Frank Buck (animal collector)

Frank Buck | |

|---|---|

Buck in a signed photograph from his souvenir booklet for the 1939 New York World's Fair | |

| Born | Frank Howard Buck March 17, 1884 Gainesville, Texas, United States |

| Died | March 25, 1950 (aged 66) Houston, Texas, United States |

| Occupations | |

| Years active | 1911–1949 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

Frank Howard Buck (March 17, 1884 – March 25, 1950) was an American hunter, animal collector, and author, as well as a film actor, director, and producer. Beginning in the 1910s he made many expeditions into Asia for the purpose of hunting and collecting exotic animals, bringing over 100,000 live specimens back to the United States and elsewhere for zoos and circuses and earning a reputation as an adventurer. He co-authored seven books chronicling or based on his expeditions, beginning with 1930's Bring 'Em Back Alive, which became a bestseller.

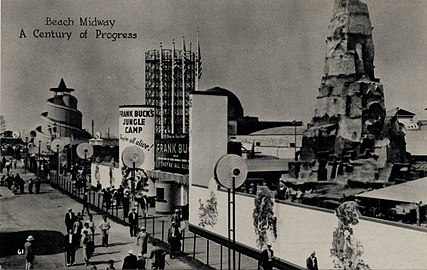

Between 1932 and 1943 he starred in seven adventure films based on his exploits, most of which featured staged "fights to the death" with various wild beasts. He was also briefly a director of the San Diego Zoo, displayed wild animals at the 1933–34 Century of Progress exhibition and 1939 New York World's Fair, toured with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, and co-authored an autobiography, 1941's All in a Lifetime. The Frank Buck Zoo in Buck's hometown of Gainesville, Texas, is named after him.

Animal collecting[edit]

According to Buck, in 1911 Buck won $3,500 in a poker game and decided to go abroad for the first time, traveling to Brazil without his wife.[1] According to a 1957 article about Buck's life, "For years he avoided telling about the poker game that staked him to his first venture in South America, instead claiming he had skimped and saved as an assistant taxidermist in a museum."[2] Bringing back exotic birds to New York, he was surprised by the profits he was able to obtain from their sale. He then traveled to Singapore, beginning a string of animal collecting expeditions to various parts of Asia. Leading treks into the jungles, Buck learned to build traps and snares to safely catch animals so he could sell them to zoos and circuses worldwide.[3] After an expedition, he would usually accompany his catches on board ship, helping to ensure they survived the transport to the United States.[3]

According to Ansel W. Robison, he both trained and funded the man whom The Rotarian magazine in 1972 called "a sideshow impresario and writer". Robinson, a pet store owner from the third generation of a family of San Francisco animal merchants, recalled from over a distance of some 50 years "the day Buck barked frantically over the telephone, 'Come quick, Ansel, the panther escaped when we were unloading it!' Robison hurried to the docks and together they inched the snarling, frightened cat into an awaiting cage."[4]

According to Robison, one day in 1915, Buck visited Robison's shop with an eye to purchasing Lady Gould finches (Chloebia gouldiae)[5] from a shipment that Robison had received from Australia.[6] Robison vividly recalled his first sight of Buck: "He was a slick-looking young fellow. All dressed up. Chamois gloves and spats. A regular fashion plate, and handsome and likable, too."[6][5] Buck was looking for pets "to keep in his hotel room".[7] Otherwise, at that time, "there was nothing to link him to animals...except a modest taste for finches."[6]

Buck, who had formerly been a Chicago newspaperman, worked in publicity for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Hired by Frank Burt, the Director of Concessions and Admissions,[8] Buck was there to drum up business for "the Zone" of the world's fair, which was the amusement-park-style "midway of that time".[6][9][10][7] According to the San Francisco Examiner in 1968, Robison initially "gave Buck ideas on the use of tropical birds for added interest at the exposition."[9] Buck began to visit frequently to talk to Ansel Robison and look at the animals until he was virtually "haunting the place".[6]

In late summer 1915 an "enormous orangutan" came from Java on a Russian tramp steamer otherwise loaded with sugar. Robison bought the steamer's animal cargo and rapidly sold the constrictor snake to a circus, but could not seem to find a buyer for the orangutan. Buck told him that at the Exposition Zone there was a "fast-talking carnival man named Don Carlos, whose concession was doing badly." Apparently Don Carlos[a] "had no money", but Buck suggested Robison let Don Carlos use the orangutan on a percentage basis until the end of the exposition "in a few weeks". According to Robison, the orangutan "was a sensation. Within two weeks Carlos brought in $750 as full payment for it, plus $500 as the pet shop's percentage of the receipts."[6]

Meanwhile, Robison had an order from the United States Department of Health[7] for 500 rhesus monkeys from India[5] at $20 each.[6] According to the Saturday Evening Post in 1953, "World War I was on and the monkeys were vitally needed for trench-gas experiments. But Ansel Robison could not seem to get any action out of his agents in India. But the order had to be filled; it was a patriotic necessity. Ansel began making preparations to go to India."[6]

After the close of the fair, Buck "announced he was taking a publicity job with a steamship company"[6] or was "going to the Orient as correspondent for a magazine,"[10] heading out shortly for Calcutta.[5] Robison commissioned Buck "to keep his eyes open for monkeys". Buck was initially reluctant, stating even if he were able to find so many rhesus monkeys, he had no money to buy or ship them. Robison told Buck, "I'll worry about the money."[6] Six weeks later Robison received a cablegram[6] from Buck in India that he had the monkeys, as well as two Bengal tigers, snakes, rare pheasants and some other birds. Buck added, "Send money."[7]

According to Robison: "He didn't know a damn thing about animals...[but] Frank did help, sending monkeys to me for government research...After that I financed all of Frank's trips for 10 years."[10] Per the Evening Post, "Robison put Buck back on the next steamer leaving for the Far East. With World War I on and the European markets closed, zoos, circuses, and dealers everywhere were looking to the Robison firm for supply."[6]

In his life story, coauthored by Ferrin Fraser, All In a Lifetime (1941), Buck claims his first Asian animal collecting trip was in "late 1912 and early 1913."[8] He states that from this first shipment he sold tigers and birds to Dr. Hornaday, leopards and pythons to Foley & Burke Carnival Company, and "the remaining birds to Robinson [sic] Bird Store and other dealers" for a net profit of $6,000, and three weeks later went back to Singapore.[8] He also states that after the close of the San Francisco world's fair he went to work as Director of Publicity and Promotion for Mack Sennett Studio for seven months but "it was the sunrises over the Malayan jungle that I missed...I headed back for Singapore, headed for everything the jungle and life could do for me."[8] According to Buck he was then involved in animal collecting for the next 16 years.[8]

