Eglinton Castle

| Eglinton Castle | |

|---|---|

| Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, Scotland | |

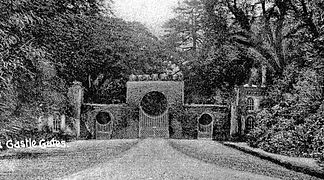

Eglinton Castle in the 1920s | |

| Coordinates | 55°38′30″N 4°40′18″W / 55.641778°N 4.671639°W |

| Height | 70 feet |

| Site information | |

| Owner | North Ayrshire Council |

| Open to the public | Eglinton Country Park |

| Condition | Stabilised Ruins |

| Site history | |

| Built | 19th century |

| Built by | 12th Earl of Eglinton |

| In use | Until the 20th century |

| Materials | Sandstone |

Eglinton Castle was a large Gothic castellated mansion in Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, Scotland.

History[edit]

The castle[edit]

The ancient seat of the Earls of Eglinton, it is located just south of the town of Kilwinning. The original Eglinton Castle was burnt by the Earl of Glencairn in 1528.[2] The current castle was built between 1797 and 1802 in Gothic castellated style dominated by a central 100-foot (30 m) large round keep and four 70-foot (21 m) outer towers, it was second only to Culzean Castle in appearance and grandeur. The foundation stone of the new Eglinton Castle in Kilwinning was laid in 1797, the 12th Earl of Eglinton, was proud to have the ceremony performed by Alexander Hamilton of Grange, grandfather of the American Hero Alexander Hamilton.[3]

Eglinton was the most notable post-Adam Georgian castle in Ayrshire.[4] Amongst many items of interest, the castle contained a chair built from the oak timbers of Alloway kirk and the back of the chair was inlaid with a brass plaque which bore the whole of Burns' poem Tam o' Shanter.[5] This was sold at an auction in 1925.[6] The previous Eglington castle (sic) was described circa 1563–1566 as a fare castell, but noo strength againsts any power.[7] An escape tunnel is said to run from the old castle to the area of the rockery on the castle lawns. The appearance of the old waterfall may have inspired this story as it looks like a sealed doorway.[8] The total acreage of the Earl of Eglinton's holdings was 34,716 Scots Acres (1 Scots acre = 1.5 English Acres) in 1788.[9] This included Little Cumbrae, and lands at Southannan and Eaglesham (Polnoon).

The original castle of Eglinton may have been near Kidsneuk, Bogside (NS 309 409) where a substantial earth mound or motte stands and excavated pottery was found tentatively dating the site to the thirteenth century.[10]

The Montgomerie's' first holdings were the Barony of Eaglesham and its Castle of Polnoon.

In 1691 the 'Hearth Tax for Ayrshire' records show 25 hearths in use, the highest number for a single dwelling in Ayrshire. It is noted that the earl had not paid the tax. The earl's house in Kilwinning, Easter Chambers or the old abbot's dwelling, had 15 hearths. Thirty-seven other dwellings were listed within the barony of Eglinton.[11]

The stables were built from stones taken from the Easter Chambers of Kilwinning Abbey; being the Abbots lodgings and later that of the Earls of Eglinton. In 1784, over a period of four months, the building was demolished and the stones were taken to Eglinton.[12]

The construction of the new castle was not universally accepted as beneficial; Fullarton records that "The hoary grandeur of the old fortalice lay deeply buried amid the dense groves of immemorial growth which closely invested and obscured it; no innovating projects of improvement, nor change of any kind, had ever been permitted to disturb the sanctity of its seclusion, or to ruffle the feelings even of the most fastiduous worshipper of things as they are, or, more properly perhaps, chance to be".[13] The castle is said to have had a moat.[14]

Covenating times[edit]

In the 1640s Alasdair Mac Colla had been sent by Montrose to suppress support for the Covenanting cause. He plundered the Ayrshire countryside for some days and then demanded financial penalties. Neil Montgomery of Lainshaw negotiated a 4,000 merks penalty for the Eglinton Estates; three tenants having already been killed, with some deer and sheep also taken from the park.[15]

Ley tunnels[edit]

Persistent rumours exist of a Ley tunnel which is said to run from Kilwinning Abbey, under the 'Bean Yaird', below the 'Easter Chaumers' and the 'Leddy firs', and then underneath the Garnock and on to Eglinton Castle. No evidence exists for it, although it may be related to the underground burial vault of the Montgomeries which does exist under the old abbey.[16] A ley or an escape tunnel is also said to run from the castle to exit at the old waterfall near the rockery. It is reported that a tunnel ran from the castle to near the existing Castle Bridge. This tunnel was stone lined and tall enough for a man to walk through. This is likely to have been the main drain from the castle.

