Foiba

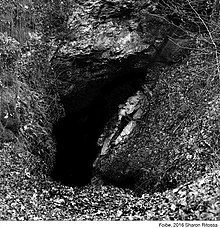

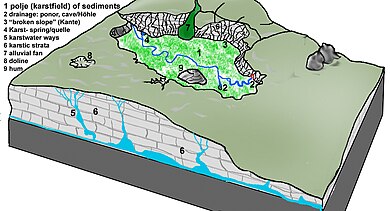

A foiba (from Italian: pronounced [ˈfɔiba]; plural: foibe ['fɔibe] or foibas) — jama (pronounced [ˈja̟mə]) in South Slavic languages scientific and colloquial vocabulary (borrowed since early research in the Western Balkan Dinaric Alpine karst) — is a type of deep natural sinkhole, doline, or sink, and is a collapsed portion of bedrock above a void. Sinks may be a sheer vertical opening into a cave or a shallow depression of many hectares. They are common in the Karst (Carso) region shared by Italy and Slovenia, as well as in a karst of Dinaric Alps in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and, Croatia. The foibe massacres, a war crime that took place during and after World War II, take their name from the foibe.

Etymology[edit]

The Italian name "foiba" derives from Friulan "foibe", which in turn derives from the Latin fŏvea (meaning "pit" or "chasm").[1][2] The oldest document on which it is reported is an official report in 1770, written by the Italian naturalist Alberto Fortis,[3] who wrote a series of books on the Dalmatian karst.

Description[edit]

They are chasms excavated by water erosion, have the shape of an inverted funnel, and can be up to 200 metres (660 ft) deep. Such formations number in the hundreds in Istria. In karst areas, a sinkhole, sink, or doline is a closed depression draining underground. It can be cylindrical, conical, bowl-shaped or dish-shaped. The diameter ranges from a few to many hundreds of metres. The name "doline" comes from dolina, the Slovenian word for this very common feature. The term "foiba" may also refer to a deep wide chasm of a river at the place where it goes underground.[4]

Foibe massacres[edit]

During and right after the end of World War II, OZNA and Yugoslav Partisans killed a number between 11,000[5][6] and 20,000[7] of the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), as well against anti-communists in general (even Croats and Slovenes), usually associated with Fascism, Nazism and collaboration with Axis,[7][5] as well as against real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism[8] by throwing their still living bodies into the foibe. This event is known as foibe massacres. The type of attack was state terrorism,[7][9] reprisal killings,[7][10] and ethnic cleansing against Italians.[7][11][12][13][14] The foibe massacres were followed by the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus.[15]

The Yugoslav partisans intended to kill whoever could oppose or compromise the future annexation of Italian territories: as a preventive purge of real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism[8] (Italian, Slovenian and Croatian anti-communists, collaborators and radical nationalists), the Yugoslav partisans exterminated the native anti-fascist autonomists — including the leadership of Italian anti-fascist partisan organizations and the leaders of Fiume's Autonomist Party, like Mario Blasich and Nevio Skull, who supported local independence from both Italy and Yugoslavia — for example in the city of Fiume, where at least 650 were killed after the entry of the Yugoslav units, without any due trial.[16][17]

In literature[edit]

Foiba is also the name of the well-known sinkhole that opens near the castle of Montecuccoli, in Pisino, and of the stream that flows into it. The place plays a central role in Jules Verne's novel Mathias Sandorf.[18]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Ottavio Lurati, Toponymie et géologie, in Quaderni di semantica, year XXIX, number 2, December 2008, 443.

- ^ "Foiba" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Hofmann, Peter (2014). Unterirdisches Istrien: Ein Exkursionsführer zu den ungewöhnlichsten Höhlen und Karsterscheinungen (in German). BoD – Books on Demand. p. 33. ISBN 978-3732298501. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "Glossary of speleology: letter F". Archived from the original on 2009-02-07. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ a b Guido Rumici (2002). Infoibati (1943-1945) (in Italian). Ugo Mursia Editore. ISBN 9788842529996.

- ^ Micol Sarfatti (11 February 2013). "Perché quasi nessuno ricorda le foibe?". huffingtonpost.it (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e Ota Konrád; Boris Barth; Jaromír Mrňka, eds. (2021). Collective Identities and Post-War Violence in Europe, 1944–48. Springer International Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 9783030783860.

- ^ a b "Relazione della Commissione storico-culturale italo-slovena - V Periodo 1941-1945". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ Il tempo e la storia: Le Foibe, Rai tv, Raoul Pupo

- ^ Lowe, Keith (2012). Savage continent. London. ISBN 9780241962220.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bloxham, Donald; Dirk Moses, Anthony (2011). "Genocide and ethnic cleansing". In Bloxham, Donald; Gerwarth, Robert (eds.). Political Violence in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 125. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511793271.004. ISBN 9781107005037.

- ^ Silvia Ferreto Clementi. "La pulizia etnica e il manuale Cubrilovic" (in Italian). Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ «....Già nello scatenarsi della prima ondata di cieca violenza in quelle terre, nell'autunno del 1943, si intrecciarono giustizialismo sommario e tumultuoso, parossismo nazionalista, rivalse sociali e un disegno di sradicamento della presenza italiana da quella che era, e cessò di essere, la Venezia Giulia. Vi fu dunque un moto di odio e di furia sanguinaria, e un disegno annessionistico slavo, che prevalse innanzitutto nel Trattato di pace del 1947, e che assunse i sinistri contorni di una "pulizia etnica". Quel che si può dire di certo è che si consumò - nel modo più evidente con la disumana ferocia delle foibe - una delle barbarie del secolo scorso.» from the official website of The Presidency of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, official speech for the celebration of "Giorno del Ricordo" Quirinal, Rome, 10 February 2007.

- ^ "Il giorno del Ricordo - Croce Rossa Italiana" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2022-01-28. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- ^ Georg G. Iggers (2007). Franz L. Fillafer; Georg G. Iggers; Q. Edward Wang (eds.). The Many Faces of Clio: cross-cultural Approaches to Historiography, Essays in Honor of Georg G. Iggers. Berghahn Books. p. 430. ISBN 9781845452704.

- ^ Società di Studi Fiumani-Roma, Hrvatski Institut za Povijest-Zagreb Le vittime di nazionalità italiana a Fiume e dintorni (1939-1947) Archived October 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali - Direzione Generale per gli Archivi, Roma 2002. ISBN 88-7125-239-X, p. 597.

- ^ "Le foibe e il confine orientale" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "La Foiba di Pisino che ispirò Jules Verne" (in Italian). 22 August 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

External links[edit]

- Gardens of the Righteous Worldwide Committee - Gariwo Archived 2012-02-20 at the Wayback Machine