Animal traders of Asia mentioned in Buck's autobiography include Yu Kee, "a Straits-born Chinese who had a godown...in a little alley way off Cross Street" in Singapore, and Husad Hassan's bird bazaar in Moore Street, the "bazaar of Minas, a Portuguese-Hindu half-caste, on Parsee Church Street," and Atool Accoli. Buck describes Acooli as the "least dishonest and undependable among as unreliable, cheating, and lying a group of traders as I ever contacted, before or since... Atool Acooli was the father of the present Acooli brothers, the best bird merchants in India."[8]

According to Robison, Buck traveled on Robison-financed animal collecting trips until 1925.[6][5][7] The Buck-to-Robison pipeline provided "elephants to circuses, llamas for the private zoo of Borax Smith, increased the private collection of William Randolph Hearst, provided animals for Wrigley's bird park on Catalina, Fleischhaker Zoo in San Francisco, and Cecil B. DeMille's movie The King of Kings."[5] Buck appears to mention Robison but once in his autobiography, and misspells the name.[8]

Perhaps simultaneously, but at least from 1917[13] to 1920,[14] Buck worked as a representative of Osaka Shosen Kaisha, a Japanese-owned steamship company. His work was under the editorship of M. Franklin Kline.[15] According to two passport applications in the archives of the U.S. Department of State, Buck was employed as a traveling agent for Osaka Shosen Kaisha's Official Guide for Shippers and Travelers to the Principal Ports of the World,[16][17] for the purpose of editorial research and "securing advertisements for the publication" on a commission basis.[14] Buck was assigned to visit Japan, China, Hong Kong, Straits Settlements, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), India, Java, Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, and British Possessions.[14] Buck does not mention his work traveling to the great ports of Asia for a Japanese steamship company in his 1941 autobiography, perhaps due to the Pacific War.[8]

According to the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, in 1923, Buck said he had made 14 animal collecting trips to Asia over the past seven years.[18] Buck reported satisfaction and acceptable profits if 70 percent of the birds and 80 percent of the animals survived the sea journey from Asia.[18] According to the Free Press reporter:

He made Singapore his headquarters, purchasing animals and birds as they arrived in the boats from Java, the Celebes, Borneo, Sumatra and the F.M.S. Gradually the collection grows as one by one the animals arrive and are taken up to the compound off the Orchard Road, to await the arrival of many more specimens, the result of a personal visit to India, Burma, and elsewhere, when all are placed aboard a ship at Singapore and taken to America.[18]

According to Robison, after WWI, German animal traders re-entered the market and operated more cheaply than Americans, and by 1925, the revised seaman's laws[b] made it "prohibitively expensive" to transport animals on American ships. Robison largely ended his import business, and the Robison-Buck connection was severed in 1925.[6]

According to one analysis, Buck's sensitivity to beauty has been illustrated by "Buck also did not find it necessary to make 'macho' choices when he divulged his favorite animal list...the fairy-bluebird—with its electric blue and coal black plumage—of the Malaysian Islands was irresistible to him. Very rare, the bird is shy and lives in the deepest jungles, but has the loveliest song."[2] In an interesting coincidence, ornithologist Edward H. Lewis, the founding director of the Catalina Bird Park (and thus someone Buck knew and to whom he had sold birds), also thought the fairy-bluebird of Asia was the most beautiful of birds.[20]

As the Oakland Tribune put it, Buck went on to fame as the "dashing, dauntless, devil-may-care hero of the big game world".[5] By the 1940s, Frank Buck claimed to have captured 49 elephants, 60 tigers, 63 leopards, 20 hyenas, 52 orangutans, 100 gibbons, 20 tapirs, 120 Asiatic antelope and deer, 9 pigmy water buffalo, a pair of gaurs, 5 babirusa, 18 African antelope, 40 wild goats and sheep, 11 camels, 2 giraffes, 40 kangaroos and wallabies, 5 Indian rhinoceros, 60 bears, 90 pythons, 10 king cobras, 25 giant monitor lizards, 15 crocodiles, more than 500 different species of other mammals, and more than 100,000 wild birds. Sultan Ibrahim of Johor was a good friend of Buck's and frequently assisted him in his animal collecting endeavors.[21]

In 1946, after the end of WWII, Buck told The New Yorker he intended to return to animal collecting in Singapore, saying, "You dig the same old-fashioned pits and use the same old-fashioned knives and come back with the same old-fashioned tigers."[3][22] It is unclear if Buck ever went animal collecting abroad again between the end of World War II and his death in 1950.[2]

San Diego Zoo directorship[edit]

In 1923 Buck was hired as the first full-time director of the San Diego Zoo, but his tenure there was brief and tumultuous.[23]

The zoo was still in its early years, having begun as an assortment of animal displays remaining from the 1915–16 Panama–California Exposition held in Balboa Park.[24] It had been granted a permanent site in 1921 (an area of about 140 acres in the park's northwestern quadrant) and most of its initial exhibits had been built over the following year, with a "grand opening" of the new grounds held on January 1, 1923.[25] The zoo was founded by the Zoological Society of San Diego and managed by its board of directors, with founding board member Frank Stephens having served as the part-time managing director without pay since its beginning.[26][27]

Most of the planning and development was being overseen by Society founder and president Dr. Harry M. Wegeforth, who was the driving force behind the zoo's creation.[23][28][29][30] A strong-willed, hands-on president, Wegeforth walked the zoo grounds daily and had a singular vision for its future, with little room for opposing viewpoints.[23][29][30] Philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps, who had made several significant donations to the zoo, suggested that it needed a full-time director and volunteered to pay such a person's salary for three years if Wegeforth could find someone suitable for the job.[26][31] Wegeforth visited Dr. William Temple Hornaday, director of the New York Zoological Park, hoping Hornaday would recommend someone, but received a cold response.[26][31] He was surprised, then, to receive a call from Buck saying he had been referred by Hornaday as a possible candidate for the position.[26][31]

Buck was headed to India at the time, and struck an agreement with the Zoological Society's board for him to collect some animals for the zoo and then come to San Diego to become its director.[26][31] It was strongly hoped that his acquisitions would include elephants, an animal the Society, and particularly Wegeforth, had been attempting to add to the zoo's collection for some time.[32] Buck found two female Asian elephants in Calcutta named "Empress" and "Queenie" that were trained to work, and bought them for the zoo.[32] When the elephants arrived in San Diego after a long journey by boat and freight train, Wegeforth and superintendent Harry Edwards rode them through the city streets to the zoo.[32][33]