The Pleasure gardens[edit]

Sir William Brereton in 1636 describes the landscape on his journey south from Glasgow as "a barren and poor country", but the earls had clearly enhanced Eglinton for he comments that the land at Irvine was "dainty, pleasant, level, champaign country."[17]

The grounds of the castle were described in one record of the 1840s as follows:

Its princely gates soon presented themselves and we thought we should easily find our way to Irvine through the park. It was a rich treat to wander in these extensive grounds. We soon made way through a handsome avenue to the gardens. The hot-houses for fruits and flowers are on a magnificent scale, and on reaching the parterre we were delighted with the elegance which pervaded it. A glassy river with a silvery cascade came gliding gently through these fairy regions, as though conscious of the luxuriant paradise which it was watering. Nor was the classic taste wanting, nor horticultural skill, to render this a region of enchantment. Two elegant cast-iron bridges, vases, statues, a sun-dial; these pretty combinations from the world of art could not fail to please the beholder. Leaving these luxurious regions we again wandered among thick woods, and occasionally obtained glimpses of the proud castle, peering over the trees. At length we found our way to a seat beneath some noble weepers of the ash tribe, and here we had a fine view of the castle, towering majestically over the dense foliage.

Among our wanderings we passed an enormous quadrangular building, resembling some of our London hospitals. It forms the stables, and it is quite detached, at some distance from the Castle. We mistook our way, owing to the many devious paths, and wandered deeper and deeper into the recesses of this extensive domain. In passing through one long avenue, which was so dark that we were unable to see our steps; myriads of rooks took flight at our approach, and the air was quite blackened with them. At one time, we found ourselves walking alongside of the preserves, at another we were wandering in the deer park, and startling the early slumbers of these pretty creatures. At length we reached a gate, which we fully expected would lead into the high road to Irvine: but, to our great consternation, we found it was the point from which several roads diverged, each, apparently, leading into a thick forest, and it was evident that we had much space yet to traverse ere we could be clear of the extensive grounds of Eglintoun.[18]

Service quotes a verse pertaining to the Eglinton Woods:

|

The Guid Wee Green Folk Doon by the Lugton, |

A mention in Badderley's 'Through Guide' circa 1890 indicates that the Eglinton Castle grounds were open to the public on Saturdays.[20]

Notable trees[edit]

The 'Fauna, Flora and Geology of the Clyde Area'[21] lists the notable Clyde Area trees at Eglinton in 1901, showing that the estate at the time had one of the foremost collection of significant trees in southern Scotland. Tree removal for sale as timber was one of the first acts of the new owners of the estate when it was sold in the late 1940s, however many had already been removed in 1925 by Neill of Prestwick and Howie of Dunlop, both being timber merchants.[22]

The significant trees were:- Holly (6' 10'' girth); Sycamore (13' 2'' girth – Deer Park); Field Maple (6' 5'' girth); Horse Chestnut (11' 4'' girth); Gean (girth 11' girth – Bullock Park); Hawthorn (8' 3'' girth); Fraxinus heterophylla (4' 6'' girth – Lady Jane's Cottage); Elm (12' 7'' girth – castle); Hornbeam (14' girth – between Castle & Mains); Holly Oak (5' 2'' girth – gardens); Sweet Chestnut (16' girth – Bullock Park); Beech (18' 3'' girth – Old Wood); Cut-leaved Beech (8' 11'' girth); Larch (8' 9'' girth); Cedar of Lebanon (9' 11'' girth – Bullock Park); Scots Pine (11' girth – between Castle and Mains).

The Eglinton Tournament[edit]

Eglinton is best remembered for the lavish, if ill-fated Eglinton Tournament, a medieval-style tournament organised in 1839 by the 13th Earl. The expense and extent of the preparations became news across Scotland, and the railway line was even opened in advance of its official opening to ferry guests to Eglinton. Although high summer, in typical Scottish style torrential rain washed the proceedings out, despite the participants, in full period dress, gamely attempting to participate in events such as jousting. Amongst the participants was Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (the future Emperor Napoléon III of the French).[23]

The demise of the castle[edit]

The immense cost of upkeep, the poor condition of the castle and death duties took their toll on the family finances; the castle was abandoned in 1925. De-roofed in 1926, the lead being removed and sold,[24] after a house contents sale in December 1925, and progressively ruinous, the building finally came to an undignified end during the Second World War when it was seriously damaged during army training held there. The army also partly destroyed the iron bridge running to the old walled gardens.

