup in 2018, and the record-setting friendly fixture between Mexico Men's National Football Team and Honduras Men's National Football Team.

Culture[edit]

The people of Georgia have been named 'Peaches' after the amount of peaches grown and distributed from Georgia.

Fine and performing arts[edit]

Georgia's major fine art museums include the High Museum of Art and the Michael C. Carlos Museum, both in Atlanta; the Georgia Museum of Art on the campus of the University of Georgia in Athens; Telfair Museum of Art and the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah; and the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta.[126]

The state theatre of Georgia is the Springer Opera House located in Columbus.

The Atlanta Opera brings opera to Georgia stages.[127] The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra is the most widely recognized orchestra and largest arts organization in the southeastern United States.[128]

There are a number of performing arts venues in the state, among the largest are the Fox Theatre, and the Alliance Theatre at the Woodruff Arts Center, both on Peachtree Street in Midtown Atlanta as well as the Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre, located in Northwest Atlanta.

Education[edit]

Georgia county and city public school systems are administered by school boards with members elected at the local level. As of 2013[update], all but 19 of 181 boards are elected from single-member districts. Residents and activist groups in Fayette County sued the board of commissioners and school board for maintaining an election system based on at-large voting, which tended to increase the power of the majority and effectively prevented minority participation on elected local boards for nearly 200 years.[129] A change to single-member districts has resulted in the African-American minority being able to elect representatives of its choice.

Georgia high schools (grades nine through twelve) are required to administer a standardized, multiple choice End of Course Test, or EOCT, in each of eight core subjects: algebra, geometry, U.S. history, economics, biology, physical science, ninth grade literature and composition, and American literature. The official purpose of the tests is to assess "specific content knowledge and skills". Although a minimum test score is not required for the student to receive credit in the course, completion of the test is mandatory. The EOCT score accounts for 15% of a student's grade in the course.[130] The Georgia Milestone evaluation is taken by public school students in the state.[131] In 2020, because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Georgia State BOE agreed to state superintendent Richard Woods' proposal to change the weight of the EOCT test to only count for 0.01% of the Student's course grade. This change is currently only in effect for the 2020–21 school year.[132]

Georgia has 85 public colleges, universities, and technical colleges in addition to more than 45 private institutes of higher learning. Among Georgia's public universities is the flagship research university, the University of Georgia, founded in 1785 as the country's oldest state-chartered university and the birthplace of the American system of public higher education.[133] The University System of Georgia is the presiding body over public post-secondary education in the state. The System includes 29 institutions of higher learning and is governed by the Georgia Board of Regents. Georgia's workforce of more than 6.3 million is constantly refreshed by the growing number of people who move there along with the 90,000 graduates from the universities, colleges and technical colleges across the state, including the highly ranked University of Georgia, Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia State University and Emory University.[134]

The HOPE Scholarship, funded by the state lottery, is available to all Georgia residents who have graduated from high school or earned a General Educational Development certificate. The student must maintain a 3.0 or higher grade point average and attend a public college or university in the state.[135]

The Georgia Historical Society, an independent educational and research institution, has a research center located in Savannah. The research center's library and archives hold the oldest collection of materials related to Georgia history in the nation.

Media[edit]

The Atlanta metropolitan area is the ninth largest media market in the United States as ranked by Nielsen Media Research. The state's other top markets are Savannah (95th largest), Augusta (115th largest), and Columbus (127th largest).[136]

There are 48 television broadcast stations in Georgia including TBS, TNT, TCM, Cartoon Network, CNN and Headline News, all founded by notable Georgia resident Ted Turner. The Weather Channel also has its headquarters in Atlanta.

By far, the largest daily newspaper in Georgia is the Atlanta Journal-Constitution with a daily readership of 195,592 and a Sunday readership of 397,925.[137][138] Other large dailies include The Augusta Chronicle, the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, The Telegraph (formerly The Macon Telegraph) and the Savannah Morning News.