Buck soon arrived with the rest of the promised animals, including two orangutans, a leopard cub, two gray langurs, two kangaroos, three flamingos, two lion-tailed macaques, two sarus cranes, four demoiselle cranes, assorted geese, and a 23-foot reticulated python named Diablo that became famous when it would not eat and had to be regularly force-fed by a team of men using a feeding tube attached to a meat grinder, a spectacle that attracted thousands of onlookers and became a paid event until the snake's death in 1928.[34][35][36]

Buck began his directorship of the San Diego Zoo on June 13, 1923, signed to a three-year contract at an annual salary of $4,000 (equivalent to about $55,500 in 2015).[23][29] He was enthusiastic at first, telling reporters "We have the best zoo west of Chicago, and we are going to make it even bigger and better."[23] However, Buck, a self-made, solitary, rugged, and independent-minded individual, soon clashed with the board of directors, particularly Wegeforth.[23][29][30]

Members of the board complained that Buck was unwilling to consult with them on everyday policy and frequently defied their directives; he constructed new cassowary cages of his own design in direct defiance of their orders, they said, and had bragged to board member William Raymenton about "putting one over on the board by constructing the cage without their knowledge", boasting that he would continue to build whatever cages he considered proper "with or without the consent of the board".[23][29] He had also been instructed to build an enclosure for a zebu that had been allowed to wander the zoo grounds, but apparently ignored the directive.[29] According to Wegeforth, Buck made business deals with other zoos and animal collectors that were mismanaged or undocumented, and ordered expensive custom nameplates for the zoo's animals and exhibits which had to be returned when it was found that Buck had misspelled half of the names.[23][29]

Prior to receiving Empress and Queenie, Wegeforth had struck a deal with John Ringling to acquire elephants from the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus; when Ringling telegraphed that the circus was returning to San Diego and he was bringing the promised elephants, Wegeforth recorded that "without consulting me, [Buck] wired back declining the elephants and asking for other animals instead! I was dumbfounded when I learned about this on the circus' arrival—hardly adequate thanks for Mr. Ringling's trouble in transporting them across the continent for us. Of course, they did not carry a side line of animals around with them like spare tires but they did give us a tiger, a zebra, and a camel."[33]

The final straw involved an incident with Empress and Queenie: Buck believed that their hides appeared dry and cracked and would benefit from "oiling", an old practice in zoos and circuses in which elephants were covered in neatsfoot oil to soften and condition their skin, the oil being washed off after a few days.[23][29][37] Wegeforth, a physician, took a strong interest in veterinary medicine and personally monitored the health of the animals, and had learned that oiling could cause pneumonia or Bright's disease in elephants.[23][29][38] He therefore ordered Buck never to oil Empress and Queenie.[23][29]

Buck oiled them anyway, and according to Wegeforth "they became very piteous-looking creatures, their trunks grew flaccid and seemed about a foot longer than usual, and their abdomens almost touched the ground. I was afraid they were doomed. We mixed Epsom salts with bran and, by using alfalfa meal, at last caused their bowels to move and relieved them of much of the edema. Some time passed before they were able to use their trunks but eventually they were as well as ever."[23][29][38] Returning from a trip to San Francisco a few months later, Wegeforth found that Buck had oiled the elephants a second time.[29][38] They recovered again, but Buck was immediately fired and left San Diego after only three months as director of the zoo, the board of directors charging that he "couldn't be trusted".[29][38]

Buck promptly sued the board of directors for breach of contract, saying he had given up his lucrative animal collecting business to work in San Diego and had suffered damage to his reputation.[23][29][38] He sought $12,500 in salary which he would have received in his three-year contract, as well as $10,000 in damages (a total equivalent to about $312,285 in 2015).[39] He sued Wegeforth personally, and when the matter went to court in February 1924 Buck accused Wegeforth of interfering with "practically everything" related to his job, and of conspiring with the board to "belittle and disparage" his efforts as director.[23][29][38]

Wegeforth accused Buck of incompetence and testified that "the whole character of the man was insubordination."[23][29] Buck also claimed that Wegeforth had killed a sick tiger by dosing the animal with calomel, and that the doctor's experiments in force-feeding snakes with a sausage stuffer had resulted in the deaths of 150 of the reptiles.[23][29] Wegeforth had in fact administered calomel tablets to a tiger suffering an intestinal ailment in August 1923, and in his memoirs described experimenting with methods of force-feeding Diablo the python before coming up with the idea to tube-feed the snake using a sausage stuffer.[36][40][41]

Board member Thomas Faulconer and other witnesses, however, suggested that the sick tiger had died after a suspicious blow to the head, and flatly denied the snake-killing accusation.[23][29] Wegeforth claimed that Buck himself had mistreated the reptiles, saying that he had "stuffed down, by the most inhuman way of feeding, snake meat down the throat of a boa constrictor instead of using a more modern method of stomach tube or feeding the meat through a tube."[23] On February 20, 1924, superior court judge Charles Andrews ruled against Buck and ordered him to pay court costs of $24 (equivalent to about $333 in 2015).[23]

In his 1941 autobiography All in a Lifetime, Buck did not mention his clashes with the Zoological Society board, his firing, or the subsequent lawsuit.[23] He did, however, claim that "while acting as temporary director of the San Diego Zoo", he had invented a method of force-feeding snakes, the means "by which captive pythons are mainly fed today".[23] He made one subsequent contribution to the zoo, though indirectly: Having returned to his animal-collecting career, in 1925 he brought a shipment of animals to San Diego including a salmon-crested cockatoo named King Tut from the Maluku Islands.[42][43][44][45] The bird was sold to a La Mesa, California, couple who shared it with the zoo.[46][47][48]

King Tut went appeared in several films, television shows, and theater productions, and was the "official greeter" of the zoo for decades, sitting on a perch inside the entrance to squawk at guests[44][45][48][49] Following King Tut's death in 1990, a bronze statue of the cockatoo was placed in the location of its longtime perch and remains there today, its plaque indicating that the bird "was brought from Indonesia in 1925 by Frank Buck".[49][50]

Media and celebrity[edit]

By the end of the 1920s Buck claimed he was the world's leading supplier of wild animals.[51] The Wall Street Crash of 1929 left him penniless, but friends lent him $6,000 and he was soon doing profitable work again.