The 1925 house sale by Dowell's Limited, included 1,960 items auctioned, raising £7,004 19s 6d. The auction catalogue provides an interesting insight into the feelings of the family at this sad time, with much of the Montgomerie history sold off, such as the 13th Earl's suit of armour from the tournament, the panel from the door of the murdered 10th Earl's coach and many paintings of the family and the castle, including a portrait of that great beauty, Susanna Kennedy, Countess of Eglinton.[6] The family moved to Skelmorlie Castle near Largs in 1925.

Architects' drawings from March 1930 survive for plans to adapt the stable buildings as a residence for the Earl of Eglinton and Winton.[25]

Substantial remains of the castle survived WW2, however the buildings were rationalised in 1973 and only one main tower was kept, together with some outer wall, foundations and parts of the castle wings.[26]

Eglinton Castle is said by one of the gardeners to have had a room which was never opened. In about 1925 a young man from Kilwinning decided to take some of the panelling from a room in the castle as it was all being allowed to rot in the rain anyway, since the roof had been removed. He went to the castle to take away as much as he could carry, however one of the last pieces he selected left exposed the skeletal hand of a woman. The whole skeleton was later removed by a student doctor, but for fear of prosecution the matter was never reported to the police.[27]

Eglinton family micro-history[edit]

In 1583 Lady Anne Montgomerie brought her husband, Lord Semple, a dowry of 6000 merks, a considerable sum.[28]

Lady Frances Montgomerie was buried at Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh on 11 May 1797. She was the daughter of Archibald, 12th Earl of Eglinton.[29]

At the coronation of Charles I at Holyrood, the Earl of Eglinton had the honour of bearing the king's spurs.[30]

Glasgow University's Eglinton Arts Fellowship was established in 1862 by subscription to commemorate the public services of Archibald William, 13th Earl of Eglinton, Rector of the University 1852–54.[31]

At the christening of King James IV the Earl of Eglinton had the honour of carrying the salt.[32]

The potato was first heard of in Scotland in 1701; it was not popular at first. In 1733 it is however recorded as being eaten at supper by the Earl of Eglinton.[33]

Huchoun ("little Hugh") or Huchown is a poet conjectured to have been writing sometime in the 14th century. Some academics, following the Scottish antiquarian George Neilson (1858–1923), have identified him with Hugh of Eglington, and advanced his authorship of several other significant pieces of verse.

Viva Seton Montgomerie records that a gipsy put a curse on the Montgomerie family that for three generations the property would not go from father to son.[34]

The origin of the family crest is unclear, however a link may exist with the popular biblical story of an Holofernes, an Assyrian general of Nebuchadnezzar. The general laid siege to Bethulia, and the city almost surrendered. It was saved by Judith, a beautiful Hebrew widow who entered Holofernes's camp, seduced, and then beheaded Holofernes while he was drunk. She returned to Bethulia with Holofernes head, and the Hebrews subsequently defeated the enemy. Judith is considered as a symbol of liberty, virtue, and victory of the weak over the strong in a just cause.

Eglinton Country Park[edit]

In the 1970s plans were made to open the extensive grounds (988 acres) around the ruins to the public, and to that end what remained of the structure was made safe by demolishing all but a wing facade and a single tower. Eglinton Country Park is now fully established with free entry and is one of the most popular visitor attractions in Ayrshire.

Eglinton Estate was in disrepair until Robert Clement Wilson purchased the grounds and built a meat canning factory in what was the old stable block. He also restored the grounds to their former splendour at his own expense. The canning factory closed following the BSE crises in 1996.

In 1963 Ian Anstruther wrote an entertaining account of the 1839 tournament entitled The Knight and the Umbrella.

- Views of Eglinton Castle in 2007

-

The remaining tower from the Lugton Water ford side

-

The ruins from the Tournament Bridge side

-

The tower and the remaining side wall

-

The Montgomerie family crest on the castle ruins

-

Eglinton Tournament Bridge

-

The Montgomerie family crest on the offices/stables/coach house

-

The offices, coach house and old stables

The castle and estate prior to the establishment of the country park[edit]

The intact castle – exterior[edit]

-

Eglinton Castle, north side, 1811

-

Eglinton castle in 1802

-

Eglinton Castle circa 1830

-

The castle and gardens

-

Eglinton circa 1880

-

The Castle circa 1900

-

The castle circa 1870, with deer grazing in the foreground

-

Eglinton Castle in 1906

-

The castle in its prime

-

The castle from the deerpark in the 19th century

-

Eglinton castle

-

The castle in 1910[35]

-

Eglinton Castle bridge in 1811

-

The castle and bridge. Three arches and a lake are illustrated.