WSB-AM in Atlanta was the first licensed radio station in the southeastern United States, signing on in 1922. Georgia Public Radio has been in service since 1984[139][140] and, with the exception of Atlanta, it broadcasts daily on several FM (and one AM) stations across the state. Georgia Public Radio reaches nearly all of Georgia (with the exception of the Atlanta area, which is served by WABE).

WSB-TV in Atlanta is the state's oldest television station, having begun operations in 1948. WSB the first television service in Georgia, and the South.[141]

Government[edit]

State government[edit]

As with all other U.S. states and the federal government, Georgia's government is based on the separation of legislative, executive, and judicial power.[142] Executive authority in the state rests with the governor, currently Brian Kemp (Republican). Both the Governor of Georgia and lieutenant governor are elected on separate ballots to four-year terms of office. Unlike the federal government, but like many other U.S. States, most of the executive officials who comprise the governor's cabinet are elected by the citizens of Georgia rather than appointed by the governor.

Legislative authority resides in the General Assembly, composed of the Senate and House of Representatives. The Lieutenant Governor presides over the Senate, while members of the House of Representatives select their own Speaker. The Georgia Constitution mandates a maximum of 56 senators, elected from single-member districts, and a minimum of 180 representatives, apportioned among representative districts (which sometimes results in more than one representative per district); there are currently 56 senators and 180 representatives. The term of office for senators and representatives is two years.[143] The laws enacted by the General Assembly are codified in the Official Code of Georgia Annotated.

State judicial authority rests with the state Supreme Court and Court of Appeals, which have statewide authority.[144] In addition, there are smaller courts which have more limited geographical jurisdiction, including Superior Courts, State Courts, Juvenile Courts, Magistrate Courts and Probate Courts. Justices of the Supreme Court and judges of the Court of Appeals are elected statewide by the citizens in non-partisan elections to six-year terms. Judges for the smaller courts are elected to four-year terms by the state's citizens who live within that court's jurisdiction.

Local government[edit]

Georgia consists of 159 counties, second only to Texas, with 254.[145] Georgia had 161 counties until the end of 1931, when Milton and Campbell were merged into the existing Fulton. Some counties have been named for prominent figures in both American and Georgian history, and many bear names with Native American origin. Counties in Georgia have their own elected legislative branch, usually called the Board of Commissioners, which usually also has executive authority in the county.[146] Several counties have a sole Commissioner form of government, with legislative and executive authority vested in a single person. Georgia is the only state with current Sole Commissioner counties. Georgia's Constitution provides all counties and cities with "home rule" authority. The county commissions have considerable power to pass legislation within their county, as a municipality would.

Georgia recognizes all local units of government as cities, so every incorporated town is legally a city. Georgia does not provide for townships or independent cities, though there have been bills proposed in the Legislature to provide for townships;[147] it does allow consolidated city-county governments by local referendum. All of Georgia's second-tier cities except Savannah have now formed consolidated city-county governments by referendum: Columbus (in 1970), Athens (1990), Augusta (1995), and Macon (2012). (Augusta and Athens have excluded one or more small, incorporated towns within their consolidated boundaries; Columbus and Macon eventually absorbed all smaller incorporated entities within their consolidated boundaries.) The small town of Cusseta adopted a consolidated city-county government after it merged with unincorporated Chattahoochee County in 2003. Three years later, in 2006, the town of Georgetown consolidated with the rest of Quitman County.

There is no true metropolitan government in Georgia, though the Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) and Georgia Regional Transportation Authority do provide some services, and the ARC must approve all major land development projects in the Atlanta metropolitan area. [citation needed]

Elections[edit]

Georgia voted Republican in six consecutive presidential elections from 1996 to 2016, a streak that was broken when the state went for Democratic candidate Joe Biden in 2020.[148]

Until 1964, Georgia's state government had the longest unbroken record of single-party dominance, by the Democratic Party, of any state in the Union. This record was established largely due to the disenfranchisement of most blacks and many poor whites by the state in its constitution and laws in the early 20th century. Some elements, such as requiring payment of poll taxes and passing literacy tests, prevented blacks from registering to vote; their exclusion from the political system lasted into the 1960s and reduced the Republican Party to a non-competitive status in the early 20th century.[149]