When Chicago radio and newsreel personality Floyd Gibbons suggested that Buck write about his animal collecting adventures, he collaborated with journalist Edward Anthony to co-author Bring 'Em Back Alive (1930), which became a bestseller and earned him the nickname Frank "Bring 'Em Back Alive" Buck. He arranged for a film crew to accompany him on his next collecting expedition to Asia in order to create a film of the same title, which was released in 1932 and starred Buck as himself.[3] RKO Pictures created a triplet of financially lucrative films in the early 1930s that all dramatized "man versus ape" encounters: Ingagi (1930), Bring 'Em Back Alive and finally King Kong (1933).[52]

He was also the main feature of Bring 'Em Back Alive, an NBC radio program promoting the film which aired October 30 – December 18, 1932, and July 16 – November 16, 1934.[53] The follow-up book, Wild Cargo (1932), again co-authored with Anthony, also became a bestseller and was adapted into a 1934 film of the same title in which Buck once again portrayed himself and also served as producer. Armand Denis, the director of Wild Cargo and later a renowned wildlife documentarian, wrote about the filming in his 1963 autobiography. He recalled being bewildered by Buck's disinterest in "equipment" for the shoot, Buck's disdain for naturalistic observation of wildlife, and by Buck's suggestion that an orangutan fight a tiger on film. Denis described the Indian rhino that was shipped to Buck's "jungle camp" in Johor Bahru (nowhere near the jungle) for the production, and how he calmly wrestled with the corpse of "the large placid old tiger specially hired from a local animal dealer" when it drowned in its pit during filming.[54][55] During this time Buck was represented by George T. Bye, a New York literary agent.

Buck's third book, Fang and Claw (1935), was co-authored with Ferrin Fraser; for the film adaptation, Buck directed and once again starred. Tim Thompson in the Jungle (1935), also co-authored with Fraser, was a work of fiction but was based on Buck's experiences.

While these books and films made Buck world-famous, he later remarked that he was prouder of his 1936 elementary school reader, On Jungle Trails, saying "Wherever I go, children mention this book to me and tell me how much they learned about animals and the jungle from it."[56] Buck next starred as Jack Hardy in 1937's Jungle Menace (1937), a 15-part serial film that was the only picture in which he did not play himself. Prior to and during the making of Jungle Menace, Buck was represented by Hollywood literary agent H.N. Swanson.

During 1938, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus made Buck a lucrative offer to tour as their main attraction, and to enter the show astride an elephant. He refused to join the American Federation of Actors, stating that he was "a scientist, not an actor". Though there was a threat of a strike if he did not join the union, he maintained that it would compromise his principles, saying "Don't get me wrong. I'm with the working man. I worked like a dog once myself. And my heart is with the fellow who works. But I don't want some union delegate telling me when to get on and off an elephant."[57] Eventually the union gave Buck a special dispensation to introduce Gargantua the gorilla without registering as an actor. In conjunction with his 1939 World's Fair exhibit, Buck released a sixth book, Animals Are Like That, coauthored with Carol Weld.[58]

World War II temporarily halted Buck's expeditions to Asia, but his popularity kept him busy on the lecture circuit and making guest appearances on radio.[3] During the war years he continued to publish books and star in films: In 1941 he published an autobiography, All in a Lifetime, co-authored by Fraser, and narrated Jungle Cavalcade, a compilation of footage from his first three films. He also appeared in Jacaré (1942) and starred in Tiger Fangs (1943). His eighth and final book, Jungle Animals, again co-authored by Fraser, was published in 1945 and was intended for schoolchildren grades five to eight.[59]

Buck's final film role was an appearance as himself in the 1949 Abbott and Costello comedy Africa Screams.[3] His last recorded performance was Tiger, a 1950 children's record adapting two stories from Bring 'Em Back Alive.[3]

Buck had bylines in the Saturday Evening Post,[60] Collier's,[60] and the Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine.[61]

His endorsement deals included tires, toys, clothing,[62] Pepsodent,[63] Dodge automobiles,[64] Armour meats,[65] Stevens buckhorn rifles,[66] Camel cigarettes,[67] and Cream of Kentucky whiskey.[68]

Published works[edit]

- Bring 'Em Back Alive (1930), co-authored by Edward Anthony

- Wild Cargo (1932), co-authored by Edward Anthony

- Fang and Claw (1935), co-authored by Ferrin Fraser

- Tim Thompson in the Jungle (1935), co-authored by Ferrin Fraser

- On Jungle Trails (1936), co-authored by Ferrin Fraser

- Animals Are Like That (1939), co-authored by Carol Weld

- All in a Lifetime (1941), co-authored by Ferrin Fraser

- Jungle Animals (1945), co-authored by Ferrin Fraser

Filmography[edit]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | Bring 'Em Back Alive | Himself / narrator | Documentary / reenactment |

| 1934 | Wild Cargo | Himself | Documentary / reenactment actor, narrator, and producer |

| 1935 | Fang and Claw | Himself | Documentary / reenactment actor and director |

| 1937 | Jungle Menace | Frank Hardy | |

| 1941 | Jungle Cavalcade | Narrator / Himself | Documentary |

| 1942 | Jacaré | Himself | Documentary |

| 1943 | Tiger Fangs | Himself | |

| 1949 | Africa Screams | Himself |

Animal exhibits in Chicago, Queens and Long Island[edit]

Chicago: Buck furnished a wild animal exhibit, Frank Buck's Jungle Camp, for Chicago's Century of Progress exhibition in 1934. More than two million people visited Buck's reproduction of the camp he and his native assistants lived in while collecting animals in British Malaya.[3] The University of Chicago holds three souvenir booklets from the fair, including one for Frank Buck's Adventurer's Club for kids.[63] Another pamphlet promises the biggest orangutan in the world, the two biggest pythons in the world, "dragon lizards", Malayan honey bears, king cobras, 500 monkeys, 50 species of snakes, and "rare and beautiful birds from India."[69]

Long Island, New York: After the fair closed, he relocated the camp to a compound he created in Amityville, New York.[3] Buck's Long Island Zoo, located near Massapequa, seemingly existed from 1934[70] to the 1950's [71] According to the Massapequa Post, "Back then, the land where the mall now stands was thickly wooded, vacant and owned by a New York water company. The buildings that housed the animals were constructed with plain concrete blocks and wood-gabled roofs. There was a huge two story Tudor-style building close to the road" that housed reptiles and birds.[72]

According to Texas Highways magazine, "Buck had his staff grow mustaches and wear the same khaki outfit he did. Employees also carried autographed Frank Buck cards, so that when visitors came up and asked "Frank Buck" for an autograph, the employee just handed them a card."[73]

According to Hofstra University, which holds an archive of Frank Buck Zoo material, "For a twenty-five cent admissions fee, guests could view the animals, promotional movie posters, and large photographs of Buck's travels. Souvenirs and refreshments could be purchased at the camp. Buck's business partner and manager, T.A. Loveland, ran the zoo while Buck was busy traveling, writing, filming movies and giving lectures."[74]

Queens, New York: At decade's end, Buck brought his jungle camp to the 1939 New York World's Fair. "Frank Buck's Jungleland" displayed rare birds, reptiles, and wild animals, along with a five-year-old trained orangutan named Jiggs. In addition, Buck provided a trio of performing Asian elephants, an 80-foot "monkey mountain" with 600 monkeys, and camel rides.[3]