William Aiton relates in 1811 that near the end of each June each year the Earl of Eglinton held three days of races at Bogside, following which he always gave a grand ball and supper at Eglinton Castle.[36]

-

Eglinton castle and bridge. This shows three arches and other differences compared with the surviving bridge.[37]

-

The castle and bridge in 1884

-

The Tournament Bridge and castle in 1876

-

The Tournament Bridge over the Lugton Water in 2007

-

The procession crossing the Tournament Bridge in 1839

-

The old Game Larders

-

A livery button from a servant's uniform

-

Eglinton Kennels and the hunt

-

The Eglinton Hunt outside the castle

The castle interior[edit]

-

The Inner Hall circa 1860

-

An interior view from the 1860s

-

The library and the Eglinton Trophy

-

An interior view of the castle, circa 1860

-

An interior view of the castle's central tower, circa 1860

-

An interior view

Castle ruins[edit]

-

The castle ruins in the 1950s

-

The ruins of Eglinton castle in 1965

-

Detail of the castle ruins

-

Castle ruins and driveway in 1965

Estate features[edit]

Lady Susanna's Cottage[edit]

Lady Susanna Montgomerie, wife of the 9th Earl of Eglinton, was a renowned society beauty and her husband built for her at Kidsneuk a copy of the Hameau de la Reine 'cottage orné' that Marie Antoinette had famously possessed at Versailles. This building, now a golf clubhouse, was thatched until the 1920s and is built of whin with steeply pitched roof sections and many gables.[38]

Dower houses[edit]

The tradition was that a dowager countess would move out of the Earl's ancestral seat and move to a lesser dwelling. The Lady Susanna, wife of the 9th Earl, moved to Kilmaurs House and then to Auchans Castle for instance. Over the centuries Seagate Castle, the Garden or Easter Chambers in Kilwinning,[39] Kilmaurs House, Auchans Castle and Redburn House were some of the dower houses used.

The Rackets Hall[edit]

Eglinton has a 'Racket Hall' which was built shortly after 1839, the first recorded match being in 1846. The court floor is of large granite slabs, now hidden by the wooden floor. It is the very first covered racquet court, built before the court size was standardised and is now the oldest surviving court in the World, as well as being the oldest indoor sports building in Scotland.[40] In 1860 the earl employed a rackets professional, John Mitchell and Patrick Devitt replaced him. Mitchell owned a pub in Bristol with its own rackets court and this was named the "Eglinton Arms", having been the "Sea Horse" previously.[41]

Captain Moreton's Eglinton Castle croquet[edit]

A croquet lawn existed on the northern terrace, between the castle and the Lugton Water, also the old site of the marquee for the tournament banquet. The 13th Earl developed a variation on croquet named 'Captain Moreton's Eglinton Castle Croquet', which had small bells on the hoops 'to ring the changes' and two tunnels for the ball to pass through. Several incomplete sets of this form of croquet are known to exist. It is not known why the earl named it thus.[42]

Lady Ha'[edit]

The Montgomerie family are said to have had a pre-reformation chapel in the Weirston - Lady Ha' area dedicated to Saint Issyn. A 'Ladiehall' dwelling still existed in 1691, occupied by John and James Weir. Two other 'Weir' families also lived on the estate.[11]

- Views of the estate

-

Stanecastle gate circa 1860

-

Redburn Gate circa 1903

-

Redburn gate circa 1910

-

Nannies with a donkey cart at the Redburn Gate

-

Redburn Gate

-

Unusual masonry at the Stanecastle Gate

-

Long Drive near Stanecastle Gate in 2009

-

Lady Jane's cottage ornee. A ruin by 1928.[24]

-

Lady Jane's cottage in the snow. Circa 1904

-

A later view of the cottage

-

Lady Jane's in the 1880s (hand-tinted photograph)

-

The Lugton Water and one of the two gazebos

In 1811 Aiton records that Galloway Cattle were kept at Eglinton and one stot yielded 52 stones of beef and 14.5 stones of tallow in Ayrshire weights, being 78 stones and 21.75 stones in English weights.[43]

-

The Lugton in the snows. Circa 1906.

-

The Pleasure Gardens from one of the castle towers

-

The Tournament Bridge in the 1960s

-

The tennis court in the 1920s

-

Croquet on the North Terrace in the 1890s

-

The old estate offices and stables

-

A view from the south of the estate offices and stables

-

Gothic cross on the doocot.

Oddly the Eglinton coat of arms restored and displayed in the Stables Courtyard have the armorial bearings as a mirror image of the standard Eglinton representation.

-

Curling at the Eglinton Flushes in 1860

-

Practice in the nets at Eglinton circa 1890

-

Weirston House, home of the estate factor

-

Coat of Arms from the 1790s Eglinton Castle.

-

1790s Coat of arms restored

-

The Eglinton Loft in the Abbey church.