White Democrats regained power after Reconstruction due in part to the efforts of some using intimidation and violence, but this method came into disrepute.[150] In 1900, shortly before Georgia adopted a disfranchising constitutional amendment in 1908, blacks comprised 47% of the state's population.[151]

The whites dealt with this problem of potential political power by the 1908 amendment, which in practice disenfranchised blacks and poor whites, nearly half of the state population. It required that any male at least 21 years of age wanting to register to vote must also be of good character and able to pass a test on citizenship, be able to read and write provisions of the U.S. and Georgia constitutions, or own at least forty acres of land or $500 in property. Any Georgian who had fought in any war from the American Revolution through the Spanish–American War was exempted from these additional qualifications. More importantly, any Georgian descended from a veteran of any of these wars also was exempted. Because, by 1908, many white Georgia males were grandsons of veterans or owned the required property, the exemption and the property requirement basically allowed only well-to-do whites to vote. The qualifications of good character, citizenship knowledge, literacy (all determined subjectively by white registrars), and property ownership were used to disqualify most blacks and poor whites, preventing them from registering to vote. The voter rolls dropped dramatically.[150][152] In the early 20th century, Progressives promoted electoral reform and reducing the power of ward bosses to clean up politics. Their additional rules, such as the eight-box law, continued to effectively close out people who were illiterate.[19] White one-party rule was solidified.

For more than 130 years, from 1872 to 2003, Georgians nominated and elected only white Democratic governors, and white Democrats held the majority of seats in the General Assembly.[153] Most of the Democrats elected throughout these years were Southern Democrats, who were fiscally and socially conservative by national standards.[154][155] This voting pattern continued after the segregationist period.[156]

Legal segregation was ended by passage of federal legislation in the 1960s. According to the 1960 census, the proportion of Georgia's population that was African American was 28%; hundreds of thousands of blacks had left the state in the Great Migration to the North and Midwest. New white residents arrived through migration and immigration. Following support from the national Democratic Party for the civil rights movement and especially civil rights legislation of 1964 and 1965, most African-American voters, as well as other minority voters, have largely supported the Democratic Party in Georgia.[157]

In 2002, incumbent moderate Democratic Governor Roy Barnes was defeated by Republican Sonny Perdue, a state legislator and former Democrat. While Democrats retained control of the State House, they lost their majority in the Senate when four Democrats switched parties. They lost the House in the 2004 election. Republicans then controlled all three partisan elements of the state government.

Even before 2002, the state had become increasingly supportive of Republicans in Presidential elections. It has supported a Democrat for president only four times since 1960. In 1976 and 1980, native son Jimmy Carter carried the state; in 1992, the former Arkansas governor Bill Clinton narrowly won the state; and in 2020, Joe Biden narrowly carried the state. Generally, Republicans are strongest in the predominantly white suburban (especially the Atlanta suburbs) and rural portions of the state.[158] Many of these areas were represented by conservative Democrats in the state legislature well into the 21st century. One of the most conservative of these was U.S. Congressman Larry McDonald, former head of the John Birch Society, who died when the Soviet Union shot down KAL 007 near Sakhalin Island. Democratic candidates have tended to win a higher percentage of the vote in the areas where black voters are most numerous,[158] as well as in the cities among liberal urban populations (especially Atlanta and Athens), and the central and southwestern portion of the state.

The ascendancy of the Republican Party in Georgia and in the South in general resulted in Georgia U.S. House of Representatives member Newt Gingrich being elected as Speaker of the House following the election of a Republican majority in the House in 1994. Gingrich served as Speaker until 1999, when he resigned in the aftermath of the loss of House seats held by members of the GOP. Gingrich mounted an unsuccessful bid for president in the 2012 election, but withdrew after winning only the South Carolina and Georgia primaries.

In 2008, Democrat Jim Martin ran against incumbent Republican Senator Saxby Chambliss. Chambliss failed to acquire the necessary 50 percent of votes due to a Libertarian Party candidate receiving the remainder of votes. In the runoff election held on December 2, 2008, Chambliss became the second Georgia Republican to be reelected to the U.S. Senate.