Jungle camp geography[edit]

Buck's exhibits at two World's Fairs and his Frank Buck's Jungleland zoo in Long Island, all opened in the 1930s, were designed around the conceit that the visitor was experiencing a replica of the "coolie camps" in the remote Oriental wilderness from which Buck had ventured forth, with traps and snares and "boys," to face down man-eating tigers and such.[75][76][77] (Sometimes in addition to exhibiting "his equipment used on jungle expeditions!"[69] Buck threw in a smoking volcano,[78][67] or black men costumed as "native Africans"[79] perhaps playing bongos.[80])

A brochure for the Pepsodent-sponsored Frank Buck Adventurer's Club, held in the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago Library includes a map with the locations of four camps with the note that the map is meant to help the reader "follow Frank Buck's adventures over his radio program." The map marks Singapore as Buck's "headquarters" with another camp in Johore, and a second near Siam (now Thailand), and a third in approximately Burma (now Myanmar) near the Bay of Bengal.[76]

According to Catherine Diamond, an English professor at Soochow University in Taipei, "In Singapore, his base for thirty years, Buck bought more animals from the shops of Chinese middlemen than he captured, but...Buck portrays himself as a man of action, both capturing animals and keeping them alive in his camp in Katong village outside of Singapore. Also as an established member of the international set that congregated at the Raffles Hotel bar, he personified the romance of colonial life."[81]

In All In a Lifetime, Buck states that he first rented an acre on Orchard Road in Tanglin for three years: "Here I built cages and shelter for what I had, arranged with DeBrunner to look after my compound while I was gone, with the help of the Malay boys who had been with me in the jungle." He later moved to four acres in Katong. In 1941, as World War II was well underway, Buck wrote, "I have maintained my Katong compound for two decades and am looking forward to returning to it in the near future."[8]

According to the Singapore Film Locations Archive, when filming Bring 'Em Back Alive, "Frank Buck...figured that he could pack similarly appealing jungle amusement in a film without plunging deep into the tropical forests...he probably never traveled beyond Sultan Ibrahim's estate in Johor to shoot his film...[the crew filmed] in menageries and rural spots in Singapore that appeared to resemble the remote Malayan and Sumatran jungles...In reality, there was no need to go hunting especially for the film shoot, as animal 'talents' were bountiful in Singapore's then-thriving menageries, wildlife wholesale centers and Mr. Basapa's Punggol Zoo."[82]

When Armand Denis was hired to direct Wild Cargo in 1934 an executive told him the location shoots would be "Ceylon for elephants, India for tigers, Malaya for cobras. If you can find a sabre-toothed tiger outside the Natural History Museum, you can go there as well."[54] When Denis later asked Buck what equipment he would be taking for the jungle, Buck replied, "I intend to stay at the Raffles Hotel in Singapore and I think they have most of the equipment I need there already." Denis stopped in Sri Lanka on his way east and filmed the Keddha elephant roundup and an elephant procession in Kandy, before continuing on to Singapore.[54]

Upon arrival, he found that Buck's camp "which I had imagined to be somewhere in the heart of the jungle, was a great disappointment...It was a hundred yards or so off the main road in Johor Bahru, just across the causeway from Singapore, on the edge of a rubber plantation. The camp was indeed conveniently near the Raffles Hotel, the race track, and other amenities of Singapore, but it was not even faintly reminiscent of the jungle. It consisted mainly of a few cages containing a variety of despondent-looking animals, and of a number of enclosures more or less ingeniously camouflaged and in which obviously the animals were to be placed for various scenes to be photographed. With a sinking heart I began to realize what was expected of me."[54]

Personal life[edit]

Buck was born in Gainesville, Texas in 1884[c] to Howard D. and Ada Sites Buck.[83] His father Howard D. Buck listed his occupation as "agricultural machinery dealer" in the 1880 census.[84] When he was five[60] or six,[73] "his family moved to Dallas, where his father, who was distantly related to the Studebaker family, went to work for their Dallas agency." Frank had an older brother Walter H. Buck,[84] a younger brother Harry O. Buck,[85] and a sister.[2]

He attended Dallas public schools,[83] and reportedly excelled at geography, at the cost of "utter failure on all the other subjects of that limited Dallas curriculum," and quit school after completing the seventh grade.[56][3] During childhood he began collecting birds and small animals, tried farming, and sold songs to vaudeville singers before getting a job as a cowboy.[3] As a teenager, he "lived at a ranch near San Angelo."[73] According to the Texas Handbook, "Buck left home at the age of 18 to take a job handling a trainload of cattle being sent to Chicago."[83]

In Chicago, while working as captain of bellhops at the Virginia Hotel, Buck met hotel resident Lillian West. A former actress and operetta singer, at the time they met she was one of the very few female drama critics in the country, and the only one working in Chicago, where she wrote for the Chicago Daily News under the pen name Amy Leslie.[86] In his autobiography, Buck described her as "a small woman, plump, with keenly intelligent eyes, the most beautifully white teeth I have ever seen, and a red, laughing mouth," adding that she was "always good-natured".[87]

Despite a 29-year age difference, Buck was 17, West 46, they married in 1901. On their marriage record, his age was listed as 24, hers was listed as 32.[88] They were listed as sharing a household on Crescent Street in Chicago in the 1910 census. His age was listed as 30, hers was listed as 35.[89] Buck's work was listed as "newspaper man" in the "advertising business".[89] Buck and West divorced in 1913.[90]

In 1924, Buck married Nina C. Boardman, a Chicago stenographer who later accompanied him on his travels.[90] Buck and Boardman divorced in 1927. When she later married a California packing company official, she told reporters, "As long as I live, I don't want to see any animals wilder or bigger than a kitten."[91]

Buck married Muriel Reilly in 1928, and the two had a daughter, Barbara. In 1937, he and Reilly bought their first home, at 5035 Louise Avenue in Encino, California, next door to the home of actor Charles Winninger.[92]

Buck spent his last years in his family home at 324 South Bishop Street in San Angelo, Texas, and died of lung cancer on March 25, 1950, in Houston, aged 66.[3][93]

Legacy[edit]

The artist Norman Rockwell painted a portrait of Frank Buck for a Schenley's Cream of Kentucky whiskey advertisement.[68] During World War II, a B-17 bomber crew named their plane the "Frank Buck" because it was going to bring them back alive.[94] Frank Duck Brings 'Em Back Alive is a 1946 animated short in which Donald Duck takes on the Frank Buck persona, and Goofy is a "wild man" of the jungle that he seeks to capture for the Ajax Circus.[95]