The people of the estate[edit]

In the early 1900s the records show that Mr Priest was the Head Gardener, Mr Muir the Head Groom, Mr Brooks the Coachman, Mr Pirie the Gamekeeper, and Mr Robert Burns was the estate blacksmith.[25]

-

The Earl and Countess of Eglinton at the races

-

H.S.M. Young, the Eglinton Estate Factor.

-

Factor Young. His salary was £300 a year in 1929.

-

Mr. Young at Weirston in the year of his retirement - 1935.

-

Commissioner Vernon, Eglinton estates.

-

David Mure's memorial. He was the Earl's Chamberlain.

Derelict estate features[edit]

-

The courtyard undergoing initial restoration

-

The old stables prior to conversion into the Tournament cafe

-

The stables prior to redevelopment into the visitor centre

-

The doocot prior to restoration – Stanecastle facing end. The council had kept vehicles in it.

-

The doocot – the Kilwinning facing end

-

Stanecastle gate 1965

-

A stone with recessed markings from the ornate footbridge.

-

The ruins of one of the two listed gazebos

-

Ruins of the gazebo or temple by the Lugton wear or cascade

-

The interior of the gazebo by the wear

A single span iron bridge once crossed the Lugton Water at the kitchen or walled garden. This bridge was removed at some time after WWII and only the ornate vermiculate ashlar masonry abutments survive.

-

A part of the kitchen garden wall

-

The old Wilson's waterfall – upper area

-

The old Wilson's waterfall.

-

The Diamond Bridge undergoing restoration

-

The old curling ponds off Weirstone Drive

-

Another view of the old curling ponds

The 1930s bridge collapse and repair work[edit]

-

A view across the damaged bridge

-

A view showing the partial collapse of the bridge

-

The bridge with temporary supports

-

Repair work underway, showing the shuttering for the concrete

-

The repaired bridge. Note the simple wooden handrail and the remaining exposed iron arch.

-

A view of the whole of the repaired bridge. Note the army personnel, children fishing, etc.

The Earls of Eglinton[edit]

-

Hugh Montgomerie 12th Earl of Eglinton circa 1780 Oil on canvas by John Singleton Copley

-

A statue to the 13th Earl in Wellington Square gardens, Ayr

-

The 15th Earl of Eglinton at Eglinton Castle

-

The 16th Earl, Archibald William

-

Lord Montgomerie (17th Earl) in 1921 from a painting presented by the tenantry of Eglinton estates

-

The Lord of the Tournament (Earl of Eglinton) and his esquires and retainers crossing the bridge[44]

-

A panel from the coach in which the 10th Earl travelled during the Mungo Campbell incident. Sold at the auction in 1925.

-

Outside facing portion of the 1769 carriage panel

-

The Montgomerie family mausoleum at Kilwinning cemetery

-

The signature of the Earl of Eglinton in 1642

-

The Montgomerie family crest. An anchor is often used as a symbol for 'hope' or 'fresh start'.

-

Bronwen Peers-Williams (wife of the Hon Seton Montgomerie) and her sisters.

Estate microhistory[edit]

Lady Egidia[edit]

The "Egidia" was one of the largest, if not the largest wooden vessels ever built in Scotland. She measured 219 feet long, extreme breadth 37 feet, depth 22 feet, registered tonnage 1,235, builders measurements 1,461 tons. Lady Egidia was the daughter of the Earl of Eglinton. The Earl launched her at Ardrossan in 1860.[45]

The Pavilion[edit]

In the early 1900s, the Earl of Eglinton and Winton had a summer residence called the Pavilion at 1 South Crescent Road, Ardrossan. It was built at the beginning of the previous century. In the 1920s the Pavilion, two lodges, stables and walled garden in 3.4 acres of ground were sold to the Roman Catholic Church on 30 January 1924 for £4500. The pavilion was demolished and the present day church and manse built on the site.[46]

White or Chillingham Cattle[edit]

In 1759 the Earl of Eglinton formed a herd of the ancient breed of White or Chillingham Cattle at Ardrossan, probably using stock from the Cadzow herd. The numbers dropped and in 1820 the remaining animals were dispersed. All the animals in this herd were hornless.[47]

The Garden or Easter Chambers[edit]

After the destruction of the main buildings at Kilwinning Abbey the Garden or Easter Chambers within the boundary walls of the old abbey, previously the dwelling of the abbot were used by the new owners, the Earls of Eglinton, as a dower house and family dwelling. Lady Mary Montgomerie lived here after the death of her husband in the 17th century and her son may have remained here until he succeeded to the Earldom. The building, which stood to the south of the abbey, was eventually demolished in 1784 and the stones used in building projects at the castle, particularly the stable offices.[39] The 1691 Hearth Tax records show that this substantial building had 15 hearths.[11]