In the 2018 elections, the governorship remained under control by a Republican (by 54,723 votes against a Democrat, Stacey Abrams), Republicans lost eight seats in the Georgia House of Representatives (winning 106), while Democrats gained ten (winning 74), Republicans lost two seats in the Georgia Senate (winning 35 seats), while Democrats gained two seats (winning 21), and five Democrat U.S. Representatives were elected with Republicans winning nine seats (one winning with just 419 votes over the Democratic challenger, and one seat being lost).[159][160][161]

In the three presidential elections up to and including 2016, the Republican candidate has won Georgia by approximately five to eight points over the Democratic nominee, at least once for each election being narrower than margins recorded in some states that have flipped within that timeframe, such as Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin. This trend led to the state narrowly electing Democrat Joe Biden for president in 2020, and it coming to be regarded as a swing state.[162][163]

In a 2020 study, Georgia was ranked as 49th on the "Cost of Voting Index" with only Texas ranking higher.[164] In 2022, Georgia swung substantially back to the right towards Republicans with incumbent Republican Governor Brian Kemp winning reelection by 7.5% over Democrat Stacey Abrams with a raw vote margin of over 300,000 votes in the 2022 Georgia gubernatorial election. The largest amount since the early 2000s, and every other Republican statewide getting elected by a 5–10% margin of victory.[citation needed]

Politics[edit]

During the 1960s and 1970s, Georgia made significant changes in civil rights and governance. As in many other states, its legislature had not reapportioned congressional districts according to population from 1931 to after the 1960 census. Problems of malapportionment in the state legislature, where rural districts had outsize power in relation to urban districts, such as Atlanta's, were corrected after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964). The court ruled that congressional districts had to be reapportioned to have essentially equal populations.

A related case, Reynolds v. Sims (1964), required state legislatures to end their use of geographical districts or counties in favor of "one man, one vote"; that is, districts based upon approximately equal populations, to be reviewed and changed as necessary after each census. These changes resulted in residents of Atlanta and other urban areas gaining political power in Georgia in proportion to their populations.[165] From the mid-1960s, the voting electorate increased after African Americans' rights to vote were enforced under civil rights law.

Economic growth through this period was dominated by Atlanta and its region. It was a bedrock of the emerging "New South". From the late 20th century, Atlanta attracted headquarters and relocated workers of national companies, becoming more diverse, liberal and cosmopolitan than many areas of the state.

In the 21st century, many conservative Democrats, including former U.S. Senator and governor Zell Miller, decided to support Republicans. The state's then-socially conservative bent resulted in wide support for measures such as restrictions on abortion. In 2004, a state constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriages was approved by 76% of voters.[166] However, after the United States Supreme Court issued its ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, all Georgia counties came into full compliance, recognizing the rights of same-sex couples to marry in the state.[167]

In presidential elections, Georgia voted solely Democratic in every election from 1900 to 1960. In 1964, it was one of only a handful of states to vote for Republican Barry Goldwater over Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1968, it did not vote for either of the two parties, but rather the American Independent Party and its nominee, Alabama Governor George Wallace. In 1972, the state returned to Republicans as part of a landslide victory for Richard Nixon. In 1976 and 1980, it voted for Democrat and former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter. The state returned to Republicans in 1984 and 1988, before going Democratic once again in 1992. For every election between that year and 2020, Georgia voted heavily Republican, in line with many of its neighbors in the Deep South. In 2020, it voted Democratic for the first time in 28 years, aiding Joe Biden in his defeat of incumbent Republican Donald Trump.