The Frank Buck exhibit at the New York World's Fair left a strong impression. In a 1985 New York Times review of a history of American world's fairs, William S. McFeely recalled "at the exhibit called Bring 'Em Back Alive, the great white hunter Frank Buck smiled down at me. I still remember the wonderful tiredness at the end of a day more satisfying than most since."[96] The main character of E.L. Doctorow's National Book Award-winning novel World's Fair (1985) also visited Jungleland, in the climatic final chapters of the story.[77]

Almost immediately we were off again, running down the Midway to Frank Buck's Jungleland. At last! It was a zoo technically, he had lots of different animals, but the railings were wood and the cages were portable, so it was more makeshift than a zoo, more in the nature of a camp. There were three different kinds of elephant, including a pygmy, and there was a black rhinoceros standing very still, as still as a structure, and who obviously understood nothing about where he was or why; there were a few sleeping tigers, none of them advertised as a man-eater; and tapirs, an okapi, and two sleek black panthers. You could ride on a camel's back, which we didn't do. On a miniature mountain, there lived, and screamed and swung and leaped and hung hundreds of rhesus monkeys. We watched them a long time. I explained Frank Buck to Meg. He went into the wilds of Malaya, usually, but also Africa, and trapped animals and brought them back here to zoos and circuses and sold them. I told her that was more humane to do than merely hunt them. In truth, I had worshiped Frank Buck, he lived the life I dreamed for myself, adventurous yet with ethical controls, he did not kill. But I had to confess to myself, though not to Meg, that I had now read his book twice and realized things about him I hadn't understood the first time. He complained a lot about the personalities of his animals. He got into scraps with them. Once an elephant picked him up and tossed him away. An orangutan bit him, and he nearly fell into a pit with a certified man-eating tiger. He called his animals devils, wretches, pitiful creatures, poor beasts and specimens. When one of them died on the ship to America, he felt sorry for it, but he seemed sorrier to lose the money the specimen would have brought. He called the Malays who worked for him in his camp "boys". Yet I could see now in the Malay village in Jungleland that these were men, in their loincloths and turbans, and they handled the animals in their care quite well. Frank Buck himself couldn't have been more impressive. They laughed among themselves and moved in and out of their bamboo shacks with no self-consciousness, barely attending to the patrons of Jungleland. I looked around for Frank Buck, knowing full well he wouldn't be here. I understood his legendary existence depended on his not being here, but I looked anyway. The truth was, I thought now, Frank Buck was a generally grumpy fellow, always cursing out his "boys" or jealously guarding his "specimens" or boasting how many he had sold where and for how much. He acted superior to the people who worked for him. He didn't get along with the authorities in the game preserves, nor with the ships' captains who took him on their freighters with his crated live cargo, nor with the animals themselves. I saw all that now, but I still wanted to be like him, and walk around with a pith helmet and a khaki shirt and a whip for keeping the poor devils in line. The Jungleland souvenir was a gold badge, with red and yellow printing. I pinned Meg's to her dress and mine to my shirt.

— E.L. Doctorow, World's Fair: A Novel, pp. 261–263

In 1953, Bring 'Em Back Alive was adapted into a comic book in the Classics Illustrated series (issue 104). The following year, the Gainesville Community Circus in Buck's hometown of Gainesville, Texas was renamed the Frank Buck Zoo in his honor.[97] Actor Bruce Boxleitner starred as Buck in the 1982–83 television series Bring 'Em Back Alive, which was partially based on Buck's books and adventures. In 2000, writer Steven Lehrer published Bring 'Em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck, an edited collection of Buck's stories.[98] In 2008 the Frank Buck Zoo opened the Frank Buck Exhibit, showcasing camp tools and media memorabilia that had once belonged to Buck and were donated by his daughter Barbara.[97]

Contemporary critical assessment[edit]

Daniel Bender, author of The Animal Game: Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo, argues that Buck was a fundamentally fraudulent character who told "many fibs...over the course of his long career," but that his manufactured persona was generally accepted in his time as exciting enough to warrant tolerance of the fiction masquerading as biography.[99] Catherine Diamond, in her paper comparing Buck to fellow animal collector and author Gerald Durrell, notes that Durrell remains widely read and even cherished, while Buck's work has languished with both critical audiences and the general public.[81] Diamond also observed that "The wild animal capture narrative belongs to a specific period—from the height of colonialism in the early twentieth century to the post-World War II aftermath—and reflects many American and European attitudes toward colonized peoples and territories."[81]

Steven Lehrer, a lifelong Frank Buck fan who edited and wrote the scholarly introduction to a compilation of Buck-and-coauthor-produced stories released in 2000, thought Buck deserved appreciation for publicizing the once-obscure wildlife of southern and eastern Asia. Nonetheless, Bender saw fit to extensively edit Buck's mangled Malay vocabulary.[59] According to Joanne Carol Joys and Randy Malamud in Reading Zoos argues that "accounts of Buck's adventures overstate his actual involvement in the capture of wild animals, and he served principally as a middleman between traders and American circuses and zoos" and that a comprehensive historic perspective on Buck's impact is obscured by his manufacture of his public persona as a "polymorphic phenomenon—trapper? animal aficionado? explorer? film star?"[2]

Joys writes, "Today, it is politically correct to cast Buck as a villain, a self-aggrandizing braggart who decimated the wilds to acquire animals for zoos and circuses, who opposed conservation measures, and racially demeaned the indigenous people of India and Southeast Asia, considering them as no more than his servants...Of course, the books, articles, and especially, the films, are filled with examples of animal combat. Since most of Buck's actual adventures occurred in the late teens and 1920s, and none of the supposed combats were either filmed or photographed, we have no way to know if they really occurred or were part of the lore surrounding the capture of wild animals in the region...Although most seem unlikely, they are not out of the realm of possibility...As for racist claims, Buck, if anything, seems condescending, but not racist. He was working in a colonial region, where white men were expected to maintain the upper hand. But Buck gave credit to the indigenous people for teaching him everything he knew about trapping and collecting wild animals, as well as repeatedly heaping praise on his assistants, and noting how beneath the skin all men are basically the same."[2]

Additional images[edit]

-

San Angelo, Texas, newspaper report, March 1921

-

Film crew for Bring 'Em Back Alive, Buck on far right

-

Frank Buck's Jungle Camp, 1934 Chicago

-

Poster for Czech release of Fang and Claw

-

Still from Jungle Menace (1937)

-

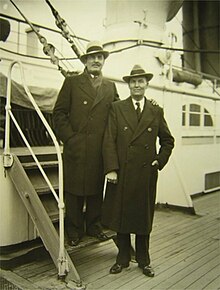

Buck, climbing out of a wicker howdah, with John Ringling North

-

1939 World's Fair souvenir

-

Tiger Fangs (1943) marketing material

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Per Billboard, after the closure of the Zone, the Don Carlos Dog and Monkey Hotel[11] with two "very fine chimps" was off to vaudeville with Sid Grauman.[12]

- ^ Unclear, but possibly Merchant Marine Act of 1920?[19]

- ^ U.S. passport applications filed in 1918 and 1920 record Buck's year of birth as 1881.[14]

References[edit]

- ^ Current Biography 1943, p. 86

- ^ a b c d e f Joys, Joanne Carol (May 2011). "Chapter III. Frank Buck". The Wild Things (Doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University). OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Van Dort, Paul M. "Frank Buck's Jungleland in the Amusement Zone". 1939 NY World's Fair. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009.