Daft Will Speirs[edit]

A well known Ayrshire eccentric, Will had been a high spirited youth, punished by being hung over the edge of a bridge over the River Garnock whilst it was in flood, resulting in a form of nervous breakdown which left him as a likeable character, accepted by most and a regular visitor to many a laird or earl's estates. Will died at Corsehillmuir whilst going from Bannoch to Moncur, falling into an old mine shaft whilst trying to rescue a collie dog.[48]

The Buffalo Park[edit]

An area below the old Mains Farm was known as the 'Buffalo Park' and this may relate to the 11th Earl having been involved in the British army's subjugation of the Cherokee Indians in North America.[24]

The Irish Giant[edit]

John Service relates an Ayrshire legend that an Irish Giant came to mock the warlock Laird of Auchenskeith who lived near Dalry and the laird chased him across to Eglinton where the giant went to crush him with a great beech tree. The laird pierced him through the arm bones with his sword and the giants hand remained attached to the tree for centuries. It could be seen from a distance of about a mile - from Kilwinning, between Dykehead and the Redburn.[49]

Vagrants and the unemployed[edit]

In 1662 the Earl was given the rights to the manual labour of all the vagrants and temporarily unemployed in Renfrewshire, Ayrshire and Galloway. These individuals were taken to Montgomerieston at the Citadel of Ayr where the Earl had a wool factory. The parishes had to support them whilst there and the Earl only had to provide food and clothing. The rights lasted for 15 years for the vagrants and five years for the unemployed.[50]

The National Covenant[edit]

A painting by W. Hole RSA of the 1638 Signing of the National Covenant in Greyfriars Churchyard features the Earl of Eglinton in the crowd, just prior to his putting his signature to the document.

Lady Jane's Cottage[edit]

A similar style of cottage existed at Kidsneuk and on the Fullarton estate in Troon as a lodge house near the Crosbie Kirk ruins.[51] Lilliput Lane has produced a model of Lady Jane's cottage.[52] An ash of the species Fraxinus heterophylla of 4' 6'' girth – once grew at Lady Jane's Cottage.

Cigarette Cards[edit]

The castle and bridge were featured in the series on castles, abbeys and houses by Salmon & Gluckstein Ltd.

Annick School[edit]

The Earl of Eglinton built a large schoolroom and a house for the teacher at Annick near Doura; he also provided a garden and a playground.[53] The building ceased to be a school and was used as a cafe for a few years before being adapted to become private accommodation.

Hare Coursing[edit]

The Ardrossan Hare Coursing Club used to pursue hares on Ardrossan Hill in the 1840s and would then return to Eglinton Castle for refreshments provided by the 13th Earl. This bloodsport finally became illegal in Scotland in 2002. A famous greyhound owned by Lord Eglinton was named 'Heather Jock' after a colourful local character of that name.

Religion[edit]

In the 1622 persecution the minister of Irvine, Mr David Duckson, was banished, however the earl had him returned to his charge. Anne, Countess of Eglinton, daughter of Alexander Livingstone, 1st Earl of Linlithgow, was very religious, and Eglinton was a safe haven for persecuted ministers. She took an interest in the Stewarton Revival and invited some of the adherents to meet the earl and the castle.[54]

In the nineteenth century the Montgomerie's of Eglinton were supporters of the Scottish Episcopalian church and the Rev W. S. Wilson travelled to the castle on Sunday afternoons to conduct services. The earl granted a piece of land in Ardrossan with a nominal feu duty to the church and his countess laid the church foundation stone on 30 November 1874; it opened in 1875 and consecrated in 1882 by Bishop Wilson.[55]

Farms[edit]

Aiton in 1811 records that nearly all the farms on the extensive estates of the 10th Earl of Eglinton were elegant, commodious, and substantial.[56]

Montgomerystown[edit]

Ayr citadel, later called the Fort, was constructed by Oliver Cromwell in 1652 with stones taken from the Earl's castle at Ardrossan. It occupied an area of about 12 acres, on a hexagonal ground plan, with bastions at the angles, and enclosed the church of St John the Baptist, converted by Cromwell into an armoury and guard-room. After Cromwell's time it was dismantled and the ground it occupied, together with its buildings, presented to the Earl of Eglinton as compensation for losses sustained during the Great Rebellion. Renamed Montgomerystown, it was created a burgh of regality, and became the seat of a considerable trade, including a family owned brewery. In 1726 it was purchased by four merchants from the town, and c. 1870, most of it covered with high quality housing.[57]

Early automobile accident[edit]