Prior to 2020, Republicans in state, federal and congressional races had seen decreasing margins of victory, and many election forecasts had ranked Georgia as a "toss-up" state, or with Biden as a very narrow favorite.[168] Concurrent with the 2020 presidential election were two elections for both of Georgia's United States Senate seats (one of which being a special election due to the resignation of Senator Johnny Isakson, and the other being regularly scheduled). After no candidate in either race received a majority of the vote, both went to January 5, 2021, run-offs, which Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock won. Ossoff is the state's first Jewish senator, and Warnock is the state's first Black senator. Biden's, Ossoff's, and Warnock's wins were attributed to the rapid diversification of the suburbs of Atlanta[169] and increased turnout of younger African American voters, particularly around the suburbs of Atlanta and in Savannah, Georgia.[170][171][172]

Parks and recreational activities[edit]

There are 48 state parks, 15 historic sites, and numerous wildlife preserves under supervision of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.[173] Other historic sites and parks are supervised by the National Park Service and include the Andersonville National Historic Site in Andersonville; Appalachian National Scenic Trail; Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area near Atlanta; Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park at Fort Oglethorpe; Cumberland Island National Seashore near St. Marys; Fort Frederica National Monument on St. Simons Island; Fort Pulaski National Monument in Savannah; Jimmy Carter National Historic Site near Plains; Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park near Kennesaw; Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta; Ocmulgee National Monument at Macon; Trail of Tears National Historic Trail; and the Okefenokee Swamp in Waycross, Georgia[174]

Outdoor recreational activities include hiking along the Appalachian Trail; Civil War Heritage Trails; rock climbing and whitewater kayaking.[175][176][177][178] Other outdoor activities include hunting and fishing.

Infrastructure[edit]

Transportation[edit]

Transportation in Georgia is overseen by the Georgia Department of Transportation, a part of the executive branch of the state government. Georgia's major Interstate Highways are I-20, I-75, I-85, and I-95. On March 18, 1998, the Georgia House of Representatives passed a resolution naming the portion of Interstate 75, which runs from the Chattahoochee River northward to the Tennessee state line the Larry McDonald Memorial Highway. Larry McDonald, a Democratic member of the House of Representatives, had been on Korean Air Lines Flight 007 when it was shot down by the Soviets on September 1, 1983.

Georgia's primary commercial airport is Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL), the world's busiest airport.[179] In addition to Hartsfield–Jackson, there are eight other airports serving major commercial traffic in Georgia. Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport is the second-busiest airport in the state as measured by passengers served, and is the only additional international airport. Other commercial airports (ranked in order of passengers served) are located in Augusta, Columbus, Albany, Macon, Brunswick, Valdosta, and Athens.[180]

The Georgia Ports Authority manages two deepwater seaports, at Savannah and Brunswick, and two river ports, at Bainbridge and Columbus. The Port of Savannah is a major U.S. seaport on the Atlantic coast.

The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) is the principal rapid transit system in the Atlanta metropolitan area. Formed in 1971 as strictly a bus system, MARTA operates a network of bus routes linked to a rapid transit system consisting of 48 miles (77 km) of rail track with 38 train stations. MARTA operates almost exclusively in Fulton and DeKalb counties, with bus service to two destinations in Cobb county and the Cumberland Transfer Center next to the Cumberland Mall, and a single rail station in Clayton County at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport. MARTA also operates a separate paratransit service for disabled customers. As of 2009[update], the average total daily ridership for the system (bus and rail) was 482,500 passengers.[181]

Health care[edit]

The state has 151 general hospitals, more than 15,000 doctors and almost 6,000 dentists.[182] The state is ranked forty-first in the percentage of residents who engage in regular exercise.[183]

Notable people[edit]

Jimmy Carter, from Plains, Georgia, was President of the United States from 1977 to 1981. Martin Luther King Jr. was born in Atlanta in 1929. He was a civil rights movement leader who protested for equal rights and against racial discrimination. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.[184] Blake R. Van Leer played an important role in the civil rights movement, Georgia's economy and was president of Georgia Tech.[185] Mordecai Sheftall, the highest ranking Jewish officer in the American Revolution, was born and lived his life in Georgia.[186] Naomi Chapman Woodruff, originally from Idaho, was responsible for developing a peanut breeding program in Georgia which lead to a harvest of nearly five times the typical amount.[187]

State symbols[edit]

- Amphibian: American green tree frog

- Bird: brown thrasher

- Crop: peanut

- Fish: largemouth bass

- Flower: Cherokee rose

- Fruit: peach

- Gem: quartz

- Insect: honey bee

- Mammal: white-tailed deer[188]

- Marine mammal: right whale

- Mineral: staurolite

- Nicknames:

- "Peach State"

- "Empire State of the South"[189]

- Reptile: gopher tortoise

- Song: "Georgia on My Mind"

- Tree: live oak

- Vegetable: Vidalia onion

- Reference: Georgia Symbols[190]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ Persons of Hispanic or Latino origin are not distinguished between total and partial ancestry.