- ^ Harris, Audrey E. (September 1972). "Ansel Robison: Serving Animals and People". The Rotarian. Vol. 121, no. 3. p. 37. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hayes, Elinor (July 21, 1968). "How a World Famous Pet Shop Started". Oakland Tribune. p. 22. Archived from the original on December 17, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Morse, Ann (August 29, 1953). "They Sell People to Pets". Saturday Evening Post. Vol. 226, no. 9. Photography by Mason Weymouth. pp. 32–33, 42, 44. ISSN 0048-9239. Retrieved December 17, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e Wood, Dallas E. (September 24, 1942). "The Prowler". Redwood City Tribune. p. 8. Archived from the original on December 17, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Buck, Frank; Fraser, Ferrin L. (1941). All in a lifetime. New York: R. M. McBride & company. pp. 86 (first Asia trip), 93–94 (Yu Kee), 91 (Dahlam Ali), 101 (sales, profit), 108 (Orchard Road, Katong), 114–118 (SFPPIA, Sennett). Archived from the original on December 23, 2022. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Rhodes, George (May 6, 1968). "68 Years for Ansel Robison: Snakes, Apes, Dogs and People". San Francisco Examiner. p. 40. Archived from the original on December 17, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Morch, Albert (January 16, 1972). "Robison and his zoo story". San Francisco Examiner. p. 79 (cover of Sunday Women section). Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Trained dogs and monkeys running a dog and monkey hotel (LC-USZ62-77009 b&w film copy neg.)". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. 1915. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ Wilbur, Harry C. (December 18, 1915). "Get-Away Day Proved Zone's Biggest Some Future Activities of Some of the P.-P.I.E. Concessioners". The Billboard. Vol. 27, no. 51. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022 – via lantern.mediahist.org.

- ^ "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918", database with images, FamilySearch(https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K6J9-Z2N : 26 December 2021), Frank H Buck, 1917-1918.

- ^ a b c d "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QV5B-WRNL : 16 March 2018), Frank Howard Buck, 1920; citing Passport Application, California, United States, source certificate #68265, Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925, 1298, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

- ^ Greene, Sarah (June 24, 2020). "Passport Travels: Meyer Franklin Kline, globetrotting guidebook editor". The National Museum of American Diplomacy. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ "Official Shippers Guide to the Principal Ports of the World 16 冊一括". /mozubooks.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ "Osaka Shosen Kabushiki Kaisha". onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Zoologist in Asia". The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. February 10, 1923. p. 9. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Hutchins, John G. B. (June 1954). "The American Shipping Industry since 1914". Business History Review. 28 (2): 105–127. doi:10.2307/3111487. ISSN 0007-6805. JSTOR 3111487. S2CID 154041880. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ "The Vancouver Sun 05 Apr 1945, page 11". Newspapers.com. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Current Biography 1943, p. 84

- ^ Lanahan, Frances; Geoffrey T., Hellman (September 7, 1946). "The Talk of the Town". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Crawford, Richard (January 23, 2010). "Zoo Director Hired, Then Things Got Wild". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 7–12.

- ^ Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 27–36.

- ^ a b c d e Wegeforth and Morgan, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 11, 51.

- ^ Rutledge Stephenson, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b c d Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b c Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 52–55.

- ^ a b Wegeforth and Morgan, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Rutledge Stephenson, p. 65.

- ^ Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 69–74.

- ^ a b Wegeforth and Morgan, pp. 127–128.

- ^ The Illustrated American. Vol. VI. New York: The Illustrated American Publishing Company. 1891. p. 281. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Wegeforth and Morgan, p. 101.

- ^ Wegeforth and Morgan, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Rutledge Stephenson, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Wegeforth and Morgan, pp. 42–43.

- ^ "SDZG History Timeline". San Diego Zoo Global. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ Livingston, Bernard (2000) [First published 1974]. Zoo: Animals, People, Places (2000 ed.). Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse. pp. 100–102. ISBN 0-595-14623-6.

- ^ a b "King Tut". Zoonooz. San Diego: San Diego Zoo Global. November 1, 2015. p. 20.

- ^ a b Bruns, Bill (1983). A World of Animals: The San Diego Zoo and the Wild Animal Park. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 109. ISBN 0-8109-1601-0.

- ^ Ofield, Helen (March 8, 2008). "Animals Early Residents of Lemon Grove, Too". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ Grange, Lori (June 7, 1989). "King Tut Will Retire After 64 Years as Zoo Spokesfowl". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ a b Abrahamson, Alan (December 31, 1990). "King Tut, Zoo's Famous Longtime Greeter, Dies". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ a b "King Tut". sandiegozoo100.org. San Diego Zoo Global. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ Mancini, Julie Rach (2007). Why Does My Bird Do That? A Guide to Parrot Behavior (Second ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Publishing, Inc. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-470-03971-7.

- ^ "Frank Buck's Jungleland - 1939 York World's Fair - Amusement Zone". pmphoto.to. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ Erish, Andrew (January 8, 2006). "Reel History: Illegitimate Dad of Kong". The Los Angeles Times. pp. E6. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Denis, Armand (1963). "Chapter 5: Wild Cargo". On safari; the story of my life. E. P. Dutton & Co. Retrieved December 18, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Frank Buck and the Man Eater, archived from the original on December 19, 2022, retrieved December 19, 2022

- ^ a b Current Biography 1943, pp. 84–88

- ^ New York Post, May 5, 1938

- ^ Buck, Frank; Weld, Carol (1939). Animals are like that. New York: R.M. McBride and Co. Archived from the original on December 14, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b Lehrer, Steven (2006). Bring 'Em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck. Texas Tech University press. pp. x–xi. ISBN 0-89672-582-0. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Buck, Frank (1884–1950)". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. November 1, 1994. TID FBU05. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Buck, Frank (May 26, 1940). "Keep 'Em Alive". Los Angeles Times. This Week (magazine insert). p. J4, J20. ProQuest 165057189. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Taves, Brian (April 25, 2001). "Candidates for the National Film Registry: Fang and Claw & Tiger Fangs". National Film Preservation Board. Archived from the original on February 28, 2008.