In 1911, a motor van belonging to the American Steam Laundry Company, Kilmarnock, while proceeding along the country road between Burnhouse and East Middleton on its way towards Lugton, through the steering gear going wrong, was overturned in a ditch. All 4 occupants were thrown out and two of them were seriously injured. Lord Eglinton was passing in his car at the time and had the injured parties taken to Beith in his car. The injured parties were treated for head and body injuries after which they were driven to Lugton and entrained for Kilmarnock.[58]

Rozelle[edit]

Archibald Hamilton, a younger son of John Hamilton of Sundrum, married Lady Jane Montgomerie of Coilsfield (his cousin), daughter of the 12th Earl of Eglinton and doting aunt to the 13th Earl of Eglinton. The 13th earl gave the couple a life-rent interest in the mansion house of Rozelle. The estate of Rozelle (formerly Rosel) had been part of the lands of the Barony of Alloway. The future estate was purchased by Robert Hamilton of Bourtreehill, his uncle, a former Jamaica merchant who named it after a Jamaican property and also built the mansion house (1760). Archibald Hamilton rebuilt the house in the 1830s to designs by the architect David Bryce and in 1837 he purchased the Rozelle estate.[59]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ Dobie, James (1876). Pont's Cuninghame Pub. John Tweed.

- ^ Way, George and Squire, Romily. (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia, pp. 278 - 279.

- ^ Kilwinning Heritage

- ^ Sanderson, Maragaret H. B. (1993), Robert Adam in Ayrshire. Ayr Arch Nat Hist Soc. Monograph No. 11. p. 18.

- ^ Aikman, J. & Gordon, W. (1839) An Account of the Tournament at Eglinton. Pub. Hugh Paton, Carver & Gilder. Edinburgh. M.DCCC.XXXIX.

- ^ a b Dowells Ltd. Catalogue of the Superior Furnishings, French Furniture, etc. Tuesday, 1 December 1925, and four following days.

- ^ Military Report on the Districts of Carrick, Kyle & Cunningham. Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to Ayr & Wigton. 1884. Vol. IV. Pub. Ayr & Wigton Arch Assoc. p. 23.

- ^ Barr, Allison (2008), Five Roads / Corsehillhead resident.

- ^ National Archives of Scotland. RHP35796/1-5.

- ^ Simpson, Anne Turner and Stevenson, Sylvia (1980), Historic Irvine the archaeological implications of development. Scottish Burgh Survey. Dept. Archaeology, Univ Glasgow. p. 23.

- ^ a b c Urquhart, Page 92

- ^ Service, Page 140

- ^ Fullarton, Page 85

- ^ Anstruther, Page 27

- ^ Stevenson, David (1994). Highland Warrior. Alasdair MacColla and the Civil Wars. Edinburgh: The Saltire Society. ISBN 0-85411-059-3. p. 205.

- ^ Service, page 48.

- ^ Brereton

- ^ Phipps, pages 61–63.

- ^ Service, Page 181

- ^ Newsletter (1989), Page 8

- ^ Scott Elliot, G. F., Laurie, M. and Murdoch, J. B. (1901). Glasgow: British Association. pages 131–147.

- ^ Eglinton Archives, Eglinton Country Park.

- ^ Ker, Page 318

- ^ a b c Eglinton Archive, Eglinton Country Park

- ^ a b Eglinton Archive

- ^ Campbell, Page 177

- ^ Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 98.

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1885). Domestic Annals of Scotland. Edinburgh: W & R Chambers. p. 236.

- ^ Daniel, page 199.

- ^ Daniel, page 111.

- ^ Glasgow University Art's Fellowship. Archived 2006-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1885). Domestic Annals of Scotland. Edinburgh: W & R Chambers.

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1885). Domestic Annals of Scotland. Edinburgh: W & R Chambers. p. 404.

- ^ Montgomerie, Page 2

- ^ Harvey, William (1910), Picturesque Ayrshire. Pub. Valentine & sons, Dundee, etc. Facing p. 110.

- ^ Aiton, Page 575

- ^ Leighton, John M. (1850). Strath Clutha or the Beauties of the Clyde. Pub. Joseph Swan Engraver. Glasgow. Facing p. 229.

- ^ Close (2012), Page 391

- ^ a b Fullarton, Page 21

- ^ Eglinton Country Park archive

- ^ Ashford, P. K. (1994). Eglinton Archive, Eglinton Country Park

- ^ Eglinton Archive, Eglinton Country Park - falconer

- ^ Aiton, William (1811). General View of The Agriculture of the County of Ayr; observations on the means of its improvement; drawn up for the consideration of the Board of Agriculture, and Internal Improvements, with Beautiful Engravings. Glasgow. p. 418

- ^ The Eglinton Tournament. London: Hodgson & Graves. 1840. p. 6.