References[edit]

- ^ "Georgia State Symbols :: Capitol Museum, Atlanta :: University of Georgia". Archived from the original on January 8, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "US Census Quickfacts, Population Estimates, July 1 2023". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2019 Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Georgia - Atlanta, Sherman's March & Martin Luther King Jr". The History Channel. December 21, 2022. Archived from the original on June 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "New Georgia Encyclopaedia". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Grem, Darren (January 20, 2004). "Henry W. Grady (1850–1889)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Coweta is the 41st fastest growing county in United States". The Times-Herald. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "United States Summary: 2010, Population and Housing Unit Counts, 2010 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. September 2012. pp. V–2, 1 & 41 (Tables 1 & 18). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ "Georgia Facts and Symbols—Georgia.gov". Archived from the original on May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Trustee Georgia, 1732–1752". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. July 27, 2009. Archived from the original on August 31, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "The Articles of Confederation: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. July 10, 2014. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ "Georgia Constitution". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ Remini, Robert (1998) [1977]. "The Creek War: Victory". Andrew Jackson: The Course of American Empire, 1767–1821. Vol. 1. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801859115.

- ^ Justice, George (2006) [June 6, 2017]. "Georgia Secession Convention of 1861". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities. Archived from the original on January 27, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Georgia General Assembly. "A Resolution". 11 LC 94 5133, House Resolution 989. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ ""Atlanta in the Civil Rights Movement", Atlanta Regional Council for Higher Education". Atlantahighered.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Crowe, Charles (January 1, 1968). "Racial Violence and Social Reform-Origins of the Atlanta Riot of 1906". The Journal of Negro History. 53 (3): 234–256. doi:10.2307/2716218. JSTOR 2716218. S2CID 150050901.

- ^ a b Historical Census Browser, 1900 Federal Census, University of Virginia Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 15, 2008

- ^ "Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, "Supplement: Lynching by County" 2nd edition, Montgomery, Alabama: Equal Justice Initiative, 2015" (PDF). Eji.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Grantl, Jake (November 14, 2019). "Rearview Revisited: Segregation and the Sugar Bowl". Georgia Tech. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ "For 50 Years, Nuclear Bomb Lost in Watery Grave". NPR. February 3, 2008. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ a b "Atlanta's Hartsfield–Jackson International: Facts About The World's Busiest Airport". amaconferencecentersspeak.com. American Management Association. March 30, 2018. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ a b Morton, William J. (April 4, 2016). "How Georgia got its northern boundary – and why we can't get water from the Tennessee River". Saporta Report. Atlanta. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ Ulrich Bonnell Phillips (1902). Georgia and state rights: a study of the political history of Georgia from the Revolution to the Civil War. Annual Report of American Historical Association for the 57th US Congress, 1901. p. 30. Archived from the original on February 6, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ "In drought, water found: next door". Los Angeles Times. February 10, 2008. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Georgia Overview". uga.edu. Athens, Georgia: Natural Resources Spatial Analysis Lab, University of Georgia. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ Tegus – Georgia Invasive Species Task Force [full citation needed]

- ^ Monthly Averages for Macon, GA Archived April 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine The Weather Channel.

- ^ Monthly Averages for Clayton, GA Archived April 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine The Weather Channel.

- ^ "Georgia USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ Each state's high temperature record Archived July 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine USA Today, last updated August 2004.

- ^ "Each state's low temperature record". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 27, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2017. USA Today, last updated August 2006