- ^ a b "Guide to the Century of Progress International Exposition Publications 1933-1934". www.lib.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "Advertisement for Dodge 640 wih [sic] Melvin Purvis, Bing Crosby, William Harbridge, Warner Baxter, Mayor M.E. Trull, Carl Hubbell, Frank Buck, Roy Chapman Andrews Kitchen Appliances by Colliers editors: (1936) Magazine / Periodical". www.abebooks.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ "Vintage Ad: 1935 Armour Baked Ham W/ Frank Buck". tias.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ "Striking Vintage Brochure for "J. Stevens Arms Company" w/ Frank Buck on Cover *". eBay. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Bender, Daniel E. (collector) (1933). "It Takes Healthy Nerves for Frank Buck to Bring 'Em Back Alive! [advertisement]". University of Toronto Special Collections. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Jack (October 11, 2014). "MemoriesandMiscellany: Norman Rockwell Had a Head for Whiskey". MemoriesandMiscellany. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Century of Progress International Exposition Publications, Crerar Ms 226, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library, Box 11, Folder 8c, See: Frank Buck and his spectacular jungle camp, a wild cargo of rare animals, birds and reptiles, a Century of progress, 1934 View digitized document: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/ead/pdf/century0170.pdf Archived October 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "[The Frank Buck Hotel and Frank Buck's Animal Kingdom -- Opening Day]". nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ "Frank Buck's Zoo Historical Marker". hmdb.org. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ Meyer, John H. (September 30, 2009). "Frank Buck Zoo in Massapequa - Massapequa Post". Massapequa Post. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Moore, Natalie (March 1, 2010). "Call of the Wild". Texas Highways. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "Frank Buck Collection, 1935-1950 Special Collections Department/Long Island Studies Institute" (PDF). hofstra.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Pallone, Jillian (Spring 2018). "Frank Buck Bring 'Em Back Alive" (PDF). Long Island Studies Institute at Hofstra University. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Century of Progress International Exposition Publications, Crerar Ms 226, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library, Box 11, Folder 6, Official handbook for members of Frank Buck's adventurers club. Frank Buck's most thrilling adventure, circa 1934, Author: Pepsodent co., Chicago, Place: n.p., Collation: 22 p. illus., port. View digitized document: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/ead/pdf/century0165.pdf Archived December 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Doctorow, E. L. (1985). World's fair (1st ed.). New York: Random House. pp. 261–263. ISBN 0-394-52528-0. OCLC 12051431.

- ^ "Photo of an architectural drawing of Frank Buck's Animal Show exhibit at A Century of Progress International Exhibit". collections.carli.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Cleary, Kenneth (November 18, 2011). "African Americans and the World of Tomorrow". New-York Historical Society Museum & Library. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "Queens Public Library Digital". digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Diamond, Catherine (September 1, 2022). "Bring 'em Back Alive: Two Popular Narratives of Wildlife Capture". EurAmerica. 52 (3): 373–413.

- ^ Toh, Hun Ping (August 8, 2014). "Bring 'Em Back Alive (1932)". Singapore Film Locations Archive. Singapore Memory Project's irememberSG Fund. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Buck, Frank (1884–1950)". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. November 1, 1994. TID FBU05. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch(https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MFNM-LPL : 15 January 2022), A.j. Buck in household of H.d. Buck, Gainesville, Cooke, Texas, United States; citing enumeration district ED 111, sheet , NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm.

- ^ "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M2MS-QXW : accessed 10 December 2022), Howard D Buck, Dallas Ward 8, Dallas, Texas, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 60, sheet 19B, family 421, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 1544; FHL microfilm 1,375,557.

- ^ "Amy Leslie, Actress and Drama Critic: After Starring in Light Opera Was Writer for 40 Years". The New York Times. July 4, 1939

- ^ Frank Buck and Ferrin Fraser. All in a Lifetime. Robert M. McBride. New York: 1941, p. 52

- ^ "Michigan Marriages, 1822-1995", database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FC6D-JPX : 17 January 2020), Frank H. Buck, 1901.

- ^ a b "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch(https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MKZG-6B9 : accessed 10 December 2022), Frank H A Buck, Chicago, Cook, Illinois, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 1155, sheet , family , NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll ; FHL microfilm .

- ^ a b Lehrer, Steven (2006). Bring 'Em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck. Texas Tech University press. p. 248. ISBN 0-89672-582-0.

- ^ Cured of Fondness For Wild Animals. Montreal Gazette – Google News Archive – November 16, 1934

- ^ Variety, July 29, 1937

- ^ Bring 'Em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck, Texas Tech University Press, 2006, p. xviii. [1]

- ^ PacificWrecks.com. "Pacific Wrecks - B-17E "Frank Buck" Serial Number 41-2659". pacificwrecks.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Davison, Julian (2004). An Eastern Port and Other Stories. Topographica. p. 60. ISBN 978-981-05-0672-8. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- ^ McFeely, William S. (May 26, 1985). "Carnivals to Shape Our Culture". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Frank Buck Zoo: History". frankbuckzoo.com. Frank Buck Zoo. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Lehrer, Steven (2006). Bring 'Em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck. Texas Tech University press. pp. xi. ISBN 978-0-89672-582-9.

- ^ Bender, Daniel E. (2016). The animal game : searching for wildness at the American zoo. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-0-674-97275-9. OCLC 961185120. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Sources[edit]

- Lehrer, Steven (2006). Bring 'Em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-582-9.

- Rutledge Stephenson, Lynda (2015). The San Diego Zoo: The Founding Era, 1916–1953. San Diego: San Diego Zoo Global. pp. 7–12. ISBN 978-0-692-39792-3.

- Wegeforth, Harry; Morgan, Neil (1953). It Began with a Roar!: The Story of the Famous San Diego Zoo (First ed.). San Diego: Zoological Society of San Diego.

- Action in the North Atlantic. 1943.

External links[edit]

- Frank Buck at IMDb

- Frank Buck at AllMovie

- The Frank Buck Zoo

- Animal Empire collection of Frank Buck memorabilia at University of Toronto

Videos[edit]

- 1884 births

- 1950 deaths

- American radio personalities

- American male film actors

- American hunters

- Deaths from lung cancer in Texas

- Writers from Texas

- People from Gainesville, Texas

- American non-fiction children's writers

- American children's writers

- Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus

- Columbia Records artists

- American circus performers

- 20th-century American male actors

- Zoo directors

- Animal traders

- American expatriates in Singapore