- ^ The Ships List Archived 2011-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2011-07-03

- ^ St Peter in Chains Retrieved: 2010-11-18

- ^ Turner, Page 239

- ^ Service, Pages 42 - 43

- ^ Service, page 105

- ^ Lauchland, Page 27

- ^ Heather House, Troon. Accessed: 2009-12-11

- ^ Lilliput Lane - Scottish models. Accessed: 2009-12-11

- ^ Shaw, Page 27

- ^ Buchan, Page 19

- ^ Shaw, 128

- ^ Aiton, Page 118

- ^ Gazetteer for Scotland Retrieved: 2011-02-18

- ^ Early automobile accident Archived 2010-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SCRAN Archived 2011-10-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 2011-08-21

- Sources

- Aiton, William (1811). General View of The Agriculture of the County of Ayr; observations on the means of its improvement; drawn up for the consideration of the Board of Agriculture, and Internal Improvements, with Beautiful Engravings. Glasgow.

- Anstruther, Ian (1986). The Knight and the Umbrella. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-302-4.

- Brereton, Sir William. Travels in Holland, The United Provinces, England, Scotland, and Ireland. edit. Edward Hawkins, The Chetham Society 1844.

- Buchan, Peter (1840). The Eglinton Tournament and Gentlemen Unmasked. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0.

- Clan Montgomery Society of North America. Newsletter. Summer 1989. V. IX. No. 2.

- Close, Rob and Riches, Anne (2012). Ayrshire and Arran, The Buildings of Scotland. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14170-2.

- Fullarton, John (1864). Historical Memoir of the family of Eglinton and Winton. Ardrossan: Arthur Guthrie.

- Ker, Rev William Lee (1900). Kilwinning. Kilwinning: A. W. Cross.

- Lauchland, John (2000). A History of Kilbirnie Auld Kirk. The Friends of the Auld Kirk Heritage Group.

- Montgomerie, Viva Seton (1954). My Scrapbook of Memories. Privately produced.

- Phipps, Elvira Anna (1841). Memorials of Clutha or Pencillings on the Clyde. London: C. Armand.

- Service, John (1913). The Memorables of Robin Cummell. Paisley: Alexander Gardner.

- Service, John (1890). Thir Notandums, being the literary recreations of the Laird Canticarl of Mongrynen. Edinburgh: Y. J. Pentland.

- Shaw, James Edward (1953). Ayrshire 1745-1950. A Social and Industrial History of the County. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd.

- Swinney, Sarah Abigail (2009). Knights of the quill: The Arts of the Eglinton Tournament. Texas: Baylor University.

- Turner, Robert (1889). The Cadzow Herd of White Cattle. Proceedings and Transactions of the Natural History Society of Glasgow. V.2.

- Urquhart, Robert H. et al. (1998). The Hearth Tax for Ayrshire 1691. Ayrshire Records Series V.1. Ayr: Ayr Fed Hist Soc ISBN 0-9532055-0-9.

External links[edit]

- Video and commentary on the Rackets Hall.

- Video and commentary on the Earls racecourse at Bogside.

- Video and commentary on the Tournament Bridge.

- Commentary and video of Seagate Castle, Irvine.

- SCRAN site with photographs.

- Winton Estate. Earls of Winton.

- A Narrated YouTube video on Lady Jane's Cottage.

- A Model of Lady Jane's Cottage on YouTube.

- Video & commentary on Auchans House and Lady Susanna Montgomerie

- Commentary and video on the Eglinton Dovecote.

- Commentary and video on the Eglinton Ice House.

- Houses in North Ayrshire

- Castles in North Ayrshire

- History of North Ayrshire

- Landscape design history

- Architectural history

- Gothic Revival architecture in Scotland

- Category C listed buildings in North Ayrshire

- Listed castles in Scotland

- Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes

- Demolished buildings and structures in Scotland

- Kilwinning

- Clan Montgomery

![The castle in 1910[35]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/Eglinton_castle_1910.jpg/340px-Eglinton_castle_1910.jpg)

![Eglinton castle and bridge. This shows three arches and other differences compared with the surviving bridge.[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Eglinton_tournament_bridge_in_1843.jpg/329px-Eglinton_tournament_bridge_in_1843.jpg)

![Lady Jane's cottage ornee. A ruin by 1928.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/7/75/Eglinton_Lady_Jane%27s_cottage.jpg/229px-Eglinton_Lady_Jane%27s_cottage.jpg)

![The Lord of the Tournament (Earl of Eglinton) and his esquires and retainers crossing the bridge[44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Lord_of_the_Tournament_%26_his_esquires_%26_retainers.JPG/241px-Lord_of_the_Tournament_%26_his_esquires_%26_retainers.JPG)