Front porch campaign

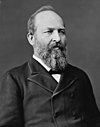

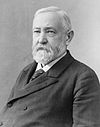

A front porch campaign is a low-key electoral campaign used in American politics in which the candidate remains close to or at home to make speeches to supporters who come to visit.[1] The candidate largely does not travel around or otherwise actively campaign.[2] The successful presidential campaigns of James A. Garfield in 1880, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, and William McKinley in 1896 are perhaps the best-known front porch campaigns.

McKinley's opposing candidate, William Jennings Bryan, gave over 600 speeches and traveled many miles all over the United States to campaign, but McKinley outdid this by spending about twice as much money campaigning.[3] While McKinley was at his Canton, Ohio, home conducting his "front-porch campaign", Mark Hanna was out raising millions to help with the campaign.

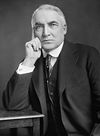

Another president known for his front porch campaign was Warren G. Harding during the presidential election of 1920.

In 2020, Joe Biden's presidential campaign shifted to a front-porch style during the summer, sometimes referred to as his basement campaign.[4] He used videoconferencing technology to fundraise and speak to supporters and the media from his home in Delaware during the COVID-19 pandemic given the imposition of stay-at-home orders[5] and his belief that rallies were impractical and a public health hazard.[6][7]

McKinley campaign[edit]

Throughout the course of the 1896 United States presidential election, William McKinley spoke to more than 700,000 supporters in front of his house in Canton.[8] These speeches started as organized meetings between McKinley and delegations from all over the nation. Although it was expensive for the campaign to bring these delegations, all in all, this idea became a good strategy because of the publicity it generated. In addition, due to the fact that McKinley's campaign chose those who would travel as part of the delegation, it was possible to make those who spoke portray McKinley positively.[9]

McKinley's front-porch campaign was a big contrast to William Jennings Bryan's unprecedented whistle-stop train tour throughout the United States. A 2022 study used these different campaigning strategies to assess the impact of campaign visits. The study found that "campaign visits by Bryan increased his vote share by about one percentage point on average."[3]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Dolan, Michael (September 15, 2016). "Porch Politics: Candidates Stayed Home to Campaign". HistoryNet.com. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ "Front-Porch Campaign." Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2012.

- ^ a b Buggle, Johannes C; Vlachos, Stephanos (2022). "Populist Persuasion in Electoral Campaigns: Evidence from Bryan's Unique Whistle-Stop Tour". The Economic Journal. 133 (649): 493–515. doi:10.1093/ej/ueac056. ISSN 0013-0133.

- ^ Hounshell, Blake (June 28, 2022). "Fetterman 2022: The Steampunk Version of Biden in His Basement". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Garrison, Joey. "Biden in the basement: Can campaigning from home work as Trump starts to travel?". USA Today.

- ^ "Joe Biden takes his campaign to the digital front porch as coronavirus throws up new obstacles for Democrats". The Globe and Mail. March 25, 2020.

- ^ Sha fer, Ronald G. "Biden campaigns from his basement. Harding ran for president from his porch". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Marker #17-76 William McKinley." Remarkable Ohio. The Ohio Historical Society, 2003. Web. 14 Dec. 2012.

- ^ "#25: William McKinley: The Front Porch Campaign. N.p." presidentsbythebook.blogspot.com. February 26, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

External links[edit]

- A Front-Porch Campaign for Citizen Dole. (May 22, 1996)

- Front-porch campaign: You and the candidate – and 30 cameras. (July 19, 2004)

- Kerry announces Front Porch offensive. (September 2, 2004)

- Back-porch politics in 5th District race. (July 16, 2007)